The plaintiffs, John Nicosia and Robin Nicosia, husband and wife, of North Reading in the County of Middlesex, the owners of the premises at 7 North Street (the "plaintiffs") seek a declaration as to their right to use the so-called "Old Road" situated on land of the defendants, Thomas W. Jurczak and Constance M. Jurczak, husband and wife, of said North Reading, the owners of the premises at 5 North Street (the "defendants"). The defendants deny that the plaintiffs have such a right and claim it has been lost by abandonment or extinguishment by the exercise of adverse possession. The other original defendants, James T. Gallagher, Helen E. Gallagher, Anita L. Merrill and Leslie W. Merrill, Jr., owners of lands which also abut on said road, were defaulted pursuant to Mass. R Civ. P. 55(a) in open court on July 14, 1986 and so notified. None of these defaulted parties has appeared although the defendant James T. Gallagher testified at the trial. The Court attempted during a pre-trial hearing on injunctive relief to assist the parties in negotiating a settlement of the dispute between them, but the parties never succeeded in reaching a settlement.

A trial was held at the Land Court on June 19, 1987 and a stenographer was appointed to record and transcribe the testimony. The Jurezaks were represented initially by counsel who was permitted to withdraw. The defendant, Thomas W. Jurczak, in spite of the Court's advice to the contrary, proceeded pro se. Eleven exhibits were introduced into evidence, two chalks were provided and four witnesses testified: John A. Nicosia, Thomas W. Jurczak, James T. Gallagher and Anita Reinhold, an attorney who examined the titles of both parties. All exhibits introduced into evidence are incorporated herein for the purpose of any appeal.

On all the evidence I find and rule as follows:

1. The plaintiffs, John A. Nicosia and Robin Nicosia reside at and are the owners of record of the premises known as 7 North Street in North Reading, Middlesex County. Said premises were conveyed to them by Charles H. Mannion and Jean F. Mannion, by deed dated April 30, 1984 and recorded with the Middlesex South District Registry of Deeds (to which Registry all recording references herein refer) in Book 15549, Page 223 (Exhibit No. 2).

2. The defendants Thomas W. Jurczak and Constance M. Jurczak are the residents and record owners of the premises known as 5 North Street in North Reading, which were conveyed to them by Joseph S. Carder, Administrator of the Estate of Lillian F. Carder by deed dated January 13, 1966 and recorded in Book 11029, Page 233.

3. Both the plaintiffs and the defendants claim under common grantors, Walter L. Stowe, et ux. The plaintiffs' land was the first of the two parcels, i.e., one to the predecessors in title of the plaintiffs and the other to the predecessors in title of the defendants [Note 1] to be conveyed out by Mr. and Mrs. Stowe by deed to Thomas L. Foley on June 13, 1934, recorded in Book 5835, Page 360 (Exhibit No. 6). This deed contained the following grant of an appurtenant easement on which the plaintiffs now rely: "together with the right to use a private way as now laid out for the right of access to the garage, for both foot and vehicle passage as now on the premises." An identical provision was set forth in each of the subsequent conveyances of this property.

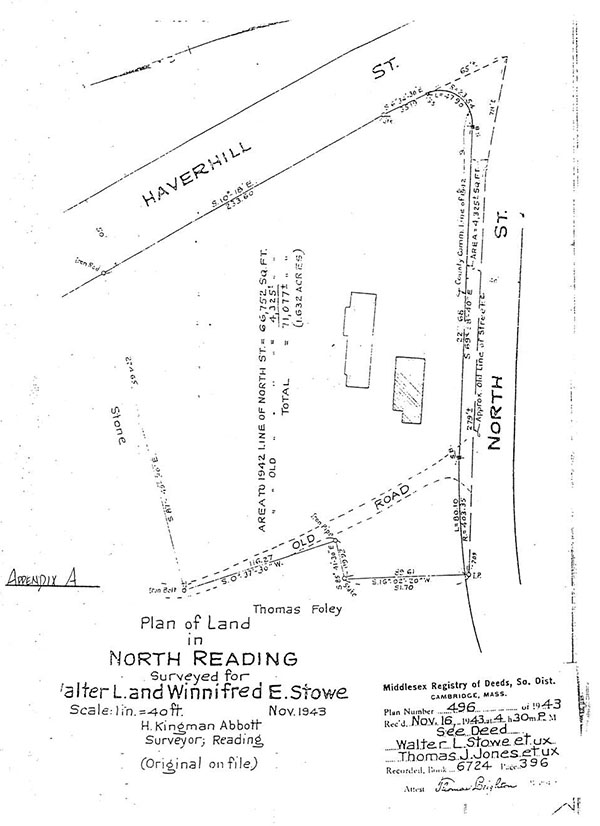

4. On November 13, 1943, the defendants' lot was conveyed out by Walter L. Stowe and Winnifred E. Stowe, the common grantors, to Thomas J. Jones and Thelma Jones by deed recorded in Book 6724, Page 396 (Exhibit No. 7). This deed failed to mention the right of way previously granted to Thomas L. Foley but does refer to the plan entitled "Plan of Land in North Reading - Surveyed for Walter L. and Winnifred Stowe" dated November 1943 by H. Kingman Abbott and recorded as Plan 496 of 1943 (Exhibit No. 8; a portion of which is attached hereto as Appendix A). Shown on this plan is a way labeled "Old Road" leading from North Street over the lot conveyed to Jones to and beyond an iron bolt at the northwest corner of the land conveyed to Jones with that previously conveyed to Thomas Foley. The portion of the way shown on this plan is the focal point of the dispute between these parties.

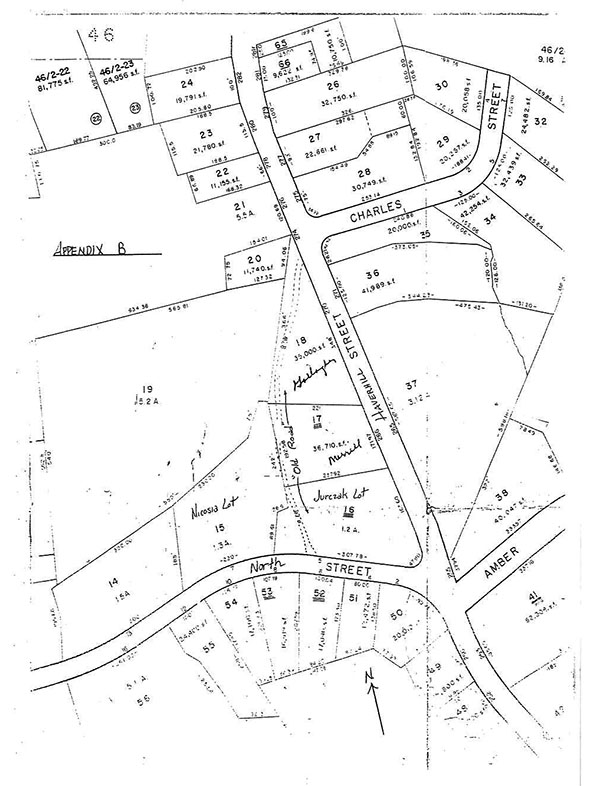

5. The way shown as the "Old Road" on the 1943 plan of Abbott (Exhibit No. 8) is also known as "Old County Road" and is shown on the North Reading Assessors' Sheet No. 45 (Exhibit No. 1, a portion of which is attached hereto as Appendix B) as a right of way running in a north-northwesterly direction from North Street to Haverhill Street. The surface of this way is presently unpaved although the road bed is gravel and there is a culvert which drains a seasonal wetland. There are also curb cuts on both Haverhill Street and North Street where each intersects with the "Old Road."

6. The garage referred to in the 1934 grant of easement by Walter L. Stowe and Winnifred E. Stowe to Thomas L. Foley, burned to the ground in 1981. It has not since been rebuilt although some of the original cement footings or foundation remain (Exhibit No. 3E), and the plaintiffs intend to construct a new garage on the old site. One of the areas in dispute between the parties is the plan of plaintiffs to bring a cement truck over the right of way from North Street to their land; defendants claim that the weight of the cement truck will cause harm to their septic system which is located beneath the right of way. Defendants also appear to assume that since the plaintiffs have the right to use the "Old Road" from North Street to Haverhill Street, they should be required to traverse the "Old Road" from Haverhill Street rather than from North Street.

7. The defendants periodically have blocked the portion of the way in question which crosses their land, particularly a section closest to North Street as noted above. It is in this section of the way that the septic system is located. After the garage burned in 1981 the defendants planted a tree adjacent to the entrance to the right of way at North Street even though the predecessor in title of the plaintiffs warned Mr. Jurczak that the tree eventually would grow in such a way as to interfere with the way. From time to time the defendants have piled brush and other debris on the "Old Road" or have parked on it in an effort to block its use.

8. Both Mr. Stowe and his grantee Mr. Foley worked for the Department of Public Works and were good friends. Presumably that is why the Stowes sold the land to Mr. Foley so that he would be available when needed to work on snow clearance or other department projects. There was originally a three car garage on the plaintiffs' property in which a Department truck, Foley's personal car and a woodworking shop were kept. Much of the Foley land was granite. The terrain was such that access to an appurtenant building was difficult. This appears to be the explanation for the grant of the right of way across land retained by the Stowes. At the time of the fire in 1981 the plaintiffs' property was owned by Charles H. Mannion, et ux, and a horse was being kept in the garage. The horse died during the fire. The emergency vehicles including the fire trucks, used the right of way to reach the garage and thereafter to remove the horse's carcass therefrom.

The plaintiffs claim that the grant made to their predecessor in title, Thomas L. Foley, by Mr. and Mrs. Stowe has not been lost and that it is still in full force and effect. The defendants conversely argue that the right of way has been abandoned or that their own use has been sufficiently adverse to extinguish the right of way. Implicit in their position also is the fact that the grant was tied in to the existing garage and that when the garage was destroyed by fire, the right of way terminated. The established rule of easements that mere non-user is insufficient to prove abandonment is applicable here. Delconte v. Salloum, 336 Mass. 184 , 188 (1957); Parlante v. Brooks, 363 Mass. 879 , 880 (1973) (rescript); Emery v. Crowley, 371 Mass. 489 , 495 (1976). In order to establish abandonment there must be a showing of non-use coupled with an intent to abandon. Desotell v. Szczygiel, 338 Mass. 153 , 158-159 (1958). While admittedly the evidence in this case, as a whole, is sparse and much is immaterial, there has been no showing that the plaintiffs or their predecessors intended to give up their right to use the way. Since 1984 when the plaintiffs took title to the dominant estate, there may have been a brief period of non use, and while their predecessors, the Mannions, used the garage as a horse barn during the period just prior to its destruction by fire in 1981, a lack of vehicular use does not, however, prove an intent not to use the right of way for such purposes in future. In any event, the exercise of rights of way may vary from time to time and so long as such use is reasonably necessary to full enjoyment of the dominant estate and does not overburden the servient estate by exceeding the scope of the rights held, it will not constitute grounds for termination of such use nor prove an intent to abandon. Brodeur v. Lamb, 22 Mass. App. Ct. 502 , 504 (1986); Tehan v. Security National Bank, 340 Mass. 176 , 182 (1959).

It might be argued, in view of the language of the grant, that the destruction of the garage terminated the purpose of the easement, but the garage is to be rebuilt, and there was some evidence that the plaintiffs' frontage on North Street is such that access from that direction would be difficult. Moreover, the express grant of easement cannot be extinguished by a temporary loss of the structure it is intended to serve. Emery v. Crowley, 371 Mass. at 495 (1976); Compare Brooks, Gill & Co. v. Landmark Properties, 217 Ltd. Partnership, 23 Mass. App. Ct. 528 , 532 (1987) (destruction of structure containing easement).

The argument for extinguishment of the express grant of easement by prescriptive use is equally unconvincing on the facts presented. While it is true that some vegetation may have overgrown that portion of the way over the defendants' property closest to North Street, and Mr. Jurczak did plant a tree in this area, such an act and such conditions will neither prove abandonment nor constitute a sufficiently adverse use for extinguishment. First National Bank of Boston v. Kanner, 373 Mass. 463 , 467 (1977) citing Desotell, supra at 159. As explained by Justice Quirico in First National Bank of Boston v. Kanner, neglect by the dominant tenant may be sufficient for abandonment where shown to be coupled with sufficient adverse use by the servient tenant. Id. citing Sindler v. William M. Bailey Co., 348 Mass. 589 , 593 (1965); See also Lemieux v. Rex Leather Finishing Corp., 7 Mass. App. Ct. 417 , 421-422 (1979). The evidence did not establish that these conditions were present here.

The defendants introduced photographic evidence showing a car parked so as to block the way near North Street and a pile of loam alleged to have been placed in this area by Mr. Jurczak (Exhibit Nos. 3C, 3D, 10 and 11). Neither of these obstructions was shown to have been in existence for the necessary twenty year period and, in any event, this action was filed to put an end to them not long after they had apparently begun. The burden as to the elements of extinguishment by prescription rests with the owner of the servient estate. Lemieux v. Rex Leather Finishing Corp., 7 Mass. App. Ct. at 422. There was no sufficient showing here that the defendants' acts of obstruction were so complete nor of such duration as to constitute grounds for finding extinguishment. See Shapiro v. Burton, 23 Mass. App. Ct. 327 , 330-331 (1987); Brennan v. DeCosta, 24 Mass. App. Ct. 968 , 969 (1987) (rescript).

There is nothing in the language of the grant which compels the conclusion that its duration was limited to the original garage on the property since the physical characteristics are such that access to the land of the plaintiffs from North Street appears possible only by use of the land of the defendants. By constructing their septic system within the right of way, defendants assumed the risk that use by the plaintiffs might interfere with the system. See Texon, Inc. v. Holyoke Machine Co., 8 Mass. App. Ct. 363 , 366 (1979). While it is true that the owner of the fee may continue to make any use of it which is not inconsistent with the easement, he cannot be heard to complain if in the proper use of the easement some harm is done to the system. In any event, the possible damage which may occur would appear to be limited to the period of construction of the garage, and it is the suggestion of the Court that this can be forestalled by the defendants' buttressing the surface in such a way as to protect the underground system. Alternatively, it is the responsibility of the defendants to relocate the septic system which they should not have constructed within the location of the "Old Road", the easement appurtenant to the plaintiffs' land being a matter of record, of which the defendants at the least had constructive notice. See Highland Club of West Roxbury v. John Hancock Mutual Life Ins. Co., 327 Mass. 711 ,714 (1951); Shapiro v. Burton, 23 Mass. App. Ct. at 335.

An opportunity was afforded the defendants in the initial stages of this litigation to relocate the right of way to avoid any possible interference with their septic system, but the relocation was never accomplished. The Court is prepared to grant to the plaintiffs and to

others entitled, an alternate route across the land of the defendants to the land of the plaintiffs and the remainder of the "Old Road" if the plaintiffs are of the opinion that physically it would serve their purpose and permit them to reach their land as easily as by using the "Old Road". They cannot be compelled, however, to accept a different route.

The plaintiffs also have asked the Court to delineate the extent of their rights in the "Old Road". The grant to the plaintiffs was of a right of access to the garage for both foot and vehicle passage. The General Court has now expanded the rights included within this language (see G.L. c. 187, §5) to encompass an easement for all purposes rather than simply for access. As to any specific use beyond passage, the Court declines to rule on the extent of the plaintiffs' rights without a question being posed. As the owners of the dominant tenement, the plaintiffs have the right to make the right of way passable, to clear trees and shrubs therefrom and to generally provide suitable access from the street to their property. See Guillet v. Livernois, 297 Mass. 337 (1937). Under the circumstances here, there is nothing in the background of the grant to the plaintiffs, however, that suggests they were given the right to blacktop the surface of the way, or otherwise to construct it in such a way as would adversely reflect on the attractiveness of the defendants' land.

The defendants are not to interfere with the plaintiffs' use of the way or with any work that the plaintiffs may undertake to make the way passable. Moreover, it is the obligation of the defendants to remove from the limits of the "Old Road" as shown on Exhibit No. 8 any obstacles placed therein or any tree which the defendants may have planted on or adjacent to the lines of said way.

The plaintiffs have requested several rulings of law, of these I grant Nos. 1, 3, 5, 6, 8 and 9 and deny requests 2 and 4. As to request No. 7, it is a correct statement of law, but it is inapplicable here.

Judgment accordingly.

JOHN NICOSIA and ROBIN NICOSIA vs. THOMAS W. JURCZAK, CONSTANCE M. JURCZAK, JAMES T. GALLAGHER, HELEN E. GALLAGHER, ANITA L. MERRILL and LESLIE W. MERRILL, JR.

JOHN NICOSIA and ROBIN NICOSIA vs. THOMAS W. JURCZAK, CONSTANCE M. JURCZAK, JAMES T. GALLAGHER, HELEN E. GALLAGHER, ANITA L. MERRILL and LESLIE W. MERRILL, JR.