CHARLES EKLON vs. CITY OF CHELSEA

CHARLES EKLON vs. CITY OF CHELSEA

Way, Public. Evidence, Presumptions and burden of proof.

Where a public highway once has been established it remains a public highway until it is discontinued as such by a duly authorized public board or officer or until the place of its location is given over lawfully to some other purpose.

A public use of land, when established, is presumed to continue unless its lawful extinguishment is shown affirmatively.

Page 214

The facts that the park commissioners of a city, acting under proper authority, "set out with shrubbery and laid out in grass" an area adjoining a highway and constructed round it a brick walk with a curbing, a part of which was within the limits of the highway, do not deprive of its character the part of the highway occupied by the brick walk and its curbing, and the city is liable to a traveller who sustains an injury from a defect in the curbing of this part of the brick walk of which the city had notice.

TORT under R. L. c. 51, § 18, for personal injuries sustained by the plaintiff on July 3, 1912, by reason of a defect in the curbing of a sidewalk in Broadway, a public highway of the defendant. Writ dated February 4, 1913.

In the Superior Court the case was tried before White, J. The evidence upon the only point now material is described in the opinion. The judge, as stated in his report, "submitted to the jury three questions and stated to them that this was not a case in which they were to render a verdict for the plaintiff or for the defendant, but they were to treat the case, so far as their treatment was concerned, as though the sidewalk outside the closed iron fence was a part of the sidewalks of the city and not a part of a park."

In answer to the questions submitted to them the jury found that the plaintiff was in the exercise of due care and that the accident happened solely on account of the negligence of the defendant, and assessed the damages in the sum of $3,500. The judge then ordered a verdict for the defendant, and reported the case for determination by this court. If the plaintiff was entitled to recover, judgment was to be entered for him in the sum of $3,500 and costs; otherwise, judgment was to be entered for the defendant.

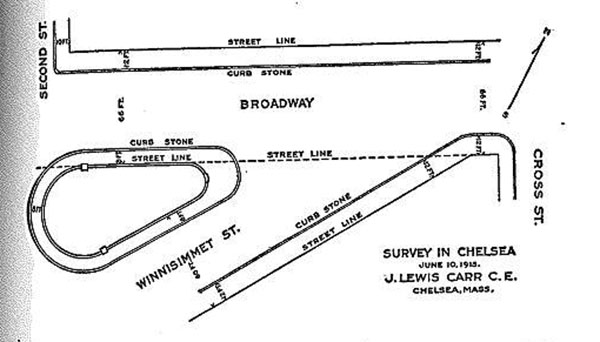

A reduced copy of the essential features of a plan which was used at the trial is printed on page 215.

R. W. Frost, for the plaintiff.

S. R. Cutler, for the defendant.

RUGG, C. J. This is an action to recover damages for injuries sustained by a traveller at a place alleged to be a public way in the defendant city. The only question is, whether as matter of law the place where the plaintiff was hurt was within a public way. The pertinent facts are that in 1871 that place was within the limits of a highway called Broadway, which then was widened so as to include it. The city of Chelsea seasonably accepted St. 1892, c. 325, whereby it was authorized "to use so much of Broadway

Page 215

square in said city as may be necessary for the purposes of a parkway or park." In July, 1896, after the enactment of St. 1895, c. 325, which authorized the city to incur indebtedness not exceeding $100,000, beyond the limits fixed by law, for "acquiring and improving open spaces for park, parkway and playground purposes," the board of aldermen (being the proper board to pass such an order) voted to appropriate $10,000, to be expended under the direction of the park commissioners for the improvement of Winnisimmet Square. The park commissioners, under that vote,

constructed the whole area included within a curb, the middle portion being "set out with shrubbery and laid out in grass." Outside" of this was a brick walk and a curb, where the plaintiff was injured, which was within the limits of Broadway as widened in 1871.

It does not appear that any taking of land by written instrument or plan was made by the park commissioners. Doubtless, under some circumstances, a physical seizure of private property may constitute a taking under the power of eminent domain, Bryant v. Pittsfield, 199 Mass. 530, yet a mere change from one public board or officer to another in the care and maintenance of a part of a highway, without more, is not enough to constitute an extinguishment of the highway. There is nothing in the record to show that Broadway Square or Winnisimmet Square had a definite location. It does not appear where either of these squares is, or whether they are different squares or the same square with different names.

Page 216

St. 1892, c. 325, authorizes only the use of Broadway Square, but not of Broadway, for a park or parkway.

This record fails to show that the place where the plaintiff was injured had ceased to be a highway. It was once appropriated to that public use. It continued to be a place of public travel. The presumption is that a lawful public use, once established, continues until it explicitly appears that the place has been given over lawfully to some other purpose. Land taken for one public use may be devoted to another public use only by legislative authority clearly expressed, whose mandate as to the method of actually making the change must be exactly followed. But whether there has been such change cannot be left to an indefinite surmise. If made, its nature and extent must be established by unequivocal acts. Higginson v. Treasurer & School House Commissioners of Boston, 212 Mass. 583, 591. When a highway is laid out, it cannot be discontinued or put to another use except by some public and notorious act of a duly authorized public board or officer. There is nothing to show that the proper officers of Chelsea have discontinued as a public way the part of Broadway where the accident occurred. It is not possible upon this record to go further than to say that as matter of law the place in question remained within the limits of Broadway, which as a highway the defendant was bound to maintain in a condition reasonably safe and convenient for public travel.

In accordance with the terms of the report, let the entry be

Judgment for the plaintiff in the sum of $3,500 and costs.