In this case, Peter J. Murphy and Elizabeth Murphy (collectively, Plaintiffs), Trustees of the Three Eagles Nest Road Nominee Trust (Trust) and Edward and Eileen OBrien, Edward Corbo, Virginia Doherty, and Paul Kelly (collectively, South Side Plaintiffs), filed a complaint against defendants Kenneth J. Conway and Carol A. Conway, individually and as Trustees of the Windmill Trust (collectively, Defendants), seeking declaration of the plaintiffs rights to use an easement, an injunction ordering removal of structures blocking the claimed easement, and an award of damages and attorneys fees.

PROCEDURAL HISTORY

On January 1, 2006, Plaintiffs and South Side Plaintiffs commenced this action by filing a complaint against the Defendants. Plaintiffs own the property at 3 Eagles Nest Road in Scituate, Massachusetts. The South Side Plaintiffs own lots on the south side of Eagles Nest Road. Defendants own the property at 15 Eagles Nest Road. The dispute before the court concerns the easement set forth in a deed dated December 23, 1911, which all of the plaintiffs (Plaintiffs and the South Side Plaintiffs collectively, plaintiffs) claim gives them the right to travel over the eastern half of Eagles Nest Road, where it passes over Defendants15 Eagles Nest Road property. Plaintiffs seek a declaration of their easement rights in that land, an injunction ordering the removal of structures blocking the claimed easement, and an award of damages and attorneys fees.

On April 21, 2006, Defendants filed an answer denying the plaintiffs claims, alleging that any rights the plaintiffs once had in the easement area had been extinguished. Defendants also filed a counterclaim, seeking an order directing plaintiffs to remove obstacles from Eagles Nest Road. On April 2, 2007, Plaintiffs filed a Suggestion of Death on behalf of deceased Plaintiff Peter J. Murphy. He passed away on November 26, 2006. He had been the co-trustee of the Three Eagles Nest Road Nominee Trust. The litigation has proceeded with Elizabeth A. Murphy as the representative of the Trust and record owner of the 3 Eagles Nest Road property.

On June 11, 2007, Defendants filed a Motion for Partial Summary Judgment, seeking to dismiss the claims of the South Side Plaintiffs. Defendants contended that, as a result of the state of title to the disputed portion of Eagles Nest Road, the record easement set out in the 1911 deed did not benefit the lots on the southern side of Eagles Nest Road.

On July 12, 2007, Plaintiffs filed a Motion to Amend Complaint, an Opposition to the Defendants Motion for Summary Judgment, and a Motion for Summary Judgment of their own. Plaintiffs sought to amend their complaint to include various theories of implied easement and easements based on use, in addition to the express easement theories raised in the original complaint. Plaintiffs sought summary judgment declaring their rights to use the easement and ordering the removal of alleged obstacles to that use.

On August 13, 2007, Defendants filed their oppositions to the Motion to Amend and to the Motion for Summary Judgment. Defendants opposed the Motion to Amend on grounds of undue delay on the part of the Plaintiffs and resultant prejudice to the Defendants. Defendants opposed the Motion for Summary Judgment on the grounds that Plaintiffs filing was improper and that issues of material fact precluded summary judgment.

On August 23, 2007, the parties appeared and argued Plaintiffs Motion to Amend and Defendants Motion for Partial Summary Judgment. Following oral argument, Defendants Motion for Partial Summary Judgment was granted. For reasons laid upon the record from the bench, and memorialized in a docket entry made at the conclusion of the hearing, the court held that as a result of a 1911 conveyance (in the deed which contains the language of the easement disputed in the pending litigation) title to a specified portion (including the full width of the eastern half) of the fee of Eagles Nest Road passed to the deeds grantee, by operation of the provisions of G.L. c. 183, section 58. Accordingly, the court ruled, subsequent purported grants of easement in favor of the owners of the lots on the south side of Eagles Nest Road which now are owned by the South Side Plaintiffs were ineffective, leading the court to rule that they hold no record easement rights to use the eastern half of Eagles Nest Road. Plaintiffs Motion to Amend was taken under advisement.

On September 20, 2007, this court issued an Order conditionally granting, in part, Plaintiffs Motion to Amend Complaint. The Order permitted plaintiffs to amend their complaint to include a theory of easement by prescription on behalf of the South Side Plaintiffs, but only, given that the amendment request came after the preparation and filing of Defendants partial summary judgment motion, upon payment of a certain portion of Defendants legal fees. These parties were given the election of paying those fees or not, with the proviso that should they decline to do so, the amendment request would be denied. The Order denied the South Side Plaintiffs request to add alternative theories of easement by implication and by estoppel. The Order denied Plaintiff Elizabeth Murphys request to add alternative theories of easement by estoppel and by implication.

On October 18, 2007, Plaintiffs responded to the Order with a letter declaring an intent not to comply with the conditions of the Order. Plaintiffs withdrew their Motion to Amend. On October 31, 2007, this court issued an Order denying plaintiffs Motion to Amend for failure to comply with the conditions the September 20, 2007 Order had set forth.

On May 2, 2008, a Joint Pretrial Conference Memo was submitted. On May 8, 2008, a Joint Motion for Entry of Separate and Final Judgment was filed on behalf of the South Side Plaintiffs. On October 1, 2008, a Joint Pretrial Memorandum was filed, laying out the agreed and contested facts along with the witnesses and exhibits which would be relied upon at trial.

On October 7, 2008, a motion for entry of separate and final judgment was filed. The court denied the requests that judgment enter separately, finding the requirements of Mass. R. Civ. P. 54(b) to have been unmet. From this point forward, Elizabeth Murphy (Plaintiff), individually and as trustee of the Three Eagles Nest Road Nominee Trust, proceeded as the sole plaintiff in the case.

The parties tried the case before me on October 7, 10, and 29, 2008. Court reporter Pamela St. Amand was sworn to transcribe the testimony for the first two days of trial, the transcripts of which were filed on October 30, 2008. A view of the locus was taken in the presence of counsel and several of the parties on October 10, 2008. Court reporter Karen Smith was sworn to transcribe the testimony for the third day of trial, and that transcript was filed on November 21, 2008. The exhibits which the parties introduced into evidence are as reflected in the filed transcripts, and those exhibits are incorporated into this decision for purposes of any appeal. The court suspended the trial after the taking of evidence concluded on the third day, and directed the parties to await the filing of the transcripts and thereafter to file post-trial written submissions, including legal memoranda and suggested findings of fact and rulings of law in advance of closing arguments.

On December 22, 2008, the parties, by their counsel, filed Posttrial Briefs and Proposed Findings of Facts and Rulings of Law. On December 29, 2008, Plaintiff wrote a letter to the court objecting to an aspect of Defendants submissions. Defendants Posttrial Brief had included a contention that the record easement at issue in this case had either never arisen, or had become extinguished, as a matter of record title, based upon unity of title to the disputed way and the benefitted land. Plaintiff objected to this position being asserted based, in large part, on Defendants failure to raise it earlier in the proceedings.

The contentions of the parties regarding the availability to the Defendants of their claim that the disputed easement is, as a matter of the record title to the way and the benefitted land, no longer legally viable, has led to subsequent orders by the court to address this question, to the filing of supplemental post-trial briefs, to further motions to amend the pleadings to address these contentions, and to further hearings and orders by the court.

On November 5, 2009, Defendants wrote a letter to the court responding to Plaintiffs objection. On January 20, 2009, this court ordered the parties to complete supplemental posttrial briefing on that issue. Plaintiff submitted a Supplemental Posttrial Brief on February 3, 2009. Defendants submitted a Supplemental Posttrial Brief on February 17, 2009. Closing arguments were heard on March 27, 2009. The court reporter, previously sworn, continued to transcribe the proceedings, and filed a transcript on April 22, 2009.

On January 11, 2010 the court issued an order requesting an offer of proof from Plaintiff, as to what additional evidence Plaintiff would provide if the court were to reopen the record and allow the Defendants claim of extinguishment by unity of title to be heard. Plaintiff responded on February 8, 2010, and Defendants filed their reply on February 22, 2010.

In April, 2010, Plaintiff moved to amend the pleadings to respond to the evidence, and the court, after reviewing Defendants opposition, held a hearing on May 4, 2010, at which the court made a number of rulings, all as reflected in the orders then entered on the docket. Among other things, the court allowed the requested amended complaint to be filed, and directed the filing of supplemental memoranda and other submissions. The court ruled that the assertion by Defendants, that the easement in dispute failed as a matter of record title (including as a result of the claimed commonality of the title to the way and to the land benefitted), while not advertised with great clarity in the case as pleaded prior to trial, ought, in the interests of justice, be considered by the court. Given the possibility that Plaintiff might have been surprised by the belated full-blown assertion of this theory by Defendants, the court inquired whether the Plaintiff would seek to reopen the evidence to support the new theories of easement by implication and estoppel she sought to press in the amended complaint. Counsel for Plaintiff declined to seek to introduce additional evidence, but requested and received leave to brief further in light of these alternative theories. Plaintiff considered the evidence already received sufficient to support her claims of easement by implication and estoppel, on which she would rely should the court side with Defendants on their view that the disputed 1911 record easement had failed or been lost as a result of the record title to the land involved. The court also reserved the opportunity to award Plaintiff some of her legal fees in connection with need to file this additional memorandum. These supplemental briefs and affidavits have been made by counsel and considered by the court.

BACKGROUND

On all the testimony, exhibits, stipulations, and other evidence properly introduced at trial or otherwise before me, and the reasonable inferences I draw therefrom, and taking into account the pleadings, and the memoranda and the arguments of the parties, I find the following facts and rule as follows:

Chain of Title in Eagles Nest Road

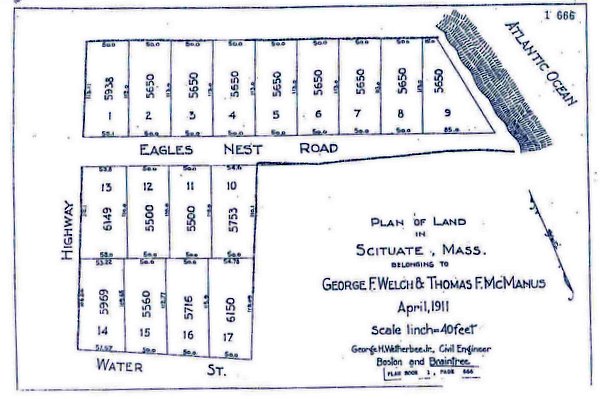

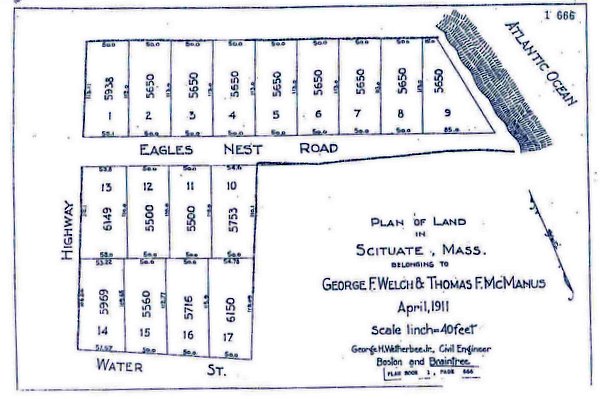

Eagles Nest Road was laid out as a private way in December of 1911, when George F. Welch and Thomas F. McManus recorded a plan dividing into lots certain property they owned on the high bluff, overlooking the Atlantic Ocean to the east, known as Third Cliff in Scituate, Massachusetts. The division plan (the 1911 Plan), which is entitled Plan of Land in Scituate, Mass. belonging to George F. Welch and Thomas F. McManus dated April 1911 and prepared by George H. Wetherbee Jr., Civil Engineer, is recorded in the Plymouth County Registry of Deeds (Registry) in Plan Book 1 at Page 666. The 1911 Plan depicts a division of the land owned by Welch and McManus into seventeen (17) lots with areas approximately 5,000 to 6,000 square feet each. A copy of the 1911 Plan is attached to this decision. The 1911 Plan shows the Atlantic Ocean to the east of the land on the plan. The ocean is depicted as lying beyond a strip of land separating the easterly boundary of Lot 9 (an unbending diagonal line oriented roughly north to south and parallel to the indication of the ocean drawn on the plan). Between the easterly boundary of Lot 9 and the ocean lies this strip of land, then cross-hatching intended to depict a slope or ramped decline leading to the beach and waters edge below. The 1911 Plan also shows an undimensioned but uniform width for Eagles Nest Road beginning from the Highway on the west, heading east to about the easterly line of Lot 4. As Eagles Nest Road proceeds further east from there, its width, again undimensioned on the 1911 Plan, is shown on it as tapering down (as it follows a stone wall along Eagle Nest Roads southern sideline) from that point heading towards the water.

The land shown on the 1911 Plan, which consists of approximately 2.75 acres, was acquired by George F. Welch pursuant to a deed dated April 13, 1911 from John Podolske, as Administrator of the Estate of John Boylen, which is recorded in the Registry in Book 1086, at Page 1. Five days after he purchased the land, George Welch conveyed an undivided one-half interest in the land to Thomas F. McManus pursuant to a quitclaim deed dated April 18, 1911, which is recorded in the Registry in Book 1086, at Page 2.

At the time they recorded the 1911 Plan, Welch and McManus conveyed lots 1 through 9 shown on the 1911 Plan (all the land on the northern side of Eagles Nest Road), consisting of approximately 51,138 square feet of land, to George Kingsbury pursuant to a warranty deed (the 1911 Deed) dated December 23, 1911, which is recorded in the Registry at Book 1109, Page 143. The 1911 Deed also states that in addition to lots 1 through 9, Welch and McManus also conveyed to Kingsbury:

a right of way to and from said lots over Eagles Nest Road as shown on said plan, said Eagles Nest Road to be forever left open for the purpose of travel, together with the right of way over said Cliff and Beach easterly of said lot to the Sea.

It is this language which constitutes the disputed record easement central to this litigation.

All of the land on the northerly side of Eagles Nest Road conveyed to Kingsbury by Welch and McManus (and an additional house lot elsewhere) was conveyed in a Mortgage from Kingsbury to Welch and McManus dated December 23, 1911 (the same date as the 1911 Deed) securing indebtedness in the amount of $1,900.00; the 1911 Mortgage was recorded with the Registry at Book 1109, Page 145, immediately following the recording of the 1911 Deed. The Mortgage granted by Kingsbury to Welch and McManus specifically included the land described in the 1911 Deed and all the privileges and appurtenances thereto. The Mortgage included partial release language by which the mortgagees agreed to release individual lots in exchange for stated amounts. For the mortgaged lots numbered one to nine on the 1911 Plan lying north of Eagles Nest Road, the partial release was to cost, per lot, one-ninth of $1,600.

By deed from Welch and McManus to Kingsbury dated June 24, 1919, which is recorded in the Registry at Book 1329, Page 60, Welch and McManus expressly conveyed the fee in the eastern portion of Eagles Nest Road adjacent to Lots 5 through 9 on the 1911 Plan to George Kingsbury.

The record before the court does not include the history of the title between 1911 and 1968. The parties have stipulated that all the land on the northern side of Eagles Nest Road was held in common ownership from 1911 until 1968, when Lots 1 through 9 were conveyed by Evelina M. Knott to Whitfield Potter and Adele Potter, as husband and wife, pursuant to a deed dated October 1, 1968.

On November 22, 1971, Whitfield Potter and Adele Potter, as husband and wife, conveyed Lots 1 and 2 shown on the 1911 Plan (located the most westerly of the nine lots, just at the road shown as the highway on that plan, and today Gilson Road) to Richard T. Caldwell and Joanne S. Caldwell, as husband and wife, pursuant to a deed recorded in the Registry at Book 3730, Page 60. Lots 1 and 2 on the 1911 Plan are commonly known as 141 Gilson Road, continue to be held in common ownership, and are currently owned by David L. Hackbarth and Deborah A. Hackbarth pursuant to a quitclaim deed dated August 28, 2003.

By deed dated May 22, 1972, Whitfield Potter and Adele Potter, as husband and wife, conveyed Lots 3, 4, and 5 shown on the 1911 Plan to Peter J. Murphy and Katherine T. Murphy, as husband and wife, pursuant to a quitclaim deed recorded in the Plymouth County Registry of Deeds at Book 3780, Page 719.

Since 1972, Lots 3, 4 and 5, which are commonly known at 3 Eagles Nest Road, have been held in common ownership and are now owned by plaintiff Elizabeth A. Murphy, as trustee of the Three Eagles Nest Road Nominee Trust, u/d/t dated January 2, 2002, recorded in the Registry at Book 22549, page 265, pursuant to a quitclaim deed dated January 2, 2002, which is recorded in the Registry at Book 22549, page 271.

Lots 6, 7, 8 and 9 on the 1911 Plan were retained by Whitfield and Adele Potter and then conveyed to John H. Trefrey, Jr. and Phyllis M. Trefrey, as husband and wife, pursuant to a quitclaim deed dated November 2, 1973, recorded in the Registry at Book 3947, Page 580.

Between 1973 and 2000, Lots 6, 7, 8 and 9, which are commonly known as 15 Eagles Nest Road, were held by members of the Trefrey family. Pursuant to a deed dated November 28, 2000, which is recorded in the Registry at Book 19106, Page 39, Carol J. Mack and John H. Trefrey, III conveyed Lots 6, 7, 8, and 9 to the Conways. The conveyance from the Trefreys to the Conways is also set out in a Confirmatory Deed dated November 25, 2003, from Carol J. Mack and John H. Trefrey, III to the Conways, which is recorded in the Registry at Book 27216, Page 115.

By operation of M.G.L. c. 183, s 58, the Conways own the fee in the entire width of Eagles Nest Road, as shown on the 1911 Plan, that is adjacent to the southerly side of Lots 6, 7, 8, and 9 on the 1911 Plan. The parties have stipulated that, according to the record title, the portion of Eagles Nest Road adjacent to the Conway premises is subject to the express easement for the benefit of the Murphy premises as described in the 1911 Deed.

Evolution of Third Cliff

Eagles Nest Road ends at Third Cliff, which slopes steeply downward toward what is now a sea wall located at the bottom of the cliff. This sea wall, which is approximately twenty feet high, was constructed by the Town of Scituate and the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers after the destructive blizzard of 1978 and runs the entire length of Third Cliff. Beyond the sea wall, there is a rocky intertidal area that is slightly exposed at low tide. At high tide, the Atlantic Ocean covers this area and the bottom third of the sea wall. The cliff itself is densely vegetated.

Prior to the installation of this sea wall, Third Cliff was in a state of continual natural erosion. The erosion of sand and sediment from the cliff created a coastal beach below the cliff. This beach existed when the 1911 Plan was prepared and Eagles Nest Road first was laid out. At this time, there was a far more gradual (than now) sloping sandy incline running from the sandy beach at the waters edge up to the top of the cliff. Also at this time, there were a number of staircases which existed along Third Cliff, connecting its top with the sandy expanse of beach below, and which permitted relatively simple access from the top of the cliff to the beach. None of these staircases were located in the immediate vicinity of Eagles Nest Road.

The Town of Scituate, seeking to prevent further erosion of the cliff, began in the 1930s to install protective masonry rip-rap at the bottom of the cliff. Over the decades that followed, officials took further measures to guard the bluff of Third Cliff from loss to tidal action by adding more rip-rap. The effect of the installation of rip-rap, and the eventual construction of the sea wall after the 1978 blizzard, was to eliminate completely the coastal beach below Eagles Nest Road. The anti-erosion measures have not completely prevented erosion from occurring. In high winds and storms, the unstable cliff above the revetment still occasionally experiences slides. In the past century, the surface of Third Cliff has eroded a distance of fifteen to twenty feet.

Historic Use of Easement Area

Eagles Nest Road is a dead end private way which runs from Gilson Road eastward toward Third Cliff. The easement area in dispute consists of the eastern portion of Eagles Nest Road that abuts Defendants property at 15 Eagles Nest Road.

Plaintiff Elizabeth Murphy and her family moved to a dwelling at 6 Eagles Nest Road, on the southern side of the street, in 1964. In 1972, the Murphys purchased land on the northern side of the street, where 3 Eagles Nest Road now is located. Between 1972 and 1987, the Murphys kept this land on the northern side of the road vacant, unbuilt upon, an open field. In 1987, the Murphys began construction of their home at 3 Eagles Nest Road. In 1988, the new house completed, the Murphys moved to 3 Eagles Nest Road. Murphy family members did not occupy the 3 Eagles Nest Road house for approximately six years, from 1996 until 2002. Peter J. Murphy, the current Plaintiffs father, remarried in 1996 and moved to the home of his new wife elsewhere in Scituate. Elizabeth Murphy took up residence at 3 Eagles Nest Road part time in around 2002. She resides in Florida. Other members of the family have resided there on and off during this time frame as well.

In 1964, the disputed easement area consisted of a grassy unpaved road separated from the land to the north by a wooden fence. That fence existed until the early 1970s, when it was taken down. The Murphy family made occasional use, within the appropriate seasons, of the easement area by riding bikes along it, playing sports along it, walking along it in groups to take in a view of the ocean, posing in it for family photographs with the ocean as a backdrop, and transporting wheelbarrows of yard waste across it to the edge of the cliff. The Murphys, sometimes accompanied by guests and other neighbors, at times made use of the easement area in small groups. Adults sometimes walked four or five abreast along the road. Children rode their bikes along the length of the road in groups of three or four. The area was not used for parking, and only on a very few rare occasions did a vehicle travel over the easement area. Initially, while they resided at 6 Eagles Nest Road, and mostly if not entirely prior to the 1978 blizzard and the construction of the revetment, some adventurous members of the Murphy family on limited occasions may have used the easement area to reach the Cliff, go over the Cliff, and dangerously climb down the side of the Cliff, traversing the steep slope to access the ocean and intertidal area exposed there at low tide. The frequency of that use declined as the children got older and the Cliff continued to destabilize, and I find that, at least until the time this dispute developed and litigation ensued, there was little if any such use made by the Murphy family members, or anyone else, for that matter. In more recent decades, the most frequent use the Murphys made of the easement area was that of walking along it to take in the view of the water.

Current Status of Easement Area

Since purchasing their land in 2000, and improving that land north of the disputed area with a large new residence and related improvements, the Defendants have made changes to the easement area itself. The Defendants have installed a brick driveway, mechanical features, trees, shrubs, and other landscaping features in the easement area. The mechanical features include an auxiliary generator and a pool filter, each installed upon concrete pads. The trees include four new pine trees, planted across the road by the Defendants. This was done, I find, to discourage others from walking on their property and to protect the Defendants privacy. Defendants occasionally park cars in the easement area. A narrow footpath remains along the southern portion of the easement area. By using this path, Plaintiff can, with some difficulty, traverse the easement area. It now is not possible to walk in a group abreast or to wheel a wheelchair along the easement area, given the limited width of the path provided.

DISCUSSION

The Claimed Ineffectiveness of the Easement Due to Unity of Title

In deciding the case, I first turn to the issue which consumed much of the parties and the courts attention after the taking of evidence at trial concluded: the assertion by the Conways that the purported record title right of easement, set out in the 1911 Deed, in fact established no record right of easement in the disputed area which benefits the 3 Eagles Nest Road parcel. The Defendants claim that, as matter of record title, no such easement ever arose, given the words and chronology of the relevant conveyancing documents.

Defendants rely on the fact, not in dispute, that the fee in the disputed area at Eagle Nest Roads eastern end was in Kingsbury at the same time as he acquired title to Lots 1 through 9 on the 1911 Plan by virtue of the 1911 Deed. Because Kingsbury received the fee to this strip, the Conways say, despite the words used in the deed, there never was an easement created. This, Defendants say, is the legal consequence of the state of title at the time. Because he owned both the burdened land and that benefitted by the easement language, there was effectively no easement which ever arose, because a purported easement to use one owns land is a legal nullity. On consideration of the facts as I find them to be, however, I conclude that this argument cannot prevail.

It is true that [a]n easement is an interest in land which grants to one person the right to use or enjoy land owned by another. Commercial Wharf East Condominium Assn. v. Waterfront Parking Corp., 407 Mass. 123 , 133 (1990). It also is true that courts have applied this fundamental principle to decide that, in appropriate cases, the unity of title--in one owner--of the fee simple ownership of both burdened and benefitted parcels may compel the conclusion that no easement exists. Massachusetts courts have recognized [this] ... doctrine of merger at least since the mid-nineteenth century. Busalacchi v. McCabe, 71 Mass. App. Ct. 493 , 497 (2008). In Cheever v. Graves, 32 Mass. App. Ct. 601 , 606 (1992) the Appeals Court concluded that a trial judge erred in determining that no merger had taken place so as to extinguish an easement. [I]n order to extinguish an easement by merger, a unity of title must have come into existence in the same person.... [An owner] cannot have an easement in its own estate in fee. Id., quoting York Realty, Inc. v. Williams, 315 Mass. 287 , 289 (1943). See also Krinsky v. Hoffman, 326 Mass. 683 , 687 (1951).

However, the courts have been reluctant to find that a record easement fails (or later becomes extinguished) because there is a common title to the benefitted and burdened lands, unless the common fee ownership is emphatically in the same holder. The courts considering these claims of unity of title and merger are concerned that there not be other record title holders interested in the benefit of the easement, who might depend on the easements existence in the land records for their own purposes. Busalacchi, 71 Mass. App. Ct. at 497-498.

In this case, the record evidence sets up just such a circumstance, and prevents a ruling that the easement is not viable on unity of title grounds. Here, the 1911 Deed containing the challenged record easement was executed and recorded simultaneously with a mortgage to Welch and McManus. This 1911 Mortgage was a purchase money mortgage, securing to the mortgagees the repayment by Kingsbury to them of the funds they had lent to him to facilitate his acquisition of ten lots, including the nine north of Eagles Nest Road. Welch and McManus as mortgagees had an interest in the appurtenant rights to use that road. Those rights were part of both their deed to Kingsbury, and his mortgage back to them. They needed the rights to use the road should they be required to take back the title to the conveyed land--if the mortgages covenants were to be breached.

Our courts have found that the presence of a mortgage can fend off a determination that an easement has failed due to merger or unity of title. See Ritger v. Parker, 62 Mass. 145 , 8 Cush. 145 (1851); Murphy v. Olsen, 63 Mass. App. Ct. 417 , 420 n.12 (2005). It is not clear to me from the cases that as an absolute rule, the mere giving of a mortgage of the land of the common owner will always mean that any easement over the commonly-owned land lacks force. Some of the cases suggest that it is not the mortgage alone which saves the easement, but the fact that the rights held under the mortgage may have been less than monolithic.

Thus, when there are two mortgages, covering multiple parcels, which secure different obligations, rendering it possible that some of the mortgaged land might be foreclosed separately from the rest, the cases certainly do see in that scenario a reason not to find merger and termination of the easement. That is effectively what happened in Ritger. There there were two mortgages which, though held by the same person, Mrs. Gardner, were defeasible upon different conditions, namely the payment of distinct debts. For this reason, there was a genuine possibility that there might be a foreclosure which would change title to some--but not all--of the land involved. When that happened, the need for the easement might well become palpable. The presence of that possibility, of foreclosure as to some but not all of the land involved, was what kept the easement in Ritger from failing on unity of title grounds. Notwithstanding that, as far as the mortgagor is concerned, there was a unified title in all of the lands subject to the two mortgages, the independent rights of the mortgagee under the multiple mortgages kept the easement from failing. To the extent that some of the cases suggest a broader rule--that the grant of any mortgage at all will save an easement which otherwise would fail as a result of merger--those cases seem to say that in dicta. See, e.g., Murphy v. Olsen, supra at n. 12.

In the case before me, it is clear that the principle of Ritger is directly applicable, and that the grant of the 1911 Mortgage did prevent the challenged easement from failing ab initio. The mortgage was a purchase money mortgage, given and recorded simultaneously with the conveyance to Kingsbury. It therefore is not correct to treat him as having held title to all the land (both the lots and the fee of the way) in unified title at any time free of the mortgage. Kingsbury got his title and mortgaged all of it as part of the same transaction.

Although Kingsbury gave but one mortgage back to his grantors, it is significant that this one mortgage came with rights of partial release of individual lots. Kingsbury had the power to sell off individual lots, and to free each of them of the mortgage held by Welch and McManus, by paying a fixed sum out of the sale proceeds each lot presumably would generate. Under this agreed arrangement, it certainly would have been possible to have the mortgagees foreclose as to some but not all of the original nine lots. It also is certainly possible that, in such a case, the third-party buyers of the individually-sold lots would have been conveyed, along with the lot itself, the fee in the adjoining strip of the way nearest their lots. The provisions of common law that form the genesis for the later-enacted derelict fee statute, G.L. c. 183, §58, would have produced such a result, and the partial release might have lifted the mortgage not only from the lot, but also from the fee in the way so conveyed. This would have left the mortgagees, and those taking title to the lots remaining subject to the mortgage at the time of a foreclosure, in genuine need of easement rights to pass over the portions of Eagles Nest Road which, as a result of the partial releases, no longer were subject to the mortgage. This reality of the 1911 Mortgage transaction, with its firm undertaking for partial releases of the lots later individually sold off, defeats Defendants unity of title argument, and requires the conclusion that there was no failure of the easement from the time it was established in 1911.

I find and rule that the easement expressly set out in the 1911 Deed did not fail from the very start based on common ownership by Kingsbury of the fee of the way and the nine lots. [Note 1]

The Meaning and Scope of the Easement Set Out in the 1911 Deed

Having determined that the easement set out in the 1911 Deed remains in force, I need to resolve what its meaning and scope is, and how it might be used by Plaintiff today. In deciding that the record easement was not prevented from arising (and was not later lost) as a result of any unity of title, my focus is on the originally granted easement. To the extent it might have been necessary, given the amended complaint, to consider the prospect of some implied easement or easement by estoppel having arisen later, for example when the 3 Eagles Nest Road parcel was set off to the Murphy family in 1972, that need no longer exists, given that the 1911 Deed easement did not fail at the outset and is firmly established in the record title. My task is to understand the purpose and reach of the originally granted easement, using the standards enunciated in the cases.

In carrying out this endeavor, a court looks primarily to the language of the grant, construed when necessary in light of the attendant circumstances in existence at the time of the easements creation. Sheftel v. Lebel, 44 Mass. App. Ct. 175 , 179 (1998); Bergh v. Hines, 44 Mass. App. Ct. 590 , 592 (1998): When created by conveyance, the grant... must be construed with reference to all terms and the then existing conditions so far as they are illuminating.... The relevant circumstances to which the court may refer include relevant uses made of the servient estate at the time of, or prior to the instrument creating the easement. Pion v. Dwight, 11 Mass. App. Ct. 406 , 412 (1981).

My inquiry proceeds from the language of the grant itself. The grant is of a right of way to and from said lots over Eagles Nest Road as shown on said plan, said Eagles Nest Road to be forever left open for the purpose of travel, together with the right of way over said Cliff and Beach easterly of said lot to the Sea. As the parties appear to agree, there are two elements to this right. The first is a right of way to and from the lots for travel. To the extent this right is understood to mean that each house lot now on Eagles Nest Road, including those of the Plaintiff and the Defendants, have the full right to use the road to pass and repass from those lots to and from Gilson Road, the public way to the west, that much is undisputed.

It is the second component of the 1911 language which is in controversy. The relevant words are that there is also a right of way over said Cliff and Beach easterly of said lot to the Sea. On these words themselves, the meaning of the disputed provisions strongly appears to be that the right is one of way to get over the Cliff, then over the Beach, to reach the described destination, the Sea. The language means that owners of the nine lots on the 1911 Plan may use the depicted Eagles Nest Road, including its tapering eastern end, as a way to get to that destination, to the Sea, over a route which requires the user to traverse the Cliff and then transit the Beach lying in front of the ocean. I find and rule that this is what the words of the grant say and mean. This is the proper interpretation of the meaning of the words employed by the parties to the original creative instrument. They envisioned a right which would allow transit down the lane, over the peak of the Cliff, continuing down the sloping sands of what was then the incline of the Cliff, connecting its top to the sandy expanse of beach at the bottom, as a way to get to, and into, the salt water.

This interpretation of the language is based upon its plain meaning, which I find to be unambiguous; this interpretation also is fully consonant with the circumstances I find existed in this location in 1911, at the time of the grant. When the lots were created and first sold, the landscape of the Cliff and the waterfront was far different, as a practical matter, than what exists today. The evidence convinces me that in the first decades of the prior century there was a meaningful opportunity to pass over the peak of Third Cliff, descend down a slope of sand at a tolerable angle, and then land on a beach of sand which was broad and open enough to use for traditional beach walking, sunbathing and swimming purposes. There are photographs of this vintage which show this to be the case, and I so find. The beach as it then existed was not only wide enough for picnicking and recreational and leisure activities on the sand between the base of the slope and the edge of the water, but also was feasibly accessible by pedestrians willing to pass down the sandy slope to reach the beach. The easement surely was established to recognize that the owners of houses along the new road would want to use it to pass on foot in an easterly direction to reach the head of the Cliff, and then continue on, over the peak, and down the slope, to enjoy the pleasant features of the sandy beach below.

Nothing suggests to me that this right was a right for vehicular passage. I do not find there to have been any such use made of the particular route at issue in this case, nor at any of the other nearby access points over Third Cliff to the beach below which were present during the same period. While there is some indication that there was at times some boating which took place off the beach as part of the general recreational use of the waterfront, I find no support in the evidence I credit for the conclusion that boats were deployed over Third Cliff down the sandy slope to reach the beach. I can only conclude that the boating which took place was in vessels which arrived at the beach over the water after having been launched elsewhere, and that the pedestrians who came over the Cliff and down the slope did so without boats, and without any vehicular accompaniment.

I note that at this time there were, elsewhere up and down Third Cliff, wooden stairs which facilitated access down and, perhaps more importantly, up the slope extending from the top of the cliff to the sand of the level beach below. While I conclude, in light of this evidence, that the right in dispute in this case might have contemplated use of stairs to facilitate access to and from the oceanfront beach, I do not find that the right was dependent on stairs being installed. Judging from the evidence as best as I can, I find that in 1911 it was possible, if somewhat less than fully convenient, to traverse the slope as it then existed without stairs, and that the record right envisioned that use, and also the use of any stairs should they be installed later to improve the quality of passage over the Cliff.

I do not find that the right set out in the 1911 Deed encompassed a distinct property right to use the eastern tapering portion of Eagles Nest Road to gain a view of the ocean from the higher elevation. While of course views of the water would have been openly available to those who walked the route to reach and then transit over the Cliff, the attainment of views was incidental, and not part of the right granted in the deed. This is so because the right in the deed is a specific right--a right of way. A right of way connotes use of the burdened land for passage, and not for other prolonged stops to take in the vistas or to engage in recreational activities along the route. The record right is the right to get somewhere, and not to plant oneself down in the midst of the pathway. See Carlin v. Cohen, 73 Mass. App. Ct. 106 , 111 (2008), pointing out that an easement is created to serve a particular objective (citing to M.P.M. Builders, LLC v. Dwyer, 442 Mass. 87 , 92-93 (2004)) and that, where a right of way to reach a beach is concerned, [a]ccess to a view was not a purpose for which the easement was granted. Moreover, there is nothing in the evidence which I credit as the trier of fact which leads me to find that at the time the grant was made there was any use being made or contemplated which would have led to the creation of a property right to take in the views, or to otherwise conduct recreation activities of any sort, on the way to, and on the peak of, the Cliff.

I conclude that the easement at issue in this case was for the specific passage purposes I have identified, and not for other broader and far-reaching purposes.

The Vitality Today of the Record Easement as a Consequence of Fundamental Changes in the Condition of the Property

Having determined the meaning, purpose, and scope of the easement as it was created and continues of record to burden the Defendants land, I must decide whether, given the fundamental changes that have taken place in this location since the easement first arose, it continues to be in force. Defendants contend, and Plaintiff disputes, that the purpose of the easement has been rendered unattainable due to the dramatic and lasting alteration in the physical features of the Cliff, and of the side of the bluff connecting the Cliff to the Sea below.

The evidence is overwhelming that the coastal beach over which the disputed easement provided a right of passage has ceased to exist, and is incapable of being reestablished. I so find. I also find that, as a result of prolonged and powerful natural forces over many decades, not only has the beach disappeared; there also has been a pronounced and material change in the location of the edge of the Cliff and in the route formerly used for passage from the top of the Cliff to the water below. The cumulative effects of decades of erosion, including not in the least the powerful and destructive impact of the blizzard in 1978, have turned the formerly broad usable beach and the sloping sandy side of Third Cliff in this vicinity into something fundamentally different. The top edge of the Cliff is pushed further back to the west. The side of the Cliff is now armored at its base by heavy rock revetment, and is so steep and dangerous as to effectively preclude transit over the side to reach that revetment. And once one were to reach the revetment, even were it possible to do so at all, there is effectively no beach beyond it. The ocean has consumed all of the former beach, and now charges at the revetment, the lower part of which is under water for much of the tidal cycle.

I conclude that these dramatic changes have resulted in the termination of the record 1911 easement. An easement is not to be undone because it has gone unused, nor simply because some of the granted rights may be less capable of convenient exercise. But the decisions of our courts instruct me that when an easement is granted for a particular purpose, it is to be used only for that purpose, and that, should the attainment of that purpose become impossible, the easement ought be treated judicially as no longer extant. In Makepeace Bros. v. Barnstable, 292 Mass. 518 , 525 (1935) the Supreme Judicial Court said that ...if an easement is stated to be for a particular purpose it is limited to the purpose stated. ... When a right in the nature of an easement is incapable of being exercised for the purpose for which it was created the right is considered to be extinguished.

The evidence shows me that the limited purposes of the 1911 easement are now incapable of exercise. It is no longer possible, as it earlier was, to use the eastern end of Eagles Nest Road to pass to the top of Third Cliff, over the sandy slope that formerly led from there to the beach below, then over the beach below to the sea. I find that, given the current physical conditions, no form of passage over the top of the Cliff can take place in any meaningful, safe, or acceptable way. Indeed, the Murphy family appears in this litigation to concede as much. There is no way the route for which the 1911 Deeds easement was put in place can be used for the contemplated purpose today. In reaching this conclusion, I have considered the testimony of experts and other witnesses concerning the possibility of today obtaining approvals to put in place some form of stairs or other improvements to be used to navigate down the side of the Cliff to reach the revetment beneath, and I find that there simply is no likelihood of that happening. I decide that the limited purpose of the record easement is frustrated entirely, and that it no longer has any vitality.

That the Plaintiff might wish to do something short of what the record easement provided, as, for example, to use the eastern end of Eagles Nest Road to reach the promontory of the Cliff as it now exists, and to use that platform as a recreational or viewing platform, is, however understandable, for reasons previously discussed not something which the easement allows. These fallback uses of the Defendants land were never part of the rights granted, and cannot be authorized by the court as a substitute for those which were, and which now have become incapable of exercise. Given the presence of the 1911 Deed easement in the record title and the posture of this case, Plaintiffs claims in this litigation are limited to those arising under the record right. She is not able to set up rights by implication, estoppel, based on use, or on other theories not derived from the right granted in 1911. The rights she is able to claim in this litigation are the record rights, and those have been extinguished for the reasons set forth in this decision. [Note 2]

The judgment I will direct be entered will establish that the Defendants hold their title to their land, including the eastern end of Eagles Nest Road, free of any easement rights of the Plaintiff, including, without limitation, the rights set forth in the 1911 Deed. [Note 3]

Judgment accordingly.

Even were I to consider those contentions by the Plaintiff, however, they would not result in any different outcome. The easement by estoppel argument--that the Plaintiff has rights to use the entirety of Eagles Nest Road for passage, including to the top of the Cliff so she can take in the view and engage in recreational activities there, is a position not supported by the cases; they only establish, in the absence of an express right, a right by estoppel for passage along the road shown on the plan to reach the public way. See, e.g., Murphy v. Mart Realty of Brockton, Inc., 348 Mass. 675 (1965). Plaintiffs claimed rights do not fall at all within the rubric of these decisions.

There also is no basis on the evidence I heard for recognition of an easement by implication. First, the establishment of the implied easement right is belied by the express easement, whose words do not support the uses now claimed by the Plaintiff. The cases on this theory would look to the uses being made of the burdened property for the benefit of the Plaintiffs land at 3 Eagles Nest Road at the time of severance. See, e.g., Mt. Holyoke Realty Corp. v. Holyoke Realty Corp., 284 Mass. 100 , 104 (1933). Under these cases, the court would see if, despite silence in the relevant recorded instruments, there was an open use of the burdened land then ongoing which was then being carried out to the benefit of the land conveyed, and that the claimed servitude was reasonably necessary for the benefit of that land. Id. Here, of course, no use at all of the Plaintiffs land was being made at the time of severance, for the land was vacant and remained so for many years until a house finally was built in the late 1980's. I also could not find that the rights claimed in this litigation qualify as reasonably necessary for the benefit of Plaintiffs land. While I appreciate the test is reasonable, as opposed to absolute, necessity, and that possession by Plaintiff of the rights she claims would enhance her enjoyment of the property to some modest degree, I cannot say that these rights would be reasonably necessary within the meaning of the cases. I also cannot find that the presumed intention of the parties to the conveyance by the Potters to the Murphy family in 1972 was that the rights now sought by Plaintiff were to be included, even though the deed did not grant those rights. It is that presumed intention which is the required source of judicial recognition of implied easement rights, when the deeds do not contain the rights expressly. See, e.g., Reagan v. Brissey, 446 Mass. 452 , 458 (2006)

Although the Plaintiff does not have the right to establish her claimed easements on theories of estoppel or implication, those rights would not have been found in her favor even were she able to pursue them.

The court now has ruled that there was no invalidity or loss of the record easement based on unity of title or merger. As a result, there has been no need for the court to entertain the alternative theories of easement by estoppel and by implication which Plaintiff was forced to brief to deal with the Defendants merger contention. Nevertheless, I consider it fair and just that some reasonable portion of the legal expense to produce the brief last filed by Plaintiff, which presented her position on why the law would justify recognition of easements by either estoppel or implication, ought to be paid to Plaintiff by Defendants.

I have reviewed the affidavits filed on this point. I have considered the amended affidavit of Plaintiffs counsel, Mr. Mangiaratti, and the accompanying detailed billing statement. I conclude that much of the time reflected on this statement is not for work properly to be charged to the Defendants. A good deal of the time shown is for work done prior to, and otherwise not directly related to, the production of the last supplemental brief of the Plaintiff. And even some of the time which chronologically would fall in the time the supplemental memorandum was being prepared seems not reasonably close enough in substance to the direct work on the brief. Nevertheless, I do consider the hourly rates indicated fully justified given the experience of the involved attorneys. Plaintiffs lead counsel is highly experienced, competent, and well-regarded, and easily worth the rate he has indicated. Having considered the revised billing statement carefully, and discounted for work unrelated to, or not directly required to be performed in connection with the preparation of the supplemental memorandum, I find that the interests of fairness and justice require that the Defendants pay to the Plaintiffs their resulting reasonable legal fees in the amount of $4,900.00.

ELIZABETH A. MURPHY, Individually and as Trustee of the 3 Eagles Nest Road Nominee Trust; EDWARD OBRIEN; EILEEN O'BRIEN, EDWARD CORBO; VIRGINIA DOHERTY; and PAUL KELLY v. KENNETH J. CONWAY and CAROL A. CONWAY, Individually and as Trustees of The Windmill Trust

ELIZABETH A. MURPHY, Individually and as Trustee of the 3 Eagles Nest Road Nominee Trust; EDWARD OBRIEN; EILEEN O'BRIEN, EDWARD CORBO; VIRGINIA DOHERTY; and PAUL KELLY v. KENNETH J. CONWAY and CAROL A. CONWAY, Individually and as Trustees of The Windmill Trust