Walter J. Walsh (Walsh) is the beneficiary of the Trust he established to take title to property in Westwood he previously owned. In this action, he seeks to resolve a dispute with his next door neighbors, defendants Matthew J. Fitzgibbon and Cynthia Fitzgibbon (Fitzgibbons), over a disputed area along the boundary between their adjacent properties. The disputed area is approximately two feet wide and running 500 feet long, the distance of the length of the two properties. A portion of Walsh's driveway, which runs parallel along the shared boundary line, is within the disputed area. Walsh claims title to the disputed area based on a survey, and also ownership of the disputed area through adverse possession. The Fitzgibbons, relying on their own survey, contend that they are the owners of the disputed area. The parties seek a determination of the true common boundary line. After trial, I find that Walsh's surveyor accurately determined the location of common boundary line and based on that location, Walsh has ownership of the disputed area and the driveway does not encroach on the Fitzgibbons' property.

Procedural History

The complaint was filed on January 11, 2012, naming Walsh as plaintiff and the Fitzgibbons as defendants. Defendants' Answer and Counterclaims and Motion to Dismiss were filed on March 10, 2012. Plaintiff's Answer to Defendants' Counterclaims and Plaintiff's Opposition to Defendants' Motion to Dismiss were filed on March 20, 2012. The Motion to Dismiss was denied on July 31, 2012 for failure to comply with Land Court Rule 4. On May 15, 2015, Defendants' Motion to Amend and Add Counterclaims was filed. On June 16, 2015, the court allowed the Motion to Amend Counterclaim and deemed the counterclaim filed.

A pre-trial conference was held on September 3, 2015. On May 4, 2016, a view was taken and the first day of trial was held. The court allowed the Motion to Substitute Regina Walsh Sullivan, as Trustee of Walter J. Walsh Irrevocable Trust, as plaintiff in this action. Exhibits A through U were marked. Testimony was heard from Walter Walsh, Diane Walsh, and Connie Wu. The second day of trial was held on July 6, 2016. Exhibits B7 and B8 were marked. Testimony was heard from Paul DeLouis, Rod Carter, Cynthia Fitzgibbon, Matthew D. Smith, and Kenneth B. Anderson. Defendants' Motion for Mandatory Dismissal of Adverse Possession claim was heard and denied without prejudice, as was their Renewed Motion.

On September 8, 2016, Plaintiff's Requests for Findings of Fact (Pl. Facts), Plaintiff's Requests for Rulings of Law, Plaintiff's Post Trial Memorandum, Defendants' Requests for Findings of Fact (Def. Facts) and Rulings of Law, and Defendants' Post Trial Argument were filed. Closing arguments were heard on September 21, 2016, thereafter, the case was taken under advisement. This decision follows.

Findings of Fact

Based on the view, the undisputed facts, the exhibits, the testimony at trial, and my assessment of credibility, I make the following findings of fact.

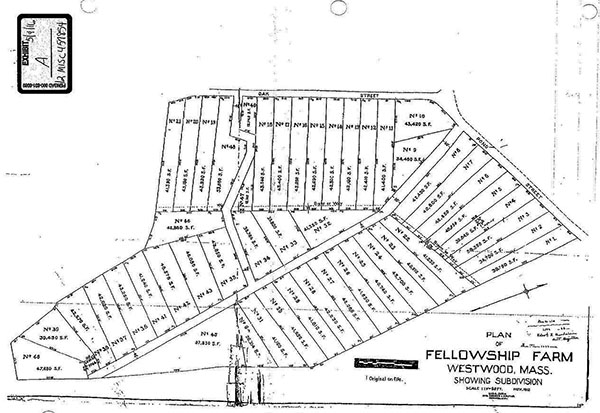

1. The properties at issue originate from a plan entitled "Plan of Fellowship Farm, Westwood, Mass. Showing Subdivision," dated November 1912 and recorded with the Norfolk Registry of Deeds (registry) as Plan No. 3152 in Plan Book 66 (Fellowship Plan). The Fellowship Plan is attached as Exhibit A. The Fellowship Plan shows eight original parcels along Pond Street in Westwood, Massachusetts (Fellowship Subdivision). The plan shows frontage distances along Pond Street, land area square footage, and distances along various dimensions, but does not contain angles or directions of courses. There are stakes depicted on the Fellowship Plan at the corners of some parcels, but many of those monuments have been obliterated. Exhs. A, U, ¶¶ 1, 5-6.

2. The eight lots of the Fellowship Subdivision along Pond Street are bounded by a stone wall along the eastern property line of Lot 1 and a 50 foot right of way known as Arcadia Road to the west of Lot 8. On the Fellowship Plan, the overall distance along Pond Street between the stone wall and the edge of Arcadia Road is depicted as 728 feet. Exhs. A, U, ¶¶ 7-8; Def. Facts, ¶¶ 7-8.

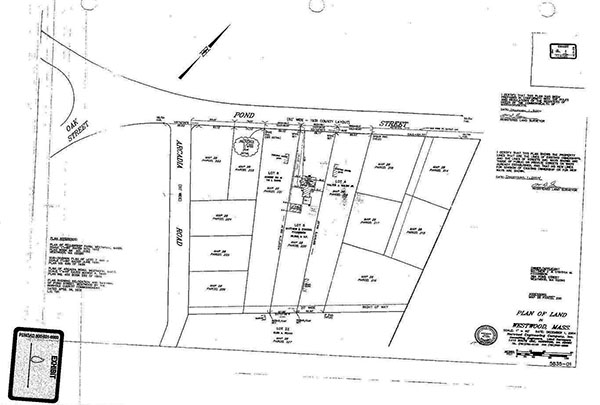

3. In 1931, Pond Street was widened through a taking by the Town of Westwood. The taking to widen Pond Street included taking a strip of land fronting Pond Street belonging to the eight lots in the Fellowship Subdivision. This taking is reflected in a plan dated April 28, 1931 and filed with the registry as Plan No. 332-335 in Plan Book 113 (Pond Street Plan). The Pond Street Plan shows the widening of Pond Street to a 60 foot width, the stone wall to the east, Arcadia Road to the west, and references to "S.B." (stone bounds) throughout the plan on Pond Street. Although not designated with an "S.B." on the Pond Street Plan, a bound is shown on the corner of Arcadia Road and Pond Street, on the side of Arcadia Road opposite Lot 8. That stone bound remains and has been located. Tr. 2:34, 42-43, 78, 141-142; Exhs. E, L, U, ¶¶ 9-10; Def. Facts, ¶ 9.

4. In the Pond Street Plan, a structure is shown on Lot 4 as belonging to Maud C. Rouillard and a structure is shown on Lot 5 as belonging to Herman Brandt. The Pond Street Plan also shows a stone wall in front of Lots 4 and 5, and a driveway going to Lot 4. Tr. 2:43-45; Exhs. E, U, ¶¶ 11-12.

5. Another plan entitled "Plan of Arcadia Road" dated March 6, 1980 and recorded with the registry as Plan No. 452 in Plan Book 282, shows the Pond Street layout as of the 1931 taking, with the width of Arcadia Road to be 50 feet (Arcadia Road Plan). The Arcadia Road Plan also depicts a stone bound on the corner of Arcadia Road and Pond Street on the opposite side of Lot 8. Exhs. L, U, ¶ 13.

6. Subsequent to the Pond Street expansion in 1931, there were a number of recorded plans that subdivided certain portions of the Fellowship Plan. Of the eight original parcels, Lots 4, 5, and 6 are the only parcels which have never been subdivided. Lots 1, 2, and 3 have since been reconfigured resulting in five smaller parcels. Lots 7 and 8 have also been reconfigured resulting in five smaller parcels. Tr. 2: 139, 149; Exhs. D, F, H, I, O, U, ¶¶ 31-32; Def. Facts, ¶ 11.

7. When he brought this action, Walsh was the owner of Lot 4 on the Fellowship Plan, having an address of 378 Pond Street, Westwood, Massachusetts, by a deed from Frank J. Marston and Mary P. Marston dated September 5, 1986, and recorded with the registry on in Book 7225, Page 708 (Walsh Property). On August 13, 2015, Walsh deeded the Walsh Property to Walter J. Walsh, Jr. as Trustee of the 378 Pond Street Realty Trust, by a deed recorded with the registry at Book 33405, Page 371. For health reasons, he then conveyed the Property to Regina Walsh Sullivan, as Trustee of the Walter J. Walsh Irrevocable Trust (Trust) by a deed recorded with the registry on March 1, 2016, in Book 33889, Page 293. Regina Walsh Sullivan (Sullivan) is the sister of Walsh and the sole trustee of the Trust. Sullivan has given Walsh full power and authority to maintain this action on behalf of the Trust and agrees to be fully bound by any decision of this court. Tr. 1:33-35; Pl. Facts, ¶¶ 1-6, 8; Def. Facts, ¶ 1-3; Exh. B, U, ¶ 2.

8. Walsh's former wife, Diane Walsh (Ms. Walsh), lived at the Walsh Property with him from 1988 to 2010. The Walsh Property is improved by three dwellings: the main house in the front of the property where Walsh resides, and two smaller dwellings in the rear of the property that Walsh rents out to tenants. When Walsh purchased Lot 4, there was a gravel driveway on the Walsh Property. The driveway was in a fairly straight line and traveled from Pond Street, past the main house, to the rear of the Walsh Property where the two rented dwellings are located. The driveway is used by Walsh and his tenants to access the dwellings and for parking. No testimony was given that anyone else besides the residents of the Walsh Property claimed a right to use the driveway. When he purchased the property in 1986, Walsh's mailboxes were located on the corner of his property and Pond Street. Shortly after moving in, Walsh relocated the mailboxes to an area west of his driveway along the shared boundary line with Lot 5. Tr. 1:34-35, 39-40, 47, 51-53; 68, 70 92-93; Tr. 2:17; Exhs. A, B, S12, S13; Def. Facts, ¶ 14; view.

9. The Fitzgibbons own Lot 5 on the Fellowship Plan, having an address of 384 Pond Street, by a deed from Paul S. DeLouis (DeLouis) dated June 19, 2002, and recorded with the registry in Book 16752, Page 182 (Fitzgibbon Property). Exhs. A, C, M, U, ¶¶ 3-4; Pl. Facts, ¶¶ 10-13; Def. Facts, ¶¶ 4-5.

10. DeLouis owned and occupied Lot 5, the Fitzgibbon Property, for 21 years between 1981 and 2002. In or about 1988 or 1989, DeLouis planted a small tree on what was believed to be the boundary line between Lots 4 and 5. In or around 1994, the structure shown on Lot 5 of the Pond Street Plan was razed and a new home was built by DeLouis. In connection with the construction of his new home, DeLouis retained the services of James P. Troupes to prepare an as-built foundation plan of the land (Troupes Plan). The Troupes Plan was not recorded. The Troupes Plan sets forth the distance from the northeastern corner of the dwelling on Lot 5 to the boundary of Lot 4 as 22 feet. Troupes installed several rebar markers along the boundaries of where he determined the location of the now Fitzgibbon Property. One rebar was installed in the northeast corner of the Fitzgibbon Property and the northwest corner of the Walsh Property at Pond Street, where Walsh's mailboxes are now located. DeLouis recalled a stone marker in the ground that he considered to be the boundary line between Lots 4 and 5. This was not found by subsequent surveyors. DeLouis stated that he did not rely on the Troupes Plan since it was only prepared as a foundational plan for the construction of his house, nor did he take any measurements in determining where he though the boundary line was located, but relied on the stone marker. After purchasing the property, the Fitzgibbons relied upon the Troupes Plan to set stakes and stretch rope along the property lines. Tr. 1:45-47; Tr. 2: 11-15, 18-21, 99-100; Exhs. M, R3, S12, U, ¶¶ 14-16; Pl. Facts, ¶¶ 49-52; Def. Facts, ¶ 13.

11. In June 2003, Walsh paved over his gravel driveway. Walsh hired Bevilaqua Paving and instructed them to install a string guide from a fence post to his mailbox post, against an existing piece of rebar located on what he believed was the common boundary line. Orange spray paint was used to paint a line on the ground approximately 1.5 feet inside the property line. The piece of rebar, which can be seen in photographs from 2003, was no longer present the following year. Tr. 1:47-50, 71-72, 75-77, 91; Tr. 2:101-102; Exhs. R3, S; Pl. Facts, ¶ 53; view.

12. The Walshes testified that once the asphalt was laid they did not take any measurements or do anything to verify whether the new driveway was in a different location than the gravel driveway, closer to the Fitzgibbon Property. Though the Walshes and DeLouis testified that the paved driveway was installed in the same location as the gravel driveway that had existed at least since 1981, this was based on their general observations and recollection of the location of the gravel driveway as none were present to witness the paving. No other evidence was presented as to the prior location of the gravel driveway in relation to the paved driveway. I do not credit their testimony. Tr. 1:47-48, 68-72, 77, 89-90, 106-109; Tr. 2:15-16, 22-23; view.

13. Ms. Fitzgibbon was at her home next door when the driveway was paved and witnessed Bevilaqua Paving installing the string line and spraying the orange spray paint. She testified that they first distributed a layer of gravel subsurface over the existing gravel driveway, which spilled onto her property. Ms. Fitzgibbon took pictures and measurements of the distance from the northeast corner of her house to the common boundary line and found that, according to the 22 foot distance shown in the Troupes Plan, the paved driveway encroached onto her property. She stated that when the driveway was paved it was made wider than previously. The configuration of the driveway had changed, shifting it westward so that it now curves inward toward her house. Ms. Fitzgibbon testified that when she first moved in 2002, she did not observe any encroachment of the gravel driveway based on her understanding of where the property line was and the gravel driveway was straight. Based on the view and my assessment of credibility, I credit Ms. Fitzgibbon's testimony and find that the gravel driveway was widened and moved closer to the Fitzgibbon Property when it was paved. Tr. 2:103-109, 111-113; Exhs. R, S; Pl. Facts, ¶ 53; Def. Facts, ¶¶ 15-18; view.

14. After the Fitzgibbons purchased their property, questions arose about the location of the boundary line between the Fitzgibbon Property and the abutting property to the west, Lot 6 on the Fellowship Plan, belonging to Tai I. Dong and Connie Wu (Dong/Wu Property). The Fitzgibbons approached Walsh and asked if he would be willing to share in the cost to have the properties surveyed. Walsh declined. Tr. 1:59, 119-120, 127-128; Exh. U, ¶¶ 17-18; Pl. Facts, ¶ 17.

15. In November 2004, Chester Redmond (Redmond) of Commonwealth Engineering prepared a survey for Tai I. Dong and Connie Wu and set two P.K. masonry nails where he believed the corners of Lot 6 along Pond Street were located (Redmond Plan). The northeast corner appeared to be within the Fitzgibbons' driveway. Tr. 1:122-123; Exh. N; Pl. Facts, ¶¶ 18- 19.

16. Ms. Fitzgibbon did not agree with the Redmond Plan and filed a complaint with the Board of Licensure (Board) against Redmond. Redmond's license was suspended as a result of an investigation by the Board. Tr. 1:80-81, 84, 87, 123-124; Exh. N; Pl. Facts, ¶¶ 20-21.

17. Believing the Redmond Plan to be incorrect, the Fitzgibbons retained the services of Norwood Engineering in December 2004 to research and prepare a plan determining the location and dimensions of the Fitzgibbon Property. Matthew D. Smith (Smith) from Norwood Engineering, a professional licensed engineer since 1992 and professional licensed surveyor since 2002, found certain monuments in the field and based on those monuments, as well as other evidence, set spikes at the northern corners and set rebar/caps at the southern corners of the Fitzgibbon Property (Smith Plan). The Smith Plan was recorded with the registry on December 10, 2004, as Plan No. 54 in Plan Book 531. The Smith Plan is attached as Exhibit B. Tr. 2:112- 113, 136-137, 140-141; Exhs. O, U, ¶¶ 19-21; Pl. Facts, ¶¶ 22, 26; Def. Facts, ¶¶ 19-20, 25.

18. In performing his survey, Smith used the measurements provided in the deeds for parcels comprising the land originally depicted as Lots 7 and 8. Smith was not able to locate the P.K. masonry nail set by Redmond the month prior located at the northeast corner of the Dong/Wu Property and the northwest corner of the Fitzgibbon Property, but he did find the P.K. nail set by Redmond at the northwest corner of the Dong/Wu Property. Smith did not hold this nail because, he found, the true corner is approximately 1.68 inches from the mathematical corner described in the subject deeds. Tr. 2:144; Exh. O; Pl. Facts, ¶ 40; Def. Facts, ¶ 21; view.

19. Smith also found and held two survey markers at the westernmost corners of the original Lot 3. Smith found and held rebar at what he believed was the northeast corner of the Walsh property and the northwestern corner of what was previously Lot 3, though there is no recorded plan that shows a rebar or any other monument in that location. These markers coincided with the subsequent subdivision of Lots 1, 2, and 3. Smith did not find the rebar used by Bevilaqua Paving when the driveway was paved the prior year, nor did he find the stone marker along the common boundary line DeLouis recalled. Tr. 2:145; Exhs. O, R3; Pl. Facts, ¶¶ 41-42; Def. Facts, ¶ 22; view.

20. In generating his plan, Smith discovered that the distance on the ground along Pond Street between the stone wall and Arcadia Road, namely the frontage of Lots 1-8 on the Fellowship Plan, was not 728 feet as shown on the Fellowship Plan. Smith testified that he found a shortage of 4.82 feet along Pond Street, but nowhere on the Smith Plan does it show his measured distance between the stone wall and Arcadia Road. Smith's testimony does not clarify how he obtained this figure as the shortage amount. He stated that the western boundary of the original eight lots shown on the Fellowship Plan was unascertainable because there is no means by which to identify the location of Arcadia Road in 1912 when the Fellowship Plan was created. Smith testified that he came up with different distances for the length of Pond Street from the stone wall to Arcadia Road depending on if he measured westerly from the stone wall or if he measured easterly from Arcadia Road. The Smith Plan does not identify a distance from the stone wall to any of the monuments Smith found in the field. Tr. 2:77-79; Pl. Facts, ¶ 45.

21. Facing the shortage found along Pond Street, Smith used the technique of prorating the shortage among the eight lots fronting Pond Street to account for the deficiency on the ground. Having identified that the Fellowship Subdivision's easternmost and westernmost lots on Pond Street had been subsequently subdivided and that, in his opinion, occupational lines were in accordance therewith, Smith "made the call" to maintain the boundaries of these subsequent subdivisions and apportion the deficiency equally among Lots 4, 5, and 6, the middle lots that had not been subdivided. Holding the boundaries of Lots 1, 2, 3 and Lots 7 and 8 to the locations depicted in their respective subdivision plans, Smith stated that he apportioned 1.7 feet to Lots 4, 5, and 6, and allocated the remaining shortage to Lots 1, 2, and 3. Smith stated that he used this method because it agreed with different monuments he found along Pond Street. Based on the Smith Plan, the common boundary line between the Walsh and Fitzgibbon Properties is located approximately two feet east of its present location as shown on the Fellowship Plan, meaning that a 31-square-foot portion of Walsh's paved driveway encroaches onto the Fitzgibbon Property. No plan showing how the driveway allegedly encroaches on the Fitzgibbon Property was submitted. Smith found the distance from the northeast corner of the house on the Fitzgibbon Property to the common boundary line to be 22.5 feet, about the same distance as shown on the Troupes Plan. Tr. 2:139, 144 -145, 147-149, 153; Def. Facts, ¶¶ 23-24.

22. The Fitzgibbons did not discuss the Smith Plan with Walsh prior to recording it and never provided Walsh with a copy of the plan. After recording the Smith Plan, the Fitzgibbons placed various markers in what they perceived to be the true property line, including a portion of Walsh's driveway. These markers included bricks, strings, and rebar. In a letter dated May 6, 2005, the Fitzgibbons approached the Walshes and asked if they could execute a document acknowledging the Fitzgibbons' determination of the property line based on the Smith Plan. The letter also gave permission to the Walshes to use the encroaching sections, such as the driveway and mailbox areas, so long as they confirmed the location of the shared boundary based on the Smith Plan. The Walshes were not provided a copy of the Smith Plan. The Walshes acknowledged that there was a boundary dispute, but they declined to sign the letter. Tr. 1:54-55, 59, 94-99, 103-104, 110-112, 118-120; Exhs. R4, T, U, ¶¶ 22-23; Pl. Facts, ¶ 32.

23. After receiving the letter from the Fitzgibbons in 2005, and believing that the Smith Plan was incorrect, Walsh retained the services of Rod Carter of Rod Carter Associates (Carter) to investigate and make a determination of the boundary line between the Fitzgibbon Property and the Walsh Property. Carter made preliminary drafts of a plan as more information became available, but no draft was recorded. As with Redmond, Ms. Fitzgibbon did not agree with one of Carter's preliminary survey results and filed a complaint with the Board. The Board requested a meeting with Carter regarding a 2009 draft survey of the properties. Upon discussions with his mentor, Carter produced a revised plan that was ultimately relied on by Walsh in this action. The Board took no action against Carter. Tr. 1:61, 78-80; Tr. 2:27-28, 72, 75, 79-80, 86-87; Exh. U, ¶¶ 24-25; Pl. Facts, ¶ 35; Def. Facts, ¶ 31.

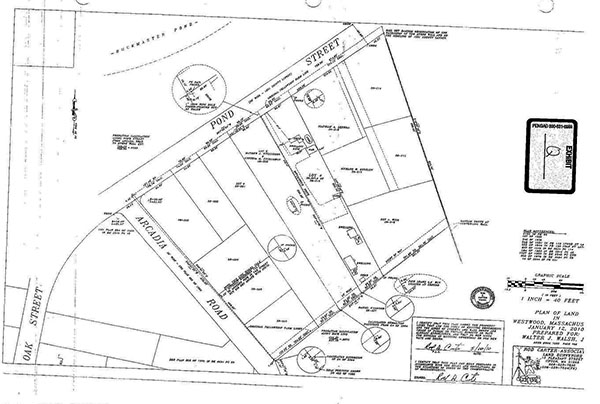

24. The final plan by Carter is dated January 12, 2010, and was signed May 10, 2010 (Carter Plan). The Carter Plan was not recorded. Carter found numerous markers in the area. He found three stone bounds along Pond Street that were installed during the 1931 taking and shown on the Pond Street Plan. Carter found an iron pipe at the northeast corner of the Walsh Property, a P.K. nail at the northwest corner of the Walsh Property, and an iron pipe at the southeast corner of the Walsh Property. Though he found neither the rebar used when the driveway was paved in 2003, nor the stone marker along the boundary line that DeLouis recalled, he did find an iron pipe along the shared boundary line. Carter did not hold any of these markers as monuments, but merely used them as reference points to confirm his ultimate conclusion about the location of the property line. Carter testified that the most significant monument was the stone wall. The Carter Plan is attached as Exhibit C. Tr. 1:61-64; Tr. 2:37-40, 72, 75; Exhs. R5, U, ¶ 26; Pl. Facts, ¶¶ 33-36; Def. Facts, ¶¶ 29-30.

25. When Walsh purchased the property in 1986 from Frank J. Marston and Mary P. Marston, Walsh was shown as many as six markers designating what he was informed was his property lines, but Walsh had no knowledge of the origin of the markers. Many of the markers shown to Walsh have been removed by someone. Ms. Fitzgibbon has admitted to removing and replacing one or more monuments designating the property lines over the years, but she stated she never removed any markers that she believed were placed by a surveyor. Ms. Fitzgibbon also installed a few markers herself along where she believed her property line was located. I find that Ms. Fitzgibbons did remove certain monuments along the shared property lines with the Walsh Property and the Dong/Wu Property and that Carter's failure to find certain markers does not cut against his ultimate findings. Tr. 1:33-35, 57, 66-67; Tr. 2:114-120; Exh. R4; Pl. Facts, ¶¶ 14-16.

26. Like Smith, Carter also found that the actual distance on the ground along Pond Street along Lots 1-8 between the stone wall and Arcadia Road was not 728 feet as shown on the Fellowship Plan. Carter's survey found a shortage of 4.45 feet (as compared to Smith's 4.82-foot shortage) on the ground compared to the distance shown on the Fellowship Plan. Carter calculated this shortage by measuring from the stone wall bounding the eastern side of the Fellowship Subdivision to a stone bound on the opposite side of Arcadia Road because he could not locate the bound on the northeast corner of Arcadia Road and the northwest corner of Lot 8. This stone bound is shown on the Arcadia Road Plan. Carter testified that this bound was likely set by the Town of Westwood or Norfolk County at the time of the 1931 taking of Pond Street. Carter also used the technique of proration to account for the deficiency on the ground. In contrast to Smith, Carter chose to apportion the deficiency across all eight of the original lots along Pond Street belonging to the Fellowship Subdivision, and subject to the 1931 taking, in proportion to their areas. He did not take the subsequent subdivisions of the Fellowship Subdivision into consideration. Based on the apportionment in the Carter Plan, the common boundary line between the Walsh and Fitzgibbon Properties is not two feet east of its present location, but is rather in roughly the same location, meaning that the Walsh's driveway is entirely on the Walsh Property. Tr. 2:34-36, 42-43, 63, 76-77, 90-91; Exh. U, ¶ 29; Def. Facts, ¶¶ 33-34, 36; view.

27. Due to differences in the method of apportionment, the Smith Plan and Carter Plan conflict as to the location of the shared property line between the Fitzgibbon Property and the Walsh Property. The Fitzgibbons argue that the Smith Plan is the correct survey of the common boundary line. Walsh argues that the Carter Plan is the correct survey of the boundary line. The difference in the location of the boundary line between the two surveys comprises an area about two feet wide and running the length of the shared boundary, about 500 feet, making the total area approximately 1000 square feet (Disputed Area). As discussed further below, I do not credit Smith's method of apportionment in holding certain property lines on lots subject to the deficiency based on subsequent subdivisions. I credit Carter's methodology in apportioning the deficiency across all original eight lots that were subject to the original shortage and the 1931 taking in determining the location of the shared boundary line. I find that neither Walsh's driveway, nor any other structure belonging to Walsh, encroaches onto the Fitzgibbon Property.

28. The Fitzgibbons retained Kenneth B. Anderson (Anderson), a registered professional land surveyor, to opine as to the correct methodology for surveying the properties and apportioning the deficiency among the lots. Anderson stated that the only monument shown on the Fellowship Plan is the stone wall. He stated that the western boundary of the original eight lots in the Fellowship Subdivision unascertainable because there is no means by which to identify the location of Arcadia Road in 1912 when the Fellowship Plan was created. He opined that when doing a retracement survey, it is appropriate to locate anything and everything that can be found in or around the area. Anderson endorsed Smith's methodology of proration, testifying that Smith's decision to apportion across only the three center lots was "the only correct way he could apportion." Neither Anderson nor Smith cited to any surveying guidelines or cases to support this methodology of proration. Anderson also did not agree with Smith's allocation of the remaining shortage to Lots 1, 2, and 3 and could come up with no explanation for why Smith did this. I do not credit Anderson's endorsement of the Smith Plan. I do credit his testimony in so much as he disagreed with Smith's proration of the remaining deficiency to Lots 1, 2, and 3. Tr. 2:183-186, 192-193, 196-197; Pl. Facts, ¶¶ 56-63; Def. Facts, ¶¶ 26-27, 35.

Discussion

This case concerns the location of a common boundary line between the Walsh Property and the Fitzgibbon Property. "The location of a disputed boundary line is a question of fact to be determined on all the evidence, including the various surveys and plans, and the actual occupation and use[s] by the parties.'" Ellis v. Ashwood Realty LLC, 19 LCR 520 , 523 (2011), citing Hurlbut Rogers Machinery Co. v. Boston & Maine R.R., 235 Mass. 402 , 403 (1920); see Paull v. Kelly, 62 Mass. App. Ct. 673 , 679 (2004). "When presented with expert surveying and title testimony, a court must assess the opinions offered. The court must decide which . . . expert it finds more credible basing such assessment on the experts' analysis, taking into account the other evidence presented, including the documentary evidence, particularly the deeds and plans that lend support and corroboration to each opinion." Cytrynowski v. McDonald, 24 LCR 503 , 508 (2016) (appeal pending, No. 2016-A-1450), quoting Lombard v. Cook, 20 LCR 325 , 326 (2012). "No surveyor or court has authority to alter or modify a boundary line once it is created. It can only be interpreted from evidence of where that boundary is located." Id., quoting Brown's Boundary Control and Legal Principles, 382 (7th ed. 2014) (hereinafter "Brown"). "The law does not require absolute certainty of proof to determine a boundary line, but merely a preponderance of the evidence." Id., citing McCarthy v. McDermott, 18 LCR 405 , 406 (2010).

Here, there is not enough land within the platted tract along Pond Street to supply all the eight lots with the dimensions given on the Fellowship Plan. While the Fellowship Plan was probably correct when prepared in 1912, the 1931 taking accompanying the widening of Pond Street reduced the dimensions of Lots 1-8 as they abut the widened Pond Street. That reduction was not reflected in subsequent plans or deeds, but nevertheless exists on the ground. "When surveys reveal that the allotted distances do not match the reality on the ground, courts must decide how to apportion the excess or deficiency of land." Leahy v. Glukhovsky, 20 LCR 429 , 436 (2012). Where, after a tract of land is subdivided into lots and title vested in different persons, it is discovered that the original tract contained either more or less than the area assigned to it in a plan or prior deed, the excess or the deficiency generally is apportioned among all of the subdivided lots in proportion to their areas. Patton and Palomar on Land Title § 161 (3d ed.) (hereinafter "Patton"); see Long v. Merrill, 24 Pick. 157 , 162-163 (1839); Brown, 388-389. Typically, the discrepancy is computed between two fixed or known monuments and apportioned to the intervening tracts only, it being presumed that the discrepancy came from an imperfect measurement of the whole line and not a particular portion of it. Patton § 161, citing 11 C.J.S., Boundaries § 141; Leahy, 20 LCR at 436; Brown, 415 ("The original surveyor probably had a chain that was either too long or too short, and the error would occur in parts of the line."); Am. Jur. 2d Boundaries § 52. "Where a subdivision shows [multiple] lots of equal frontage, it is logical to assume that any small excess or deficiency should be distributed among all lots equally." Brown, 415. "The variances will be apportioned among all the subdivisions, in accordance with the general rule, whenever it appears that the several conveyances were intended to comprise the entire tract." Patton § 161.

"[T]his rule is only to be availed of when the land is conveyed by reference to a plan, or there is some declaration in the deed indicating a purpose to divide the land according to some definite proportion, and when there also is no other guide to determine the locations of the respective lots." Bloch v. Pfaff, 101 Mass. 535 , 538 (1869); Marsters v. Alden, No. 131242, 1990 WL 10093956, at *5 (Mass. Land Ct. Aug. 21, 1990) ("The usual rule in Massachusetts, absent a plan, is that the excess land in a parcel if that were the problem or a deficiency if that is the case is gained or borne by the last grantee."); cf. Hughes v. Yates, 228 Ark. 860, 86364 (1958) (general principal of apportionment not applicable where there was no plat nor any reference in the deed to a comprehensive plan). Where, therefore, the original corners of a lot can be found, it is not affected by any discrepancy in the size of the block in which it is located. Patton § 161, citing Williams v. St. Louis, 120 Mo. 403 (1894) (holding that a street should not be moved to apportion a share of the excess in a platted subdivision to lots lying between monuments since the lots had the correct number of feet on the ground that their deeds called for, i.e., monuments control over distances). But if the available evidence locates only the corner of the block, the excess or deficiency must be distributed to the several lots in proportion to their platted widths. Id. Here, the deeds in the parties' respective chains of title consistently bound their properties by reference to lots shown on the Fellowship Plan, Exhs. B, C, and it is therefore appropriate to apply rules of apportionment to account for the deficiency.

"The effect of these rules is that, while remote grantees of the original proprietor of a plat bear the loss of any deficiencies that exist in the size of their lots, they own any excess area properly apportioned to their lots, without specific conveyance from the proprietor." Patton

§ 161 (grantor intended to convey the entire tract and not retain any excess). "Such is not, however, the apparent intention when an owner conveys a tract to successive purchasers by metes and bounds descriptions or by definite quantities. In such cases, any deficiency falls on the proprietor, or upon his last purchaser, and the title to any surplus remains in the former. But, if the last conveyance shows an intention to convey the entire balance of the tract, any surplus goes to his last purchaser." Patton § 161, citing Bloch, 101 Mass. at 538; see also Sorenson v. Mosbacher, 230 N.W. 656, 657 (Iowa 1930). Some courts have refused to apportion property contrary to existing lines of possession. See Allen v. City of Mt. Morris, 32 Mich. Ct. App. 633 (1971); Anderson v. Wirth, 131 Mich. 183 (1902). "Any situation involving an excess or deficiency, or omitted strips, should alert the examiner to consider several possibilities that may additionally affect title, such as adverse possession, or the doctrines of practical construction." See Reitz v. Knight, 62 Wash. App. 575 (1991); Brinson v. Shimp, 574 So. 2d 1105 (Fla. App. 1990).

Both parties agree as to the location of the edge of Pond Street after the widening in 1931, but disagree as to how the deficiency along Pond Street should be prorated across the lots. The parties have presented two competing surveys in which the method of apportioning the deficiency among the eight lots abutting Pond Street differed. The Carter Plan apportioned the deficiency among all of the original eight lots in proportion to their areas, placing the entirety of the Walsh driveway and all structures within the Walsh Property. In contrast, the Smith Plan apportioned the some of the deficiency among the middle three lots, Lots 4, 5, and 6, and the remainder to Lots 1, 2 and 3, moving the common boundary line about two feet east and placing some of the Walsh driveway upon land purportedly belonging to the Fitzgibbons. As discussed further below, I find that the correct location of the common boundary line between Lots 4 and 5 is that identified in the Carter Plan.

Carter used the more appropriate methodology in locating the position of the common boundary line. Both the Walsh Property and the Fitzgibbon Property originate from the 1912 Fellowship Plan, which depicts eight lots fronting Pond Street. Carter reviewed all the frontages in the deeds of the lots along Pond Street, beginning at the stone wall shown on the Fellowship Plan and continuing to Arcadia Road. When all the frontages were added together, Carter found that the distance on the ground between the stone wall and the edge of Arcadia Road was not 728 feet as stated in the 1912 Fellowship Plan. Carter determined that there was a shortage of 4.45 feet on the ground compared to the distance shown on the Fellowship Plan. Carter calculated this shortage by measuring from the stone wall bounding the eastern side of the Fellowship Subdivision to a stone bound on the opposite side of Arcadia Road that was set by the Town when the 1931 widening of Pond Street occurred, taking into account the width of Arcadia Road layout as set forth in the Fellowship Plan. He had to use the stone bound on the other side of Arcadia Road because he could not locate the bound on the northeast corner of Arcadia Road and the northwest corner of Lot 8. Carter determined that the most appropriate method to split up the 4.45 feet shortage was to spread it proportionally across all eight original lots. He determined that each original lot would receive .9939% of its intended frontage on Pond Street to accommodate the shortage. See Leahy, 20 LCR at 436. After prorating the deficiency, the Carter Plan established the location of the common boundary, finding that the driveway and all structures belonging to Walsh are within the Walsh Property.

The Fitzgibbons argue, and both Smith and Anderson testified, that the use of the stone bound on the side of Arcadia Road opposite from Lot 8 was improper because it was not a fixed monument shown in the Fellowship Plan. They assert that there is no means to ascertain the location of Arcadia Road in 1912. With the stone wall being the only original monument held, the Fitzgibbons contend that it was improper to apportion the deficiency across all eight original lots since a deficiency can only be distributed across all lots when the deficiency exists "in a straight line between fixed monuments within a subdivision." Leahy, 20 LCR at 436. Because there was only one original monument from 1912, they maintain that the apportionment in the Carter Plan was not appropriate. This argument fails.

Although the stone bound on Arcadia Road was not shown on the Fellowship Plan, Carter's reliance on it to determine the deficiency and apportion it across all the lots was proper. "Rules of deed construction provide a hierarchy of priorities for interpreting descriptions in a deed. Descriptions that refer to monuments control over those that use courses and distances; descriptions that refer to courses and distances control over those that use area; and descriptions by area seldom are a controlling factor." Paull, 62 Mass. App. Ct. at 680. Adjoining land referenced in the description of a deed is a monument "even though there is no visible evidence of such line upon the land." M.E. and D.D. Park, Real Estate Law § 249 (2d. ed. 1981); Paull, 62 Mass. App. Ct. at 680; Temple v. Benson, 213 Mass. 128 , 132 (1912). "Monuments, when verifiable, are thus the most significant evidence to be considered." Ouellette v. McInerney, 19 LCR 41 , 42 (2011). Once a fixed monument is found and located, the courses of the respective properties can be accurately determined by reference to it. Raymond v. Jackson, 257 Mass. 509 (1937). The 50 foot right of way to the west of Lot 8, later to be known as Arcadia Road, was referenced in deeds to lots in the Fellowship Subdivision and shown on the Fellowship Plan. The stone bound on Arcadia Road, relied on by Carter, was placed there in 1931, as shown on the Pond Street Plan, in conjunction with the taking on Pond Street. The stone bound and the 50 foot width of Arcadia Road are also depicted on the Arcadia Road Plan recorded in 1980, which shows the county layout of Pond Street from the 1931 taking. It can be inferred that the Town would have been precise in their surveying of Arcadia Road in connection with their taking of Pond Street. Where monuments are identified in recorded plans and located in the field at the locations depicted in those plans, they should control. See Edeman v. Corsano, 15 LCR 657 , 659 (2007), citing Morse v. Chase, 305 Mass. 504 , 507 (1940).

Based on this evidence, I find that the stone bound shown on the Pond Street Plan and the Arcadia Road Plan accurately defines the western boundary of Arcadia Road and that it was proper for Carter to use this stone bound as a fixed monument for purposes of apportionment and verifying the common boundary line. The use of the stone bound was also appropriate considering that all eight lots in the Fellowship Subdivision were subject to the 1931 taking, which eliminated some of their frontage and affected the location of the side boundaries of Lots 1-8 on Pond Street. Carter properly did not take into consideration the subdivisions of the eight lots of the Fellowship Subdivision. These subdivisions were all made after the 1931 taking, and, therefore, this is not the case of the last purchaser where all remaining lots not subdivided out of the original parcels would be responsible for carrying the overall deficiency along the street. There is no evidence suggesting that the original grantors of the Fellowship Subdivision intended only certain parcels to bear the loss.

Additionally, Carter found numerous markers in the area of the Walsh Property that corroborate his method of apportioning the shortage among all the lots. He found an iron pipe where he located the northeast corner of the Walsh Property, a P.K. nail where he located the northwest corner of the Walsh Property, and an iron pipe where he located the southeast corner of the Walsh Property. Though he did not find the rebar used when the driveway was paved in 2003, nor the stone marker along the boundary line that DeLouis recalled, he did find an iron pipe along the shared boundary line. Carter did not hold any of these markers as monuments, but merely used them as reference points in confirming where he ascertained the location of the boundary between the Walsh and Fitzgibbon Properties.

Conversely, Smith did consider the effect of the post-1931 taking subdivisions of the original eight lots. Smith testified that he found a shortage of 4.82 feet along Pond Street. Smith's testimony does not clarify how he obtained this figure as the shortage amount, though it is close to the shortage found by Carter. Nowhere on the Smith Plan does it show the distance between the stone wall and Arcadia Road. Smith testified that he came up with different distances for the length of Pond Street from the stone wall to Arcadia Road depending on if he measured westerly from the stone wall or if he measured easterly from Arcadia Road. The Smith Plan does not identify a distance from the stone wall to any of the monuments Smith found in the field. Having identified that the Fellowship Subdivision's easternmost and westernmost lots on Pond Street had been subsequently subdivided and that, in his opinion, occupational lines were in accordance therewith, Smith "made the call" to hold the boundaries of these subsequent subdivisions and apportion 1.7 feet of the 4.82 feet deficiency equally among Lots 4, 5, and 6, which had never been subdivided. Smith stated that he allocated the remaining shortage to Lots 1, 2, and 3, but offered no support for why he did this. Anderson, a registered professional land surveyor who generally endorsed Smith's method of proration, disagreed with this allocation. While Smith stated that he used this method because it agreed with different monuments he found along Pond Street, he failed to find certain key monuments and relied on several unverifiable monuments. He only located monuments in the field that he believed fit mathematically with where the corners of the lots should be based on his method of proration.

Unlike Carter, Smith did not locate the iron pipe in the northeast corner of the Walsh Property or the P.K. nail in the northwest corner of the Walsh Property. He was not able to locate the P.K. masonry nail set by Redmond the month prior to his survey, located at the northeast corner of the Dong/Wu Property and the northwest corner of the Fitzgibbon Property. Smith did find the P.K. nail set by Redmond at the northwest corner of the Dong/Wu Property. Though he did not hold this nail because he found it to be approximately 1.68 inches from the mathematical corner described in the subject deeds, he testified that he relied on it as confirmation of his apportionment method because it was close enough. [Note 1] In addition, Smith found and held rebar at what he believed was the northeast corner of the Walsh property and the northwest corner of what was previously Lot 3, though there is no recorded plan depicting a rebar or any other monument in that location. The monuments found by Smith coincided with the subsequent subdivision of the lots out of the original Fellowship Subdivision. While Smith, like Carter, did not find the rebar used when the driveway was paved the prior year, nor did he find the stone marker along the boundary line that DeLouis recalled, he also did not find the iron pipe on the common boundary line between the Walsh and Fitzgibbon Properties that was found by Carter. Overall, Smith primarily relied on two unverifiable monuments to support his apportionment, the rebar located at what he believed was the northeast corner of the Walsh property and the P.K. nail set by Redmond at the northwest corner of the Dong/Wu Property.

The evidence in the record supports a conclusion contrary to Smith's findings. Smith used flawed and inconsistently-applied logic to arrive at his ultimate outcome. Smith testified that in using his own methodology, he arrived at different distances for the length of frontage on Pond Street depending on if he measured west to east or east to west. Smith worked his way eastward from Lot 8 to the stone wall using distances found on recorded subdivision and layout plans, then prorated only 1.7 feet to Lots 4, 5, and 6. When he could not fit the remaining distance to the stone wall in line with the location of the rest of the parcels, he prorated the remainder of the 4.82 feet to Lots 1, 2, and 3, which Anderson testified was incorrect. Smith's decision to use apportionment only on a selected portion of the original eight lots in the Fellowship Subdivision, while holding lines from subsequent subdivisions of the original lots, is unsupported by any law or surveying practices for apportionment. Neither Smith nor Anderson testified as to when such methodology would be appropriate and the court is aware of no case where such a partial application of proration was utilized. Under Smith's logic, a known shortage could be placed upon a single parcel that had not yet been subdivided while other parcels that had been previously subdivided would bear no loss from any deficiency. This outcome is untenable. Where all lots along a street suffer from the same original deficiency prior to being subdivided, the burden of the deficiency should be borne by all lots and not simply on those that have retained their original identity.

Carter used a more well-practiced methodology in arriving at his conclusion. He conducted extensive research and tied his findings into verified monuments shown on other plans, which he found in the field. Carter did not rely on monuments that were erroneous or otherwise unreliable. His method is further strengthened by examples of Massachusetts cases where proration has been applied in similar circumstances. See Bloch, 101 Mass. at 538; Leahy, 20 LCR at 436. These decisions make no exception for subsequent subdivisions when attempting to reconcile a shortage in determining a boundary dispute. I find that Carter applied the appropriate method of proration for the shortage along Pond Street, and adopt the common boundary line as determined in the Carter Plan. Accordingly, the Trust is the record owner of the Disputed Area.

The Trust alternatively argues that it owns the Disputed Area through principles of adverse possession. It appears that Walsh improperly brought this case as a try title action under G.L. c. 240, §§ 1-5, when, in fact, the relief he apparently seeks is actually to establish title to the Disputed Area through his claim of adverse possession, pursuant to G.L. c. 240, §§ 6-10. Specifically, the complaint asserts that Walsh and later the Trust acquired title to the Disputed Area by adverse possession and requests a decree of this court that it be declared and adjudged that the Trust is the owner of the Disputed Area. Although I find that the Trust is the record owner of the Disputed Area, because the Trust has raised this issue, I will briefly address the adverse possession allegations.

"Title by adverse possession can be acquired only by proof of nonpermissive use which is actual, open, notorious, exclusive and adverse for twenty years." Ryan v. Stavros, 348 Mass. 251 , 262 (1964). "All these elements are essential to be proved, and the failure to establish any one of them is fatal to the validity of the claim. In weighing and applying the evidence in support of such a title, the acts of the wrongdoer are to be construed strictly, and the true owner is not to be barred of his right except upon clear proof of an actual occupancy, clear, definite, positive, and notorious." Cook v. Babcock, 65 Mass. 206 , 209-210 (1853). "If any of these elements is left in doubt, the claimant cannot prevail." Mendoca v. Cities Serv. Oil Co. of Pa., 354 Mass. 323 , 326 (1968) (internal citations omitted). The test for adverse possession is the degree and nature of control exercised over a disputed area, the character of the land, and the purposes for which the land is adapted. Ryan, 348 Mass. at 262. "The burden of proof in any adverse possession case rests on the claimant and extends to all of the necessary elements of such possession." Sea Pines Condo. III Ass'n v. Steffens, 61 Mass. App. Ct. 838 , 847 (2004).

In order to prevail on its adverse possession claim, the Trust must establish 20 continuous years of open, notorious, adverse, and exclusive use of the Disputed Area. At trial, the Trust failed to meet its burden to establish title by adverse possession to the entire Disputed Area. No plan was ever produced depicting the alleged adverse possession area to which the Trust is claiming title. No evidence was presented as to Walsh's use of the Disputed Area, except in regards to the portion of the driveway and his mailboxes that are within the Disputed Area. Walsh has lived and owned the Walsh Property since 1986, only recently transferring ownership to the Trust. Testimony by DeLouis, who owned and occupied the now Fitzgibbon Property for 21 years, from 1981 to 2002, before selling to the Fitzgibbons, established that the gravel driveway on the Walsh Property, which led from Pond Street toward the rear of his property,

existed at least as early as 1981. The gravel driveway was used by Walsh's predecessors in title, the Walshes, and Walsh's tenants to access the dwellings and for parking from 1981 until it was paved over in 2003. This use as a driveway was certainly open and notorious. No testimony was given that anyone else besides the residents of the Walsh Property used the Walsh's driveway or claimed such a right. I find that the Trust has presented sufficient evidence that Walsh adversely possessed the area of the former gravel driveway.

I cannot, however, find that the Trust has established adverse possession of the area of the paved driveway. Though the Walshes and DeLouis testified that the paved driveway was installed in the same location as the gravel driveway, none of them were present at the Walsh Property when the driveway was installed. Walsh also testified that the gravel driveway was straighter than the current paved driveway. The Walshes and DeLouis testified that once the asphalt was laid they did not take any measurements or do anything to verify whether the paved driveway was in a different location than the gravel driveway, closer to the Fitzgibbon Property. I do not credit their testimony as to the location of paved driveway in relation to the gravel driveway. Ms. Fitzgibbon, however, was present and observed the installation of the driveway, which she testified was laid out wider than the edge of the gravel driveway, closer to her property line. She took pictures and measurements of the distance from the northeast corner of her house to the common boundary line and found that, according to the Troupes Plan, and later the Smith Plan, the paved driveway encroached onto her property. Ms. Fitzgibbon attested that the prior gravel driveway was straighter than its present configuration. She stated that the paving of the driveway in 2003 changed the configuration, such that it now curves westward towards the Fitzgibbon Property. I credit Ms. Fitzgibbon's testimony and find that the gravel driveway was widened and moved closer to the Fitzgibbon Property when it was paved. The photographic evidence and testimony shows that pavement laid out in 2003 extended beyond the dimension of the gravel driveway to an orange line spray painted approximately 1.5 feet inside the string guideline on what Walsh believed was the common boundary line.

Although Walsh adversely possessed the area of the gravel driveway, but not any portion widened when it was paved in 2003, there is insufficient evidence in the record to determine the location of the prior gravel drive in relation to the shared boundary line and, whether, according to the Smith Plan, it would encroach on the Fitzgibbon Property. Therefore, I cannot find that the Trust has any title by adverse possession. Because I find that the Carter Plan accurately depicts the location of the boundary line, meaning that neither the driveway nor any other structure encroaches on the Fitzgibbon Property, I need not determine at this time the precise area the Trust claims to have adversely possessed, and will dismiss the adverse possession claim without prejudice. For the same reasons, I will dismiss the Fitzgibbons' trespass-related counterclaims without prejudice.

Finally, it is important to state that this Decision only adjudicates the location of the common boundary line between the Walsh and Fitzgibbon Properties. Because the Trust and the Fitzgibbons are the only parties to this action, I am unable to make findings with respect to the rights of nonparties. This decision is only binding as to the respective rights of the Trust and the Fitzgibbons. Throughout this decision I make no determination as to the rights of any nonparty. Specifically, I make no decision on the location of boundary lines following apportionment for the remaining six lots with frontage on Pond Street.

Conclusion

Judgment shall enter declaring that the common boundary between the Walsh Property and the Fitzgibbon Property is as determined by Carter and shown on the Carter Plan. No determination is made as to the location of any other property lines after proration of the remaining six lots belonging to nonparties to this action. Walsh's adverse possession claim and counts II, III, and IV of the Fitzgibbons' counterclaims are dismissed without prejudice.

Judgment accordingly.

REGINA WALSH SULLIVAN, as Trustee of the WALTER J. WALSH IRREVOCABLE TRUST v. MATTHEW J. FITZGIBBON and CYNTHIA FITZGIBBON.

REGINA WALSH SULLIVAN, as Trustee of the WALTER J. WALSH IRREVOCABLE TRUST v. MATTHEW J. FITZGIBBON and CYNTHIA FITZGIBBON.