SAMUEL H. WALDSTEIN vs. PHILIP DOOSKIN & another.

SAMUEL H. WALDSTEIN vs. PHILIP DOOSKIN & another.

Evidence, Extrinsic affecting writing. Contract, In writing.

The position on the paper of words written in an order for goods may create such an ambiguity as to render oral evidence admissible to explain the meaning of the instrument.

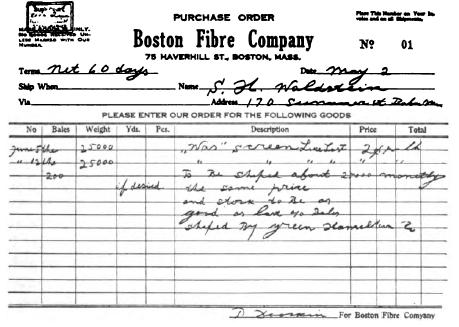

At the trial of an action by one broker against another for an alleged breach of a contract to receive and pay for cotton waste, it appeared that, after a telephone conversation between the parties relating to the sale of the waste by the plaintiff to the defendant, the plaintiff wrote to the defendant a letter purporting to confirm the contract, and the defendant for the same purpose delivered to the plaintiff a purchase order signed by him containing three items, each occupying a line. The first two items were for twenty-five thousand pounds of waste at a specified price. Under them at the left side of the paper was an item of two hundred bales, and opposite it at the right side of the paper were the words "To Be shiped about 25000 monetly." On the next line of the order and near the middle of the paper, standing alone, were the words "if desired." On the same line with them and under the words, above described, at the right side of the paper were other words descriptive of price and quality. Held, without deciding that the plaintiff's letter and the defendant's order constituted a contract between the parties, that it could not be ruled as a matter of law that the words "if desired" related only to the time of shipment, and that there was enough of doubt and uncertainty as to their meaning to warrant the admission of evidence to explain them and to require the submission of the question of their meaning to the jury.

CONTRACT for the alleged breach of an agreement by the defendants to accept and pay for two hundred bales of cotton waste, called "WAS cotton waste." Writ dated December 29, 1911.

In the Superior Court the case was tried before Bell, J. There was evidence that the plaintiff and the defendants were brokers, that the plaintiff and the defendant Dooskin had a telephone conversation on May 24, 1911, with regard to the sale of the cotton waste, and that after that conversation and in confirmation of it the plaintiff wrote to the defendants a letter in substance as follows:

"May 24th, 1911. Messrs. Boston Fibre Co., Boston Mass. Gentlemen: We confirm our today's phone conversation with

Page 233

Mr. Dooskin according to which we have sold you all that we have on hand of our lot 'WAS' Screen, like the carload of 40 bales you recently purchased from another party, at 2c per lb. fob cars Manchester, N. H. for shipment 1/2 on the 5th of June and on the 12th of June. We advised you at the time, that there is 25,000 lbs. on hand, but we may have a little more by that time altho' the Mill is going to shut down all of next week. If there should be 5/10 bales more than our estimate we don't suppose it will make any difference.

"Also 200 bales in addition to what we have on hand, to be shipped as soon as a carload is accumulated at the same price as above. Terms are to be 30 days net.

"Kindly confirm purchase to us and give shipping instructions in due season, so that we can get the lot away on time, in accordance with the order."

On the same day the defendant signed and delivered to the plaintiff the order of which the following is a reduced photographic facsimile:

The defendants offered evidence tending to explain the meaning of the words "if desired," as used in the above order, and the evidence was excluded, the judge ruling as follows, subject to

Page 234

exceptions by the defendants: "I shall rule for the present that this is not an option as a matter of law. I am going to rule that those two papers constitute the contract and I shall also rule that the two hundred bales were not an option. That is my construction of those two papers and I so rule for the present and we will go on and try out the case on the question of warranty."

Other material evidence is described in the opinion.

At the close of the evidence the defendants asked for the following rulings among others: "It is a question of fact for the jury on the evidence and in view of all the conversations in evidence whether or not the two hundred bales was to be construed as an option.

"The question as to the ambiguity of the contract as shown by the words 'if desired' in the order 'No 01' is a question for the jury."

Subject to exceptions by the defendants the judge refused to rule as requested and charged the jury as a matter of law in substance that the words "if desired" referred to the words "To Be shiped about 25000 monetly."

The jury found for the plaintiff in the sum of $583.71; and the defendants alleged exceptions.

E. Greenhood, for the defendants.

J. Wasserman, (M. M. Horblit with him,) for the plaintiff.

CROSBY, J. This is an action for damages for the alleged breach of a contract by the defendants because of their refusal to accept and pay for two hundred bales (one hundred thousand pounds) of cotton waste or screen.

The plaintiff and the defendants had a conversation by telephone relating to the sale by the plaintiff to the defendants of the cotton waste on May 24, 1911, and there was evidence to show that as a result of this conversation and as confirmatory of the oral agreement between the parties a written order was sent by the defendants to the plaintiff and a letter was sent by the plaintiff to the defendants. The order and letter, each being dated May 24, 1911, include a purchase and sale of one hundred bales of waste or screen in addition to the two hundred bales which are the subject of the present action.

The case seems to have been tried by both parties upon the assumption that whatever oral contract had been made between

Page 235

them was merged in the letter and the order above referred to. The bill of exceptions states that "the issue tried was with reference to these two hundred bales under the third item of said order." The judge in his charge to the jury refers to the order and letter as confirming the contract entered into originally by telephone, with the apparent acquiescence of both parties. Under the circumstances, we treat the order and letter as constituting a valid contract, it having been so considered by the parties and the presiding judge. No question as to the statute of frauds arises, and it is not in issue under the pleadings. The principal, if not the only question raised by the bill of exceptions which has not been expressly waived by the defendants relates to the proper construction of the words "if desired," in the written order of May 24, sent by the defendants to the plaintiff and accepted by the plaintiff in his letter of the same date.

The plaintiff contended, and the trial judge ruled in substance, that these words related solely to the time of shipment, and that the order was not to be construed as an option. The judge refused to rule that the contract was ambiguous and declined to submit the question to the jury as to whether the words "if desired" related to the time of shipment or gave the defendants the option of accepting or declining to take the two hundred bales as they might elect.

The defendants contended that the words used constituted an option to purchase, or at least that the contract was ambiguous, and that extrinsic evidence was admissible to explain its meaning as used by the parties.

It is well settled that the construction of a written contract which is plain in its terms and free from ambiguity presents a question of law for the court; and to leave the interpretation of such a contract to a jury would be manifest error. On the other hand it is a familiar principle that where a contract is so expressed as to leave its meaning obscure, uncertain or doubtful, evidence of the circumstances and conditions under which it was entered into are admissible, not to contradict, enlarge or vary its terms by parol, but for the purpose of ascertaining the true meaning of its language as used by the parties. Strong v. Carver Cotton Gin Co. 197 Mass. 53. Sleeper v. Nicholson, 201 Mass. 110. Jennings v. Puffer, 203 Mass. 534.

Page 236

When the words "if desired" are considered in interpreting the meaning of the order, especially in view of the physical position in which they appear upon the order, we are of opinion that it could not be ruled that these words related only to the time of shipment of the waste, as matter of law, but that there was enough of doubt and uncertainty as to their meaning, and consequently of the construction of the contract as a whole, to require the submission of the question to the jury; and that evidence of the conditions and circumstances under which the contract was made and of the facts to which it related should have been admitted so far as they had a legitimate bearing upon the proper interpretation of the language used.

We do not decide whether the order and letter constitute a contract between the parties. See Lyman B. Brooks Co. v. Wilson, 218 Mass. 205.

Because of the exclusion of evidence of this character offered by the defendants, and because of the ruling that the contract did not constitute an option and that it was not ambiguous and therefore that its interpretation was not for the jury, the entry must be

Exceptions sustained.