HIPPODROME AMUSEMENT COMPANY vs. IGNATZ WIT.

HIPPODROME AMUSEMENT COMPANY vs. IGNATZ WIT.

Landlord and Tenant, Construction of lease. Contract, Construction, Validity. Equity Jurisdiction, To avoid unconscionable contract.

A lease for a term of thirty-two years of four parcels of land in a city, denominated in the lease by reference to a sketch plan as lots A, B, C and D, provided for a

Page 217

fixed rent for parcels A and B, and that the rent to be paid for lots C and D should be nine per cent of the valuation of those lots as assessed by the proper authorities of the city "or those having the power in the premises to value said land for the purpose of taxation." Lots A and B, which comprised about one third of the area of the four lots, were contiguous to a principal street of the city, and, dissociated from the other lots, had a value of about $30 per square foot. The other two lots, away from the street, had a value, if dissociated from lots A and B, of $5 per square foot. In the negotiations leading up to the lease, all parties knew that there was a great difference in value between the two groups of lots. The assessors of the city before the making of the lease had assessed the four lots together as a part of a larger parcel at $12 per square foot, which, as a uniform rate for all four parcels, was a reasonable assessment. The lessee sought to have the assessors assess lots C and D separately. The lessor objected to this being done, and the assessors refused to do it in the face of the objection. The lessor claimed as rent of lots C and D nine per cent of the valuation at $12 per square foot. The lessee, asserting that such a rent was unconscionable and was not intended by the parties, brought a bill in equity seeking to enjoin the lessor from interfering with the assessors' assessing the lots C and D separately, to have the court determine, "by special assessment or otherwise," the fair assessable value of lots C and D, and to have an accounting as to rents paid and to be paid. Held, that the bill must be dismissed as the plaintiff executed the contract voluntarily and deliberately with knowledge of the facts and without any misrepresentation or fraud on the part of the lessor and therefore was bound by its plain provisions.

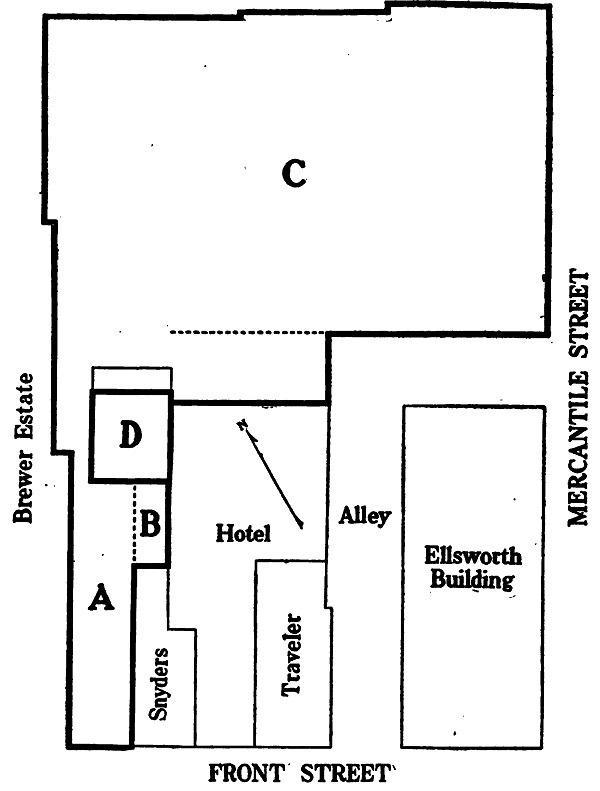

BILL IN EQUITY , filed in the Superior Court on February 20, 1917, alleging that the plaintiff and the defendant on March 23, 1914, entered into a leasehold agreement whereby the defendant let to the plaintiff for a period of thirty-two years the lots marked A, B, C and D on an accompanying plan, a copy of which is printed on page 218, a fixed rent being agreed upon as to lots A and B, as to which there was no dispute; that the provision as to the rent to be paid for lot C was as follows: "For said Parcel C a yearly rental of a sum equal to nine (9) per cent of the valuation of said Parcel C as assessed by the proper authorities of the City of Worcester or those having the power in the premises to value said land for the purpose of taxation, such percentum to be based on such tax valuation as of April 1 in each year for the year ending the following March 31, and if the assessment date shall hereafter be changed, then the rental year shall begin as of such assessment date;" and that the provisions as to lot D were as follows: "The land upon which said kitchen stands [Lot D] is now under lease to persons other than this Lessee. If the Lessee herein named secures a cancellation of said lease so far

Page 218

as it relates to the said land upon which said kitchen stands, then said land upon which said kitchen stands is hereby demised and let to this Lessee from the date of such cancellation during the remainder

of the term hereby created, to wit, to March 31, 1946, and is hereby referred to as Parcel D, and rent therefor shall be paid at the same rate as provided above as to Parcel C."

The plaintiff further alleged that Front Street, shown on the

Page 219

plan, was one of the principal business streets of Worcester and that the land on the street was of large rental value and that land at a considerable distance from it, as were lots C and D, was of much less rental value; that it was contemplated at the time of the making of the agreement that certain buildings on the premises should be torn down and a theatre building erected on lots C and D.

Further allegations were that, previous to the execution of the agreement, the assessors of taxes of Worcester had assessed the land, including lots A, B, C and D and other and adjoining land, all being owned by one person, as one parcel; that, in order to ascertain what the fair and proper rent of the parcels C and D was, under the terms of the lease, it was necessary that they be assessed separately from the rest of the land; that the plaintiff had tried to get the assessors to make such a separate assessment of lots C and D, and that the defendant had requested them not to make such separate assessments and had taken active measures to prevent any such separate assessment being made, and that he, the defendant, contended that he was entitled to rent under the agreement based on the old valuation per square foot; that for the defendant to collect such rent was "a direct violation of the provisions of said lease," but that, if he was successful in preventing the separate assessment of lots C and D, he might be able to compel the plaintiff to pay as rent "a much higher rate than is just and equitable and that was contemplated and provided for in the said lease itself."

It also was alleged that the assessors were willing to make a separate assessment of lots C and D, but that they asserted that they were requested not to do so by the defendant and that they did not wish to make any such special assessment in the face of the defendant's objections.

The prayers of the bill were that the defendant might be directed to cease from interfering in the matter and to consent to a special assessment being made of said lots C and D by the assessors; that the court should determine, by special assessment or otherwise, the fair assessable value of lots C and D from the date of the lease to April 1, 1917, the date of the next assessment by the assessors of Worcester; that, after such value had been ascertained by the court or otherwise, an accounting might be had to

Page 220

determine whether the defendant had been overpaid in the matter of rents paid for lots C and D, and, if so, to what amount; and for general relief.

The suit was heard by Jenney, J. He found in part as follows:

"The land included in lots D and C was at the time of the execution of the lease fairly worth $5 per square foot, and said land has not increased in value since that time. The front land, such as is included in lot A, is worth about $30 per foot separately and apart from the rear land. All parties in the negotiations which led up to the lease to the plaintiff knew that the front land was of much greater value than the rear land, but there was no evidence as to just what figures of value were in their minds.

"Beyond preparation of plans, the plaintiff did nothing toward the actual construction or erection of said theatre building until some time in the year 1916. It then began the erection of said building and the same was substantially completed when the bill was filed. The theatre building is so constructed as to be used in connection with the entrance thereto from Front Street over lot A; and the structure on said lot is adapted for and used only as an entrance to the theatre.

"The entire tract of land held by the defendant (under his lease from Leland) contains 13,122 square feet, and prior to this lease to the plaintiff this land had been assessed as a whole and at the uniform rate of $12 per square foot. I find that that rate was a reasonable assessment per square foot for the entire area, as a large part, nearly two-thirds of the total area, was back land."

"Wit personally and by solicitation of others endeavored to prevent the plaintiff's representatives from getting this separate assessment. He claimed to the assessors that he was the lessee of the entire property under his long lease and that it had always been assessed as one piece and should continue so to be assessed. Mrs. Kent, then the owner of the entire parcel, although under no obligation to pay any taxes on the property during the entire period of her lease to Wit, a matter of over thirty years, protested against any division of the lot for the purposes of assessment. I find that Wit's object in endeavoring to prevent a separate assessment of the rear land was, first, that he might very greatly increase the amount of rental to be collected by him upon lots C and D, and second, that he might impose upon the plaintiff a

Page 221

much larger proportion of the total annual taxes on the entire real estate than the plaintiff under the terms of the lease would bear in case of a separate assessment."

Other material findings of the judge are described in the opinion.

The judge ordered a decree that the bill be dismissed and, at the request of the plaintiff, reported the case with his findings of fact, but without a report of the evidence, to this court for determination.

The case was argued at the bar in November, 1918, before Rugg, C. J., Loring, Braley, Pierce, & Carroll, JJ., and afterwards was submitted on briefs to all the Justices.

F. N. Nay, (M. L. Levenson with him,) for the plaintiff.

A. K. Cohen, (H. A. Mintz with him,) for the defendant.

BRALEY, J. While the lease dated March 23, 1914, does not in terms refer to the sketch plan the bill alleges and the answer admits that the plan was followed in the description of the leasehold and the apportionment of the rent. It is apparent from the plan, on which the areas do not appear, that the demised premises comprise an entire tract divided into contiguous parcels, which are respectively designated as A, B, D and C and of which only parcel A abutted on a public way. The trial judge finds that at the execution of the lease this parcel, which is referred to by him and by counsel as "front land" had a value of about $30 a square foot, while parcels C and D or the "rear land" were each worth only $5 a square foot. But he also states that while the parties during the negotiations preceding the lease knew that the front land was of much greater value than the rear land, there was no evidence before him showing any estimate of valuation on which either party acted. The inquiry would be of little moment if it were not for the provisions of the lease which, instead of naming a round sum as a yearly rent for the entire leasehold, treats the parcels as if each parcel was a separate demise. The rent reserved for parcels A and B, concerning which there is no dispute, is a fixed yearly amount based on a graduated scale during the term and the lessor pays the taxes on lot A. But for parcel C, and for parcel D, subsequently acquired by the plaintiff as provided in the lease, the lessee covenanted to pay a yearly rent equal to nine per cent of the valuation of the parcels as assessed by the proper authorities of the city, "or those having the power in the premises

Page 222

to value said land for the purposes of taxation, such percentum to be based on such tax valuation as of April 1, in each year for the year ending the following March 31, and if the assessment date shall hereafter be changed, then the rental year shall begin as of such assessment date." While parcel C at the date of the lease was vacant land, the plaintiff as contemplated by the lease, has erected thereon a building to be used by it as a theatre, access to which by the public is over parcel A in connection with parcels B and D, and at the termination of the lease the building is to become the property of the lessor.

It appears from the record that the entire tract held by the defendant as the lessee of one Leland contains thirteen thousand one hundred and twenty-two square feet, while the premises demised to the plaintiff exclusive of lot A comprise eight thousand ninety-one square feet of which lot D has an area of three hundred and sixty and lot C an area of seven thousand six hundred and seven square feet.

The defendant demands rent for lots C and D on the basis of the taxable valuation of $12 per square foot, at which as a uniform rate the judge found that the land as a whole had been assessed to the defendant before the plaintiff's lease and that "that rate was a reasonable assessment per square foot for the entire area, as a large part, nearly two-thirds, of the total area, wras back land." The evidence is not reported, and this finding as well as the further finding that the total rent of lots C and D from the beginning of the term to and including March 31, 1917, computed at nine per cent on the valuation of the land as assessed prior to the lease at $12 a square foot, amounts to $42,994.11, of which sum the plaintiff has paid $36,460.13, leaving a balance due when the bill was filed of $6,533.98, cannot be disturbed. The bill, however, alleges and the plaintiff contends that in order to determine the fair and proper rent it is necessary that the assessors should make a separate assessment of lots C and D with the buildings thereon, and it is found that although so requested by the plaintiff, the assessors have declined to make a separate assessment because the owners of the reversion as well as the lessor decline to acquiesce in any division of the premises.

The plaintiff being confronted with this situation asks that the defendant may be decreed to consent to a "special assessment

Page 223

being made of . . . lots C and D . . ." or that the court "shall determine, by special assessment or otherwise, the fair assessable value . . . from the date of said lease to April 1, 1917, the date of the next assessment by the assessors . . ." If the plaintiff under the wording of the covenant is within the grip of a bargain which it now maintains is extremely burdensome and unduly advantageous to the lessor, the hardship arises as shown by the record from its voluntary and deliberate act in executing the lease, and not from any misrepresentation or fraudulent conduct of the defendant.

It is plain that the rent is to be ascertained on the valuation of the leasehold as a whole or in parts which may change from year to year as the assessors in the performance of their duties as public officers may in their own judgment determine. Wall v. Hinds, 4 Gray 256, 269. And, finding no error in the computation previously stated of the amount due from the plaintiff to the defendant, a majority of the court are of opinion that a decree in accordance with the terms of the report should be entered dismissing the bill.

Ordered accordingly.