ELIJAH F. TEMPLE vs. FRED E. BENSON.

ELIJAH F. TEMPLE vs. FRED E. BENSON.

When on the face of a deed of land no uncertainty is disclosed as to the monuments or boundaries described, but the description is shown to be ambiguous when it is applied on the land to the monuments referred to, extrinsic evidence is admissible to show what boundaries the language of the deed was intended to describe.

PETITION, filed in the Land Court on September 8, 1910, for the registration of the title to certain land on East Quincy Street in North Adams.

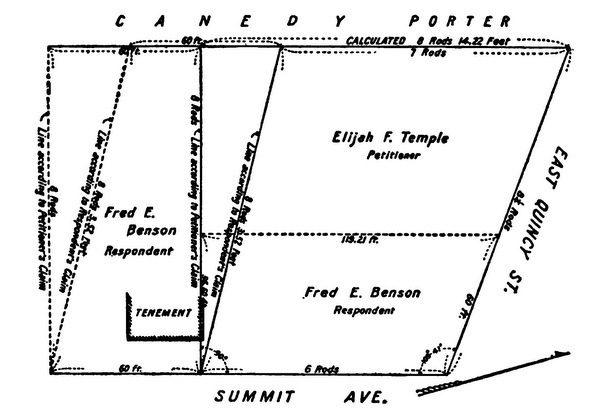

In the Land Court the case was heard by Davis, J. The only issue at the trial was the position of the southerly line of the petitioner's land as shown on the sketch on the next page.

In 1870 one Sylvester A. Kemp owned land which included the locus and land immediately east and south of it shown on the plan as land of the respondent, and conveyed to one Josiah Tinney the locus and the lot east of it by a deed with the following description: "Situate near the North Village of North Adams, bounded and described as follows, to wit: Commencing on the south side of East Quincy Street, so called, at the point of its intersection with Mechanic Street (now Summit Avenue), so called; thence south 12 degrees west on the west side of a contemplated street, six rods to a stake and stones; thence westerly eight rods to land of J. M. Canedy; thence northerly on lands of J. M. Canedy and

Page 129

Mrs. Porter seven rods to East Quincy Street; thence easterly on the south side of said street, about eight and one-fourth rods, to the place of beginning."

The same premises were conveyed by four mesne conveyances to one Samuel Vadner, who received them in 1885, all the deeds containing the same description as that given above.

In 1887 Kemp conveyed to the respondent land south of that previously described, by a deed containing the following description:

"Beginning on the west side of Summit Avenue, at the southeast corner of land of Samuel Vadner, running westerly on the south line of said Vadner's land, eight rods to land of Charles Tower (formerly of J. M. Canedy); thence southerly on said Tower's land, sixty feet; thence easterly eight rods to Summit Avenue; thence northerly on the west side of Summit Avenue, sixty feet to the place of beginning."

On June 1, 1890, Vadner conveyed to the respondent the lot east of the locus by a deed with the following description: "Commencing at the northeast corner of lands of said Benson, on the west side of Summit Avenue; thence running northerly on the west line of Summit Avenue, about six rods to East Quincy Street;

Page 130

thence westerly on East Quincy Street, sixty feet to stake and stones; thence southerly on line parallel with the first mentioned line, about six rods, to land of said grantee; thence easterly on land of said Benson, sixty feet to place of beginning."

In 1894 Vadner conveyed the locus to the petitioner by a deed containing the following description: "Beginning on the south side of East Quincy Street, so called, at a point of its intersection with Mechanic Street (now Summit Avenue), so called; thence south twelve degrees west, on the west side of a contemplated street, six rods to a stake and stones; thence westerly eight rods, to land formerly owned by J. M. Canedy; thence northerly on said land and land of Mrs. Porter, seven rods to said East Quincy Street; thence easterly on the south side of said street, about eight and one-fourth rods to place of beginning, except what I have sold pertaining to this lot of land to Fred E. Benson, of said North Adams, with deed dated June 1st, 1890."

In 1870 neither East Quincy Street nor Summit Avenue was a public street. Kemp had opened East Quincy Street as a private way. After 1879 both streets were public streets, East Quincy Street being two rods wide. The bill of exceptions states: "The point of intersection of East Quincy Street, and Mechanic Street, or Summit Avenue, in July, 1870, was agreed to as the point marked on the annexed sketch, at the northeast corner of the lot at the intersection of East Quincy Street and Mechanic Street and has never been changed and is the point of intersection of the south line of East Quincy Street and west line of Summit Avenue, as laid out by the City of North Adams, in 1879."

The westerly boundary line of the locus was fixed by a stone wall which was parallel to Summit Avenue.

The petitioner contended that the southerly line of East Quincy Street as laid out by North Adams was in a different location from the southerly line of East Quincy Street as it was understood to be before that time. The respondent contended that that line had not been changed. Both parties offered evidence in support of their contentions.

The judge ruled as follows, subject to an exception by the respondent: "The description in the petitioner's deed cannot as a physical matter be literally applied in all its details to the ground. If the westerly end of the southerly line be taken as contended for

Page 131

by the respondent at a point on the Canedy land distant exactly seven rods from the southerly line of East Quincy Street, then the southerly line will exceed eight rods in length. If on the other hand the westerly end of said southerly line be taken at a point on the Canedy land distant exactly eight rods from its point of departure, on the westerly line of Summit Avenue, then the westerly line on land of Canedy and Porter will exceed seven rods in length. ... I rule that the deed is ambiguous."

Subject to an exception by the respondent, the judge admitted in evidence, "so far as it tended to show the location of East Quincy Street," a deed by Kemp to one Frost dated in 1872. According to the description in the deed, the north line of East Quincy Street extended over the east side of Summit Avenue and ran south 79º east, and the street was three rods wide through the land of Porter.

Subject to a further exception by the respondent, the judge allowed Tinney, called by the petitioner, to testify "that at the time he bought his land, previously described, from Kemp and before the deed was drawn, he went on the ground with Kemp; that they began at the northeast corner of the lot he was to buy, at the corner of Summit Avenue and East Quincy Street, and measured south on Summit Avenue, six rods; that from there they turned a right angle, because Kemp stated he wanted 'to measure at right angles so that all the lots would come square,' and measured eight rods to the old stone wall on Canedy land; that they then measured down the line of Canedy land seven rods and stopped there, in order, Kemp said, to leave room for a street, Kemp stating he might throw the street to the north or to the south, and that he would deed by the street so that if the street went to the north Tinney would be the gainer; that the measurements stopped about one rod short of the nearest wheel track, and that two or three days later the deed was drawn, executed and delivered." The judge found for the petitioner; and the respondent alleged exceptions.

The case was submitted on briefs.

M. E. Couch, for the respondent.

J. F. Noxon & M. Eisner, for the petitioner.

BRALEY, J. The petitioner by mesne conveyances and the

Page 132

respondent by direct grant derive title to their respective lands which are contiguous on the south from a common grantor Sylvester A. Kemp, and as the duly recorded deed from him to Joseph Tinney under whom the petitioner claims, antedates his deed to the respondent, it follows upon comparison of the descriptions, that when the position of the disputed southerly line of the petitioner's lot has been ascertained the northerly line of the respondent's lot also will have been defined, and the controversy determined.

It is a familiar rule in the construction of deeds, that, where the land conveyed is described by courses and distances and also by monuments which are certain or capable of being made certain, the monuments govern, and the measurements if they do not correspond must yield. Howe v. Bass, 2 Mass. 380. Pernam v. Wead, 6 Mass. 131. Mann v. Dunham, 5 Gray 511, 514. George v. Wood, 7 Allen 14. Morse v. Rogers, 118 Mass. 572, 578. Percival v. Chase, 182 Mass. 371. In its application natural or permanent objects, such as streams or rivers and the shore of the sea, or highways or other lands, or artificial land marks or signs such as fences, walls, a line, a building, or a stake and stones, are to be treated as monuments or boundaries. Storer v. Freeman, 6 Mass. 435. King v. King, 7 Mass. 496. Flagg v. Thurston, 13 Pick. 145. Whitman v. Boston & Maine Railroad, 3 Allen 133. Paine v. Woods, 108 Mass. 160. Boston v. Richardson, 13 Allen 146. Needham v. Judson, 101 Mass. 155. Pernam v. Wead, 6 Mass. 131. Smith v. Smith, 110 Mass. 302. Charlestown v. Tufts, 111 Mass. 348. Frost v. Angier, 127 Mass. 212. And their identity may be established by extrinsic evidence. White v. Bliss, 8 Cush. 510, 512. The only exception recognized is, where, by strict adherence to monuments, the construction is plainly inconsistent with the intention of the parties as expressed by all the terms of the grant. Davis v. Rainsford, 17 Mass. 207. Murdock v. Chapman, 9 Gray 156. George v. Wood, 7 Allen 14.

The petitioner had the burden of proving himself entitled to registration of the premises as described in the application. Bigelow Carpet Co. v. Wiggin, 209 Mass. 542.

On the face of the deed no uncertainty as to the distances or the location of the monuments or boundaries is disclosed, yet upon applying the description to the land it became apparent that the

Page 133

southerly line must run at a right angle westerly from the stakes and stones in the west side of Summit Avenue "to land formerly owned by J. M. Canedy" or the call for a distance of eight rods cannot be satisfied. But if, as claimed by the respondent, this line should run from the stake and stones to the Canedy land, the abuttal or boundary on the west, at a point distant seven rods from the south side of East Quincy Street, the boundary on the north, it would exceed eight rods, and the area of the petitioner's land called for by his deed would fall correspondingly short, as is clearly shown by the first sketch or plan forming part of the exceptions.

The parties agreed that, as marked on the plan, the starting point of the lot was the northeast corner at the intersection of East Quincy Street with Summit Avenue, which never had been changed, and the respondent's exception to the admission of the deed of Kemp to Pattie D. Frost would seem to have become immaterial. It was, however, properly admitted. At the date of the deed to Frost East Quincy Street, although a private way opened by the grantor was a boundary common to the land conveyed to her as well as to the tract, a part of which was later deeded to the respondent, and grants of adjacent premises even between strangers are admissible where the location of the land for which registration is sought is in dispute. Sparhawk v. Bullard, 1 Met. 95, 100. Devine v. Wyman, 131 Mass. 73.

The northerly boundary and point of beginning being certain, the easterly boundary was the west side of the avenue, measuring six rods to a stake and stones. The termini and length of the first course were thus fixed, and the stake and stones from which the second or southerly course starts locates and controls the easterly end. No further description is given, and the presumption is that this course, whatever the interior angle may be, ran straight to the land on the west, although it could not be deflected by parol evidence to a point north of the Canedy land. Allen v. Kingsbury, 16 Pick. 235. Jenks v. Morgan, 6 Gray 448. Hovey v. Sawyer, 5 Allen 554, 555. Henshaw v. Mullen, 121 Mass. 143. The angle of departure however is not given, and, as the southerly line claimed by each party is not irregular, but when projected extended directly from landmark to landmark, a material discrepancy in the measurement of the third or westerly course

Page 134

would be caused whichever position is taken. A latent ambiguity, as the judge properly ruled, had been developed which could be removed only by proof of extrinsic facts. Frost v. Spaulding, 19 Pick. 445. Stone v. Clark, 1 Met. 378. Stevenson v. Erskine, 99 Mass. 367. Miles v. Barrows, 122 Mass. 579. Graves v. Broughton, 185 Mass. 174. Haskell v. Friend, 196 Mass. 198. Weeks v. Brooks, 205 Mass. 458, 462, 463. Compare Hall v. Eaton, 139 Mass. 217.

It appears from the chain of title that Kemp, when the owner of the entire tract shown by the plan, first conveyed the portion lying northerly of the respondent's land to Joseph Tinney, and the declarations of Kemp to Tinney made while measuring the land, and contemporaneous with the giving of the deed, "that from there," meaning the stake and stones, "they turned a right angle because Kemp stated he wanted to measure at right angles so that all the lots would come square, and measured eight rods to the old stone wall on the Canedy land," was clearly admissible. Abbott v. Walker, 204 Mass. 71, 73. Blake v. Everett, 1 Allen 248. Davis v. Sherman, 7 Gray 291. The subsequent conveyance of Kemp to the respondent also shows a rectangular lot, and the description is confirmatory of the grantor's previously expressed purpose in fixing the shape of the lots, that the respondent's northerly line should run at a right angle with the westerly side of Summit Avenue, and not at an acute angle as the respondent contends.

The adverse finding of fact of which the respondent complains, that the southerly line should be established as contended for by the petitioner, having been warranted by the evidence, is conclusive, and the decision that the petitioner had the right to have his title confirmed and registered as described in the application shows no error of law. American Malting Co. v. Souther Brewing Co. 194 Mass. 89. R. L. c. 128, § 37.

Exceptions overruled.