Michael and Jane Jackson, trustees of the Jackpot Trust, own a parcel by Chapoquoit Harbor in Falmouth that was once a tidal pond that was filled in the 1920s. Nancy Evans, trustee of the NWW-2 Realty Trust, owns an upland lot that abuts the Jackpot Trust property. Evans claims that she has title to the filled flats of the pond abutting her property that are currently being used and occupied as part of the Jackpot Trusts property because title to those flats was conveyed along with her property by virtue of the Colonial Ordinance of 1641-1647. After trial, I find that these flats were separated from the upland of the Evans property, so that the Jackpot Trust has title to the flats, and that, in addition, the Jackpot Trust has obtained title to this disputed area by adverse possession.

Procedural History

The plaintiff, Nancy Evans, Trustee of the NWW-2 Realty Trust (Evans), filed her verified complaint in this case on July 22, 2013. Evans complaint seeks a Declaratory Judgment that she owns approximately 5,300 square feet of land (Disputed Area) on which the defendants, Michael Jackson, Jr. and Jane Jackson (the Jacksons) as trustees of the Jackpot Trust, plan to construct an addition to their single-family home. On November 4, 2013, the Jackpot Trust filed Defendants Answer to Plaintiffs Complaint and Counterclaim. A case management conference was held on November 21, 2013, where the Court ordered Evans to give the Commonwealth of Massachusetts (Commonwealth) notice of this action. On December 26, 2013, the Reply of Nancy Evans, Trustee, to Counterclaim of Jackpot Trust was filed. A second case management conference was held on January 8, 2014, when the Commonwealth informed the court that it took no position on the proceedings and wished not to be a party in this matter. On February 27, 2015, the Jackpot Trust filed Motion by Defendants to Approve Stipulation by them and the Commonwealth but not Plaintiff or, in the Alternative, to Sever Trial of the Rights of Commonwealth Pursuant to Mass. R. Civ. P. 42(b). On March 2, 2015, the Commonwealth filed an Assent to Defendants Motion to Approve Stipulation or Sever the Trial under Mass. R. Civ. P. 42(b). On March 17, 2014, Evans filed Plaintiffs Opposition to Defendant Jackpot Trusts Motion to Approve Stipulation or Sever Trial. On March 24, 2015, a hearing was held on Defendants Motion in which the Court ruled that [t]he Commonwealth is not a party to this matter and will not be required to appear. This case will not adjudicate the rights of the Commonwealth.

A view of the subject property was taken on June 8, 2015. A trial was held on June 9 and June 10, 2015. Testimony was heard from Bernard Kilroy, Joel Kubick, Katharine King, Caroline Abdulrazak, Thomas Bunker, Timothy Jackson, Robert Moriarty, Jr., Michael Jackson, Jr., and Seth Andrews. Exhibits 1-79 were marked. On the first day of trial, the Jackpot Trust filed Defendants Motion for a Directed Verdict and Defendants Memorandum of Law Relative to Doctrine of Color of Title. The Motion for a Directed Verdict was heard and the Court denied the motion without prejudice. On the second day of trial, Evans filed Plaintiffs Motion for Finding and Judgment on Issues of Adverse Possession, the motion was heard, and the Court denied the motion without prejudice. On August 7, 2015, the Jackpot Trust submitted their Proposed Findings of Fact, Rulings of Law, and a Post-Trial Memorandum of Law. On August 11, 2015, Evans filed the Plaintiffs Post-Trial Memorandum of Law on Claim of Title and a Post-Trial Memorandum of Law on Defendants Counterclaim for Adverse Possession. Closing arguments were heard on September 3, 2015, and this case was taken under advisement.

For the reasons set forth below, I find that the Jackpot Trust is the record owner of the Disputed Area and alternatively, the Jackpot Trust has acquired title of the Disputed Area by adverse possession.

Findings of Fact

Based on the facts stipulated by the parties, the documentary and testimonial evidence at trial, and my assessment as the trier of fact of the credibility, I make factual findings as follows:

Facts Common to Title of Evans and the Jackpot Trust

1. Chapoquoit Island is a peninsula in Falmouth with Buzzards Bay to the west and West Falmouth Harbor wrapping around it to the north, east, and south. Chapoquoit consists of approximately 40 lots along Associates Avenue. Exh. 7; view.

2. Both Evans and the Jacksons can trace their titles back to deeds recorded in the Barnstable County Registry of Deeds (registry) on December 10, 1872 at Book 113, Page 182-183, in which Daniel and Joshua Bowerman (Bowermans) conveyed a one-third interest a 36-acre parcel on Chapoquoit Island, then called Hog Island, to Nathaniel Coleman (Coleman), and two-thirds interest in the same parcel to Franklin King (King). Exh. 1, ¶ 1; Exhs. 2-3.

3. On June 29, 1889, Coleman conveyed his one-third interest in the 36-acre parcel known as Chapoquoit to Charles Jones (Jones) by a deed recorded on July 9, 1889 in the registry at Book 181, Page 353, and by confirmatory deed recorded on September 3, 1890 in the registry at Book 188, Page 331. Exh. 1, ¶¶ 2-3; Exhs. 4-5.

4. As a result of the deeds from the Bowermans and Coleman, Jones was the owner of a one-third interest in Chapoquoit, and King was the owner of a two-thirds interest in Chapoquoit. King and Jones acquired this land with an intention to subdivide it and develop it for the sale of residential lots. Exh. 1, ¶ 4.

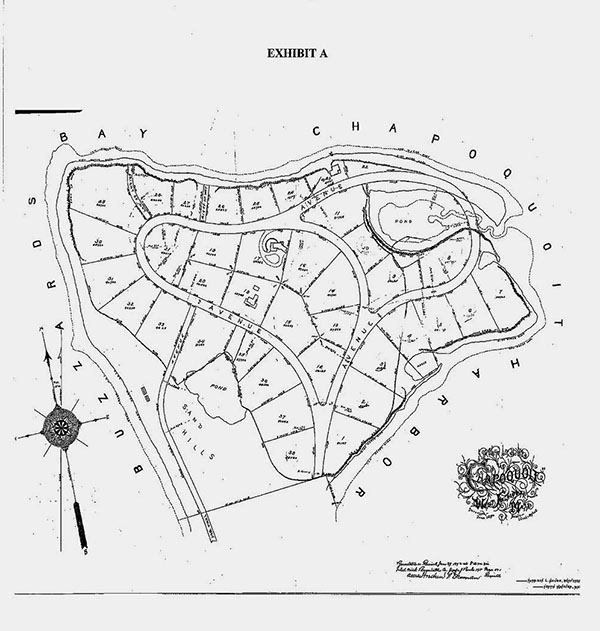

5. In 1890, a plan was created showing 38 subdivided lots (numbered Lots 1-38) surveyed in 1890 and recorded in the registry on January 29, 1892 now indexed at Plan Book 25, Page 24 (1890 Plan), attached here as Exhibit A. The 1890 Plan shows Buzzards Bay, Chapoquoit Harbor, and two ponds, the larger of which to the northeast is at issue in this case (the Pond). The high-water mark and low-water mark that surround Chapoquoit Island are depicted on the 1890 Plan and follow a curve into and around the Pond, in front of the lots abutting the Pond. Exh. 1, ¶¶ 6-7; Exh. 7.

6. King and Jones entered into an agreement dated October 20, 1891 (1891 Agreement) and recorded in the registry on January 11, 1892 at Book 199, Page 187. King and Jones describe themselves as proprietors in equal shares of Chapoquoit and agree to the imposition of certain restrictions to run with the land as shown on the 1890 Plan. The first provision contains the following language:

First: That for the free and convenient use of the shore of said Island by all persons in common who shall become the owners of any of the lots shown on said plan, that portion of land and shore, which lies between the line designated on said plan as Edge of the Bank and the line of low-water mark shall be and remain open and subject to the use of each owner of one of said lots, for him and his family, to pass and repass in common with others entitled, and for such other use as shall not affect or impair the use of any of said lots for quiet, convenient and comfortable dwelling houses; and provided that the grant of such right of way shall not prevent or interfere with the erection and maintenance by said proprietors, for bathing houses, wharves, or such other improvements we shall decide upon, nor impose on us or our heirs or assigns any duty to construct or maintain said way, or any liability arising from the use thereof by any person. (Emphasis added).

Simply put, the 1891 Agreement states that the land between the edge of the bank and the low-water mark is open to any lot owner within the Chapoquoit subdivision, subject to the rights of the proprietors, King and Jones, to construct wharves, boathouses, and things of that nature. Exh. 1, ¶ 5; Exh. 6.

7. On October 5, 1892, King conveyed to Jones his interest in Lot 11 as shown on the 1890 Plan by a deed recorded in the registry on October 20, 1892 at Book 202, Page 529. Exh. 1, ¶ 8; Exh. 8.

8. In September 1893, King and Jones decided to divide the rest of the buildable lots between each other, mutually exchanging their partial interests so that each could become the sole owner in a number of lots. Jones conveyed to King all his shares and interest in Lots 1, 12, 13, 15, 19, 20, and 30-37, as shown on the 1890 Plan by a deed dated September 29, 1893 and recorded in the registry on November 23, 1893 at Book 209, Page 138. King conveyed to Jones all his shares and interests in Lots 2-10, 14, 16, 24, and 38 by a deed dated September 29, 1893 and recorded in the registry on November 23, 1893 at Book 209, 146. The two 1893 deeds are referred to as the Division Deeds. Exh. 1, ¶¶ 9-10; Exhs. 9, 11.

9. Through the mutual conveyances, Jones acquired title to a series of lots that start on the south of Chapoquoit Harbor up around and abutting the Pond, including Lots 8, 9, 10, and 11. Exh. 1, ¶ 10; Exh. 7.

10. The 1893 Division Deeds contain several agreements and the following language:

It is understood however that the shore lots next to Buzzards Bay and Chapoquoit Harbor extend to low-water mark of said Bay and Harbor although their sidelines on said plan are drawn only to the edge of the bank.

Exh. 1, ¶ 11; Exhs. 9, 11.

11. The same day the Division Deeds were executed, Jones conveyed to King his interest in the westerly portion of Lot 22 by a deed dated September 29, 1893 and recorded in the registry on November 23, 1893 at Book 209, Page 140. Exh. 10

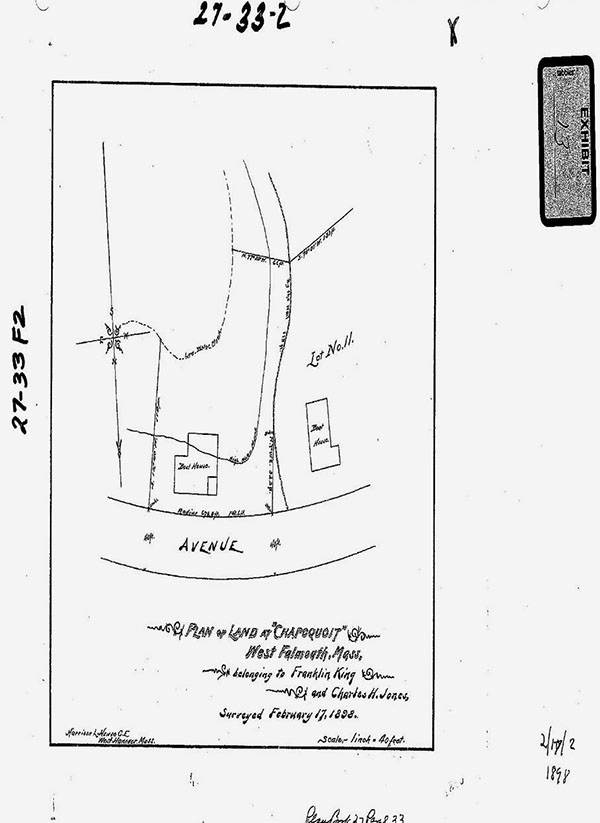

12. On February 17, 1898, another plan of the land at Chapoquoit was prepared and recorded in the registry at Plan Book 27, Page 33 (1898 Plan), attached here as Exhibit B. The 1898 Plan shows an unnumbered lot adjacent to Lot 11, with the boundary line extending to the low-water mark of the Pond. Exh. 1, ¶¶ 16, 20; Exh. 13.

13. King died in 1898. Exh. 1, ¶ 12.

14. On January 2 1899, Jones and the trustees of the estate of King conveyed to John Lathrop Wakefield (Wakefield) all their right, title and interest in the easterly portion of Lot 22 on both sides of the Avenue as shown on the 1890 Plan by a deed recorded in the registry on March 22, 1899 at Book 236, Page 266. The bounds of this portion of Lot 22 are described as Northerly and Easterly by Chapoquoit Harbor; Southerly by said Chapoquoit Harbor, and by a pond. This conveyance was part of a larger conveyance of some of the flats at Chapoquoit along Buzzards Bay and Chapoquoit Harbor. This property was immediately re-conveyed to Jones, Samuel King, and Charles Baker, as trustees of

1.

Chapoquoit Associates, by a deed recorded in the registry on March 22, 1899 in Book 236, Page 270. Wakefield appears to have been a straw. Exh. 1, ¶ 21; Exhs. 16-17.

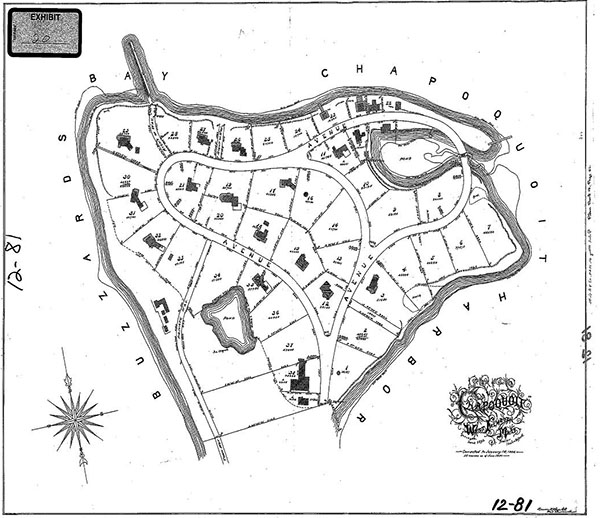

15. A new plan of Chapoquoit January 1, 1904, showing Buzzards Bay, Chapoquoit Harbor, and the Pond, was recorded in the registry in Plan Book 12, Page 81 (1904 Plan), attached here as Exhibit C. The 1904 Plan shows Lots 8, 9, 10, and 11 (further subdivided into Lots 11A and 11B), around the Pond with boundary lines stopping at the edge of the bank. As in the 1898 Plan, the unnumbered lot next to Lot 11B contains a boundary line extending to the low-water mark. Exh. 1, ¶ 24; Exh. 20.

Evans Title

16. Evans, as trustee of the NWW-2 Realty Trust, is the present owner of a developed, residential lot on Chapoquoit, known as Lot 9 with the street number 131 Associates Road. Lot 9 is improved with a three-bedroom house, originally used as a playhouse and a guest house, a single car garage, and a shed. Exh. 1, ¶¶ 49-50, 55; view.

17. On the 1890 Plan, Lot 9 is shown as bounded by an Avenue to the south and adjacent to the Pond to the north, with a feature designated as edge of bank, which serves as the northerly boundary. Exh. 7.

18. On October 31, 1898, Jones conveyed Lot 9 to Samuel King, heir of King, by a deed recorded in the registry on November 3, 1898 at Book 234, Page 230 (1898 Deed). The 1898 Deed recites the propertys metes and bounds, including that it is bounded northwesterly by Lot 10 on the 1890 Plan, one hundred and forty-nine (149) feet, northerly by the edge of the bank as shown on the 1890 Plan, and easterly by Lot 8 by one hundred and fifty four 5/10 (154.5) feet. Overall Lot 9 contains approximately 43,125 square feet. The 1898 Deed also states that it is subject to and with the benefit of all the rights, easements, restrictions and provisions in [the 1893 Division Deeds] contained or referred to so far as the same are now in force and applicable. Exh. 1, ¶¶ 13-15; Exh. 12.

19. On January 2, 1899, trustees of King conveyed to Jones the undivided two-thirds interest of King in the unnumbered lot with the buildings located thereon, shown on the 1898 Plan by a deed recorded in the registry on March 23, 1899 at Book 234, Page 384. The deed to the unnumbered lot refers to the 1898 Plan and recites that the plan is to be recorded herewith. The deed describes the unnumbered lot as bounded by the Pond. Exh. 1, ¶¶ 17- 19; Exhs. 13-14.

20. On May 12, 1899, Jones conveyed the westerly part of Lot 11 (later shown as Lot 11A on the 1904 Plan) to Esther Hitchcock by a deed recorded in the registry on June 3, 1899 at Book 234, Page 488. Exh. 15.

21. On June 1, 1901, Samuel King conveyed Lot 9 to John Hitchcock (Hitchcock) by a deed recorded in the registry on June 3, 1901 at Book 250, Page 113 (1901 Deed). The boundaries and descriptions of Lot 9 in the 1901 Deed are identical to those in the 1898 Deed, including that Lot 9 is bound northerly by the edge of bank as shown on [the 1890 Plan]. Exh. 1, ¶ 22; Exh. 18.

22. On June 1, 1901, Jones conveyed Lot 10 as shown on the 1890 Plan to Hitchcock by a deed recorded in the registry on June 26, 1901 at Book 250, Page 147. Exh. 1, ¶ 23; Exh. 19.

23. On March 20, 1912, executors of the estate of Hitchcock conveyed Lots 9 and 10 to Theodore E. Stephenson (Stephenson) by a deed recorded in the registry on March 27, 1912 at Book 314, Page 425. The same day, Stephenson conveyed Lots 9 and 10 to Esther Hitchcock, individually, by a deed recorded in the registry March 27, 1912 at Book 313, Page 184. For the description of Lot 9, these deeds refer to the 1901 Deed. By virtue of this conveyance and the 1899 conveyance described above, Esther Hitchcock was the owner of Lots 9, 10, and 11A as shown on the 1904 Plan. Exh. 1, ¶¶ 25-26; Exhs. 15, 21-22.

24. On May 20, 1924, Jones conveyed Lot 11B as shown on the 1904 Plan to Nancy and George Crompton (Cromptons) by a deed recorded on May 31, 1924 in the registry at Book 402, Page 463. Exh. 1, ¶ 27; Exh. 23.

25. On October 14, 1929, Esther Hitchcock conveyed Lots 9, 10, and 11A to Mabel A. Heald (Heald) by a deed recorded in the registry on October 21, 1929 at Book 467, Page 588. The boundaries and description of Lot 9 in this deed are identical to those in the 1898 Deed, as well as in the 1901 Deed, including that Lot 9 is bound northerly by the edge of the bank as shown on [the 1890 Plan]. Exh. 1, ¶ 30; Exh. 24.

26. On November 3, 1930 Heald conveyed Lots 9 and 10 to the Cromptons by a deed recorded in the registry on November 7, 1930 at Book 475, Page 263. The boundaries and descriptions of Lot 9 in this deed are identical to those in Lot 9s chain of title, including that Lot 9 is bound northerly by the edge of bank as shown on [the 1890 Plan]. Exh. 1, ¶ 31; Exh. 25.

27. On November 4, 1943, George Crompton conveyed Lots 9, 10, and 11B to Nancy Jenney, formerly Nancy Crompton, individually by a deed recorded in the registry on March 6, 1944 at Book 611, Page 266. The boundaries and descriptions of Lot 9 in this deed are identical to those in the 1898 Deed and 1901 Deed, including that Lot 9 is bounded northerly by the edge of bank as shown on [the 1890 Plan]. Exh. 1, ¶ 38; Exh. 31.

28. On July 25, 1950, Paul Jones conveyed to Nancy Jenney by a deed recorded in the registry on July 31, 1950 at Book 758, Page 588, a portion of the unnumbered lot (Jenney parcel) shown on the 1898 Plan and 1904 Plan as abutting Lot 11B to the east. The Jenney parcel can be seen on the 1958 Plan (discussed later), attached here as Exhibit E. Exh. 1,

¶ 39; Exhs. 32-33.

29. On December 20, 1968, Nancy Jenney conveyed Lots 9, 10, and 11B, and the Jenney parcel to her daughter Nancy Willard Wendell (Wendell) by a deed recorded in the registry on December 26, 1968 at Book 1423, Page 454. The boundaries and descriptions of Lot 9 in this deed are identical to those in the Lot 9s chain-of-title, including that Lot 9 is bound northerly by the edge of bank as shown on [the 1890 Plan]. Exh. 1, ¶ 45; Exh. 35.

30. On November 28, 1994, Wendell conveyed Lots 10 and 11B and the Jenney parcel to herself, as trustee of the NWW-1 Realty Trust, by a deed recorded in the registry on December 5, 1994 at Book 9469, Page 109. Lot 11B and the Jenney parcel together now have the address of 73 Associates Road and are improved with a single-family dwelling used as the Wendell familys main house. Lot 10 is an undeveloped wooded lot known as the Middle Lot. Exh. 1, ¶¶ 47-48; Exh. 37; Tr. 1:112; view.

31. On November 28, 1994, Wendell also conveyed Lot 9 to herself, as trustee of the NWW-2 Realty Trust by a deed recorded in the registry on December 5, 1994 at Book 9469, Page 118. The boundaries and descriptions of Lot 9 in this deed are identical to those in the chain-of-title, including that Lot 9 is bound northerly by the edge of bank as shown on [the 1890 Plan]. Lot 9 now has an address of 131 Associates Road and is improved by a three- bedroom residence, originally used as a playhouse and guesthouse after it was constructed in the 1920s or 1930s. The residential structure continues to be known as the Playhouse. Exh. 1, ¶¶ 49-50; Exh. 38; Tr. 1:112-113; view.

32. Wendell died on November 30, 2004. She was survived by three daughters: Nancy Evans (the plaintiff), Gwendolyn Bryant, and Caroline Abdulrazak. Wendells daughters became trustees of the NWW-1 and NWW-2 Realty Trusts. A plan was prepared for division of ownership among the three daughters of Lots 9, 10, and 11B and the Jenney parcel entitled Existing Conditions Plan for Cally Abdulrazak dated January 6, 2006. Real estate appraisals of the properties were obtained. The size or area of each of the three lots and the Jenney parcel was a major component of the appraisals. Evans did not communicate any disagreement with the division plans depiction of the property line along the Jacksons property. Tr. 1:117; Exh. 1, ¶¶ 51-54.

33. On or about October 29, 2011, Evans became the sole trustee of NWW-2 Realty Trust, which holds title to Lot 9 (the Evans Property). Evans and her two sisters became trustees and beneficiaries of NWW-1 Realty Trust for Lot 10. Evans sisters became the trustees and beneficiaries of NWW-1 Realty Trust for Lot 11B and the Jenney parcel. Evans and her three daughters are the current beneficiaries of the NWW-2 Realty Trust. Exh. 1, ¶ 55.

34. After becoming the sole trustee of NWW-2 Realty, Evans asserted that title to Lot 9 included the Disputed Area, filled tidelines of the prior Pond (discussed below). Evans relies on the language in the 1893 Division Deeds describing the boundary of the shore lots as being extended to low-water mark of the Bay and Harbor, and on the 1898 Deed of Lot 9 from Jones to King that was subject to and with the benefit of all the rights, easements, and restrictions in the 1893 Division Deeds. Tr. 1:26-29.

35. Evans admits that prior to filing this action she did not believe the Disputed Area was part of her property. Exh. 1, ¶ 57.

Jackpot Trusts Title

36. On April 1, 1926, Jones conveyed an unnumbered lot (Jones parcel) to his heir Paul Jones by a deed recorded in the registry on May 2, 1931 at Book 481, Page 293 (1931 Deed). The Jones parcel abuts the Jenney parcel to the east, as shown on the 1904 Plan and 1958 Plan (discussed below). The boundary line of the Jones parcel was extended from the low-water mark across the Pond to the edge of the bank on the Northerly side of Lot 9, then running northwesterly along the edge of the bank to the southeasterly side line of Lot 10, forming the northeasterly boundary of Lot 10, then to the southeasterly corner of Lot 11B, forming the easterly boundary of Lot 11B, and up to the southerly boundary of the Avenue, as shown on the 1890 Plan. Exh. 1, ¶ 33; Exh. 26.

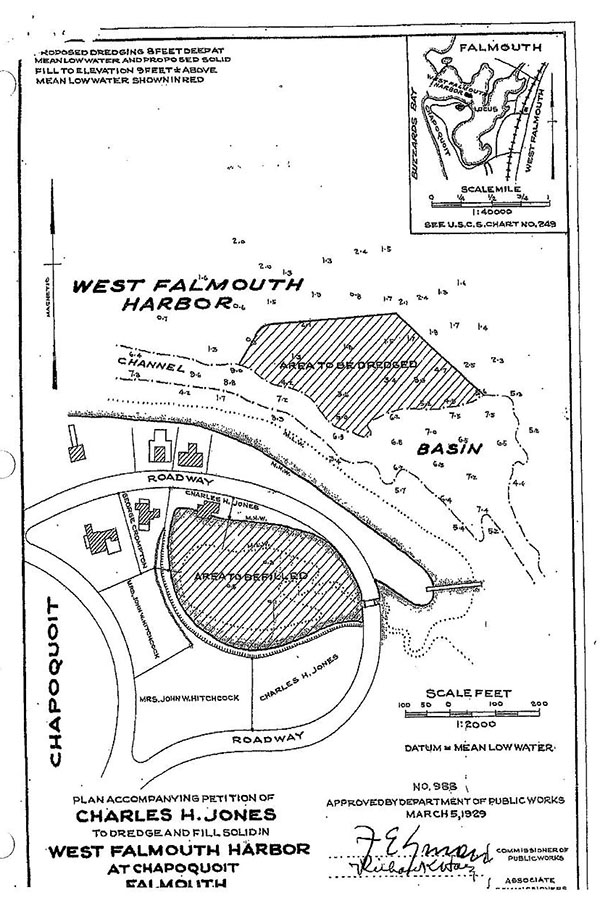

37. On or about March 7, 1929, the Department of Public Works of the Commonwealth issued a Chapter 91 license to Jones authorizing dredging in West Falmouth Harbor and placement of the dredged materials in tidewater in a pond tributary to said harbor, at Chapoquoit. No evidence was found that the license was recorded in the registry. At some point during the late 1920s or early 1930s, the dredging and filling of the area shown on a 1929 license plan (1929 Plan) occurred. The 1929 Plan is attached here as Exhibit D. Exh. 1, ¶¶ 28-29, 32; Exhs. 44-45.

38. Jones died on January 4, 1933. Exh. 1, ¶ 34.

39. On December 19, 1933, the trustees of King executed a use deed to Willard Morse, recorded in the registry on January 23, 1934 at Book 501, Page 63, conveying all of their right, title and interest, if any, in and to any land or interest in land in the town of Falmouth, Barnstable County, Massachusetts, including any flats or easements to the use of Willard Morse and his heirs as described in the deed; i.e. Franklin King, Margaret Farnsworth, Gelston King (an undivided half interest as tenants in common), and Anna Hall and Edith Baldwin (an undivided half interest as tenants in common). Exh. 1, ¶ 35; Exh. 27.

40. The same day, the trustees of King granted to the trustees of Jones all of their right, title and interest, if any, in the land under or included within the limits of the Pond adjacent to Lots 8, 9 and 10 and in any flats and lands lying between low-water mark of said Pond as shown in the 1890 Plan and 1904 Plan, by a deed recorded in the registry at Book 501, Page 63. These two deeds executed on January 23, 1934, are referred to as the 1934 Deeds. Exh. 1, ¶ 36; Exh. 28.

41. On July 10, 1934, trustees of Chapoquoit Associates conveyed the easterly portion of Lot 22, the portion conveyed by the January 2, 1899 deed, to the trustees of Jones by a deed recorded in the registry on July 26, 1934 at Book 504, Page 186. Exh. 29.

42. On February 7, 1935, the trustees of Jones conveyed to Paul Jones Lot 8 and the land under or included within the limits of the pond adjacent to Lots 8, 9 and 10 as shown on [the 1904 Plan], all flats or land lying between said Lots 8, 9, and 10, and low-water mark of said pond as shown on [the 1904 Plan] and a portion of Lot 22 . . . lying to the southwesterly side of said Associates Road by a deed recorded in the registry on February 9, 1935 at Book 508, Page 537 (1935 Deed). Exh. 1, ¶ 37; Exh. 30; Tr. 2:23-24.

43. At some point in the late 1950s, a single-family residence was built by Paul Jones, the Jacksons predecessor-in-interest, on a portion of the filled former Pond lying to the northeast of Lot 10 and north of Lot 9. Tr. 2:41; Exh. 1, ¶ 40.

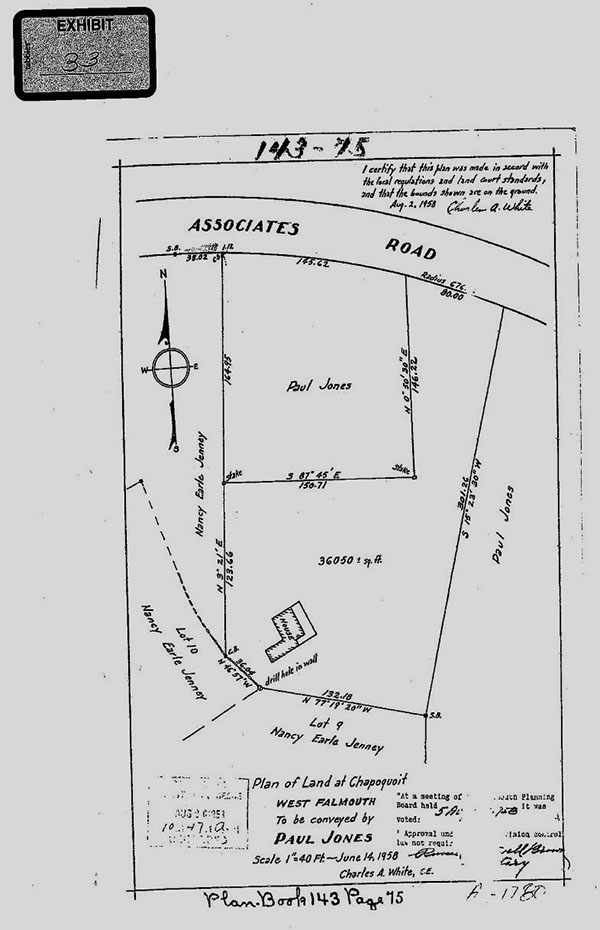

44. On or about August 5, 1958, the Falmouth Planning Board endorsed as approval not required under the Subdivision Control Law a plan entitled: Plan of Land at Chapoquoit West Falmouth to be conveyed by Paul Jones June 14, 1958 (1958 Plan), attached here as Exhibit E. The 1958 Plan was recorded at the registry at Plan Book 143, Page 75. The 1958 Plan shows the location of the residence built by Paul Jones marked house in its current location on a 36,050 square foot parcel of land (the Jackson Property). The house, commonly referred to as the Jackpot, is a two-story, four bedroom structure. Thereafter, a detached single car garage was built to the north of the Jackpot. Tr. 2:42; Exh. 1, ¶¶ 41-43; Exh. 33; view.

45. On August 25, 1958, Paul Jones conveyed to his niece and her husband, Michael Jackson, Sr. and Leslie Jones Jackson, a 36,060 sq ft parcel of land, now known as the Jackson Property, by a deed recorded in the registry on August 26, 1958 at Book 1013, Page 271 (1958 Deed). The 1958 Deed describes the Jackson Property by metes and bounds and as being shown on the 1958 Plan. Exh. 1, ¶ 44; Exh. 34.

46. On December 21, 1976, Michael Jackson, Sr. and Leslie Jones Jackson conveyed the Jackson Property to the Fiduciary Trust Company, as trustee of the Jackpot Trust, by a deed recorded in the registry on December 27, 1976 at Book 2446, Page 306. Exh. 1, ¶ 46; Exh. 36.

47. On or about November 1, 2013, the Jacksons became the sole trustees of the Jackpot Trust, which is the present owner of the Jackson Property with the street address 85 Associates Road. Tr. 2:42, 64; Exh. 1, ¶ 56.

48. The Jackson Property is on a portion of the Pond that was filled and abuts the now Evans Property. The Disputed Area is southeast and east of the Jackpot, and to the northeast of the Playhouse on the Evans Property. Exh. 1, ¶ 28; Exhs. 33, 55, 59, 60; view.

Title to the Disputed Area

49. At trial, ownership of the Disputed Area was at issue. The dispute centers on whether the Disputed Area was intended to be included in conveyances of Lot 9, or whether the grantors did not intend to convey this additional area along with Lot 9.

50. Evans asserts that her ownership of Lot 9 extends from (what was once) the edge of bank to the low-water mark of the former Pond, i.e. the Disputed Area. The Disputed Area is approximately a 5,300 square foot strip on filled tidelands where the Pond on the 1890 Plan was once located.

51. Bernard Kilroy (Kilroy), a Massachusetts real estate attorney with experience in title examination, and Land Court title examiner since 1971, testified on behalf of Evans. He opined that it was his understanding of the common law that if the tidal flats were owned by the grantor, they are presumed to be conveyed with the conveyance of adjacent upland, and that he discerned no intent to sever the Disputed Area from Lot 9 in the 1898 Deed from Jones to Samuel King. He testified that he detected no intent on the part of Jones and King to convey any of the lots bordering the Chapoquoit Harbor and Buzzards Bay differently than the lots bordering the Pond, with respect to the treatment of the tidal flats.

However, Kilroy did not testify as to whether any of the subsequent deeds in the chain of title, following the 1898 Deed, corroborated his interpretation of the grantors intent. Kilroy failed to offer any explanation for deeds after the 1898 Deed that contradicted his interpretation. He acknowledged on cross-examination that there is nothing in the 1890 Plan that indicates that the Pond should be transferred with Lot 9 and that according to the 1890 Plan, the edge of bank is the northern boundary of Lot 9. Kilroy further conceded that, putting aside the subject to language in the 1898 Deed, there is nothing in the 1898 Deed that shows that the deed conveys any part of the Pond. Tr. 1:19-23, 33-35, 38, 41-42, 58, 60.

52. Robert Moriarty (Moriarty), a Massachusetts real estate attorney with a specialty in title examination, a member of Title Standards Committee of the Real Estate Bar Association since the 1980s, and a Land Court title examiner, testified on behalf of the Jacksons. He opined that when the 1893 Division Deeds used the term shore lots, they were referring specifically to the shore lots abutting Chapoquoit Harbor and Buzzards Bay. He also testified that there were several significant factors to be considered in interpreting the 1898 Deed of Lot 9 from Jones to King. The 1898 Deed references the 1890 Plan, showing Lot 9 not including the Pond, and provides a metes and bounds description. The language for the northerly bound is along the edge of bank, indicating that Lot 9s boundary extended only to the edge of the bank and not beyond. He testified that he reviewed the deeds in Evans chain of title, and that they uniformly describe the northern boundary of her property as bounded by the edge of the bank, just as the initial 1898 Deed described it. Moriarty attested to other deeds for property on Chapoquoit Island in which both King and Jones differentiated between the Harbor, the Bay, and the Pond. He further testified that the 1934 Deeds were release deeds from the estate of King to the estate of Jones for any right, title, or interest they may have had within the limits of the Pond. This was done, Moriarty said, to ensure that the Division Deeds did not leave out any residual interest in the King estate. Moriarty also stated that he checked the authority of those grantors to execute that deed, reviewed probate materials for each estate, and verified that the trustees were the proper trustees. Moreover, Moriarty stated that the license obtained by Jones to fill the entire Pond was an indication that Jones believed he owned the entire Pond area. I credit Moriartys testimony as to the Evans and the Jacksons chain of title. Tr. 2:11-15, 17-22; Exhs. 12, 14, 16, 26-28, 44.

53. Based on the documentary evidence in the record and Moriartys testimony, I find that the Disputed Area was not intended by the original grantors to be transferred as part of Lot 9. I accept and adopt Moriartys view that there was no evidence in the 1898 Deed

description of an intent to convey property to the low-water mark as part of Lot 9; in fact the language in the deed specifically referenced the northern boundary of Lot 9 as the edge of bank. The 1891 Agreement, the Division Deeds, and subsequent deeds to the 1898 Deed all differentiate between the Harbor, the Bay and the Pond. Additionally, several deeds in the Jackpot Trusts chain of title, including the 1931 Deed and 1935 Deed, conveyed the Pond along with the Disputed Area. Tr. 2:11-15, 17-24; Exhs. 12, 14, 16, 26.

Adverse Possession

54. Aerial photographs from the 1950s and 1960s show the Jackpot was placed along the landward edge of a large open area that extended from within about the center of a loop of Associates Road, across Associates Road, to the shore of Chapoquoit Harbor. Several witnesses referred to this open area as the Plains of Abraham. This area was created when the Pond was filled. It was initially maintained as an open area, but in the 1970s was cut less so trees and shrubs grew upon the northern and northeastern portion of the Jackson Property. Tr. 1:119-120, 144, 160-161; 2:57-58, 67; Exhs. 47-53.

55. Defendant Michael Jackson, Jr. (Mr. Jackson) testified that his family acquired the Jackson Property in the late 1950s. When he was growing up, his parents took him and his three siblings to stay at the Jackpot during the summer and occasionally in the spring and fall. I credit Mr. Jacksons testimony. Tr. 2:42-43.

56. While trees or shrubs established themselves over the years in parts of the Plains of Abraham outside the Disputed Area, the lawn area near and around the Jackpot remained substantially the same from the late 1950s to the present. This area was mowed and maintained as lawn by Michael Jackson, Sr., Mr. Jackson, and his brother Timothy Jackson. Tr. 1:96-99, 109, 121, 147; 2:48-56; Exhs. 50-54, 61, 65, 79; view.

57. Consistent with the homeowner associations guidelines, the Jacksons and their predecessors-in-interest maintained a vegetated buffer along what they believed to be the property boundary between their property and the Evans Property. A portion of this boundary consists of a privet hedge that Mr. Jackson testified has been there since his childhood in the 1960s. Since the 1960s or 1970s, the Jacksons and their predecessors have placed brush trimmings from the hedges and other vegetation in piles in the southeast corner of the Disputed Area and along the boundary. Tr. 1:146; Tr. 2:61, 72-75, 84-86; Exh. 61; view.

58. Mr. Jackson testified that every few years his father checked the property boundary markers that indicated the ends of the boundary line that the Jacksons now contend is the correct boundary between the Jackson Property and Evans Property, up to the prior edge of the bank. I credit this testimony. These monuments still exist. A drill hole in a stone wall monument marks the western end of the boundary, and a stone bound indicates the eastern end. Tr. 2:60-61, 80-81; Exh. 33; view.

59. The Jacksons and their predecessors used a portion of the Disputed Area as a laundry yard from at least the early 1960s through the 1980s. A large umbrella-style structure had multiple laundry lines strung from it. It was used to dry laundry, and, after the

mid-2000s, just towels and bathing suits. Tr. 1:95-96, 107-108, 112, 144-46; 2:46-47, 66, 78-

79, 82, 100; Exhs. 72, 79.

60. Since at least the early 1960s until 2013, a hammock was hung in the Disputed Area between two cedar trees, one of which was knocked down by a storm in the winter of 2013. The hammock was put to a full range of uses, from reading and resting to children horsing around, including trying to launch each other into space. Chairs and a picnic table were placed and used near the location of the hammock. Tr. 1:95-96, 120, 145, 147; Tr. 2:48, 82-83, 96, 103; Exhs. 63-64; view.

61. The Disputed Area was also used for the storage of boats and boat trailers since the 1960s, such as Mr. Jacksons fathers various boats including a 26-foot long sailboat. More recently, kayaks as well as Mr. Jacksons uncle Paul Jones Sunfish sailboat have been stored in this area. Mr. Jackson testified that his great uncles Sunfish has been stored there for 15 years, and I credit this testimony. Tr. 1:109-110, 146, 165; Tr. 2:59-60; Exh. 66; view.

62. The Jacksons and their predecessors undertook a number of different family outdoor and recreational activities in the Disputed Area beginning in the late 1950s to the present. Mr. Jackson and his brother testified at trial to spending childhood summers in the late 1950s and 1960s at the property with their family of six playing croquet, Frisbee, Jarts, badminton, kick-the-can, and throwing the ball for the family dog. There were cookouts, and for the adults, cocktail parties. It was their fiefdom. Caroline Abdulrazak (Abdulrazak), sister of Evans, testified to observing the Jackson family beginning in the 1950s using every inch of the property, including the Disputed Area. Abdulrazak recalled playing baseball, capture the flag, and having social events on the Jackson Property. Mr. Jacksons children have continued to play in the Disputed Area. I credit this testimony. Tr. 1:118-120 143-144, 151, 162; Tr. 2:62-63.

63. From 1973 to 1983, Katherine King and her family of five rented the Jackson Property in August and September and undertook similar activities on the Jackson Property and in the Disputed Area. She testified that her family played games such as croquet, kick the can, and tag. She also recalled an umbrella style clothesline and a hammock that used to be in the Disputed Area where they hung laundry and bathing suits. Her family also had cookouts and ate in the Disputed Area. She visited the Jackson Property again recently prior to trial and she noted that the Disputed Area looked much the same today as it did when she rented, though missing a large cedar tree that had once held the hammock. I credit Ms. Kings testimony. Tr. 1:93-99, 101-102; Exh. 61.

64. Mr. Jackson and his brother Timothy Jackson continued to use the Jackpot and Disputed Area as their families expanded. Starting in the 1980s, Mr. Jackson and his family would occupy the Jackpot during July and his brothers family would stay at the Jackpot during August. Mr. Jackson placed and maintained a jungle gym with a swing set in the northeastern part of the Disputed Area for his children to use. The jungle gym was there from the early 1990s through the early or mid-2000s. Tree forts were constructed and used by the children in the southeastern portion of the Disputed Area. The sharing of the Jackpot continued until around 2004, after which Mr. Jacksons family exclusively stayed at the Jackpot year-round as long as the weather is suitable. Tr. 1:143-144, 151, 162; Tr. 2:43-45, 62-63; Exh. 64.

65. The portion of the Evans Property closest to the Disputed Area was, until mid- 2009, densely wooded. The vegetation was described as impenetrable and a dense jungle. The area between the Playhouse and the Disputed Area could not be traversed. In May or June 2009, Evans cleared a sizeable portion of her property and installed a lawn and landscaping. Tr. 1:113; Tr. 2:70-71, 75-77, 87,106-107; Exh. 66; view.

66. Until winter of 2013, there were three cedar trees just off the eastern corner of the Jackpot. The southernmost one in the Disputed Area was knocked down in a winter storm and fell toward the Evans Property. The Jacksons left the fallen tree where it lay for over a year because it restored some of the privacy that Evans clearing had removed. The Jacksons had the tree removed and equipment used tore up the lawn, which the Jacksons replanted. Tr. 2:65-71, 74; Exhs. 62, 66; view.

67. In 2014, survey crews came onto the Disputed Area and cut some of the privet hedge to create a sight line. A replacement privet hedge was installed shortly after and the Jackson planted a new Leyland cypress and mulch in the Disputed Area. Tr. 2:74-75; Exh. 61; view.

68. The Jacksons and their predecessors paid taxes assessed by the Town of Falmouth over the years. The assessors maps show the boundaries and shape of the Jackson Property as more or less the same that is shown on the 1958 Plan. The assessors maps include the Disputed Area as within the Jackson Property, not the Evans Property. Evans made no claim that she paid taxes on the Disputed Area or that taxes on the Disputed Area were assessed to her. Tr. 2:63-64; Exhs. 55-57.

69. Mr. Jackson testified that to his knowledge, the above activities in the Disputed Area were never objected to by Evans or her predecessors. Several witnesses testified on behalf of the Jacksons that they were not aware that Evans or her predecessors had ever told the Jacksons, their predecessors, or any tenants not to use any portion of the Disputed Area or otherwise protest the use of the Disputed Area. I credit this testimony. Evans admits that prior to filing this action she did not believe the Disputed Area was part of her property. Evans presented no testimony on the issue of adverse possession. Tr. 1:102, 120-121; Tr. 2:75, 77, 109; Exh. 1, ¶ 57.

Discussion

Evans seeks a declaratory judgment that she owns the Disputed Area, on which the Jacksons plan to construct an addition to their single-family home, through her chain of title. She claims that her ownership of Lot 9, as shown on the 1890 Plan, extends from what was once the edge of the bank to the low-water mark of the former Pond. Evans admits that while the Disputed Area is not explicitly included in Lot 9s deed descriptions in her chain of title, the Disputed Areas conveyance is presumed because the grantor owned the tidal flats at the time or, alternatively, provisions in the 1893 Division Deeds were understood to also include conveyance of the land to the low-water mark for shore lots, including lots on the Pond, and the 1898 Deeds subject to language, the first deed in her chain of title, conveyed this area. The Jackpot Trust argues that it has record title to the Disputed Area, consisting of the flats of the Pond, because the original grantors did not intend to convey the area between the edge of the bank and the low-water mark with the lots surrounding the Pond. If its claim of record title should fail, the Jackpot Trust asserts in its counterclaim that it nonetheles has acquired title to the Disputed Area through the principles of adverse possession. As explained more thoroughly below, I find that the Jackpot Trust, not Evans, has record title to the Disputed Area and, alternatively, that the Jackpot Trust has adversely possessed the Disputed Area for at least twenty years.

A. Record Title to the Disputed Area

The Colonial Ordinance of 1641-1647 established that a person holding land adjacent to the sea shall hold title to the land out to the low water mark or 100 rods (1,650 feet), whichever is less. Pazolt v. Director of the Div. of Marine Fisheries, 417 Mass. 565 , 570 (1994); see Boston Waterfront Dev. Corp. v. Commonwealth, 378 Mass. 629 , 635-637 (1979), quoting The Book of the General Laws and Liberties 50 (1649); Storer v. Freeman, 6 Mass. 435 , 437 (1810); Kane v. Vanzura, 78 Mass. App. Ct. 749 , 753 (2011). Evans bases her claim to ownership of the Disputed Area on two arguments: first, that under the Colonial Ordinance there is a presumption of law that title to the flats follows title to adjacent upland, and second, that Jones acquired title to the Disputed Area by the 1893 Division Deed that conveyed all interests of King to Jones and that the subject to language in the 1898 Deed of Lot 9 from Jones to Samuel King, Evans predecessor in title, included title to the Disputed Area.

The basic principle governing the interpretation of deeds is that their meaning, derived from the presumed intent of the grantor, is to be ascertained from the words used in the written instrument, construed when necessary in the light of the attendant circumstances. Patterson v. Paul, 448 Mass. 658 , 665 (2007), quoting Sheftel v. Lebel, 44 Mass. App. Ct. 175 , 179 (1998); Town of Stoughton v. Schredni, 7 LCR 61 , 66 (1999) (The general principle governing the interpretation of deeds is that they are to be construed so as to give effect to the intent of the parties.). When a deed description is clear and explicit, there is no room for construction or for the admission of parol evidence to prove that the parties intended something different than what they expressed in writing and recorded in the deed language. Black v. Klaetke, 20 LCR 120 , 122 (2012), citing Cook v. Babcock, 61 Mass. 526 , 528 (1851).

Conversely, if a deed appears to be ambiguous and rules of construction are necessary to interpret a deeds description, consideration of circumstances outside the express language of the deed is necessary, as the description itself is no longer sufficient to show the intent behind the conveyance. Black, 20 LCR at 122, citing Murphy v. Mart Realty of Brockton, Inc., 348 Mass. 675 , 680 (1965) (in considering a rule of construction, the basic question remain[ed] one of ascertaining the intent of the parties as manifested by the written instrument and the attendant circumstances). In situations of doubt or ambiguity, subsequent conduct and later deeds are sometimes helpful in resolving that uncertainty, because property owners' descriptions and actions may be indicative of the originally intended grant, and those of their successors may mirror and follow them. See Jones v. Gingras, 3 Mass. App. Ct. 393 , 398 (1975), citing Fulgenitti v. Cariddi, 292 Mass. 321 , 325 (1935) ("Acts of adjoining owners showing the practical construction placed by them upon conveyances affecting their properties are often of great weight"); see also Ryan v. Stavros, 348 Mass. 251 , 259-260 (1964) (use of extrinsic evidence is helpful in resolving uncertainty created by deed descriptions).

Each party asserts that the rules of deed construction warrant an interpretation that favors them. Rules of deed construction provide a hierarchy of priorities for interpreting descriptions in a deed. Descriptions that refer to monuments control over those that use courses and distances; descriptions that refer to courses and distances control over those that use area; and descriptions by area seldom are a controlling factor. Paull v. Kelly, 62 Mass. App. Ct. 673 , 680 (2004). The only exception recognized is where, by strict adherence to monuments, the construction is plainly inconsistent with the intention of the parties as expressed by all the terms of the grant. Temple v. Benson, 213 Mass. 128 , 132 (1912). A plan referred to in a deed becomes part of the contract so far as may be necessary to aid in the identification of the lots and to determine the rights intended to be conveyed. Reagan v. Brissey, 446 Mass. 452 , 458 (2006), quoting LaBounty v. Vickers, 352 Mass. 337 , 339 (1967).

Evans acknowledges that no language in the 1898 Deed to Lot 9 includes the Disputed Area, but rather first rests her argument on the presumption under the Colonial Ordinance that title to the flats follows title to adjacent uplands. This presumption can be overcome. Kane, 78 Mass. App. Ct. at 756. [A]n owner may separate his upland from his flats, by alienating the one, without the other. Valentine v. Piper, 39 Mass. 85 , 94 (1839); Storer, 6 Mass. at 439 ([T]he owner may sell his upland without the flats, or any part thereof, without the upland.); see Commonwealth v. City of Roxbury, 9 Gray 451 , 524-525 (1857). [Note 1] [T]he owner may convey the upland without the flats, or the flats without the upland. Porter v. Sullivan, 73 Mass. 441 , 445 (1856). The presumption can be rebutted by evidence, such as the specific language in deeds in the chain of title conveying the property that demonstrates the intent of the parties. City of Roxbury, 9 Gray at 525. Which party's chain of title includes the Disputed Area is ascertained, therefore, by studying the 1893 Division Deeds, the 1898 Deed, and the 1890 Plan, with ambiguities resolved by examining extrinsic evidence.

The 1893 Division Deeds each state, in relevant part: It is understood however that the shore lots next to Buzzards Bay and Chapoquoit Harbor extend to low-water mark of said Bay and Harbor although their sidelines on said plan are drawn only to the edge of the bank. Exh. 1, ¶ 11. The 1890 Plan shows four bodies of water: Buzzards Bay, Chapoquoit Harbor, and two ponds. Exh. 1, ¶ 7; Exh. 7. Lot 9 is adjacent to the larger of the two ponds. It is not next to the Bay or the Harbor. I find persuasive Moriartys testimony that the language in the 1893 Division Deeds is not applicable to Lot 9, since Lot 9 is not a shore lot located on the Bay or Harbor.

Tr. 2:10. Other deeds for land on Chapoquoit Island, such as the 1899 deed from King and Jones to John Lathrop Wakefield, make specific reference to the Harbor, Bay, and the Pond, showing that the original grantors recognized a distinction between lots bordering the ponds and those abutting the Bay and Harbor. Exh. 1, ¶ 21; Exhs. 16, 26-28, 35. Though Kilroy testified that he detected no intent on the part of Jones and King to treat any of the lots bordering the Harbor and Bay differently than the lots bordering the Pond with respect to the treatment of the tidal flats, he provided no relevant evidence or surrounding circumstances supporting that conclusion.

The 1898 Deed from Jones to Samuel King describes the land conveyed as that shown as Lot 9 on the 1890 Plan. As conceded by Evans, the 1890 Plan does not include the Disputed Area as part of Lot 9. Both the 1898 Plan and the 1904 Plan show the unnumbered lots boundary as extending to the low-water mark, suggesting that the grantors knew how to convey the tidal flats for certain lots if that was the desired intent. Lot 9s boundaries, however, stop at the edge of the bank, with no lines going down to the low-water mark. The 1898 Deed provides a precise metes and bounds description of the land conveyed, including distances and references to abutting lots. It specifies that Lot 9 is bounded northwesterly by Lot 10 on the 1890 Plan one hundred and forty-nine (149) feet, northerly by the edge of the bank as shown on said plan, and easterly by Lot 8 by one hundred and fifty four 5/10 (154.5) feet. It further states that Lot 9 contains 43,125 square feet. Exh. 1, ¶¶ 13-14; Exhs. 7, 12. Kilroy testified that conveyances by the bank typically indicates that tidal flats are not included and if a grantor intends to convey flats, it is common to say so specifically. Tr. 1:49-51, 60. Moreover, Moriarty testified that conveyancers at this time were well aware of the use of the word edge or line, and deeds stating boundaries to the edge of the bank meant to go to the edge of the bank and not to include anything that went beyond. It was Moriartys opinion that the 1898 Deed contained no such intent to convey the flats. Tr. 2:13. There is no specific language in the 1898 Deed, or any of the subsequent deeds of Lot 9, evidencing a contrary intent. In fact, the specific metes and bounds included in all the deeds in the chain of title to Lot 9 describe the northern boundary as the edge of the bank. Exhs. 18, 21, 22, 24-25, 31, 38. Kilroy did not testify with respect to any of the deeds following the 1898 Deed.

The 1898 Deed also states that it is subject to and with the benefit of all the rights, easements, restrictions and provisions in [the 1893 Division Deeds] contained or referred to so far as the same are now in force and applicable. Exhs. 11-12. As previously stated, I find that the provision in the 1893 Division Deeds regarding shore lots is inapplicable to Lot 9, since Lot 9 is not a shore lot abutting the Bay or Harbor. Additionally, Moriarty stated that the subject to language was a catchall provision that is typical where you have a subdivision that has a set of restrictions and agreements intending to incorporate that. Moriarty did not believe that this provision intended to modify the metes and bounds description of Lot 9. Tr. 2:31-32. I agree with and credit Moriartys testimony.

Based on the documentary evidence in the record and Moriartys testimony, I find that the record boundary of Lot 9 is the edge of the bank and does not extend to the low-water mark, and that, therefore, the Disputed Area, consisting of the flats to the Pond between the bank and the low-water mark, is not part of Lot 9. Nothing in the 1890 Plan and 1898 Deed, or in any subsequent deeds or plans, states or shows the boundaries of Lot 9 going down to the low-water mark. To the contrary, there is a clear description in both the 1890 Plan and 1898 Deed demonstrating that the northerly boundary of Lot 9 is the edge of the bank. This is repeated over and over again throughout Evans chain of title. Deeds in the Jackpot Trusts chain of title reference the boundary of Lot 9 in their metes and bounds descriptions, as well as explicitly convey any flats and lands lying between the low-water mark of the Pond as shown in the 1890 Plan and 1904 Plan. Exhs. 28, 30, 32-34, 36. This further corroborates that the boundary of Lot 9 ends at the edge of the bank. For the foregoing reasons, I find and rule that the Jackpot Trust, not Evans, is the record owner of the Disputed Area.

B. Adverse Possession of the Disputed Area

Though I find the Jackpot Trust is the record owner of the Disputed Area and need not reach the issue of adverse possession, I discuss the Jackpot Trusts counterclaim nonetheless.

Title by adverse possession can be acquired only by proof of nonpermissive use which is actual, open, notorious, exclusive and adverse for twenty years. Ryan, 348 Mass. at 262. All these elements are essential to be proved, and the failure to establish any one of them is fatal to the validity of the claim. In weighing and applying the evidence in support of such a title, the acts of the wrongdoer are to be construed strictly, and the true owner is not to be barred of his right except upon clear proof of an actual occupancy, clear, definite, positive, and notorious. Cook v. Babcock, 65 Mass. 206 , 209-210 (1853). If any of these elements is left in doubt, the claimant cannot prevail. Mendoca v. Cities Serv. Oil Co. of Pennsylvania, 354 Mass. 323 , 326 (1968). The test for adverse possession is the degree and nature of control exercised over a disputed area, the character of the land, and the purposes for which the land is adapted. Ryan, 348 Mass. at 262. The claimant must demonstrate that he or she made changes upon the land that constitute such a control and dominion over the premises as to be readily considered acts similar to those which are usually and ordinarily associated with ownership. Peck v. Bigelow, 34 Mass. App. Ct. 551 , 556 (1993), quoting LaChance v. First Natl Bank & Trust Co. of Greenfield, 301 Mass. 488 , 491 (1938). The burden of proof in any adverse possession case rests on the claimant and extends to all of the necessary elements of such possession. Sea Pines Condo. III Ass'n v. Steffens, 61 Mass. App. Ct. 838 , 847 (2004). The Jacksons claims that the Jackpot Trust has acquired title to the Disputed Area through principles of adverse possession. The Jacksons assertion, therefore, turns on what activities were conducted in the Disputed Area over the twenty years prior to the filing of this action in July 2013.

In support of its claim, the Jackpot Trust introduced testimony from members of the Jackson family and tenants about activities that occurred on the Disputed Area. The activities described and shown in several photographs are consistent with, and typical of, uses associated with a familys use of a yard. Such activities in the Disputed Area included, numerous games (croquet, Frisbee, Jarts, badminton, kick-the-can), mowing and maintaining the lawn, shrubs and a privet hedge, storage of boats, laundry drying, yard waste disposal, cookouts, and reading and relaxing in a hammock. Later, in the 1990s, a jungle gym was placed in the Disputed Area for Mr. Jacksons grandchildren, who also built tree forts in the southeastern portion of the Disputed Area. These activities demonstrate dominion and control over the Disputed Area, indicating to others in the neighborhood that the Jackpot Trust and its predecessors were acting as the owners. The Jacksons did not in any way conceal their activities. Neighbors Abdulrazak and Andrews both testified to witnessing such activities and believed the Disputed Area belonged to the Jackson family. The Jackson family and their tenants were the exclusive users of the Disputed Area. No testimony was presented showing that others had used this area, nor that Evans or her predecessors had granted permission to the Jacksons to use the Disputed Area. Evans admits that prior to filing this action, she did not believe that she was the owner of the Disputed Area. The trial testimony from several witnesses indicates that the Jackpot Trust and their predecessors began using the Disputed Area approximately in the late 1950s or early 1960s and continued to use it frequently to the present. This is more than sufficient time to satisfy the statutorily required twenty year period for adverse possession. Based on the foregoing, I find that the Jackpot Trust and its predecessors actually, openly, notoriously, adversely, and exclusively occupied the Disputed Area for over twenty years.

However, this courts inquiry into the Jackpot Trusts adverse possession claim does not end there. When a claim of adverse possession is accompanied by a claim of title or a color of title, the possessor is asserting a claim of ownership based on an instrument, such as a deed, purporting to pass valid title, although it does not. Norton v. West, 8 Mass. App. Ct. 348 , 351 (1979). It is settled that where a person enters upon a parcel of land under a color of title and actually occupies a part of the premises described in the deed, his possession is not considered as limited to that part so actually occupied but gives him constructive possession of the entire

parcel. Dow v. Dow, 243 Mass. 587 , 593 (1923); Inhabitants of Nantucket v. Mitchell, 271 Mass. 62 , 68 (1930) (if adverse possession is established, the possessors ownership extends to the entire parcel described in the instrument and not just the part actually used and possessed). A successful claim under color of title requires (1) a successful adverse possession claim, and (2) proof that the claim of ownership is based on a document or writing of title. Long v. Wickett, 50 Mass. App. Ct. 380 , 382 n.3 (2000). This rule is grounded in the theory that it is the presumed intent of the grantee to assert such possession. See Norton, 8 Mass. App. Ct. at 351. The doctrine of color of title traces its origin to cases in which deeds, leases or other similar title instruments were ruled admissible to prove occupancy of land claimed by adverse possession, and as evidence of the nature of the claim asserted by the adverse user, and determined that this doctrine seems best suited to resolving the extent of a parcel claimed by adverse possession, where entry on land is made under an adverse claim and a deed or other title instrument is available to assist definition of the claim. Turturro v. Cheney, 6 LCR 293 , 297 (1998).

As previously noted, the Jackpot Trust has successfully demonstrated adverse possession to portions of the Disputed Area, at a minimum. Pursuant to the 1958 Deed, Paul Jones conveyed the Jackson Property to the Jackpot Trusts predecessor in interest, Michael Jackson, Sr. and Leslie Jones Jackson. The 1958 Deed references the 1958 Plan as well as recites the metes and bounds shown on the plan in its description of the lot. In 1976, Michael Jackson, Sr. and Leslie Jones Jackson conveyed the Jackson Property to the Fiduciary Trust Company, as Trustee of the Jackpot Trust. Again, the 1976 deed references the 1958 Plan and recites the metes and bounds shown on said plan in its description of the property. Evans does not contest that the descriptions of the Jackson Propertys boundaries in these deeds describe the property claimed by the Jackpot Trust, including the Disputed Area. Furthermore, the Jackpot Trust and its predecessors paid taxes on the Jackson Property and the assessors maps show the boundaries as including the Disputed Area. Accordingly, the Jackpot Trust entered the property under color of title and commenced their use upon the Jackson Property from around the late 1950s or early 1960s to the present. As such, I find that the Jackpot Trust has title to the entirety of the described parcel in its chain of title, including the Disputed Area, under the doctrine of adverse possession by color of title.

CONCLUSION

Judgment shall enter declaring that the Jackpot Trust is the record owner of the Disputed Area, and alternatively, the Jackpot Trust has acquired title to the entirety of the Disputed Area under the doctrine of color of title by adverse possession.

Judgment accordingly.

NANCY EVANS, Trustee of the NWW-2 Realty Trust v. MICHAEL J. JACKSON, JR. and JANE L. JACKSON, Trustee of the JACKPOT TRUST.

NANCY EVANS, Trustee of the NWW-2 Realty Trust v. MICHAEL J. JACKSON, JR. and JANE L. JACKSON, Trustee of the JACKPOT TRUST.