MARGARET F. CONRY, administratrix, vs. BOSTON AND MAINE RAILROAD.

MARGARET F. CONRY, administratrix, vs. BOSTON AND MAINE RAILROAD.

Negligence, Due care of plaintiff's decedent, Railroad, Causing death. Evidence, Admissions, Relevancy. Practice, Civil, Conduct of trial: judge's charge; Exceptions.

At the trial of an action by an administrator of the estate of a woman against a railroad corporation for causing the death of the plaintiff's intestate previous to the enactment of St. 1914, c. 553, there was evidence that the intestate, in order to go to a station of the defendant to procure a time table, had come from her home on a street in a city that ended in a fence at the edge of the railroad location on the opposite side of the tracks from a station building, had passed through an opening in the fence provided with posts about two feet apart and made suitable for entrance and exit from that street to the railroad premises, had crossed double tracks and had entered the station; that, returning from the station at a time over half an hour before any train was due to stop at the station, she looked both ways and saw no train; that then she took in her arms a child that was with her and started across the track, looking again in both directions when between the tracks; that smoke and steam from a freight train that then was passing under a bridge one hundred and seventy feet to her right obscured to some degree the view of an express train approaching from that direction; that, as she was stepping off the last track, she was struck by the express train which was running at the rate of fifty to sixty miles an hour without giving any warning by bell or whistle and which at the bridge had been running at the rate of from thirty to thirty-five miles an hour. Held, that there was evidence that when struck the intestate was in the active exercise of due care, and that her death was caused by negligence for which the defendant was accountable under St. 1906, c. 463, Part I, § 63, as amended by St. 1907, c. 392, § 1.

At the trial of the above described action, the plaintiff, subject to an exception by the defendant, was permitted to show that, after the accident, the defendant had erected a fence between the tracks in front of the station which prevented passage to and from the station from and to the street whence the plaintiff's intestate bad come, the evidence being specifically limited to the issue, whether "it was physically possible and practically possible to build such a fence and to maintain such a fence in the conduct of the business of the defendant." There was no evidence that the defendant contended that it was either impossible or impracticable to erect and maintain such a fence. Held, that the evidence should not have been admitted.

Referring to the evidence, above described, at the close of his charge to the jury, the presiding judge stated, "The fact that the defendant did not maintain a fence between the inward and outward bound tracks cannot be considered as evidence of negligence at that time." Held, that this instruction was not sufficient

Page 412

in form to eradicate from the minds of the jury the effect, prejudicial to the defendant, of the evidence improperly admitted.

It also was stated that, in order to cure the error in the admission of the evidence above described, the judge should have instructed the jury to disregard for any purpose of proof the fact that a fence had been erected by the defendant between the tracks after the accident.

TORT for causing the death of the plaintiff's intestate, Annie Cullen, on June 4, 1913. Writ dated August 16, 1913.

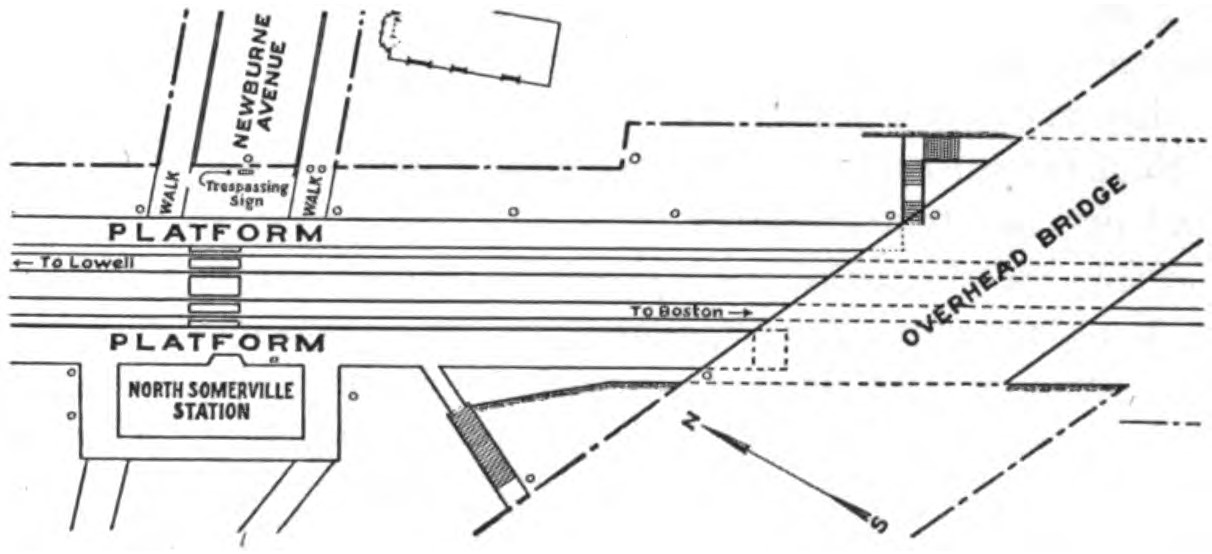

In the Superior Court the action was tried before Hitchcock, J. The material evidence and exceptions saved by the defendant are described in the opinion. A reduced copy of a plan which was in evidence and which shows the location and surroundings of the place of the accident is shown on page 413. There was a verdict for the plaintiff in the sum of $5,000; and the defendant alleged exceptions.

The case was argued at the bar in March, 1917, before Rugg, C. J., Crosby, Pierce, & Carroll, JJ., and afterwards was submitted on briefs to all the justices.

F. N. Wier, (J. M. O'Donoghue with him,) for the defendant.

H. D. McLellan, (B. A. Brickley with him,) for the plaintiff.

PIERCE, J. The plaintiff's intestate, Annie Cullen, was struck and killed by a passenger train bound from Boston to Lowell, while crossing the defendant's tracks in front of the North Somerville station, about three o'clock in the afternoon of June 4, 1913. She lived on Newburn Avenue, Somerville, which ran from the easterly side of the railroad location. On this side and extending across Newburn Avenue was a fence, in the centre of which an opening with posts about two feet apart made a suitable entrance for pedestrians from Newburn Avenue to the railroad premises and a suitable exit from there to the avenue. The station building was on the westerly side of the railroad tracks opposite Newburn Avenue. A concrete platform extended along the tracks in front of the station and for a distance of about one hundred feet north and south beyond the building. There was a corresponding platform of about the same distance on the easterly side of the tracks. In front of the station building a space fifteen feet in width was covered with planking between the rails and between the platform and the rails and extended across the tracks. The tracks were straight for a distance of at least half a mile from the station in both directions. No train going

Page 413

north was due to stop at the station until 3:51 P. M. and none going south until 3:40 P. M.

The intestate went to the station to obtain a time-table, intending to take a train later in the day. She stood on the station platform, and, as soon as a freight train going south toward Boston passed, she took the child who was with her in her arms and started across the tracks on the planked space. There was evidence that before starting she looked "toward Boston and the opposite way," that she again looked in both directions when she got between the inbound and outbound tracks, and that the train was not then in sight. There was evidence that smoke or steam from the engine of a freight train then passing under a bridge one

hundred and seventy feet south from the place of the accident, obscured to some degree the view of the bridge under which the train from Boston passed; that the train from Boston as it approached the bridge was going about twenty-five miles an hour, that at the bridge the speed was thirty to thirty-five miles an hour and at the place and time of accident had increased to fifty or sixty miles an hour. There was also evidence that no notice was given of the approach of the train by the ringing of a bell or otherwise. The intestate was struck by the engine as she had her foot ready to step upon the platform. At the close of the evidence the defendant moved that a verdict be directed in its favor. This motion was denied and the jury found for the plaintiff.

In the opinion of a majority of the court there was evidence for the jury of the plaintiff's due care. Giaccobe v. Boston Elevated Railway, 215 Mass. 224. Lunderkin v. Boston Elevated Railway, 211 Mass. 144. So far as appeared she had no reason to anticipate

Page 414

the passage of a train at that time and she could be found to have been affirmatively careful and diligent in self protection. McCue v. Boston Elevated Railway, 221 Mass. 432.

When she stood in the space between the inbound and outbound tracks no train was in sight. If she saw the train come out from the bridge when she stepped on the outbound track, the jury could find that a reasonable person, affirmatively diligent in self protection, would not have anticipated that the speed of the train would be increased from thirty to sixty miles an hour in its passage over one hundred and seventy feet of space. Hunt v. Old Colony Street Railway, 206 Mass. 11.

There was also evidence to warrant a finding of the defendant's negligence in running its train past a station at the rate of speed shown by the evidence, at a time when passengers and others were invited to cross the tracks.

Subject to an exception by the defendant, evidence was admitted that after the accident a fence was erected between the inbound and outbound tracks at the North Somerville station, not as evidence on the question of the particular act of negligence but "only for the purpose of showing that it was physically possible and practically possible to build such a fence and to maintain such a fence in the conduct of the business of the defendant company." The evidence was not admissible to prove the negligence of the defendant. Shinners v. Proprietors of Locks & Canals, 154 Mass. 168. And it was not admissible to prove that it was "physically possible and practically possible to build such a fence and to maintain such a fence in the conduct of the business of the defendant company" because there was no evidence that the defendant contended that it was either impossible or impracticable to erect and maintain the fence as it was in fact erected. The case of Beverley v. Boston Elevated Railway, 194 Mass. 450, is not an authority for the admission of the evidence. The defendant in that case as shown by the bill of exceptions admitted the possibility of the change but denied that it was practicable. A distinct issue of fact was thus presented, and the evidence was admitted merely for the purpose of showing what was practicable in the use of the station. That the evidence was prejudicial in the highest degree is indisputable; the logic of the events would inevitably lead the jury to a conclusion that the defendant had recognized the danger

Page 415

and had taken the precaution to prevent other accidents by making it impossible to pass from one platform to the other across the tracks. We do not think the statement of the judge to the jury at the close of the charge, that "The fact that the defendant did not maintain a fence between the inward and outward bound tracks cannot be considered as evidence of negligence at that time," was sufficient in form or force to eradicate from the minds of the jury the effect of the admitted evidence. To accomplish this end they should have been told that the evidence was admitted improperly and explicitly enjoined to disregard for any purpose of proof the fact that a fence had been erected by the defendant between the tracks since the accident.

Exceptions sustained.