MICHAEL A. CAVANAUGH & another vs. D. W. RANLET COMPANY.

MICHAEL A. CAVANAUGH & another vs. D. W. RANLET COMPANY.

Sale, Warranty. Contract, Performance and breach, Rescission, What constitutes. Conflict of Laws. Frauds, Statute of. Waiver. Estoppel. Words, "Arrival."

Where, at the trial of an action for breach of a warranty of the quality of oats sold by the defendant to the plaintiff and to be delivered to the plaintiff at a city in New Hampshire, there is no evidence of the law of that State, the rights of the parties are to be determined at common law.

Where, at the trial of an action for a breach of a warranty of quality in an oral contract of sale to the plaintiff of four carloads of oats, it appears that three of the carloads were accepted by the plaintiff and were paid for, the statute of frauds is not a defence.

The mere facts, that a carload of oats was shipped by a bill of lading to the seller's order, that the bill of lading was indorsed by the seller and was attached to a draft upon the purchaser for the amount of the purchase price less the freight, and that the purchaser, without examining the contents of the car, paid the draft and received the carload, do not as a matter of law estop the purchaser from rescinding the sale upon discovering that the oats are not of the quality which he agreed to purchase, where there is evidence that, upon making such discovery, he notified the seller thereof and demanded back the purchase price; but the question, whether the purchaser waived the warranty, is to be determined as a question of fact.

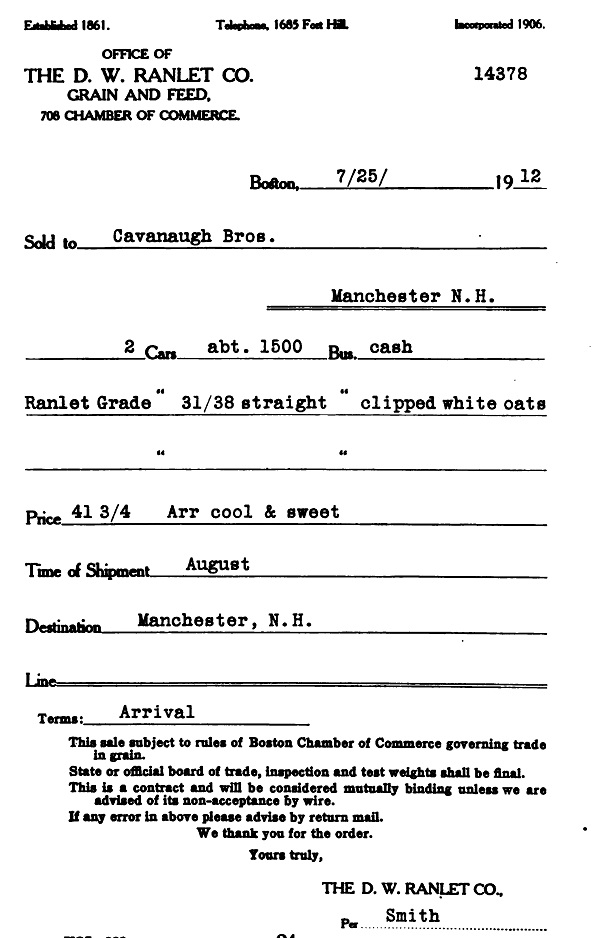

A memorandum, sent by a seller to a purchaser and containing the terms of a proposed sale and the words "This is a contract and will be considered mutually binding unless we are advised of its non-acceptance by wire," and "If any error in above please advise by return mail," is an offer to sell the goods, upon an acceptance of which by the prospective purchaser a binding sale would arise.

Page 367

It could not be ruled as a matter of law that the mere failure of the prospective purchaser to reply to the memorandum above described effected an acceptance so that a binding sale resulted, and, in an action on the alleged contract, it is for the jury to say whether under all the circumstances the silence of the alleged purchaser amounted to an assent.

Where, at the trial of an action for breach of a warranty of the quality of a carload of oats sold by the defendant to the plaintiff, to be delivered in a certain city, there is evidence upon which, under suitable instructions, the jury would have been warranted in finding that before the oats reached that city they were in a condition unfit for sale, it would be improper for the judge to order a verdict for the defendant although there was a provision of the contract of sale which required him to examine the oats and to notify the seller of any failure of them to conform to the warranty "not later than the following business day after arrival of the car at destination."

Upon the evidence at the trial above described, and under suitable instructions, it further was held, that the jury would have been warranted in finding that the word "arrival" in the rule above described was understood and intended by the parties to mean that, until the car had been detached and placed on a siding where it could be reached, inspected and unloaded in the course of the carrier's business, and notice had been given to the purchaser, possession was not taken by the purchaser and the time within which he should notify the seller of a breach of warranty had not begun to run.

Where, therefore, under such circumstances, there was further evidence warranting findings that the carrier made a mistake in placing the car where it still remained inaccessible, that, immediately upon rectification of such error, inspection by the purchaser followed, the breach of warranty was discovered and the seller was notified of that fact on the following day by telephone, it could not properly have been ruled as a matter of law that the defence of noncompliance by the purchaser with the rule above described, if that rule was a part of the contract of sale, had been proved.

CONTRACT , originally brought by Michael A., Thomas F. and James F. Cavanaugh, doing business as a copartnership under the name Cavanaugh Brothers, to whom afterwards was added as a plaintiff James Reid, with a declaration, as amended, in three counts. In the first count the plaintiffs alleged in substance that they purchased of the defendant a carload of straight clipped white oats that were guaranteed to be cool and sweet and paid the defendant therefor, but that the defendant never had delivered the oats to them. In the second count they alleged in substance that they and the defendant entered into an agreement whereby the defendant was to deliver to them two carloads of oats in August, 1912, and two carloads in December, 1912, for which they were to pay the defendant certain prices, respectively, less the freight on each car, by draft attached to the bill of lading; that the agreement was fully performed by both parties as to all excepting the

Page 368

second carload; that the second carload arrived in the freight yard at Manchester, New Hampshire, where the plaintiffs were, in September, 1912, and that the plaintiffs were obliged to pay $537.93 upon the draft attached to the bill of lading thereof without having had an opportunity to examine the contents of the car; that the contents were examined as soon as possible thereafter and were found to be in a condition not fit for use; that the plaintiffs thereupon immediately notified the defendant and demanded of the defendant the sum of money paid to it for the carload, but the defendant refused to repay such sum to the plaintiffs. In the third count the plaintiffs alleged that they paid to the defendant $537.93 for which there was no consideration and that, although often requested to return such sum, the defendant had refused so to do. Writ dated December 1, 1914.

The answer, besides containing allegations of general denial and payment, set up the statute of frauds.

In the Superior Court the case was tried before Keating, J.

There was evidence introduced by the plaintiffs that one of them called the office of the defendant in Boston on the telephone, asked for the oats salesman, inquired how the market was on oats, was quoted a price for immediate shipment, ordered two cars to be delivered in a couple of weeks, when the defendant "could get them to us," and two for December shipment; that he had been buying oats from the defendant right along, and that it did not need much talk, because he was always getting what he bought; that he told the salesman that he wanted "number Two white oats, clipped white oats, to be cool and sweet," and was told that he could have them. The testimony of the defendant's salesman did not agree with this last statement. The salesman testified that nothing was said about the grain being cool and sweet.

After the telephone communication, the defendant sent by mail to the plaintiffs two papers, called in the record "confirmations," one referring to the cars for immediate shipment, and one to those for December shipment. These were received by the plaintiffs' bookkeeper. The plaintiffs' evidence tended to show that the bookeeper said nothing to the plaintiffs about them. The paper referring to the carload in question in this action was as follows:

Page 369

Page 370

The carload of oats in question was billed to the order of the defendant at Manchester, New Hampshire, and the bill of lading was indorsed by the defendant and was attached to a draft for the purchase price less the freight and the draft with the bill of lading attached was placed in a Boston bank for collection and was forwarded to a Manchester bank where the plaintiff Reid paid it and received the bill of lading.

Other evidence is described in the opinion. At the close of the evidence the judge ordered a verdict for the defendant and reported the case for determination by this court, the parties having stipulated that if, upon the competent and admissible evidence, the ruling was right, judgment should be entered for the defendant; but, if upon the evidence the jury were warranted in returning a verdict for the plaintiff Reid, judgment was to be entered for the plaintiff in the sum of $645.52.

It further was stipulated that it was to be made a part of the record that the plaintiffs Cavanaugh disclaimed any right, title or interest in the action and in the subject matter of the contract concerning which the action was brought, and assented to the maintenance of the action by the plaintiff Reid for his personal benefit.

After the trial of the case (it having appeared in evidence at the trial that the Boston and Maine Railroad had in its possession $306.23, over and above its charges, from the sale of the car of oats in question), the parties by mutual agreement and with the express stipulation that it should be without prejudice in any event to either party, by joint order withdrew from the Boston and Maine Railroad and paid over to the plaintiffs that sum and the plaintiffs released the trustee to that extent, and it was agreed that in the event of a judgment for the plaintiffs that sum should be credited on the judgment, so that, in the event of judgment for the plaintiffs, execution should be issued in the sum of $339.29 with interest from February 14, 1916, and costs.

F. J. Smith, for the plaintiffs.

A. T. Johnson, for the defendant.

BRALEY, J. The question for decision is whether the verdict for the defendant was ordered rightly.

It is undisputed that the plaintiffs doing business in Manchester, New Hampshire, purchased at an agreed price of the defendant

Page 371

doing business in Boston, Massachusetts, as a wholesale jobber of grain which it bought and sold in car lots, four carloads of "clipped white oats, to be cool and sweet," delivery to be made at Manchester where the sale was consummated. But, as no evidence of the law of that State was introduced, the rights of the parties are to be determined at common law. Callender, McAuslan & Troup Co. v. Flint, 187 Mass. 104.

The oral contract relied on by the plaintiffs being entire, and three cars having been accepted and the price paid, the statute of frauds is not a defence. Roach v. Lane, 226 Mass. 598. Townsend v. Hargraves, 118 Mass. 325.

A sale of goods by a particular description includes a warranty that the goods shall conform to the description, and counsel for the defendant makes no contention that the words "cool and sweet" are not words of warranty. Gould v. Stein, 149 Mass. 570. Fullam v. Wright & Colton Wire Cloth Co. 196 Mass. 474, 476. Gascoigne v. Cary Brick Co. 217 Mass. 302. The defendant also never has denied that the oats in question which came in the second car were not soft and were in a general state of heat and fermentation when inspected by one Reid, a buyer from the plaintiffs of the shipment.

But, even if the draft for the price attached to the bill of lading, which Cavanaugh Brothers indorsed to Reid, was paid by him, no estoppel barring rescission arises. The jury were to decide whether the warranty had been waived by an acceptance of damaged goods, considered in connection with the undisputed fact, that notice was given to the defendant of the breach, with a claim for reclamation. Trimount Lumber Co. v. Murdough, ante, 254, and cases cited.

What has been said rests upon the oral contract, which, notwithstanding the defendant's denial, the jury could find resulted from the conversation by telephone between the contracting parties. The defendant however contends that the contract was in writing. The credibility of the witnesses was for the jury. It could be found that even if the exhibit, referred to in the record as a "confirmation," with the invoices of weight and condition had been mailed by the defendant and received by the bookkeeper, yet the plaintiffs never were shown the correspondence nor made acquainted with the contents. If this exhibit is examined, the

Page 372

word "confirmation" is not found. It purports to be a memorandum of a sale of two cars "straight clipped white oats," one of which is the car in question, with a statement of the price, warranty and terms of shipment. It does not purport to confirm the oral contract. It is of itself an offer to sell which upon acceptance by the offerees would become a binding sale. The words, "This is a contract and will be considered mutually binding unless we are advised of its non-acceptance by wire. If any error in above please advise by return mail," immediately preceding the defendant's signature, admit of no other satisfactory construction. It could not be ruled as matter of law, that, if the "confirmation" were treated as an offer, it became a binding agreement from the failure of the plaintiffs to reply. The jury under all the circumstances were to say whether the plaintiffs' silence amounted to an assent. Quintard v. Bacon, 99 Mass. 185. Borrowscale v. Bosworth, 99 Mass. 378. Metropolitan Coal Co. v. Boutell Transportation & Towing Co. 185 Mass. 391, 395. If the jury found the oral contract had not been established, then, if accepted by the plaintiffs, the "confirmation" would constitute the contract. Metropolitan Coal Co. v. Boutell Transportation & Towing Co. ubi supra. But, if they found the oral contract had been proved, the further question, whether that contract had been mutually modified, rescinded or abandoned, was a question of fact under suitable instructions. Hanson & Parker, Ltd. v. Wittenberg, 205 Mass. 319, 326, and cases cited.

The defendant's next contention goes on the assumption that the "confirmation" is the contract. If so, the rules of the Boston Chamber of Commerce were incorporated by reference, whereby if the goods are not according to the warranty, the "Seller shall be notified not later than the following business day after arrival of car at destination, and be given an opportunity to order inspection, if so desired by him." And as the notice given was not within the designated time, the plaintiffs cannot recover. But the answer is, that on ample evidence the jury could say that the oats were in a damaged condition before the train entered Manchester. The buyers moreover were not bound to take the oats in whatever condition they might be in, and under appropriate instructions it could have been found that the word "arrival" appearing in the "confirmation," even if read with the rules, was

Page 373

understood and intended by the parties to mean, that until the car had been detached and placed on a siding where it could be reached, inspected and unloaded in the course of the carrier's business and notice given to the plaintiffs or to their vendee, possession had not been taken and the warranty had not been waived nor discharged. Alden v. Hart, 161 Mass. 576. Bachant v. Boston & Maine Railroad, 187 Mass. 392, 393. Garvan v. New York Central & Hudson River Railroad, 210 Mass. 275, 280. Pope v. Allis, 115 U. S. 363. A finding also would have been warranted that, if at first the carrier made a mistake in placing the car where it still remained inaccessible, upon rectification of the error, inspection immediately followed, with notice to the defendant the following day by telephone of the condition of the oats and of non-acceptance. It is manifest without further comment that upon confiicting evidence and the inferences therefrom which the jury could draw the presiding judge could not properly rule that the defence had been maintained.

We perceive no reversible error in so far as argued to the admission of evidence to which the defendant excepted, and, the plaintiffs having been entitled to go to the jury on every material aspect of the case, the verdict cannot stand.

The defendant, however, if this is the result, raises no question of misjoinder. If for want of privity the plaintiff Reid could not have prevailed in an independent action, the report states, that the action is to be considered as if instituted in the name of the Cavanaughs for his sole benefit, and by agreement of parties if the case should have been submitted to the jury he is to have judgment for the amount therein stipulated with interest and costs. Bryne v. Dorey, 221 Mass. 399, 406.

So ordered.