JAMES F. FITZGERALD vs. ADELARD I. FORTIER.

JAMES F. FITZGERALD vs. ADELARD I. FORTIER.

Watercourse. Equity Pleading and Practice, Waiver.

The defendant in a suit in equity waived his right to be heard on his plea in abatement setting forth the pendency of a previous suit between the parties for the same cause, by agreeing to the reference of both suits to the same master, who accordingly heard them together.

The facts warranted the conclusion that a stream on certain land, which in places flowed through a well defined natural channel and in other places spread out without a definite channel, was a natural watercourse, though the source of the water was surface drainage from hills in the neighborhood, a part of the water was conducted to that land by artificial means, and the stream was dry at certain times of the year.

BILL IN EQUITY, filed in the Superior Court on March 12, 1934.

The report of a master was confirmed. By order of Williams, J., there were entered an interlocutory decree overruling the defendant's plea in abatement and a final decree in the plaintiff's favor. The defendant appealed from both decrees.

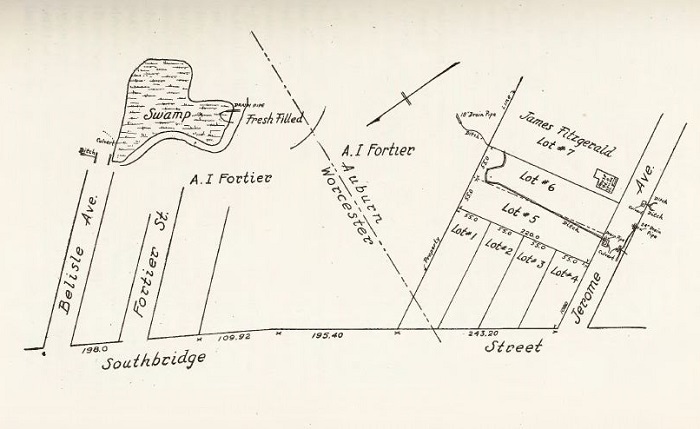

The sketch referred to in the opinion is set forth on page 269.

W. C. Mellish, for the defendant.

R. B. Dodge, for the plaintiff.

CROSBY, J. This is a suit in equity to restrain the defendant from flowing the plaintiff's land by obstructing the flow of a stream or brook. This suit and another brought by the same plaintiff against the same defendant were referred to a master, who states in his report that they were tried together before him and involved substantially identical issues. The master found that in the first suit the town of Auburn was originally a party defendant, but prior to the hearings that suit had been dismissed as to it; that the second suit

Page 269

Page 270

was brought without knowledge on the part of the present counsel of the fact that the earlier suit was pending, the plaintiff believing that it had not been filed by his former counsel. The master further found that counsel for the plaintiff stated during the hearings that he desired the second suit treated as supplementary to the original suit. On May 25, 1934, both parties agreed that the two suits be referred to a master and an order of reference was entered accordingly. In view of the facts that the defendant agreed to the reference of both suits to the same master, and that they were heard together, the defendant is deemed to have waived whatever rights he may have had to be heard upon his plea in abatement previously filed. The interlocutory decree overruling the plea in abatement is affirmed.

The master filed one report for both suits. He found the plaintiff's contention in substance to be that the defendant has caused, and is continuing to cause, a natural watercourse, which runs through the defendant's land, but not through the plaintiff's land, "to back up on to the plaintiff's land due to obstructions placed in its natural bed by the defendant, and has thus caused the plaintiff's land, on divers occasions, to be flooded causing him considerable damage in the enjoyment of his property and tangible damage to vegetation on his premises"; that the plaintiff and the defendant are contiguous land owners of certain premises located near Southbridge Street and about at the city line between Worcester and the town of Auburn; that the plaintiff's property, consisting of a lot of land bordering on Jerome Avenue, was acquired by the plaintiff in 1891 and is known as 7 Jerome Avenue, which has become a public street; that upon this lot the plaintiff in 1893 built a house facing Jerome Avenue; that toward the southeasterly end of Jerome Avenue and to the southeast the contour of the land is very hilly, resulting in a general slope and watershed toward Jerome Avenue; that the defendant purchased his property in three separate lots; that at the time the first two lots were purchased they were somewhat swampy and several feet lower than Southbridge Street; that in 1925 he started filling them in; that prior to the filling by the

Page 271

defendant "a well-defined channel meandered across the first two lots and eventually emptied into the culvert at Belisle Avenue, and that into this channel flowed the water which originally came from the culvert on Jerome Avenue"; that prior to the filling by the defendant on his land the plaintiff never was troubled with water backing up on his premises; that since the filling at least two or three times a year in the spring and fall water has backed up over the plaintiff's land, sometimes reaching almost to his house; that on at least two occasions water has backed up to such an extent as to cause water in the plaintiff's cellar, on one occasion to a depth of two feet, and at another time to a depth of one foot; that as a result of water backing up the plaintiff's garden and his fruit trees were destroyed; that the cause of the water backing up on the plaintiff's land was the obstruction by the defendant of the stream; that in the future it will cause water to back up on to the plaintiff's land, and result in serious damage to the plaintiff; and that at certain times of the year no water flows through the various channels described in his report, whereas at other times, particularly in the spring, the channels are completely filled with water. He further found that the opening in the culvert on the easterly side of Jerome Avenue is four feet in width and two and one half feet in height, and that the opening in the culvert under Belisle Avenue is four feet in width and two feet in height. He states: "Unless, because of the fact that the source of all the water involved in this case is surface water drainage and because of the fact that part of it has been led onto the defendant's land through the medium of artificially constructed ditches this stream is not a natural one as a matter of law, I find in so far as it is a question of fact that it is a natural water course and that its obstruction by the defendant as heretofore described will cause irreparable and continuous damage to the plaintiff's property"; that "As the injury in this case is continuous but subject to termination by later act of the defendant, I have adopted as the measure of damages the lessened use value of the property while the injury continues," citing the case of Belkus v. Brockton,

Page 272

282 Mass. 285, 288. He found that up to the year 1928 the plaintiff had not suffered any substantial damage from the acts of the defendant, but that beginning with that year and up to the present time the use value of the plaintiff's premises had been lessened as a result of the acts of the defendant in the sum of $50 per annum, and that in addition thereto the damage to the plaintiff's trees, plants and bushes amounted to $75.

The defendant filed four objections to the master's report, the first being for the reason that the second suit was filed while the first suit was pending, and a plea in abatement to that effect was filed by the defendant. The second objection was to the finding that "so far as it is a question of fact it is a natural water course for the reason that this finding is inconsistent with the other findings in the report." The third objection is to "the finding as to the rule of damages ... for the reason that the same is inapplicable in view of the other findings." The fourth objection is to the finding in relation to damages since the year 1928 to the present time for the reason that the last bill of complaint was brought while the first bill was pending and in the first bill there was no request for an assessment of damages.

The record shows that on June 11, 1935, the trial judge made the following order for decrees: that an interlocutory decree be entered overruling the defendant's plea in abatement; that a final decree be entered providing that the defendant be permanently enjoined from obstructing the stream flowing through and over his land, as described in the report of the master, so as to cause the water thereof to back up and overflow the land of the plaintiff; that the plaintiff's damages caused by the obstruction of said stream by the defendant be established in the sum of $425; that the defendant be ordered to pay to the plaintiff said sum; and that the plaintiff be entitled to costs. Thereafter decrees were entered in conformity with the order for decrees previously entered. The defendant appealed.

The question is whether the stream of water which was diverted by the defendant onto the plaintiff's land was a natural watercourse or was mere surface drainage which ran

Page 273

from the defendant's land over the land of the plaintiff. The findings of the master in the twelfth paragraph of his report show that all of the water which eventually ran through the culvert on Jerome Avenue across the defendant's land to the culvert on Belisle Avenue had its source originally as surface water draining from the various hills in the neighborhood, and that none of these streams originated in springs, lakes, ponds or brooks; that the surface water which eventually enters the upper culvert on Jerome Avenue through the most southerly ditch shown on the sketch had, by reason of the contour of the land, formed its own natural channel at a distance of one thousand feet from Jerome Avenue, and has flowed in that natural channel since some time prior to 1891; that this stream has banks and a bed, and is approximately two feet deep and two and one half feet wide; that the surface water which eventually flows in the northerly ditch, and which enters the same culvert on Jerome Avenue, is led to that spot entirely through artificially constructed ditches, drains and culverts and is conducted along Jerome Avenue by artificially constructed catch basins, drain pipes, culverts and ditches; that the channel running through the culvert on the easterly side of Jerome Avenue along and over the line of lot 6 was artificially constructed, "but . . . that prior to the construction of this ditch a stream had made its own bed and banks and passed over substantially the same ground, the ditch apparently having been built to widen and straighten the original course of the stream"; "that this stream which is no longer visible was constructed by the natural flow of all the other waters referred to in this report which converged at the culvert set near the northerly end of lot 6"; that this same stream, after flowing a distance of about one hundred fifty feet northeasterly from Jerome Avenue spread out over a flat area and did not run between well defined banks, and did not have a definite bed, but that subsequently it again narrowed into a well defined natural channel at a point near the beginning of the defendant's present drain pipe; that it flowed through a channel made by its own action across the defendant's land to a point; that there it began to spread out without any well defined

Page 274

channel or banks until it entered the culvert on Belisle Avenue; that the channel from the culvert on the easterly side of Belisle Avenue to the easterly side of the defendant's land ranged in depth from one foot to two feet, and in width from two feet to four feet; and that this was the approximate size of that portion of the channel which has since been covered by the fill. The stream in question was found by the master to be a natural watercourse. We are of opinion that upon the subsidiary findings of the master this finding was warranted. It was said in Luther v. Winnisimmet Co. 9 Cush. 171, at page 174, "that a watercourse is a stream of water, usually flowing in a definite channel, having a bed and sides or banks, and usually discharging itself into some other stream or body of water; that, to constitute a watercourse, the size of the stream was not important, - it might be very small, and the flow of the water need not be constant, - but that it must be something more than a mere surface drainage over the entire face of a tract of land, occasioned by unusual freshets or other extraordinary causes; and it was a question of fact for the jury to determine, upon the evidence before them, whether any such watercourse was proved to have existed." It was said in Ashley v. Wolcott, 11 Cush. 192, at page 195: "To maintain the right to a watercourse or brook, it must be made to appear that the water usually flows in a certain direction, and by a regular channel, with banks or sides. It need not be shown to flow continually; it may be dry at times, but it must have a well defined and substantial existence." See also McGowen v. Carr, 272 Mass. 573; Yaskill v. Thibault, 273 Mass. 266; Gould on Waters (3d ed.) § 263.

The interlocutory decree, overruling the defendant's plea in abatement, and the final decree are affirmed.

Ordered accordingly.