WENDLANDT, J. In this case, we are called on to apply basic principles of contract formation to a nonnegotiable, standard form "terms of use" contract that the defendants Uber Technologies, Inc., and Rasier, LLC (collectively, Uber), presented to the plaintiff, William Good, when he opened Uber's digital mobile platform application (app). The app matches users needing transportation with drivers willing to provide a ride. One of the terms required Good to arbitrate his negligence-based claims against Uber and one of its drivers, the defendant Jonas Yohou.

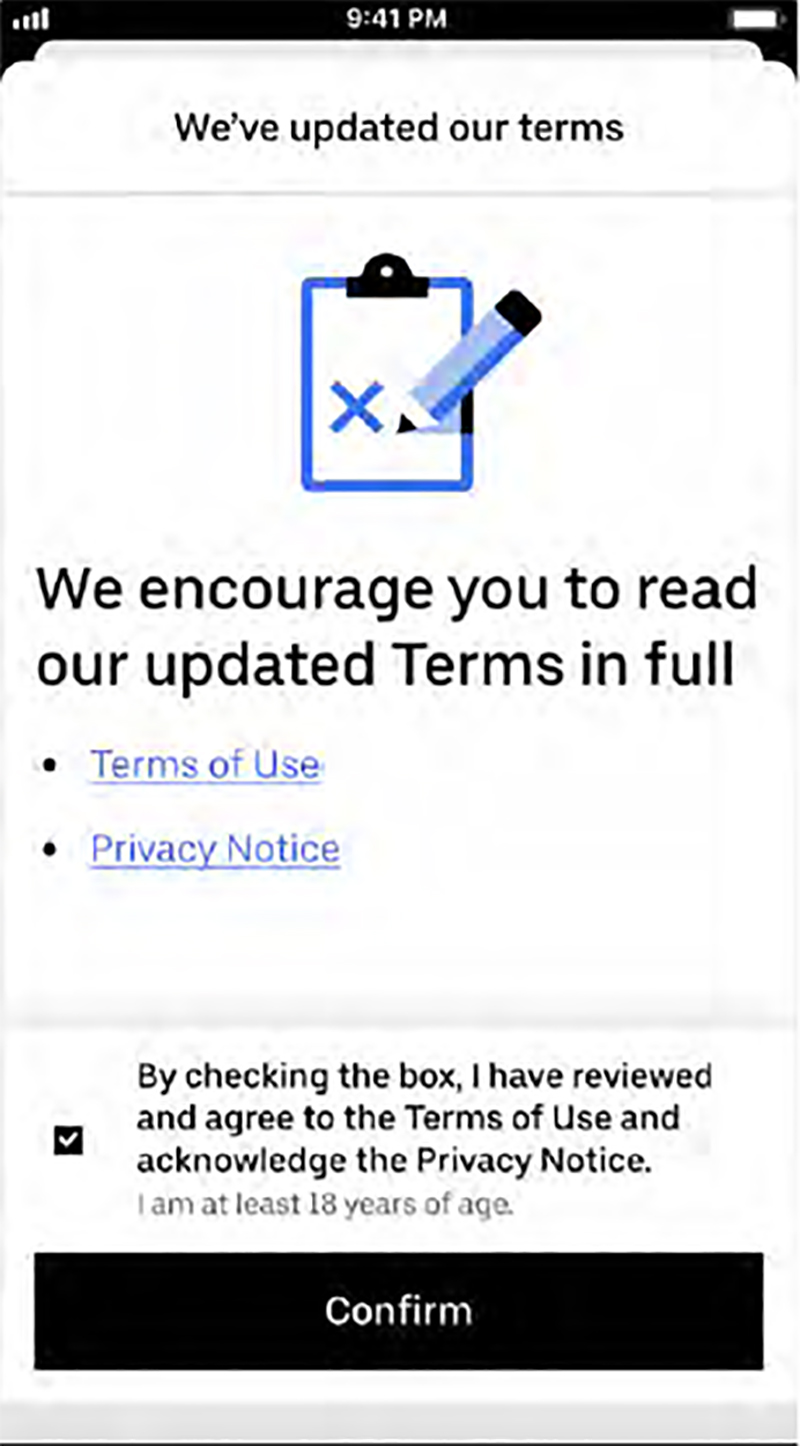

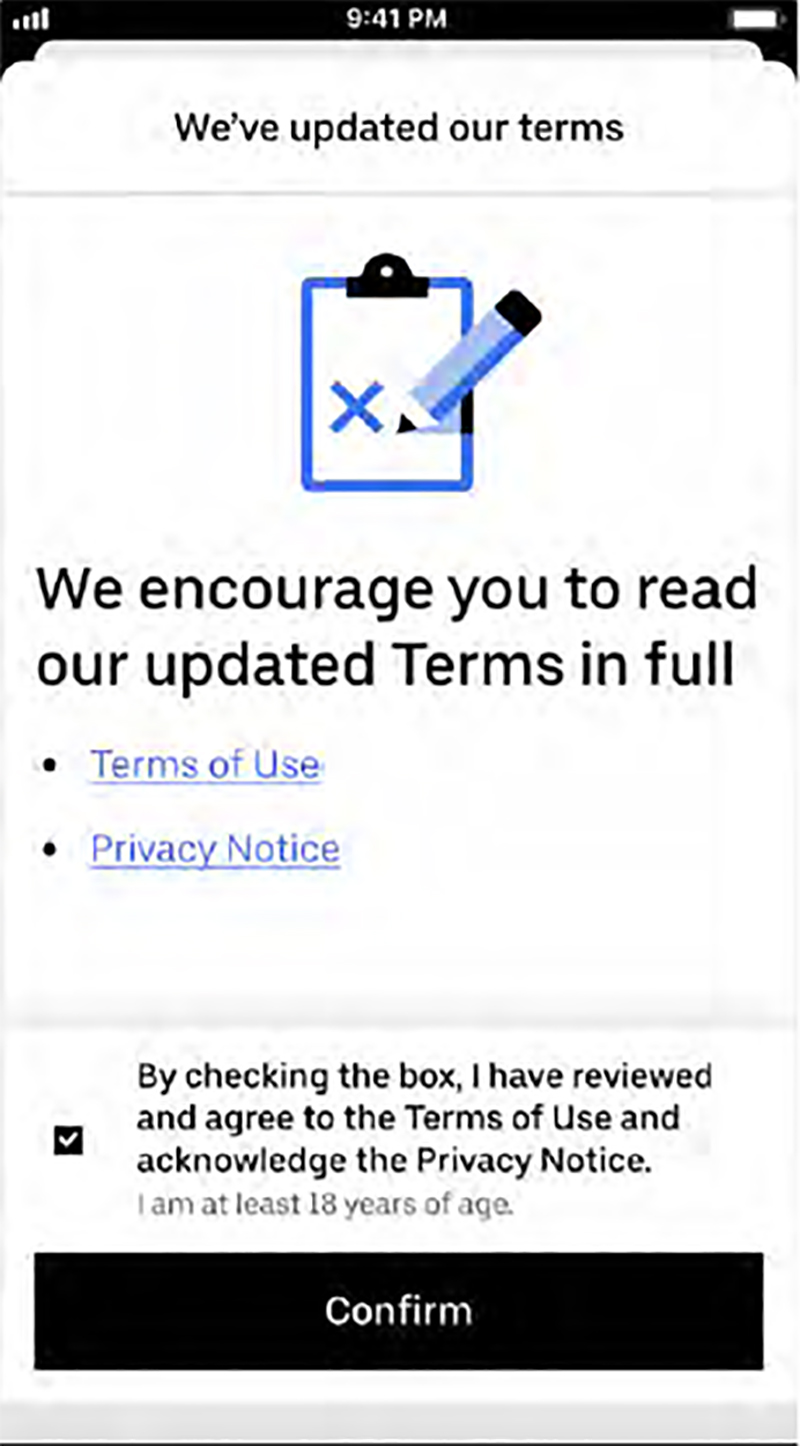

Relevant to this narrow inquiry, Uber presented its terms of use to Good through its app in a manner that prevented Good from continuing to use Uber's services on his cellular telephone unless Good both clicked a checkbox indicating that he had "reviewed and agree[d]" to the terms and activated a button labeled "Confirm," further indicating his assent. This blocking interface included a large graphic image of a clipboard holding a document; near the bottom of the document was an "X" alongside a graphic of a pencil poised as if to sign a legal instrument. The interface was focused and uncluttered; it clearly alerted Good multiple times, in prominent boldfaced text, that the purpose of the blocking screen was to notify Good of Uber's terms of use. It encouraged Good to review those terms and provided an identifiable hyperlink directly to the full text of the terms of use document.

We conclude that these and other features of Uber's "clickwrap" [Note 2] contract formation process put Good on reasonable notice of Uber's terms of use, one of which was the agreement to arbitrate disputes, like the present one, concerning the personal injuries he suffered. Further concluding that Good's selection of the checkbox

Page 118

adjacent to the boldfaced text stating that he "agree[d]" to the terms and his activation of the "Confirm" button reasonably manifested his assent to the terms, we reverse the order of the Superior Court judge denying Uber's motion to compel arbitration, and we remand for entry of an order to submit the claims to arbitration. [Note 3]

1. Background. [Note 4] Uber is a Delaware corporation, registered to do business in the Commonwealth. It maintains an app, which connects individuals seeking transportation with drivers. Yohou was one such driver.

Good, who was a chef at a Boston restaurant, first registered a customer account with Uber in August 2013. On April 25, 2021, when Good opened Uber's app to secure a ride, he was presented with a blocking screen, announcing that Uber had updated its terms of use. Good clicked a checkbox next to text indicating that he had "reviewed and agree[d]" to the terms. Good also activated a button at the bottom of the interface labeled "Confirm." These features are discussed in depth below. Only after performing these actions could Good order a ride.

Five days later, Good again used Uber's app, this time to order a ride from his work in Boston to his home in Somerville. In response, Yohou was dispatched. During the drive, Yohou's car collided with another vehicle. In the ensuing impact, Good was thrust forward and hit his head on the front passenger's seat headrest, breaking his neck. Good instantly was paralyzed and later was diagnosed with a severe spinal injury and quadriplegia.

a. Blocking screen. On April 25, 2021, when Good opened Uber's app on his cellular telephone, he received the following "in-app blocking pop-up screen," displayed infra, that covered nearly the entire footprint of his device's display; this interface blocked further access to, and use of, Uber's app.

Page 119

As shown, set against a largely white-colored background, at the top of the pop-up screen, text written in black, boldfaced, medium-sized [Note 5] font stated, "We've updated our terms." Underneath the text, below a faint, gray line, the screen displayed a large image of a blue rectangle with a black clipping element, indicative of a clipboard. The clipboard was shown holding a white rectangular shape reminiscent of a sheet of paper with a blue-colored, prominent "X" on its lower left corner; adjacent to the "X" was an image of a pencil positioned diagonally to suggest its use for writing. The image, which in view of these features

Page 120

suggested the execution of a legal instrument, was centered horizontally in the top third of the screen and was the single largest item on the screen.

Below the image, at approximately the vertical center of the interface, and in larger, boldfaced, black lettering, the screen stated, "We encourage you to read our updated Terms in full." As set forth, the word "Terms" was capitalized. The statement spanned two lines with the new line beginning between the words "read" and "our," such that the words "updated Terms" were centered on the screen. Immediately below this statement were two black bullet points, each adjacent to medium-sized text, which was underlined and colored blue. The first bullet point stated, "Terms of Use," and the second stated, "Privacy Notice." Each was a hyperlink that, if activated by clicking on it, presented the user with the full text of Uber's terms of use and privacy notice, respectively.

On the bottom third of the screen, beneath a faint, gray line, was a checkable box. The box was centered next to two statements. The first statement was shown in medium-sized, black, boldfaced font and stated, "By checking the box, I have reviewed and agree to the Terms of Use and acknowledge the Privacy Notice." As shown, the words "Terms," "Use," and "Privacy Notice" each were capitalized. The statement spanned three lines with the second line beginning between the words "reviewed" and "and agree" and the third line beginning between the words "and" and "acknowledge." The checkbox was centered between the second and third lines of this first statement. The second statement was shown just below the first; it was written in faint, gray-colored, noticeably smaller font and stated, "I am at least 18 years of age."

At the bottom of the screen, underneath the checkbox and accompanying text, a large black bar stretched across most of the display's width. Centered in the bar, which resembled, and thus was suggestive of, a mechanical push button, white medium-sized text stated, "Confirm."

As the name suggests, the blocking screen prevented the user from using the app. To proceed past the screen, the user was required to engage in two actions. First, the user had to check the box adjacent to the text indicating that the user had "reviewed and agree[d]" to the terms of use and the smaller text indicating that the user was at least eighteen years old; second, the user had to click the large button stating "Confirm." The user was not required to click on the hyperlinks to proceed and thus was not

Page 121

required actually to review either the terms of use document or the privacy notice discussed infra.

When Good was presented with this screen, he checked the checkbox and clicked the "Confirm" button. The record does not reflect whether Good either activated the hyperlink that opened the contents of Uber's terms of use or reviewed those terms. Good has no specific recollection of doing so.

b. Uber's terms of use. The terms of use document, accessible from the interface via the hyperlink discussed supra, comprised a nonnegotiable contract of adhesion. [Note 6] As the name suggested, the document set forth Uber's terms for using its services. It was comprehensive in scope, covering topics such as the nature of the relationship between Uber and the user, dispute resolution, user conduct expectations, ownership of intellectual property, payment procedures, choice of law, disclaimers, limitation of liability, indemnification, and forum selection.

The first section of the document, entitled "Contractual Relationship," established that the terms of use "govern" a user's access to and use of Uber's services, that the terms "CONSTITUTE A LEGAL AGREEMENT BETWEEN [THE USER] AND UBER," and that the terms superseded any prior agreements between the user and Uber, with limited exceptions. Pertinent here, the fifth full paragraph of the first section called the reader's attention, in all-capitalized, boldfaced letters, to an "IMPORTANT" warning that the terms included an "ARBITRATION AGREEMENT," requiring the user to resolve "ALL DISPUTES" with Uber, with limited exceptions, [Note 7] through "FINAL AND BINDING ARBITRATION." [Note 8] The paragraph concluded by

Page 122

requiring users to acknowledge that they have "TAKEN TIME TO CONSIDER THE CONSEQUENCES OF THIS IMPORTANT DECISION." [Note 9] The first section ended with a reference to Uber's "Privacy Notice," which governed Uber's collection and use of personal information in connection with its services. As discussed infra, the privacy notice also was noted in the interface, which provided a hyperlink thereto.

The terms of use's second section, entitled "Arbitration Agreement," set forth a requirement to submit claims, including personal injury claims "arising out of or relating to . . . accidents," to arbitration. The arbitration agreement further waived the right to a trial by jury or to bring or to participate in a class, or other representative, action. [Note 10]

The section delineated the exclusive authority of the arbitrator

Page 123

"to resolve any disputes relating to the interpretation, applicability, enforceability or formation of this Arbitration Agreement, including any claim that all or any part of this Arbitration Agreement is void or voidable. The Arbitrator shall also be responsible for determining all threshold arbitrability issues, including issues relating to whether the Terms are applicable, unconscionable or illusory and any defense to arbitration, including waiver, delay, laches, or estoppel. If there is a dispute about whether this Arbitration Agreement can be enforced or applies to a dispute, [the user] and Uber agree that the arbitrator will decide that issue."

The section provided that the arbitration agreement was governed by the Arbitration Act (FAA), 9 U.S.C. §§ 1 et seq. [Note 11]

The third section of the terms stated in all capitalized letters that Uber was not a "PROVIDER OF TRANSPORTATION," and that "DRIVERS ARE NOT ACTUAL AGENTS, APPARENT AGENTS, OSTENSIBLE AGENTS, OR EMPLOYEES OF UBER IN ANY WAY." This latter statement appeared multiple times in the terms.

The sixth section of the terms set forth Uber's disclaimer of all representations and warranties, express, implied, or statutory. It stated that "UBER DOES NOT CONTROL, MANAGE OR DIRECT . . . DRIVERS." This section also provided that

"UBER SHALL NOT BE LIABLE FOR INDIRECT, INCIDENTAL, SPECIAL, EXEMPLARY, PUNITIVE, OR CONSEQUENTIAL DAMAGES, INCLUDING LOST PROFITS, LOST DATA, PERSONAL INJURY, OR PROPERTY DAMAGE RELATED TO, IN CONNECTION WITH, OR OTHERWISE RESULTING FROM ANY USE OF THE SERVICES, REGARDLESS OF THE NEGLIGENCE (EITHER ACTIVE, AFFIRMATIVE, SOLE, OR CONCURRENT) OF UBER, EVEN IF UBER HAS BEEN ADVISED OF THE POSSIBILITY OF SUCH DAMAGES." [Note 12]

Page 124

That same section of the terms also provided an indemnification provision in favor of Uber.

2. Prior proceedings. In January 2022, Good commenced this action in the Superior Court against Uber and Yohou, alleging negligence and seeking damages for the injuries he suffered in the crash. [Note 13] The defendants filed a joint motion to compel arbitration, pursuant to G. L. c. 251, § 2, [Note 14] contending that the terms of use bound Good to pursue his claim only through arbitration. In opposition, Good asserted that a contract was not formed because Good neither had reasonable notice of Uber's terms of use nor had manifested assent to the terms. The motion judge agreed and denied the motion.

The defendants timely appealed, and we transferred the case to this court on our own motion.

3. Discussion. We review a denial of a motion to compel arbitration de novo. Archer v. Grubhub, Inc., 490 Mass. 352, 355 (2022). Such motions generally are treated as motions for

Page 125

summary judgment. [Note 15] Miller v. Cotter, 448 Mass. 671, 676 (2007). Accordingly, the party seeking to enforce the arbitration provision bears the burden of proving that the parties entered into an agreement to arbitrate disputes. Kauders v. Uber Techs., Inc., 486 Mass. 557, 572 (2021). In conducting our review, we construe all facts in favor of the nonmoving party. See Miller, supra ("judge correctly treated . . . defendants' motion to compel arbitration as one for summary judgment," and "[w]e review a grant of summary judgment de novo, construing all facts in favor of the nonmoving party").

"Congress enacted the FAA in response to widespread judicial hostility to arbitration." American Express Co. v. Italian Colors Restaurant, 570 U.S. 228, 232 (2013) (Italian Colors). This hostility included a "paternalistic attitude" prevalent among some judges that "only they could ensure that individual plaintiffs would be afforded a fair opportunity to challenge corporate defendants." Broome, An Unconscionable Application of the Unconscionability Doctrine: How the California Courts Are Circumventing the Federal Arbitration Act, 3 Hastings Bus. L.J. 39, 42 (2006). Indeed, "[i]n many jurisdictions, courts once viewed agreements to arbitrate as a 'lesser caste' of contract provisions that could be ignored with impunity." Stipanowich, Punitive Damages and the Consumerization of Arbitration, 92 Nw. U. L. Rev. 1, 6 (1997).

Enacted in response to this hostility and to quash the notion that only a judge could ensure a fair hearing, the FAA embodies a "liberal federal policy favoring arbitration" (citation omitted). AT&T Mobility LLC v. Concepcion, 563 U.S. 333, 339 (2011). Massachusetts's counterpart, the Massachusetts Arbitration Act (MAA), G. L. c. 251, §§ 1 et seq., likewise "expresses a strong public policy favoring arbitration." Miller, 448 Mass. at 676, quoting Home Gas Corp. of Mass., Inc. v. Walter's of Hadley, Inc., 403 Mass. 772, 774 (1989). The FAA and our State counterpart require "courts 'rigorously' to 'enforce arbitration agreements according to their terms.'" Epic Sys. Corp. v. Lewis, 584 U.S. 497, 506 (2018), quoting Italian Colors, 570 U.S. at 233. See Miller, supra.

Page 126

Ultimately, "[t]he FAA reflects the fundamental principle that arbitration is a matter of contract." Rent-A-Center, W., Inc. v. Jackson, 561 U.S. 63, 67 (2010) (Rent-A-Center). Thus, whether parties have agreed to arbitrate their disputes is governed by ordinary State law contract principles. Kauders, 486 Mass. at 571. First Options of Chicago, Inc. v. Kaplan, 514 U.S. 938, 944 (1995) ("When deciding whether the parties agreed to arbitrate a certain matter . . . courts generally . . . apply ordinary [S]tate-law principles that govern the formation of contracts"). Kindred Nursing Ctrs. Ltd. Partnership v. Clark, 581 U.S. 246, 251 (2017) ("generally applicable contract" principles govern whether parties have agreed to arbitration [citation omitted]). Both the FAA and the MAA "establish[] an equal-treatment principle," precluding any rule "discriminating . . . against arbitration." Id. See Miller, 448 Mass. at 677.

Therefore, in determining whether the notice and reasonable assent requirements of contract formation are met, we approach an agreement that includes an arbitration provision in the same manner as we would any other provision: the party seeking to enforce an agreement to arbitrate must demonstrate both offer and acceptance. See, e.g., Battle v. Howard, 489 Mass. 480, 492 (2022), citing McCarthy v. Tobin, 429 Mass. 84, 86 (1999) (contract requires accepted offer); Canney v. New England Tel. & Tel. Co., 353 Mass. 158, 164 (1967) (burden on proponent).

In the context of a nonnegotiable standard form contract, to show that a contract in fact was formed, "there must be both . . . notice of the terms [of the contractual offer] and a reasonable manifestation of assent to those terms [so as to constitute acceptance of the offer]." Kauders, 486 Mass. at 572. While the dissent now chides the court for failing to alter fundamentally the principles of contract formation under the auspices of developing the "common law," post at 147-148, we have concluded recently and unanimously that "the fundamentals of online contract formation should not be different from ordinary contract formation." Kauders, supra at 571. "The touchscreens of Internet contract law must reflect the touchstones of regular contract law," we explained (emphasis added). Id. Of course, that does not mean that our approach is static or unadaptable to new technologies; for example, as discussed infra, we have emphasized the need, tailored to the unique circumstances of mobile app-based transactions, for a clear interface to govern the reasonable notice inquiry. See id.

Page 127

a. Notice of the offer. With these principles in mind, we turn to the issue whether Uber provided Good with notice of the terms of the contractual offer. The notice element can be satisfied in two ways. First, "[w]here the offeree has actual notice of the terms, [the notice] prong is satisfied without further inquiry." Kauders, 486 Mass. at 572. "Actual notice will exist where the [offeree] has reviewed the terms." Archer, 490 Mass. at 361, quoting Kauders, supra. Actual notice "will also generally be found where the user must somehow interact with the terms before agreeing to them," including by scrolling through them. Kauders, supra.

Second, "[a]bsent actual notice, the totality of the circumstances must be evaluated [to] determin[e] whether reasonable notice has been given of the terms." Kauders, 486 Mass. at 573. "Reasonable notice of a contract's terms [may] exist[] even if the party did not actually view the agreement, so long as the party had an adequate opportunity to do so." Archer, 490 Mass. at 361.

i. Actual notice. Uber contends Good had actual notice of the terms because the record reflects that Good clicked the checkbox on Uber's interface adjacent to text stating, "By checking the box, I have reviewed and agree to the Terms of Use . . . ." We disagree. [Note 16]

Checking a box next to the statement that he reviewed the terms is not equivalent to an admission by Good that he, in fact, reviewed the terms of use, or even scrolled through them. See Mass. R. Civ. P. 36, 365 Mass. 795 (1974). Cf. Sgouros v. TransUnion Corp., 817 F.3d 1029, 1035 (7th Cir. 2016) ("we cannot presume that a person who clicks on a box that appears on a computer screen has notice of all contents not only of that page but of other content that requires further action [scrolling, following a link, etc.]"). It is entirely plausible, indeed likely, that Good did not review the terms. Uber's interface did not require Good to click on

the hyperlink to the terms themselves. While Uber has provided computer logs showing that Good checked the box, it has not provided any similar logs to suggest he followed

Page 128

the hyperlink to the terms themselves. We previously have noted empirical studies showing that most users of mobile applications "do not read the terms of use." [Note 17] Kauders, 486 Mass. at 577. See Ayres & Schwartz, The No-Reading Problem in Consumer Contract Law, 66 Stan. L. Rev. 545, 547-548 (2014) (describing empirical evidence showing number of consumers who read terms is "miniscule"). See also Conroy & Shope, Look Before You Click: The Enforceability of Website and Smartphone App Terms and Conditions, 63 Boston B.J. 23, 23 (Spring 2019) ("Most users will not have read the terms . . .").

Accordingly, in the absence of record evidence that Good accessed the terms of use through the hyperlink or "somehow interact[ed] with the terms before agreeing to them," Uber has not met its burden to show actual notice. Kauders, 486 Mass. at 572.

ii. Reasonable notice. We next consider whether Uber provided reasonable notice of the terms of use. See Kauders, 486 Mass. at 573. In doing so, we "evaluate 'the totality of the circumstances.'" Archer, 490 Mass. at 361, quoting Kauders, supra. We consider, inter alia, "the nature, including the size, of the transaction," "the interface by which the terms are being communicated," "the form of the contract," and "whether the notice conveys the full scope of the terms and conditions." Kauders, supra. "Ultimately, the offeror must reasonably notify the user that there are terms to which the user will be bound and give the user the opportunity to review those terms" (emphasis added). [Note 18] Id.

A. Nature and size of the transaction. "The full context of any transaction is critical to determining whether any particular notice is sufficient to put a consumer on . . . notice of contractual terms contained on a separate, hyperlinked page." Sellers v. JustAnswer LLC, 73 Cal. App. 5th 444, 453 (2021). The nature of the transaction is viewed from the perspective of "reasonable people

Page 129

in the position of the parties." Meyer v. Uber Techs., Inc., 868 F.3d 66, 77 (2d Cir. 2017), quoting Schnabel v. Trilegiant Corp., 697 F.3d 110, 124 (2d Cir. 2012).

The transaction giving rise to the present action involved using Uber's app to secure a ride, an action in which presumably Good had engaged numerous times between 2013, when he first registered an account with Uber, and 2021, when he was presented with the terms of use at issue here. In this context, Good may not have expected to be entering a contract at all, let alone a contract comprising the comprehensive set of terms offered by Uber. But see Meyer, 868 F.3d at 77 (warning against presumption that "the user has never before encountered an app or entered into a contract using a smartphone").

Moreover, the presumably modest price of purchasing a single local ride also might have lulled Good into believing that his use of Uber's service would not be accompanied by extensive contractual conditions. The circumstances giving rise to Good's activation of the app to secure transportation certainly would not call upon the reasonably prudent consumer to believe that the advice of an attorney was required or even to suggest such advice might be beneficial. [Note 19] Contrast H1 Lincoln, Inc. v. South Washington St., LLC, 489 Mass. 1 (2022) (commercial transaction by sophisticated parties represented by counsel).

B. Interface and form of the contract. Where the nature of the transaction is such that a reasonably prudent consumer may proceed without realizing that she is also agreeing to a set of comprehensive contractual terms, a particular onus is placed on the offeror to ensure that the interface is designed to disabuse the user of that notion and to put the user on reasonable notice of the terms. Moreover, especially where there is no face-to-face transaction between the contracting parties, it is imperative that the interface convey to the user that a contract is being presented. See, e.g., Kauders, 486 Mass. at 573, citing Polonsky v. Union

Page 130

Fed. Sav. & Loan Ass'n, 334 Mass. 697, 701 (1956) ("terms may not be enforceable where document containing or presenting terms to offeree does not appear to be contract"); Sgouros, 817 F.3d at 1035 ("a person using the Internet may not realize that she is agreeing to a contract at all"). Thus, we examine the interface carefully to determine whether it "reasonably focused" the otherwise unsuspecting user "on the terms and conditions" being imposed, Kauders, supra at 575-576; "[f]or Internet transactions, the specifics and subtleties of the 'design and content of the relevant interface' are especially relevant," Id. at 573, quoting Meyer, 868 F.3d at 75. We ask whether the interface presented the terms in a manner that to a reasonable person in the user's circumstance would "appear to be [a] contract." Kauders, supra, citing Polonsky, supra.

We "evaluate the clarity and simplicity of the communication of the terms." Kauders, 486 Mass. at 573. In doing so, we consider the language used to notify the user of the terms, the prominence with which the hyperlink, if any, to the terms was displayed, and the clarity and extensiveness of the process to access the terms, along with "any other information that would bear on the reasonableness of [the] communicati[on of the terms]." Id., quoting Cullinane v. Uber Techs., Inc., 893 F.3d 53, 62 (1st Cir. 2018). "This is an objective test: the sufficiency of the notice turns on whether, under the totality of the circumstances, [the] communication would have provided a reasonably prudent [user] notice of the [terms being offered, including the arbitration provision]." Archer, 490 Mass. at 362, quoting Bekele v. Lyft, Inc., 199 F. Supp. 3d 284, 295 (D. Mass. 2016), aff'd, 918 F.3d 181 (1st Cir. 2019).

Here, despite the nature of the transaction and the electronic, online presentation, Uber's interface focused the reasonably prudent consumer on the terms being offered by Uber for the continued use of its services. The interface unequivocally and transparently communicated to such a consumer that by checking the checkbox and clicking "Confirm" on the blocking pop-up screen, the user was agreeing to Uber's terms of use.

Specifically, the blocking pop-up screen referenced the terms of use four times -- at the top, twice in the center, and at the bottom of the screen. See Wu v. Uber Techs., Inc., 78 Misc. 3d 551, 556-557, 589-590 (N.Y. Sup. Ct. 2022), aff'd, 219 A.D.3d 1208 (N.Y. 2023) (examining materially identical interface and concluding reasonable notice given in view of uncluttered

Page 131

interface's reference to Uber's terms four times). Contrast Kauders, 486 Mass. at 559-561 (no reasonable notice where reference to terms of use was displayed only once, at bottom of final screen, which itself focused on user's payment information, of three-screen registration process). Uber's display clearly and expressly stated: "We've updated our terms" and "We encourage you to read our updated Terms in full." [Note 20] This text was set forth in prominent typeface; the latter occupied the middle of the screen and used a font size that was larger than any other shown on the screen.

The link to the terms of use was not buried on a cluttered screen or presented inconspicuously at the tail end of a cumbersome registration and payment process. See Meyer, 868 F.3d at 78, 79 (conspicuous notice provided where interface was "uncluttered"); Mallh vs. Showtime Networks Inc., U.S. Dist. Ct., No. 17-cv-6549 (S.D.N.Y. Nov. 7, 2017) ("page was uncluttered and dedicated to the steps required to transact the purchase" and "did not contain any [extraneous] photos or links to promotional material"). The interface addressed only the terms of use and

Page 132

accompanying privacy notice. [Note 21] Nothing distracted from the interface's singular focus on providing notice of, and obtaining assent to, the terms of use, along with acknowledgment of the privacy notice. Contrast Kauders, 486 Mass. at 560-561, 578 (hyperlink to terms obscured within screen focused on payment information); Cullinane, 893 F.3d at 63 ("Other similarly displayed [content] presented simultaneously to the user . . . diminished the conspicuousness of the 'Terms of Service & Privacy Policy' hyperlink").

The interface both "encourage[d]" the user to review the terms of use and provided a hyperlink labeled "Terms of Use." See Sgouros, 817 F.3d at 1035 ("Where the terms . . . must be brought up by using a hyperlink, courts . . . have looked for a clear prompt directing the user to read them"). And it stated, "By checking the box, I have reviewed and agree to the Terms of Use . . . ." [Note 22] "Requiring a user to expressly and affirmatively assent to the terms, such as by indicating 'I Agree' or its equivalent, . . . puts the user on notice that the user is entering into a contractual arrangement." [Note 23] Kauders, 486 Mass. at 574.

The interface also alerted the otherwise unsuspecting user that a contract was being formed by displaying a large pictorial

Page 133

representation of signing a contract; specifically, a graphic of a clipboard holding a document marked by an "X" alongside a pencil poised to sign it. Such an illustration meaningfully conveyed that the user was being presented with a legal document to execute. See Cullinane, 893 F.3d at 62 (use of symbols can help make terms conspicuous). [Note 24] The large graphic portraying a legal document with a pencil poised to sign at the "X" would evoke in the mind of the reasonable consumer the "solemnity of physically signing a written contract." Kauders, 486 Mass. at 574. See Moringiello, Signals, Assent and Internet Contracting, 57 Rutgers L. Rev. 1307, 1316 (2005) ("In contract law, a written signature provides the traditional evidence of assent because when we are asked to sign something, we are conditioned to think that we are doing something important").

The interface also clearly conveyed that the terms were readily available through a hyperlink, which was underlined, written in blue text, and placed in the center of the screen. The clickable link, which provided the user with direct access to the terms, was displayed with "the common appearance of a hyperlink." Cullinane, 893 F.3d at 63 ("hyperlinks . . . are commonly blue and underlined" [quotation and citation omitted]). See Adelson v. Harris, 774 F.3d 803, 808 (2d Cir. 2014) ("being embedded in blue, underlined text" is "the customary manner" of displaying hyperlinks); Fteja v. Facebook, Inc., 841 F. Supp. 2d 829, 835 (S.D.N.Y. 2012), quoting United States v. Hair, 178 Fed. Appx. 879, 882 n.3 (11th Cir. 2006), cert. denied, 549 U.S. 1140 (2007) (underlining text indicates that it is hyperlink that "sends users who click on it directly to a new location"). Contrast Sarchi v. Uber Techs., Inc., 2022 ME 8, ¶ 35 ("lack of underlining and the muted gray coloring . . . mean[t] that [link to terms was] not

Page 134

obviously identifiable as a hyperlink").

One simple click on the hyperlink directed the user to the full text of the terms of use document, which stated at the top, "Contractual Relationship"; no additional steps were required. [Note 25] See Kauders, 486 Mass. at 573, citing Cullinane, 893 F.3d at 62 (noting that number of steps required to access terms is factor in determining reasonableness of notice). The first paragraph of the terms of use stated that the terms "CONSTITUTE A LEGAL AGREEMENT BETWEEN YOU AND UBER." Within the first five paragraphs, a warning alerted the user "THAT THIS AGREEMENT CONTAINS PROVISIONS THAT GOVERN HOW CLAIMS BETWEEN YOU AND UBER CAN BE BROUGHT, INCLUDING THE ARBITRATION AGREEMENT." The very next section, titled "Arbitration Agreement," set forth those provisions. Thus, within the terms of use document itself, the binding arbitration agreement was apparent. See Wu, 78 Misc. 3d at 589 (concluding with respect to materially identical version of Uber's terms: "The arbitration agreement, in short, is not hidden or disguised; rather, it is clear and conspicuous such that a prudent user would be on notice of it").

Critically, the interface -- an "in-app blocking pop-up screen" -- prevented the user from proceeding to order a ride using Uber's services without first interacting with the interface. [Note 26] It interrupted the user, who likely was distracted by the singular goal of obtaining immediate transportation, and forced the user to attend to the information conveyed on the screen. [Note 27] At a minimum,

Page 135

the interface required the user to skim the screen to identify the box adjacent to the medium-sized boldfaced text stating, "By checking the box, I have reviewed and agree to the Terms of Use . . . ," to check the box, and then to press the "Confirm" button in order to proceed. [Note 28] Even such a cursory review of the interface would have alerted the reasonably prudent user that a contract was being offered, that its terms were readily available through the hyperlink, and that assent thereto was required in

Page 136

order to continue to use Uber's app. [Note 29]

Good's argument that the interface must require the user to open or scroll through the terms of use for the interface to comply with the reasonable notice requirement confuses reasonable notice with actual notice. [Note 30] See post at note 16; Kauders, 486 Mass. at 572-573 (notice requirement satisfied through actual notice or reasonable notice). Actual notice requires that the user interact with or scroll through the terms. Kauders, supra at 572. Reasonable notice does not; instead, reasonable notice suffices where the totality of the circumstances provides the reasonably prudent user with information sufficient to understand that terms of use are being offered and makes those terms readily available for the user to access. See Archer, 490 Mass. at 361-362. We do not require, for purposes of reasonable notice, that the user actually scroll through the terms. [Note 31] See Kauders, supra at 574 (clickwrap

Page 137

agreements "are regularly enforced"); Emmanuel v. Handy Techs., Inc., 992 F.3d 1, 9 (1st Cir. 2021) ("we are not aware" of "any precedent . . . that would indicate that Massachusetts law imposes . . . a requirement" that user scroll through terms of use); Covino v. Spirit Airlines, Inc., 406 F. Supp. 3d 147, 152 (D. Mass. 2019) ("courts in this Circuit are in near universal agreement that clickwrap contracts are enforceable").

That Uber may use a marginally different contracting process for onboarding drivers is neither dispositive nor surprising. Entering a relationship for one's livelihood typically is far more consequential than seeking a ride.

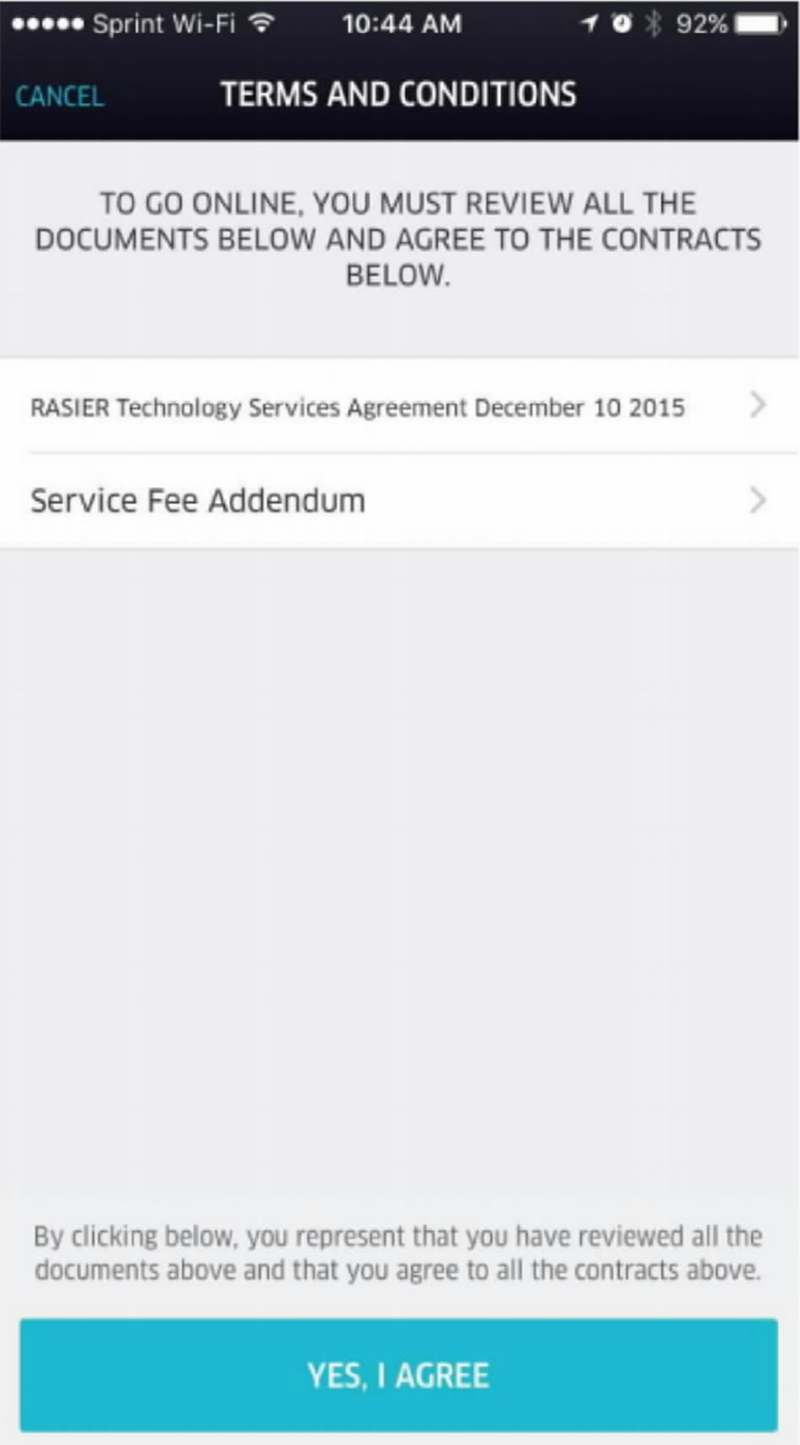

In any event, the user interface that Uber employed with Good bears a striking similarity to the interface that it used with drivers and that we previously cited approvingly. See Kauders, 486 Mass. at 576-577 (describing Uber's driver app as presenting prospective driver with blocking screen with hyperlink to terms, requiring driver to click "I AGREE" to confirm that driver had reviewed and accepted terms, and requiring driver to "confirm" same for second time). Indeed, the driver interface addressed in Capriole vs. Uber Techs., Inc., U.S. Dist. Ct., No. 1:19-CV-19941 (D. Mass. Mar. 31, 2020), and reproduced below, which in Kauders we approvingly presented as an exemplar of reasonable notice of the terms and conditions of Uber's agreement with drivers, including a term requiring arbitration, is nearly identical in all material respects to the user interface at issue here. See Kauders, supra at 577, 580.

Page 138

| Driver Interface Providing Reasonable Notice of Arbitration Agreement |

User Interface |

|

|

As with the present interface, the driver interface, displayed supra, directed drivers to review the terms and provided hyperlinks to the same. See Capriole, supra. It then required drivers to click a button stating, "YES I AGREE" following a statement in font size much smaller than the one used for the user interface, which stated, "By clicking below, you represent that you have reviewed all the documents above and that you agree to all the contracts above." Id. The interface required drivers to "CONFIRM" that they had reviewed and agreed to those terms. Id. Aside from marginally different language, the driver interface does not differ materially from Uber's current user interface. In Kauders, we approved of the driver interface as providing reasonable notice requiring arbitration even though it did not require review of the terms; did not display any of the terms themselves, instead making them available through a hyperlink that was less prominent than the one used in the user interface; included hyperlinks to two separate agreements; used the terms "I agree" and "Confirm"; and did not highlight particular terms, including the requirement of arbitration, that might later be determined to

Page 139

be unconscionable. See id.

C. Full scope of terms. Finally, we consider whether Uber's "notice convey[ed] the full scope of the terms and conditions." Kauders, 486 Mass. at 573. As discussed supra, the interface expressly communicated that Uber was presenting its terms of use. The interface then conspicuously linked to those terms of use, making "readily available" the entirety of the terms to which the user would be bound upon indicating assent. See id. (we consider whether notice makes terms readily available). See also Archer, 490 Mass. at 354, 361-362 (reasonable notice given where terms were available through hyperlink). [Note 32]

Because Uber's interface sufficiently "focused the user on the terms and conditions," thereby "notify[ing] the user that there are terms to which the user will be bound," and made those terms readily available, "giv[ing] the user the opportunity to review those terms," reasonable notice was conveyed (emphasis added). [Note 33]

Page 140

Kauders, 486 Mass. at 573, 576. See Meyer, 868 F.3d at 79 ("While it may be the case that many users will not bother reading the additional terms, that is the choice the user makes; the user is still on . . . notice"). Contrast Specht v. Netscape Communications Corp., 306 F.3d 17, 31 (2d Cir. 2002) (offer "did not carry an immediately visible notice of the existence of license terms or require unambiguous manifestation of assent to those terms").

The dissent's position notwithstanding, reasonable notice does not demand that the offeror highlight particular provisions of the terms of use where, as here, the interface provides a readily identifiable hyperlink to all of the terms, none of which was buried in fine print. [Note 34] See discussion supra. Instead, the offeror can either "require the user to open the terms or make them readily available" (emphasis added). Kauders, 486 Mass. at 573. Ultimately, reasonable notice requires that an offeror "reasonably notify the user that there are terms to which the user will be bound and give the user the opportunity to review those terms" (emphases added). Id. Indeed, we have acknowledged that a prominently displayed statement explaining the connection between creating an account and agreeing to Uber's terms of use "would encourage opening and reviewing the terms." Id. at 578. Unlike Uber's prior user interface, which we determined did not provide reasonable notice, the present one expressly "encourage[d]" the user to open the hyperlink to the terms of use, "prominently" displayed that hyperlink, and made clear that use

Page 141

of the app was conditioned on agreement to those terms. Id. at 559-562, 573.

Moreover, demanding that the offeror highlight particular terms, even if one could agree as to which terms to highlight, ignores the well-established and widely recognized principle that offerees have a duty to read the terms of a contract to which they assent and are not excused from a contract's terms solely by virtue of having chosen not to do so. [Note 35] See Haufler v. Zotos, 446 Mass. 489, 501 (2006), quoting Wilkisius v. Sheehan, 258 Mass. 240, 243 (1927) ("The general rule is, that, in the absence of fraud, one who signs a written agreement is bound by its terms whether he reads and understands it or not"); Grace v. Adams, 100 Mass. 505, 507 (1868) ("It was [the offeree's] duty to read [the contract]. The law presumes, in the absence of fraud or imposition, that he did read it, or was otherwise informed of its contents, and was willing to assent to its terms without reading it"); Restatement (Second) of Contracts § 23 comment e (1981) ("An offeree, knowing that an offer has been made to him, need not know all its terms. Knowing that an offer has been made, he can accept without investigation of the exact terms, either intentionally or by words or conduct creating an unintended appearance of intention to accept"). [Note 36] This same principle applies to

Page 142

standard form contracts. [Note 37]

As discussed supra, Uber's interface provided a clearly identifiable hyperlink to the terms of use document. That Good chose not to read the terms of use document made readily accessible to him does not detract from the reasonableness of the notice provided. See Archer, 490 Mass. at 361-363.

b. Reasonable manifestation of assent. We turn next to the question whether Good reasonably manifested assent to the terms. See Kauders, 486 Mass. at 572. In evaluating whether assent was obtained, "we consider the specific actions required to manifest assent." Id. at 573-574. "The connection between the action [that manifests assent] and the terms [should be] direct [and] unambiguous." Id. at 580. See, e.g., Archer, 490 Mass. at 362-363 (use of "and/or" in signature line stating plaintiffs "read, understand, and/or agree to be bound by the terms" not so "indirect or ambiguous that the agreement cannot be enforced").

Page 143

Where a user is "required to expressly and affirmatively manifest assent to an online agreement by clicking or checking a box that states that the user agrees to the terms and conditions," such "'clickwrap' agreements . . . are regularly enforced." Kauders, 486 Mass. at 574. See Gaker v. Citizens Disability, LLC, 654 F. Supp. 3d 66, 76 (D. Mass. 2023) ("'clickwrap' agreement[s] . . . carry a degree of presumption of validity"). Clicking a box to indicate assent provides "an action comparable to the solemnity of physically signing a written contract," by "help[ing] alert users to the significance of their actions." Kauders, supra at 574-575. Thus, "[w]here [users] so act, they have reasonably manifested their assent." Id. at 575.

Here, the interface required Good to affirmatively manifest his assent twice. He was required to check a box immediately adjacent to text stating, "By checking the box, I have reviewed and agree to the Terms of Use . . . ." Thereafter, he was required to activate a button stating "Confirm." This connection between checking the box and indicating assent to the terms was express and unambiguous, particularly as Good could not proceed past the screen without so indicating his assent. [Note 38]

Good contends that by presenting the blocking screen at the moment he intended to use Uber's services to secure a ride, Uber failed to provide him with a meaningful opportunity to review the terms. We disagree. Arguably, the moment a user wants to use the services may be the time when the user is most likely to focus on the terms and to determine whether to abide by them or to take one's business elsewhere. In any event, the interface did not contain a limited time frame governing Good's consideration of the terms; presumably, he could have taken as long as he desired to review the terms. During that time, he could have considered other available means of transportation, including obtaining transportation from another ride share app, a taxicab, or public transportation. [Note 39] In these circumstances, we conclude that Good

Page 144

reasonably manifested his assent to Uber's terms of use. [Note 40]

c. Contractual defenses. We do not decide, as the dissent suggests, that Uber bears no "responsibility or liability" for the injuries Good suffered. Post at note 7. Rather, we decide only that the parties formed an agreement to arbitrate such disputes. The dissent disagrees, contending that Uber's interface failed to provide reasonable notice because provisions purporting to disclaim Uber's liability, among other terms, would not fall within "a user's reasonable expectations." Id. at 154-155. This contention appears to be rooted in well-founded concerns regarding the fairness of certain terms of Uber's comprehensive standard form contract, [Note 41] specifically, whether the provision that purports to limit Uber's liability for personal injuries resulting from the use of Uber's services to book a ride presented a Hobson's choice [Note 42] that is unconscionable, unenforceable, or voidable. We agree that these are valid concerns that must be addressed in due time. [Note 43] But

Page 145

they are not before us today. Instead, as set forth supra, this case concerns the much more limited question of who will decide these and other important matters: a court of competent jurisdiction or an arbitrator.

Importantly, an agreement to arbitrate is "severable from the remainder of the contract," and "unless the challenge is to the arbitration clause itself, the issue of the contract's validity is considered by the arbitrator in the first instance." Buckeye Check Cashing, Inc. v. Cardegna, 546 U.S. 440, 445-446 (2006). See Boursiquot v. United Healthcare Servs. of Del., Inc., 98 Mass. App. Ct. 624, 630 (2020), quoting Rent-A-Center, 561 U.S. at 71 ("the unconscionability challenge must 'be directed specifically to the agreement to arbitrate [in question] before the court will intervene'"). [Note 44]

Nothing in the conclusion that a contract was formed precludes Good from presenting a defense challenging any of its provisions. [Note 45] See Second Tentative Draft Restatement of the Law of Consumer Contracts § 5 (Apr. 2022) (discussing available

Page 146

defense of unconscionability for terms of contracts that "unreasonably exclude or limit the business's liability or the consumer's remedies . . . for . . . death or personal injury," as analytically separate from issue whether contract was formed because reasonable notice and reasonable manifestation of assent were given); id. at § 2. [Note 46]

We do not suggest that the terms of Uber's standard form contract are valid or enforceable; we leave those grave decisions, as we must, in the hands of the arbitrator, consistent with the express directives of the FAA and MAA. See Rent-A-Center, 561 U.S. at 70-71. Our decision concludes only that the contract formation requirements were met.

4. Conclusion. We reverse the order of the Superior Court judge denying Uber's motion to compel arbitration, and we remand for entry of an order to submit the claims to arbitration. [Note 47]

So ordered.

KAFKER, J. (dissenting). A reckless Uber driver crashes his car, permanently paralyzing his passenger. Do Uber Technologies, Inc., and Rasier, LLC (collectively, Uber), have any responsibility or liability for this terrible injury? A reasonable user of Uber would think, "I am paying a large technology company money for a ride that it has set up to take me from one place to another and I would expect them to have some responsibility for the safety of that ride, right?" Not according to the court. Rather, by checking a box required to continue to use the Uber digital mobile platform application (app) and secure a ride, the passenger has contracted away all his or her rights against Uber without ever being aware of doing so. Because I disagree that the passenger in these circumstances has reasonable notice of any such contract, I dissent.

Page 147

This case is not in any way ordinary, as the court contends. The terms and conditions that Uber seeks to impose through the click of a box differ greatly from what a user would ordinarily expect in such a simple transaction. William Good, like an ordinary Uber user, likely understood that he was continuing his relationship with Uber, where he sought and paid for Uber rides pursuant to the terms of use for the services. Indeed, his explicit goal was to receive a ride from his Somerville apartment to a destination in Boston in exchange for a promise to pay Uber for the ride. What he did not understand was that the terms to which he had purportedly agreed were wide ranging and provided that Uber was not responsible in any way for the ride services procured using the app, even if the services led to the death of or serious injury to the user due to the recklessness or negligence of the driver or Uber, as is alleged to have occurred here. The terms further provided that Uber drivers were not the agents or employees of Uber, and thus not Uber's responsibility, and that all disputes arising out of the ride services were subject to arbitration.

None of this was in any way readily apparent to Good when he was presented with a blocking pop-up screen that prevented him from securing a ride until he checked a box saying he had reviewed Uber's terms. This is because nothing on the blocking pop-up screen alerted the user as to the scope and substance of the terms. The terms themselves were accessed only through a hyperlink that the court recognizes Good likely did not open, as it concludes that he did not have actual notice. The court further recognizes, as we did in Kauders v. Uber Techs., Inc., 486 Mass. 557, 577 (2021), the reality that simply presenting a user with hyperlinked terms will not provide users with notice of the contents of those terms because almost no one will click on the hyperlink or review the terms. Nonetheless, the court concludes that the presence of such a hyperlink provides reasonable notice here. Again, I disagree.

This case, I understand, presents a difficult and unresolved legal issue: how to provide reasonable notice of unexpected contract conditions in the Internet age when most if not all users choose not to open hyperlinks. I conclude, unlike the court, that we must confront this reality. I am also confident that Uber, a sophisticated technology company, is undoubtedly aware of its users' practices, and is easily able to provide other forms of notice with a simple software update. Consequently, because the

Page 148

empirical research discussed infra shows that a hyperlink, without more, is not effective at communicating to a user the scope of a contract's terms and conditions, I would instead require that the notice interface itself, that is, the screen the user actually sees, should at least alert a user as to the scope and significance of the contract that the user is being asked to sign. At a minimum, in these circumstances, the blocking pop-up screen should alert users that they are entering into a legally binding contract, and that pursuant to the contract Uber is not responsible in any way for ride services procured using the Uber app, including for injury or death resulting therefrom. I so conclude recognizing that we have not previously directly addressed how to resolve the problem that most of those contracting over the Internet do not review the terms of those agreements. The common law, including the common law of contracts, must, however, adapt to changing circumstances.

In 1882, Oliver Wendell Holmes remarked that "[t]he doctrine of contract has been . . . thoroughly remodelled to meet the needs of modern times." O.W. Holmes, Jr., The Common Law 247 (1882). Just as the jurists of the late Nineteenth Century remodeled the common law to fit the needs of their times, so too are we called to ensure that our law of contract is suited to the world of the Twenty-first Century, where consumers are surrounded by a plethora of contracts they do not read and may not understand, and simply providing a hyperlink to terms of use will not meaningfully inform consumers of the rights and obligations they take on by using Internet services. When such contracts differ starkly from the reasonable expectations of those entering into the Internet transactions, as they do here, with tragic consequences, more is required than a hyperlink.

In sum, I would hold, considering the totality of the circumstances, that the blocking pop-up screen did not provide reasonable notice to users of such a contractual arrangement. Although the users may have understood that they were entering into some sort of legal relationship with Uber in which they paid Uber in return for ride services, they would not, based on the notice they were provided, reasonably understand that Uber would receive payment but would have no responsibility for the ride services, even if such services led to death or injury due to negligent or reckless conduct by the drivers or Uber. Users would also not reasonably understand that their only recourse was against drivers with whom they had not contracted, and whom the contract defined as a third party for whom Uber had no responsibility.

Page 149

The factors that contribute to this conclusion are, as discussed further infra, the parties to the agreement (that is, Uber and the user, not the user and the driver); the relatively innocuous language of the notice (presented as an update of Uber's terms of use); the nature of the agreement (short-term, small-money transactions for individual rides); the blocking pop-up interface's failure to identify the terms of use as a contract or otherwise as a legally binding agreement containing wide-ranging terms, including those disclaiming Uber's liability for personal injury or death arising out of negligence or recklessness and leaving such liability with a third party; the distinctive aspects of contracting over the Internet, in which users do not read agreements unless they are prompted to understand their significance; and finally, the time pressure imposed on users by blocking access to Uber's ride-hailing app until users assented to the updated terms. Considering all these factors in conjunction with one another, I cannot conclude, as the court does, that the innocuous notice of updated terms provided here, even with a hyperlink to those terms, is sufficient to satisfy the reasonable notice standard established in Kauders, 486 Mass. at 573.

1. Background. a. Kauders decision. Three months prior to Good's receipt of the pop-up notice at issue in the instant case, we examined Uber's contracting process for signing up users, as well as its terms of use, and concluded that Uber failed to give users reasonable notice of the extensive terms of their contract with Uber. Kauders, 486 Mass. at 559. It is undisputed that as a consequence of Kauders, no enforceable contract existed between Good and Uber before the evening of April 25, 2021.

b. The blocking pop-up screen. On April 25, 2021, Good opened the Uber app and was confronted with a blocking pop-up screen that prevented him from accessing or using the Uber app. [Note Dissent-1] The pop-up screen stated, "We've updated our terms," at the top of the screen, and further provided, "We encourage you to read our updated Terms in full." [Note Dissent-2] Between these two sentences was a

Page 150

graphic [Note Dissent-3] of a blue cartoon clipboard with a letter "x" on the bottom left corner of the clipboard, and a blue pencil with the tip pointed near the x. The screen provided blue hyperlinks to Uber's terms of use and to Uber's privacy notice. Users were required to click a checkbox next to text that stated, "By checking the box, I have reviewed and agree to the Terms of Use and acknowledge the Privacy Notice. I am at least 18 years of age." Finally, users were required to click a button [Note Dissent-4] at the bottom of the screen labeled "Confirm."

Although the blocking pop-up screen references updated "Terms" or "Terms of Use" several times, it does not use the words "contract" or "agreement" to describe Uber's terms of use, or otherwise alert the user that significant legal rights are at stake. None of this becomes clear unless the user clicks on the terms of use hyperlink. By contrast, the first paragraph of the terms of use, accessed via the hyperlink, warns users in capital letters, "PLEASE READ THESE TERMS CAREFULLY, AS THEY CONSTITUTE A LEGAL AGREEMENT BETWEEN YOU AND UBER." As I discuss in detail infra, few users click on hyperlinks, especially when they are not on notice as to the hyperlinks' significance. Although it appears that Uber could have tracked whether users, including Good, clicked on the hyperlink, it did not do so.

c. Uber's terms of use. Uber's 2021 terms of use, accessible via the hyperlink, are substantially similar to the terms and conditions discussed in Kauders, 486 Mass. at 561-563. Although the purpose of Uber's app is to provide transportation services for its users, the terms attempt to distance Uber from the services procured using the Uber app, informing consumers, "YOUR ABILITY TO OBTAIN TRANSPORTATION LOGISTICS AND/OR DELIVERY SERVICES FROM THIRD PARTY PROVIDERS THROUGH THE USE OF THE UBER MARKETPLACE PLATFORM AND SERVICES DOES NOT ESTABLISH UBER AS A PROVIDER OF TRANSPORTATION . . .

Page 151

OR AS A TRANSPORTATION OR PROPERTY CARRIER." Uber also represents that its services "ARE PROVIDED 'AS IS' AND 'AS AVAILABLE.' . . . UBER MAKES NO REPRESENTATION, WARRANTY, OR GUARANTEE REGARDING THE RELIABILITY, TIMELINESS, QUALITY, SUITABILITY, OR AVAILABILITY OF THE SERVICES OR ANY SERVICES OR GOODS REQUESTED THROUGH THE USE OF THE SERVICES, OR THAT THE SERVICES WILL BE UNINTERRUPTED OR ERROR-FREE." The terms explicitly disclaim an agency relationship between Uber and its drivers. Rather, the updated terms state that "[THE USER] ACKNOWLEDGE[S] THAT INDEPENDENT THIRD PARTY PROVIDERS, INCLUDING DRIVERS ARE NOT ACTUAL AGENTS, APPARENT AGENTS, OSTENSIBLE AGENTS, OR EMPLOYEES OF UBER IN ANY WAY."

Uber's terms of use also sharply limit its liability to its users:

"UBER SHALL NOT BE LIABLE FOR INDIRECT, INCIDENTAL, SPECIAL, EXEMPLARY, PUNITIVE, OR CONSEQUENTIAL DAMAGES, INCLUDING LOST PROFITS, LOST DATA, PERSONAL INJURY, OR PROPERTY DAMAGE RELATED TO, IN CONNECTION WITH, OR OTHERWISE RESULTING FROM ANY USE OF [UBER'S] SERVICES, REGARDLESS OF THE NEGLIGENCE (EITHER ACTIVE, AFFIRMATIVE, SOLE, OR CONCURRENT) OF UBER, EVEN IF UBER HAS BEEN ADVISED OF THE POSSIBILITY OF SUCH DAMAGES" (emphasis added).

Users agreeing to the Uber terms of use further "agree to indemnify and hold Uber and its affiliates and their officers, directors, employees, and agents harmless from and against any and all actions, claims, demands, losses, liabilities, costs, damages, and expenses (including attorneys' fees), arising out of or in connection with" the use of Uber's services. The terms of use also explain that Uber is free to amend the terms at any time and may choose to inform a user of changes to the agreement by updating the date at the top of the terms, meaning the burden is on the user to frequently check if any changes have been made. Users have no opportunity to object to changes with which they disagree; they must discontinue their use of Uber entirely to signal that they do not agree to changes imposed by Uber.

Page 152

Finally, the terms of use agreement includes an arbitration agreement that requires that almost all disputes [Note Dissent-5] between users and Uber or its drivers be resolved through arbitration. The arbitration agreement precludes users "from bringing or participating in any kind of any class, collective, coordinated, consolidated, representative or other kind of group, multi-plaintiff or joint action against Uber."

2. Discussion. Although this case comes before us as an appeal from the denial of a motion to compel arbitration, the preliminary inquiry is whether a contract has been formed. Kauders, 486 Mass. at 571. "When deciding whether the parties agreed to arbitrate a certain matter . . . , courts generally . . . should apply ordinary state-law principles that govern the formation of contracts." First Options of Chicago, Inc. v. Kaplan, 514 U.S. 938, 944 (1995). See Rent-A-Center, W., Inc. v. Jackson, 561 U.S. 63, 67 (2010) ("The [Federal Arbitration Act] reflects the fundamental principle that arbitration is a matter of contract"); Schnabel v. Trilegiant Corp., 697 F.3d 110, 119 (2d Cir. 2012) ("Whether or not the parties have agreed to arbitrate is a question of state contract law"). The arbitration provision is also just one of many significant provisions in the terms of use. We must therefore consider whether a binding contract exists between Uber and Good. See Kauders, supra at 572. As this transaction occurred on the Internet, we turn to our cases defining the requirements of online contracts, particularly Kauders, supra at 573, in which, as explained above, we interpreted the requirements for online ride service contracts. Indeed, there we considered essentially the same contract at issue in the present case. Id. at 561-562.

For an online contract to be enforceable, "there must be both reasonable notice of the terms and a reasonable manifestation of assent to those terms." Kauders, 486 Mass. at 572, citing Ajemian v. Yahoo!, Inc., 83 Mass. App. Ct. 565, 574-575 (2013), S.C., 478 Mass. 169 (2017), cert. denied sub nom. Oath Holdings, Inc. v. Ajemian, 584 U.S. 910 (2018). "[T]he burden of proof on both prongs is on Uber, the party seeking to enforce the contract." Kauders, supra, citing Canney v. New England Tel. & Tel. Co., 353 Mass. 158, 164 (1967).

Whether a consumer has been provided reasonable notice of the terms and conditions of an online contract is "a fact-intensive

Page 153

inquiry," Kauders, 486 Mass. 573, quoting Meyer v. Uber Techs., Inc., 868 F.3d 66, 76 (2d Cir. 2017), requiring consideration of the totality of the circumstances. Among the factors courts should consider in determining reasonable notice are "the nature, including the size, of the transaction, whether the notice conveys the full scope of the terms and conditions, and the interface by which the terms are being communicated." Kauders, supra, citing Sgouros v. TransUnion Corp., 817 F.3d 1029, 1034 (7th Cir. 2016). We have also explained that "[f]or Internet transactions, the specifics and subtleties of the 'design and content of the relevant interface' are especially relevant in evaluating whether reasonable notice has been provided." Kauders, supra, quoting Meyer, supra at 75.

a. Nature of the transaction and full scope of terms. In Kauders, 486 Mass. at 575, we observed: "Reasonable users may not understand that, by simply signing up for future ride services over the Internet, they have entered into a contractual relationship." See, e.g., Sgouros, 817 F.3d at 1035 (signing up for credit-score information over Internet not obviously contractual). Even if users understand they may be entering into some sort of contractual relationship, "[i]t is . . . by no means obvious that signing up via an app for ride services would be accompanied by the type of extensive terms and conditions present here." Kauders, supra.

Additionally, as we explained in Kauders, 486 Mass. at 577, "Uber is undoubtedly aware . . . [that] most of those registering via mobile applications do not read the terms of use or terms of service included with the applications." See, e.g., Ayres & Schwartz, The No-Reading Problem in Consumer Contract Law, 66 Stan. L. Rev. 545, 547-548 (2014) (describing empirical evidence showing less than one percent of consumers access online contracts); Bakos, Marotta-Wurgler, & Trossen, Does Anyone Read the Fine Print? Consumer Attention to Standard-Form Contracts, 43 J. Legal Stud. 1, 3 (2014) ("Our main finding is that regardless of how strictly we define a shopper, only one or two in 1,000 shoppers access a product's [End User License Agreement] for at least [one] second . . ."). See also Conroy & Shope, Look Before You Click: The Enforceability of Website and Smartphone App Terms and Conditions, 63 Boston Bar J. 23, 23 (Spring 2019) ("Most users will not have read the terms and, in some instances, may not have even seen the terms or any reference to them"); Marotta-Wurgler, Will Increased Disclosure Help? Evaluating the

Page 154

Recommendations of the ALI's "Principles of the Law of Software Contracts," 78 U. Chi. L. Rev. 165, 179-181 (2011) (clickwrap contracts increased proportion of consumers who access contract terms by only 0.36 percent compared to "browsewrap" agreements, where users are only provided notice of contract terms by link somewhere on website and are not required to click box to indicate assent). [Note Dissent-6] This may not be a major concern when the terms of an online agreement are straightforward and obvious -- for example, a payment for an article of clothing at a set amount -- this is far more problematic when the significance and complexity of the legal arrangements are not readily apparent from the transaction itself. My dissent addresses the latter problem.

Further complicating the nature of the transaction and the notice requirements here is the counterintuitive triangular nature of the relationship where the user contracts only with Uber, but the only person responsible and liable for the services under the terms of use is Uber's driver. The terms require users to acknowledge that Uber's drivers are third-party providers and not Uber's agents or employees, regardless of whether this is a correct statement of the law, and regardless of a user's understanding of the legal consequences of such an acknowledgement. [Note Dissent-7]

The legal relationships created by the terms differ strikingly from a user's reasonable expectations. Using the Uber app, users

Page 155

enter into small-dollar ride service transactions with Uber and provide payment to Uber in exchange for these Uber rides. They have been asked to read and agree to Uber's terms of use. Users do not contract in any way with individual drivers, and the blocking pop-up screen interface makes no mention of drivers. Nonetheless, the terms of use that Uber would have users sign shift responsibility for the services solely to the drivers. The terms go so far as to state that Uber is not a transportation company and does not provide transportation services, something that would obviously surprise the ordinary user, [Note Dissent-8] who has ordered an "Uber." There is nothing on the face of the notice indicating that Uber is not the party providing the transportation services and is not responsible in any way for those services. Users would reasonably expect Uber to be responsible for those services and the drivers providing them. The terms provide for the opposite of these expectations.

The terms of use thus establish a counterintuitive three-party relationship in which Uber receives payment for requested transportation services but has no liability for serious injury or death arising out of such transportation services. Rather, a user's only recourse is against a third party, the driver, with whom the user never contracted. [Note Dissent-9] With these concerns in mind, I turn to the

Page 156

notice and the interface at issue, and whether it provided reasonable notice of this counterintuitive contractual arrangement to a user.

b. Interface and notice. I begin by recognizing that the notice interface here differed from the notice we considered in Kauders, 486 Mass. at 577-578, in a variety of respects. In Kauders, the notice was provided as part of the original sign-up and payment process. The notice was not presented in a blocking pop-up screen as a user requested and expected a ride. The terms in Kauders were therefore newly presented to a user and not framed as an update. Id. at 578. And whereas in Kauders users were "simply never directed to the notice and the link" to Uber's terms of use without going through a multistep process, the blocking pop-up screen at issue here did direct a user's attention to the terms of use hyperlink. See id. at 579. All these distinctions are relevant to the reasonable notice inquiry, including whether the user would have reason and enough time to open and review the terms of use.

More specifically, the blocking pop-up screen presented to Good in April of 2021 as he requested a ride informed him that Uber had "updated [its] terms." It "encourage[d]" him "to read [the] updated Terms in full" and provided a hyperlink to the terms of use and Uber's privacy notice. If the hyperlink was clicked, the user would very quickly be put on notice that significant legal rights were at stake, as the first paragraph identified the terms as "A LEGAL AGREEMENT BETWEEN [THE USER] AND UBER" and directed users to "PLEASE READ THESE TERMS CAREFULLY." None of this urgency, however, was present or readily ascertainable on the basis of the blocking pop-up screen presented to users. My focus is on the deficiencies in the notice provided in the blocking pop-up screen, which I consider significant for the reasons discussed infra, all of which suggest that a user would not click on the hyperlink or review the terms in these circumstances.

The blocking pop-up screen, which all users would see when accessing the Uber app, did not use the term "contract" or "agreement," which would better alert users as to the significance of the transaction that they were to enter into with Uber. It makes no mention of limitation of liability, or otherwise indicates that Uber has no responsibility for the drivers it is providing the user for the ride services. Cf. Brennan v. Ocean View Amusement Co., 289 Mass. 587, 593-594 (1935) (where defendant sought to bind

Page 157

plaintiff through contract "printed on the ticket which the plaintiff bought," plaintiff would only "be bound thereby, if [the conditions and limitations in the contract] were brought to his attention in such a manner that a person of ordinary intelligence in his position would have known of and understood"); Fonseca v. Cunard S.S. Co., 153 Mass. 553, 556 (1891) ("The precise question . . . is whether the 'contract ticket' was of such a kind that the passenger taking it should have understood that it was a contract containing stipulations which would determine the rights of the parties . . ."); Sgouros, 817 F.3d at 1034 (noting that contracts printed on cruise ship tickets "present problems similar to those of agreements formed on the Internet"). [Note Dissent-10]

Furthermore, even the notice's reference to updated terms is somewhat inaccurate and misleading. At the time Good received the blocking pop-up screen, there were no legally binding terms and conditions in existence between Uber and Good. See Kauders, 486 Mass. at 579. The use of the term "updated" suggested some substantial similarity in the relationship between Uber and its users before the "update" and after, which downplayed the significance of the user's assent to the "updated" terms. In reality, no enforceable contract whatsoever existed between Massachusetts users and Uber prior to the update, whereas after the update, users purportedly agreed to an extensive set of contractual terms that severely abridged their rights against Uber. See id. at 559. Although the pop-up screen "encourage[d]" users to review the terms, framing the terms as only an "update" obscured the importance and far-reaching consequences of the terms of use and thereby discouraged users from reviewing the terms. [Note Dissent-11] Moreover, the updates were delivered using an interface apparently used by Uber on other occasions to present users with advertisements and promotional offers, further diminishing the terms' significance to

Page 158

a user.

Importantly, users were presented with the "updated" terms at a time when they were seeking immediate use of Uber's services and were prevented from accessing the Uber app until they signaled their assent. The timing of the pop-up screen, coupled with the "update" framing discussed supra, thus prompted users just to accept the terms and conditions rather than review them because the terms were presented as a relatively innocuous update to a long-running relationship in a circumstance where many users would not have the time to fully review a lengthy contract. [Note Dissent-12] See Kauders, 486 Mass. at 577. See also Archer v. Grubhub, Inc., 490 Mass. 352, 361 (2022) (reasonable notice requires that party had adequate opportunity to view terms of agreement). Contrast Singh v. Uber Techs., Inc., 235 F. Supp. 3d 656, 661 (D.N.J. 2017), vacated on other grounds by 939 F.3d 210 (3d Cir. 2019) (driver accepted agreement with Uber three months after it was presented to him for review).

I therefore cannot conclude that users, having already decided to use the Uber app to order a ride and potentially facing time pressure to get to a destination, would, when confronted with a blocking pop-up screen that simply informed them of "update[s]" to Uber's terms of use, choose to postpone their trip or change their mode of travel in order to review the updates to the terms of use before next using the Uber app. [Note Dissent-13] Rather, confronted with an innocuous notice such as was presented here, a user would simply click through the pop-up screen to access Uber's services. The potential time pressure imposed on users through the blocking pop-up interface is thus another factor contributing to our conclusion that users were not provided reasonable notice of Uber's

Page 159

terms of use. [Note Dissent-14]

In analyzing the interface, I again emphasize the reality that most users will not click a hyperlink to access the terms, especially when there is nothing alerting the user to their importance. See Kauders, 486 Mass. at 577, quoting Ayres & Schwartz, supra at 547-548. See also Bakos, Marotta-Wurgler, & Trossen, 43 J. Legal Stud. at 3; Conroy & Shope, 63 Boston Bar J. at 23; Marotta-Wurgler, 78 U. Chi. L. Rev. at 179-181. Where, as here, the terms diverge significantly from the reasonable expectations associated with the transaction at issue, and involve a waiver of important legal rights, I would hold that reasonable notice requires that an interface in some way communicate the scope and significance of the contract terms. See Kauders, supra at 573 (reasonable notice depends in part on "whether the notice conveys the full scope of the terms and conditions"). [Note Dissent-15]

I do recognize, however, that the terms and conditions were more readily accessible than they were in the interface discussed in Kauders, 486 Mass. at 578-579. Had the notice reasonably alerted the user to the significance and scope of the terms, users would have been more likely to access the terms, or at least would have been adequately warned about the need to do so. [Note Dissent-16] In these

Page 160

circumstances, notice that users were being asked to sign a legally binding contract, and that pursuant to the contract Uber was not responsible for the ride services procured through the app, would have been sufficient.

c. Clickwrap agreements: the difference between notice and assent. Next, I address the effects of requiring the user to check a box stating, "I have reviewed and agree to the Terms of Use and acknowledge the Privacy Notice. I am at least 18 years of age," and click a button at the bottom of the screen labeled "Confirm." Uber argues that because the blocking pop-up screen presented to Good in 2021 is an example of a clickwrap agreement, it is per se enforceable. This misunderstands and impermissibly simplifies the analysis a court must undertake to determine the enforceability of an online contract. See Kauders, 486 Mass. at 573-574. A court must consider both whether the user had reasonable notice of contract terms and conditions and whether there was a reasonable manifestation of assent by the user. Id. at 572. The significance of a clickwrap interface differs depending on whether the court is considering the reasonableness of the notice or the reasonableness of the manifestation of assent.

In Kauders, we observed that a clickwrap agreement, by "[r]equiring an expressly affirmative act, . . . can help alert users to the significance of their actions. Where they so act, they have reasonably manifested their assent." Id. at 575. A clickwrap agreement therefore serves two different purposes. It can first help alert the reader as to the significance of the transaction, and thereby contribute to the reasonableness of the notice. Second, requiring users to click that they agree can demonstrate the reasonableness of their assent. The clickwrap interface may thus be determinative of a reasonable manifestation of assent but is only one factor among many in determining whether a user-facing interface, as a

Page 161

whole, provides reasonable notice of a contract's terms and conditions. See id. This is in part because empirical research suggests that clickwrap interfaces only marginally increase the frequency with which users actually interact with the terms of online contracts. Marotta-Wurgler, 78 U. Chi. L. Rev. at 179-181. Unless users are on reasonable notice of the terms and their scope and significance, users may be assenting to something very different from what they expected or understood.

In the instant case, the small-dollar nature of the transaction, the innocuous framing of the terms of use as an "update" to Uber's terms of use, the reasonable expectations of a user as to what this update would contain, and the pressure to assent in order to access Uber's rideshare service all discounted the importance of reading the terms and discouraged the user from reviewing the terms, even where the terms were accessible and the user was required to check a box saying he or she had reviewed them. In sum, in the totality of these circumstances, there has not been reasonable notice of the significance and scope of the contract.

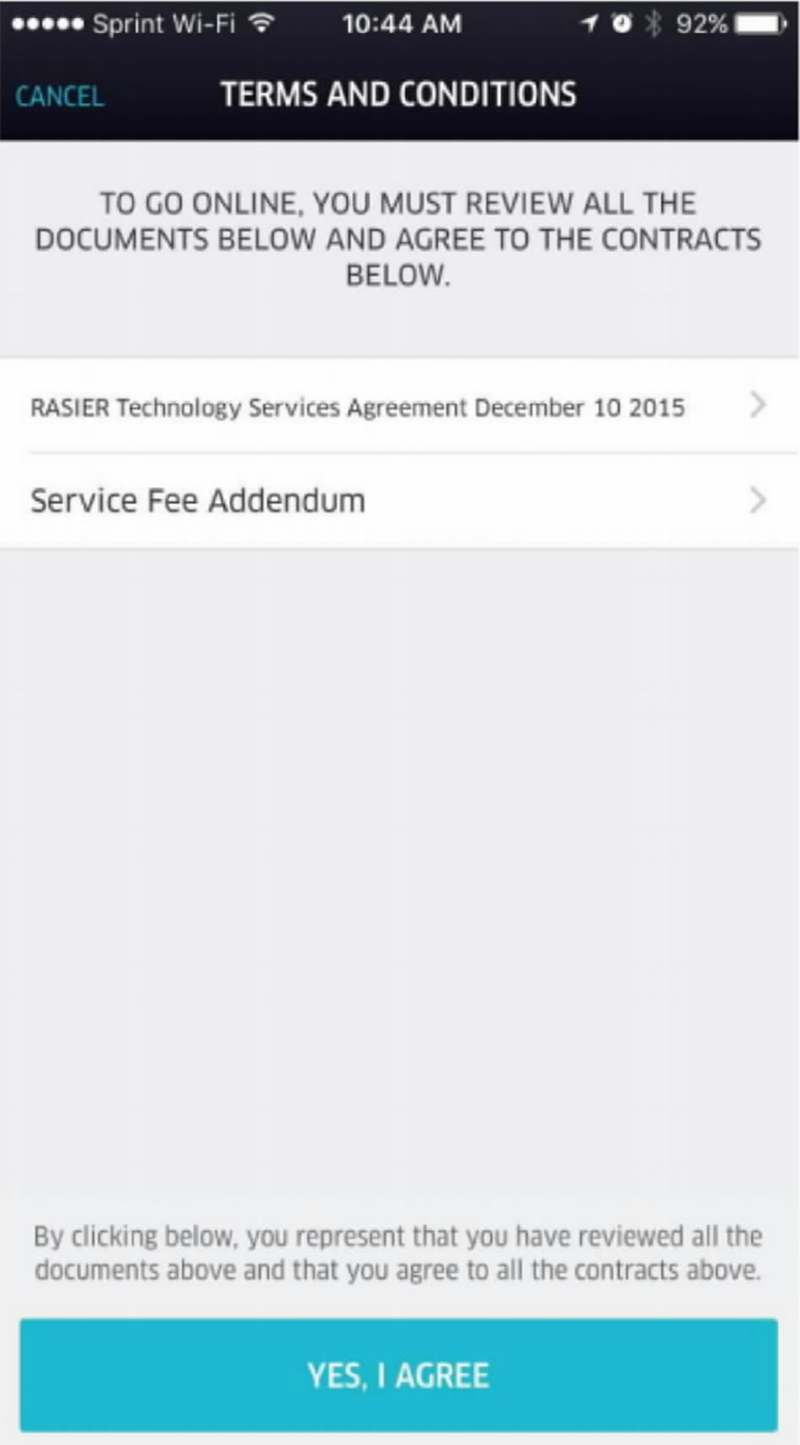

d. The different notice provided to drivers. Finally, as we explained in Kauders, the deficiencies in the notice provided by Uber to its users are brought into sharper focus when one considers the interfaces it has used to inform its drivers about the contracts that govern their relationship with Uber. Around 2016, users seeking to register as drivers on Uber's platform were presented with a blocking pop-up screen that informed them in capital letters, "TO GO ONLINE, YOU MUST REVIEW ALL THE DOCUMENTS BELOW AND AGREE TO THE CONTRACTS BELOW." Capriole vs. Uber Techs., Inc., U.S. Dist. Ct., No. 1:19-cv-11941-IT (D. Mass. Mar. 31, 2020). [Note Dissent-17] The screen provided links to two agreements, the "RASIER Technology Services Agreement" and a "Service Fee Addendum." Id. Finally, a button at the bottom of a driver's screen stated, "YES, I AGREE." Id. After a driver clicked the button, "a new box popped up in the middle of the screen, which read 'PLEASE CONFIRM THAT YOU HAVE REVIEWED ALL THE DOCUMENTS AND AGREE TO ALL THE NEW CONTRACTS.'" Id. See Kauders, 486 Mass. at 559 ("a review of the case law reveals that Uber has no trouble providing such reasonable

Page 162

notice . . . [to] its own drivers"); Singh, 235 F. Supp. 3d at 661 (driver was required twice to confirm he had reviewed and accepted agreement with Uber by clicking "YES, I AGREE" on two different screens, and driver had as much time as he found necessary to review agreement, accepting agreement three months after it was made available to him).