Introduction

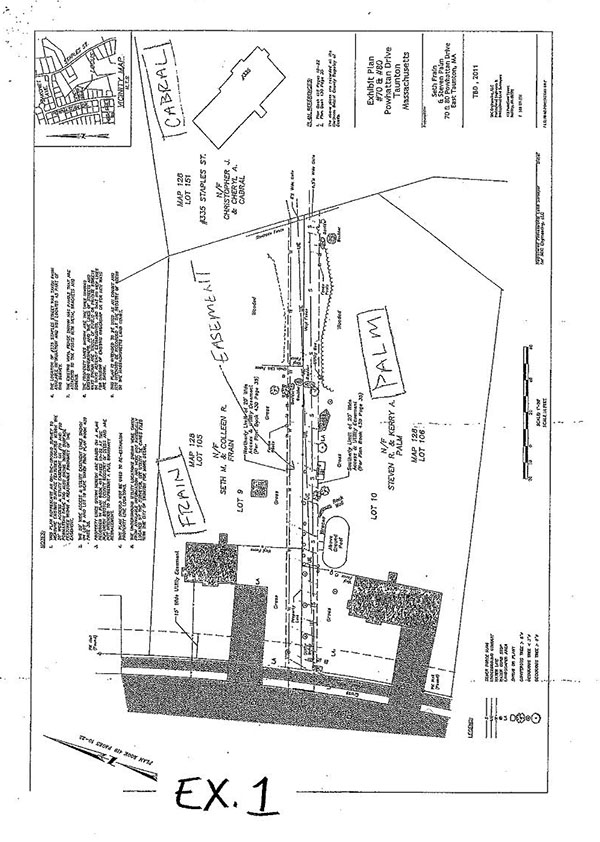

The defendants, Seth and Colleen Frain and Steven and Kerry Palm, own adjacent lots in the Powhattan Estates subdivision, both of which abut 335 Staples Street owned by the plaintiffs, Christopher and Cheryl Cabral. This case is a dispute over the scope of an express 20-wide easement extending from Powhattan Drive over the defendants properties to the rear of the Cabral lot. See Ex. 1 (attached). The easement is actually composed of two separate grants, one from the Frains and the other from the Palms, both made in October 2004 and each granting a 10-wide easement, intended to be used as a singular, 20-wide easement (the Frain/Palm easement), to Bruce Development Corp., the then-owner of 335 Staples Street. The language in the two grants is identical, and each convey[ed] a perpetual right

to pass and repass over the Frain and Palm properties. The recorded plan referenced in the instruments depicts and describes it as an access and utility easement. At the time the easement was granted in October 2004, there was no other means of access to 335 Staples Street.

Two years after those grants, when Bruce Development sought to construct a single- family home at 335 Staples Street, it secured a new means of access by way of a 20-wide easement off of Staples Street (the Staples Street easement) and built a driveway over that easement. Malloch Construction, which Bruce Development hired to develop 335 Staples Street, installed underground utilities in the Frain/Palm easement to service 335 Staples Street. When the installation was completed, Malloch Construction placed three large boulders across the entire width of the easement. The Frains and Palms have since installed fences, trees and bushes within the easement area.

The Cabrals brought this action, contending that these surface objects interfere with their rights to use the easement for access to the rear of their property and for maintenance of the underground utilities. The defendants, however, contend that the right to pass and repass over the Frain/Palm easement for access to 335 Staples Street was abandoned by Bruce Development before the Cabrals purchased the property. They further contend that the objects presently within the easement do not unreasonably interfere with the Cabrals right to maintain the underground utilities that service their property.

The parties cross-moved for summary judgment on these issues and, in a memorandum and order, this court (Long, J.) determined that the Frain/Palm easement was an easement appurtenant, not in gross, and thus did not terminate when Bruce Development sold 335 Staples Street to the Cabrals. See Memorandum and Order on the Parties Cross-Motions for Summary Judgment (Dec. 6, 2012). The present scope of the easement, however, could not be resolved on summary judgment since genuine disputes of material fact remained concerning Bruce Developments alleged abandonment of its right to pass and repass over the defendants properties. There were also factual disputes over whether the surface objects within the easement unreasonably interfered with the Cabrals ability to maintain their underground utilities.

The case was tried before me, jury-waived. Based on the testimony and exhibits admitted into evidence at trial, my assessment of the credibility, weight, and inferences to be drawn from that evidence, and as more fully set forth below, I find and rule as follows: (1) the right to pass and repass over the Frain/Palm easement for unrestricted access to the Cabral lot was definitively abandoned by the Cabrals predecessor owner, Bruce Development Corp., (2) the right to use the easement for utility purposes and, more particularly, to access and maintain the underground utilities presently there, and to add others if and when needed, remains; (3) the fence that runs down the center of the easement may remain in place since it does not presently interfere with the Cabrals right to maintain their utilities and is consistent with the policy of maximizing the beneficial use [of land] available to the landholder

. Martin v. Simmons Properties, LLC, 467 Mass. 1 , 14 (2014), (4) portions of the fence may be removed, as and when necessary to gain access to the underground utilities for repair or maintenance, (5) the various trees identified below and the three boulders must be removed as soon as practicable since these objects cannot be readily and quickly removed when utility-related access is needed.

Facts

These are the facts as I find them after trial.

In 2001, Bruce LLC obtained a G.L. c. 40B comprehensive special permit to develop the Powhattan Estates subdivision, a 150 lot development in Taunton. Bruce LLC was established as an offshoot of Bruce Development Corp. since an LLC was required for the comprehensive permit. James Salvo is a principal of both Bruce Development and Bruce LLC.

Bruce LLC retained Malloch Construction Company to develop the Powhattan Estates subdivision. Malloch has worked with Bruce Development for 20 years on various subdivisions. Malloch handled the zoning, permitting and construction of the Powhattan Estates subdivision.

Bruce LLC owned the real estate and supplied financing, but was basically an investor in this process. A Certificate of Authority executed by Bruce LLC on December 18, 2003 and recorded in the Bristol County (Northern) Registry of Deeds on January 9, 2004 at Book 13215, Page 104 authorized Mr. Malloch to sign all documents, excluding Deeds, and do all other acts necessary, pertaining to the sale of real estate in the developments including but not limited to Powhattan Estates in East Taunton

.

The Frains purchased 70 Powhattan Drive from Bruce LLC in October 2004. The Palms purchased their home at 80 Powhattan Drive from Bruce LLC in October 2004. Both are part of the Powhattan Estates subdivision. When Bruce LLC conveyed these properties to the Frains and Palms respectively, Bruce Development Corp. owned the vacant lot at 335 Staples Street located directly behind 70 and 80 Powhattan Drive. 335 Staples Street is not part of the Powhattan Estates subdivision plan. 335 Staples Street had sufficient frontage, but access to the lot from this frontage was blocked by wetlands.

As part of the sale of 70 and 80 Powhattan Drive, Mr. Malloch negotiated the terms of an easement with the Frains and Palms, respectively. In exchange for a $10,000 reduction in the purchase price of their homes, the Frains and Palms each granted Bruce Development Corp. a perpetual right and easement to pass and repass over their properties to 335 Staples Street. [Note 1] Easement, Palm to Bruce Development Corp., Bristol (North) Registry of Deeds, Book 14158, Page 13 (Oct. 14, 2004); Easement, Frain to Bruce Development Corp., Bristol (North) Registry of Deeds, Book 14162, Page 296 (Oct. 15, 2004). The purpose was to provide access to the now-Cabral property (335 Staples Street) and to put underground utilities for that house in it. The easements are each 10-wide and run from Powhattan Drive to the rear of 335 Staples Street. A recorded easement plan refers to the two, 10-wide easements as a single, Proposed 20-wide Access and Utility Easement. See Plan of Easement in Taunton, Massachusetts, Bristol (North) Registry of Deeds, Plan Book 430, Page 35 (Oct. 7, 2004).

Mr. Malloch handled the purchase and sale negotiations with the Frains and Palms. During these negotiations, he discussed the easements with them, telling them that they could use the portion of their properties burdened by the easement as part of their back yards so long as they did not interfere with the easement rights. He explained that the easement was needed for the installation of underground utilities that would serve 335 Staples Street, but the parties never discussed the pass and repass language contained in the easement grants. However, when the Frains and Palms purchased their properties, there was no other means of access to 335 Staples Street. A driveway over the Frain/Palm easement was never constructed because, as Mr. Malloch testified, the Taunton Zoning Board believed it would give the appearance of adding a new lot to the Powhattan Estates subdivision, which would have constituted a major change to the comprehensive permit requiring a new public hearing and because, as discussed below, driveway access to 335 Staples Street was ultimately obtained by easement from Staples Street itself.

Seth Frain and Steven Palm both testified that, from the time they moved into their homes in October 2004 until 2006, the easement area was heavily wooded. In 2005, Mr. Frain constructed a fence in his backyard that ran parallel to, but just outside the boundaries of the

easement. Around the same time, Mr. Palm constructed his own fence on his property, similarly outside the easement area. At the time these fences were constructed, the easement area remained wooded. The fences were constructed outside the easement area in case Malloch needed to bring trucks through the easement to build the house at 335 Staples Street.

In May 2006, Malloch Construction, acting on behalf of Bruce LLC, [Note 2] sent a letter to the Zoning Board requesting a revision to the approved subdivision plans showing the Frain/Palm easement. The letter states, [p]reviously, we had requested an access and utility easement in this same area for a driveway and utilities but withdrew this request. (emphasis in the original) The revision sought was to allow for a 20-wide utility easement between [the Frain and Palm properties], thereby eliminating the reference to access. Id. The letter states further that [t]he proposed utility easement will provide sewer and water to a lot with access to said lot [335 Staples Street] from Staples Street not the Powhattan Estates Subdivision. Id. The Zoning Board wrote back to Malloch in May 2006 approving the revision from an access and utility easement to simply a utility easement. The Frain/Palm easements themselves, however, were never changed and their language remained the same.

In June 2006, Malloch submitted an application for a variance to the Zoning Board to construct a single-family home on 335 Staples Street with access via an easement over the adjacent property at 325 Staples Street, not the Frain/Palm easement. A plan attached to the variance application shows that 325 Staples Street was owned by the Salvo Land Trust, whose principal, Joseph Salvo, also managed Bruce LLC and Bruce Development Corp. A more detailed variance plan showing 335 Staples Street and surrounding lots describes the Frain/Palm easement as only a utility easement, with no mention of access. See Variance Plan of Land in Taunton, Mass. (June 21, 2006). The Zoning Board granted the variance on July 27, 2006. On September 1, 2006, the Salvo Land Trust conveyed a 20wide access easement to Bruce Development Corp., granting the perpetual right to pass and repass over 325 Staples Street. See Easement, Salvo Land Trust, Inc. to Bruce Development Corp., Bristol County (North) Registry of Deeds, Book 16168, Page 217 (Sept. 1, 2006). This became the 335 Staples Street driveway.

Around the fall of 2006, Mr. Palm first noticed activity on the Frain/Palm easement. Malloch cleared the woods within the easement area, dug a trench, and utility lines (water, sewer, electric, telephone and cable) were installed to service 335 Staples Street. Once the utilities were installed, the trench was back filled and Malloch placed three, large boulders across the width of the easement to block vehicles from traveling over it. After the boulders were placed, the easement area was landscaped, loamed and seeded to blend with the rest of the lawn area in the Frain and Palm backyards. No construction vehicles ever traveled over the Frain/Palm easement during the construction of the Cabral home. As Mr. Malloch testified, if the easement was going to be used as a driveway, his company would have dug out all the subsoil and put in compacted gravel. That never happened. Instead, during the construction of the Cabral home, all access to 335 Staples Street came by way of the Staples Street easement over 325 Staples Street, which was owned by the Salvo Land Trust.

The Cabrals first visited 335 Staples Street in November 2006. The house was still under construction, but the Cabrals walked the grounds of the property with Sue Malloch, Mr. Mallochs sister, who was also the realtor for Bruce Development Corp. Mr. Cabral testified that he noticed the easement when he first visited the property, but did not ask Ms. Malloch about it. The easement was bordered on either side by the fences that the Frains and Palms had built, both of which ended a few feet before the boulders. At the time, there were no fences along the rear property line between the Frain and Palm properties and 335 Staples Street. The Cabrals visited the property a second time before signing the purchase and sale agreement in December 2006. This time, they toured the inside of the home. Mr. Cabral testified that there was a clear view of the easement area from the second floor window of the home. The only objects he recalled seeing in the easement were the boulders that had been placed there by Malloch Construction. He asked Ms. Malloch what this area was used for, and she explained that it was an easement that brought utilities to the home. Mr. Cabral testified that he understood it as it being my utility easement

. Use of the easement for access to 335 Staples Street was never discussed. When the Cabrals visited the property, they used the Staples Street easement for access. Bruce Development Corp. sold 335 Staples Street to the Cabrals in February 2007 and the Cabrals moved in shortly thereafter in March 2007.

From 2007 to 2009, the Cabrals, Frains and Palms had no disputes or discussions about the easement. In the spring or summer of 2009, Mr. Cabral approached the Palm children who were playing on the boulders and had left pieces of Styrofoam blocks in the easement. Mr. Cabral asked to speak with their mother, Ms. Palm, and explained to her that he wanted to cut the grass in the portion of the easement that extended from the boulders to the rear of his lot, but the Styrofoam blocks were in the way. [Note 3] They picked up the blocks together, and Mr. Cabral proceeded to cut the grass. Mr. Cabral mentioned to Ms. Palm that he was thinking of installing a gate across the width of the easement that could be opened when access was needed. [Note 4]

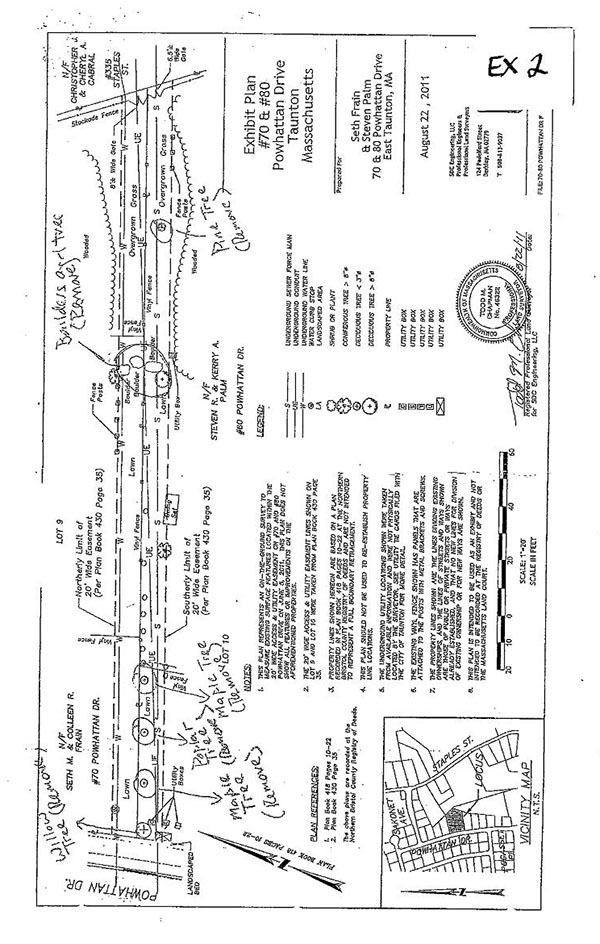

The next day, Mr. Palm came to the Cabrals back door and explained to Mr. Cabral that he owned the land burdened by the easement and was against Mr. Cabral constructing a gate within the easement area. A few days later, Mr. Palm retained a surveyor to survey the centerline of the easement, which is also the boundary between the Palm and Frain properties, and over the next few months, he built a vinyl fence running down the middle of the easement. The new fence ran between the boulders in the easement with one boulder on the Palm property to the south of the fence and two boulders on the Frain property on the northern side of the fence. See Ex. 2 (attached). The fences that the Palms and Frains built in 2005, which were located outside the easement area, were taken down. The Palms and Frains each constructed their own fences along their rear boundary lines separating their properties from the Cabral lot. [Note 5] After the fences were constructed, Mr. Palm planted shrubs and trees on his side of the easement.

The Cabrals filed this action for declaratory and injunctive relief, contending that they have an express easement for access to their property and for maintenance of the utilities within the easement. [Note 6] They allege that the surface objects in the easement materially interfere with their rights of access and maintenance of the underground utilities and must be removed. Following summary judgment, this court determined that the Frain/Palm easement was appurtenant to the Cabral property, but the present scope of the easement could not be fully resolved on summary judgment.

The agreed facts clearly demonstrate that the utility aspects of the easement remain, and the Cabrals have the right to maintain those utilities. But whether or not the right to pass and repass over the Frain/Palm easement had been abandoned could not be resolved on the summary judgment record. Furthermore, the question of whether any surface objects materially interfere with the Cabrals ability to maintain their utilities could not be determined on summary judgment.

Trial thus focused on those two issues: 1) whether the right of access to pass and repass over the easement had been abandoned by Bruce Development Corp. [Note 7], and 2) whether the objects within the easement unreasonably interfere with the Cabrals right to maintain their underground utilities.

Additional facts are discussed in the Discussion section below.

Discussion

Abandonment of the Right to Pass and Repass Over the Frain/Palm Easement for Access to the Cabral Lot

The express terms of the easement granted to Bruce Development Corp. by the Frains and Palms include a perpetual right

to pass and repass and the plan referenced in the instruments describes the easement as a 20-wide Access and Utility Easement. As Mr.

Malloch testified, the developers thought about using the Frain/Palm easement for a driveway to 335 Staples Street because, at the time of the easement grant, there was no other means of access to the lot and thus it could not be developed. At that time, the easement was of such importance that Bruce LLC conditioned the purchase and sale agreements for the Frain and Palm properties on their granting the access and utility easement to Bruce Development. Mr. Frain testified that he was aware there was a possibility that the easement would be used for access purposes and thus he made sure in 2005 to construct his initial fence outside the boundary of the easement. But the Frains and Palms now contend that the right to pass and repass for access was abandoned by Malloch Construction, acting on behalf of the easement holder, Bruce Development.

Abandonment is a question of intent, generally inferred from the easement holders actions or, in certain circumstances, inactions. See Sindler v. William M. Bailey Co., 348 Mass. 589 , 592 (1965); The 107 Manor Avenue LLC v. Fontanella, 74 Mass. App. Ct. 155 , 158 (2009) (failure to protest acts which are inconsistent with the existence of an easement, particularly where one had knowledge of the right to use the easement, permits an inference of abandonment). The party asserting abandonment carries the burden of proof. New York Cent.

R.R. Co. v. Swenson, 224 Mass. 88 , 92 (1916). Nonuse, by itself, does not prove abandonment. Cater v. Bednarek, 462 Mass. 523 , 528 (2012) (finding an easement valid in spite of a ninety- eight year period of nonuse by the dominant estate holder). The party claiming abandonment must show, in addition to nonuse, that the easement holder took affirmative action (or, as noted above, failed to take action in certain circumstances) evidencing either a present intent to relinquish the easement or a purpose inconsistent with its further existence. Lasell College v. Leonard, 32 Mass. App. Ct. 383 , 390 (1992) (internal citation omitted); The 107 Manor Ave. LLC, supra.

Here, the Frains and Palms established, through ample evidence, the easement holders intent to abandon the right to pass and repass over the Frain/Palm easement for access to the Cabral property. Nonuse was easily established from the uncontested testimony that the easement was never used for access purposes. As Mr. Malloch testified, no construction vehicles ever used the Frain/Palm easement during the construction of the Cabral home. Furthermore, the easement was never prepared to accommodate such traffic. The subsoil was never removed and the surface was never compacted with gravel. Although the express language of the easement grant contained a right of access, the easement was never used for that purpose, for two reasons: the Zoning Board was against it, and an alternate, better access driveway to 335 Staples Street (the Cabral lot) was found. As Mr. Malloch explained, the Zoning Board believed that putting a driveway on the easement would have constituted a major change to the comprehensive permit for the Powhattan Estates subdivision. Pursuing such a change would have come at significant financial cost to the developers. Thus, evincing an intent to relinquish its access rights, Malloch Construction, on behalf of Bruce LLC, wrote to the Zoning Board in May 2006 requesting a modification of its Powhattan Estates subdivision plan that would leave only a utility easement over the Frain and Palm properties. The letter represented that access to the Cabral lot was from Staples Street, not the Powhattan Estates subdivision. The modification request was granted, and subsequent plans for the Cabral property show only a utility easement over the Frain and Palm properties, with no mention of access.

By June 2006, when Bruce Development applied for a variance to build a single-family home on 335 Staples Street, it had secured an access easement over the adjacent 325 Staples Street property. Although no formal easement agreement was placed on record until September 2006, 325 Staples Street was owned by the Salvo Land Trust, whose principal, Joseph Salvo, also controlled Bruce Development. Thus, an eventual written easement over 325 Staples Street was never in doubt, and it was no longer necessary for Bruce Development to maintain a right to pass and repass over the Frain/Palm easement for access to the Cabral lot. After Malloch Construction installed the underground utilities in the easement, it placed the boulders across the width of the easement and loamed and seeded the easements surface. These boulders run across nearly the entire 20 width of the easement, impeding access either by vehicle or by foot.

All this demonstrates the intent to abandon the right to pass and repass over the Frain/Palm easement. See Lasell College, 32 Mass. App. Ct. at 391 (construction of a fence blocking access to easement along with construction of new roads providing access established abandonment). Unlike Desotell v. Szczygiel, 338 Mass. 153 , 159 (1958), where the Court found no abandonment because an easement was obstructed by its natural cover of trees and brush, here the easement was blocked by deliberate actions that were inconsistent with a general right to pass and repass over the easement for access purposes.

In their post-trial brief, the Cabrals argue that the boulders cannot signify an intent to abandon access rights since it was acknowledged at trial that the boulders could be moved by a backhoe or other construction vehicle. See Plaintiffs Post Trial Memorandum at 16. An obstruction, however, need not be permanent, see Lasell College (a fence), and, despite the Cabrals characterization in their brief that the boulders could be moved relatively easily, the testimony established this could not be accomplished without the aid of a construction vehicle such as a bobcat or excavator.

The Cabrals next contend that Mallochs placement of the boulders cannot be attributed to Bruce Development Corp. or signify Bruces intent to abandon its access rights over the Frain/Palm easement. I disagree. An agency relationship is created when there is mutual consent, express or implied, that the agent is to act on behalf of and for the benefit of the principal, and subject to the principals control. Theos & Sons, Inc. v. Mack Trucks, Inc., 431 Mass. 736 , 742 (2000). Actual authority results when the principal consents, through words or conduct that the agent should act on behalf of the principal. Id. citing Commonwealth Aluminum Corp. v. Baldwin Corp., 980 F. Supp. 598, 611 (D. Mass. 1997).

Malloch Construction has worked with the Bruce entities on various real estate developments for over 20 years. Mr. Mallochs undisputed testimony at trial was that Bruce Development Corp. acts as an investor, supplying the land and the financing while Malloch Construction handles all of the development, the actual work going on

. Bruce Development only created Bruce LLC for the purposes of obtaining a G.L. c. 40B comprehensive permit to develop Powhattan Estates. The managers of Bruce LLC granted Mr. Malloch the power to do all

acts necessary, pertaining to the sale of real estate in the subdivision and to bind Bruce LLC. See Certificate of Authority. Pursuant to that power, Mr. Malloch negotiated the Frain/Palm easement for the benefit of 335 Staples Street, then owned by Bruce Development. Mr. Malloch signed the purchase and sale agreement for the Cabral home on behalf of Bruce Development, noting next to his signature, Cert. of A., indicating that he also had the authority to act on behalf of Bruce Development. For all these reasons, I find and conclude that Malloch Construction acted as the Bruce entities agent in connection with the development and sale of this Bruce-owned real estate, with those entities full knowledge and assent. Mallochs communications with the Zoning Board and its placement of boulders within the easement are therefore binding on Bruce Development.

Remedies

Having concluded that the right to pass and repass over the Frain/Palm easement for access to the Cabral lot was abandoned by the Cabrals predecessor, what remains is a utility easement and the corresponding limited right to access the easement for the purpose of maintaining those underground utilities. The Cabrals contend that this right requires that the entire easement be free from all obstructions through its entire length and width. When the parties submitted their post trial briefs, the SJC had not yet issued its decision in Martin v.

Simmons Properties, LLC, 467 Mass. 1 (2014). That case has now been decided, with the Court adopting a policy of maximiz[ing] the value of property to the owner of a servient estate while protecting the rights of an easement holder. See Martin, 467 Mass. at 10. Thus [a] person who holds the land burdened by a servitude is entitled to make all uses of the land that are not prohibited by the servitude and that do not interfere unreasonably with the uses authorized by the easement

. Id. at 14.

The parties each presented an expert witness who testified about whether the objects in the easement are likely to interfere with the Cabrals ability to maintain their utilities. The Cabrals offered the testimony of Jeffrey Youngquist, a professional land surveyor with experience in designing subdivision plans and utility easements. Mr. Youngquist testified, based on his experience with other subdivision developments, that in the event a utility line needed to be replaced, a construction vehicle, such as a backhoe, would be needed to dig down approximately five feet and a trench box at least five feet long by five feet wide would have to be installed to prevent the sides of the trench from caving in. Emergency access might be needed from time to time, making it important that surface objects be capable of easy removal. Here, the fence down the center of the easement could be easily removed if need be (it is vinyl, with widely-spaced posts). Large trees, bushes, and the boulders, however, are significant obstacles. With respect to the boulders, Mr. Youngquist could not say precisely how much each weighed, [Note 8] but acknowledged that they were very large and could only be moved by some kind of construction vehicle, such as a Bobcat or excavator.

The Frains and Palms offered the testimony of their expert, James Borrevach, a professional engineer who has several years of experience installing utilities in residential and commercial developments. He testified that sections of the fence could be easily manually removed using an electric screwdriver to unscrew the brackets connecting each 8 foot section of fence to the fence posts in the easement. However, he acknowledged that the large trees within the easement are located either too close to the utility lines or have the potential to interfere with those utilities as they grow larger. These include a pine tree, two maples, a poplar and a willow tree. See Ex. 2 [Note 9] (identifying the trees). According to Mr. Borrevach, these trees should be removed as a preventative measure since, unlike the fence, they cannot be easily and quickly removed in the event of an emergency with the underground utilities. Mr. Borrevach testified that other shrubs and an ornamental pear tree on the Palm side of the fence do not need to be removed because, in his opinion, these objects do not grow very large and can be easily dug up if needed. [Note 10]

Since the testimony of both experts established that the fence running down the center of the easement does not presently interfere with the underground utilities, and can be quickly removed if needed for maintenance or repair, I find and conclude that the fence may remain in the easement, consistent with the right of the servient owners to make all beneficial uses of their land that do not unreasonably interfere with the purpose of the easement. [Note 11] See Martin, 467 Mass. at 14. However, the trees shown on Exhibit 2 (attached) with the notation remove, which cannot be easily removed when emergency or other access is needed to the underground utility lines and have the potential to interfere with these utilities, must be removed by the defendants as soon as practicable. Similarly, I find and conclude that the three, large boulders currently in the easement must be removed. They block access to the utility lines in the western half of the easement, and again, unlike the fencing, cannot be removed without a construction vehicle, which may or may not be available in an emergency situation.

In connection with the defendants counterclaim for trespass against the Cabrals, they request that the Cabrals be prohibited from entering onto the portions of their properties burdened by the easement except when accompanied by agents of qualified utility companies. This request is DENIED. As the holders of a utility easement, the Cabrals have the right to go upon the servient land to do acts reasonably necessary for a proper use and enjoyment of the easement. Mt. Holyoke Realty Corp. v. Holyoke Realty Corp., 292 Mass. 332 , 336 (1935). The defendants request that they be awarded fees for the Cabrals alleged trespass is also DENIED. No evidence of damages was presented at trial, and furthermore, I find the Cabrals claims were not insubstantial, frivolous or made in bad faith.

Conclusion

For the foregoing reasons, I conclude that the Cabrals have a 20wide utility easement across the Frain/Palm parcels as shown on Exhibit 1, but do not have a general right to pass and repass across that easement to their lot. The general right to pass and repass has been abandoned. The fences within the easement area may remain, but may be removed by the Cabrals whenever needed for utility installation, maintenance, or repair. The boulders and trees shown on Ex. 2 must be removed at the defendants expense as soon as practicable.

Judgment shall enter accordingly.

CHRISTOPHER CABRAL and CHERYL CABRAL v. SETH FRAIN, COLLEEN FRAIN, STEVEN PALM and KERRY PALM.

CHRISTOPHER CABRAL and CHERYL CABRAL v. SETH FRAIN, COLLEEN FRAIN, STEVEN PALM and KERRY PALM.