Plaintiffs John W. Baker (Baker) and Susan Baker (collectively the Bakers), and defendants Bonnie Hobson (Hobson) and John Hobson, Thomas Watson, and the Watson/Clark's Island Realty Trust (WCIRT) own property on Clark's Island, an approximately 86-acre island in Plymouth Harbor that is part of the Town of Plymouth. Baker has brought this action seeking to establish his right to pass and repass over a right of way on the island using his "Sea Legs" amphibious vehicle. Hobson argues that the right of way at issue has been abandoned and relocated to another pathway, which has actually been used for decades by people on the island instead of the original right of way. Both Baker and the WCIRT assert that the original right of way has not been abandoned. However, if the right of way has been abandoned and relocated, Baker desires it to be widened to twenty feet so that his Sea Legs can gain access, while the WCIRT contends it should be left in its present state because widening the pathway may cause additional erosion to their property. After a trial on all these issues, I find that, based on the conduct of the parties, a portion of the original right of way has been abandoned and relocated to the pathway, which may only be widened to a uniform width of ten feet. Baker, and the other parties to this action, have the right to pass and repass over the relocated right of way to access their properties on the island.

PROCEDURAL HISTORY

The Complaint was filed on November 22, 2013. The Answer of Bonnie Hobson, John Hobson was filed on January 29, 2014. On March 3, 2014, the Amended Complaint was filed. On April 4, 2014, the Second Amended Complaint was filed Nunc Pro Tunc as of March 31, 2014. The Answer of Thomas Watson was filed April 22, 2014. Defendant Watson/Clark's Island Realty Trust's Answer to the Second Amended Complaint was filed on December 14, 2014. Following discovery, a pre-trial conference was held on December 1, 2015.

Plaintiffs' Motion in Limine to Exclude Documents set forth in Defendant, Bonnie Hobson's List of Proposed Exhibits relevant to the Issues of Bad Faith and Claim Preclusion, Memorandum in Support of Plaintiffs' Motion in Limine to Exclude Documents set forth in Defendant, Bonnie Hobson's List of Proposed Exhibits relevant to the Issues of Bad Faith and Claim Preclusion, and Defendant's List of Proposed Exhibits were filed on May 6, 2016. Defendant Trustees of the Watson/Clark's Island Realty Trust's Motion in Limine to Exclude Defendant Hobson's Proposed Bad Faith Documents and Evidence at Trial was filed on May 9, 2016. A hearing on the Motion in Limine to Exclude Documents set forth in Defendant, Bonnie Hobson's List of Proposed Exhibits relevant to the Issues of Bad Faith and Claim Preclusion was held on May 24, 2016, where the Motion in Limine was allowed in part and denied in part. The court stated: "Complaint, counterclaim, amended counterclaim, and judgment in previous Superior Court action may be admitted. Proposed exhibits dated post-judgment will not be admitted. The Court sees these last exhibits as having minimal relevance to this matter but will be decided at trial."

A view of the subject property was held on June 9, 2016. A trial was held on June 13-14, 2016. Exhibits 1-33 were marked. Testimony was heard from John W. Baker, William Watson Taylor, Jr., Karen Crimmins, John M. Watson, David M. Watson, Bonnie Hobson, Thomas Watson, and Joseph Randolph Parker, Jr. On the second day of trial, Defendant Watson/Clark's Island Realty Trust's Motion in Limine to Exclude Proposed Evidence First Disclosed on the First Day of Trial was filed and heard. After consideration the court ordered that "defendant Hobson may elicit testimony from her expert Randolph Parker only on matters already disclosed in expert disclosure in joint pretrial memorandum." The court ordered Bonnie Hobson to file and serve a revised expert disclosure and an opposition to the Motion in Limine and permitted the parties to reserve their right to cross-examine Mr. Parker on his testimony on that day as well as any new testimony. After Mr. Parker's testimony, the trial was suspended. Defendant Bonnie Hobson's Supplemental Expert Disclosure Statement and Opposition of Defendant Bonnie Hobson to Defendant Watson/Clark's Island Realty Trust's Motion in Limine were filed on June 27, 2016. Defendant Watson/Clark's Island Realty Trust's Reply to Defendant Hobson's Opposition to its Motion in Limine to Exclude Proposed Evidence First Disclosed on the First Date of Trial and Plaintiff's Motion to Exclude Evidence and to Limit Testimony of J. Randolph Parker, Jr. were filed on July 11, 2016. A telephone status conference was held on July 11, 2016, where the court allowed the Motion in Limine. On July 13, 2016, counsel reported that they would not undertake cross-examination of defendant Hobson's expert witness Randolph Parker. Evidence was then closed.

Defendant Watson/Clark's Island Realty Trust's Trial Memorandum was filed on August 19, 2016. Defendant Bonnie Hobson's Proposed Findings of Fact, Rulings of Law and Judgment was filed on August 22, 2016. Plaintiffs' Trial Memorandum was filed on August 26, 2016. Defendant Watson/Clark's Island Realty Trust's Reply to Defendant Bonnie H. Hobson's Proposed Findings of Fact, Rulings of Law, and Judgment was filed on September 14, 2016. Closing arguments were heard on September 21, 2016. Upon receipt of the transcripts, this matter was taken under advisement.

FINDINGS OF FACT

Based on the view, the undisputed facts, the exhibits, the testimony at trial, and my assessment of credibility, I make the following findings of fact.

Background of Clark's Island

1. On February 24, 1882, the Plymouth County Superior Court in James M. Watson, et. al. v. Horace H. Watson, et. al., entered a decree (Decree) confirming a warrant and commissioner's report dated November 19, 1881, recorded in the Plymouth County Registry of Deeds (registry) in Book 546, Page 527, and ordering the partition of property located on Clark's Island belonging to Albert M. Watson. The property was divided amongst Albert M. Watson's three sons, James M. Watson, Edward W. Watson, and Albert Mortimer Watson. Exh. 1, ¶ 11; Exh. 6.

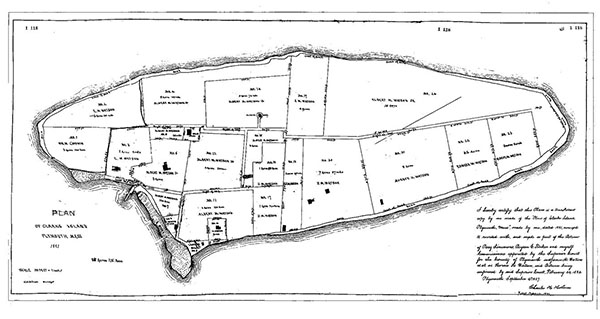

2. As part of and in connection with the Decree, the property involved in the partition, as well as other lots on Clark's Island, were shown on a plan of land entitled "Plan of Clark's Island, Plymouth, Mass." dated 1881 and recorded in the registry on September 1, 1891

at Plan Book 1, Page 118 (1881 Plan), attached here as Exhibit A. The 1881 Plan depicts lots on Clark's Island numbered 1-24. Among the parcels on Clark's Island that were not subject to the Decree was a lot previously conveyed by Edward W. Watson to James Deacon by a deed dated September 10, 1874, and recorded in the registry at Book 410, Page 156 (Deacon Deed), shown as Lot 8 on the 1881 Plan. Exh. 1, ¶ 11; Exhs. 6, 12, 30.

3. The 1881 Plan shows several twenty-foot-wide rights of ways across the island that provide access from landlocked parcels to the shores. The right of way at issue in this case runs from Lot 9, at the southeast corner of the island otherwise known as "the Point", westerly between Lots 7 and 8 to the south and Lot 11 to the north, and ends at the intersection of another right of way running roughly north-south, an intersection known as "Times Square" located where the corners of Lots 6, 7, 11, and 12 adjoin (1881 ROW). Exhs. 11A-D, 12.

4. Lot 8, as shown on the 1881 Plan, is not accurately depicted. The Deacon Deed conveyed two separately described parcels, the first of which makes up Lot 8 as shown on the 1881 Plan. The second parcel is described as "a strip sixteen feet wide along the shore at high water mark northeasterly from said land above described to the point so called, and which shall extend in the same line to low water mark." This strip of land is not shown as part of Lot 8 on the 1881 Plan. This description indicates that Lot 8 and Lot 9 are actually contiguous. The Deacon Deed also references two stone walls separating Lot 8 from the 1881 ROW along its western and northern lot lines. These stone walls no longer exist in that location. Tr. 2:126-132; Exhs. 12, 30.

5. The Decree granted certain easement rights in the rights of way to owners of the parcels subject to the Decree. The Decree stated that the rights of way, as shown on the 1881 Plan, can be used "to pass and repass over the same for any purpose for which highways may be lawfully used." Exh. 1, ¶ 11; Exh. 6.

6. The Decree granted the right to use two wells on Lot 15 and on Lot 11. Exhs. 6, 12.

7. In addition, the Decree granted the right to use Lot 9, or the Point, "as landing places are commonly used and as said landing place and flats have customarily been used", along with the right to wharf or build on it, but limited to structures no more than fifty feet wide. Exhs. 6, 12.

8. Further, the Decree granted the rights to use an old wharf and pier and the "flats contiguous thereto as are not subsequently wharfed in or built over" on Lot 3, and the "old stone wharf" and the "flats contiguous thereto as are not subsequently wharfed in or build over" on Lots 3, 6, and 7. This area, located on the southern side of the island, just south of Lots 7 and 8 and the area depicted as "Marsh" on the 1881 Plan, is also known as "the Cove." Tr. 1:29-30, 222-223; Exhs. 6, 12, 24, 33.

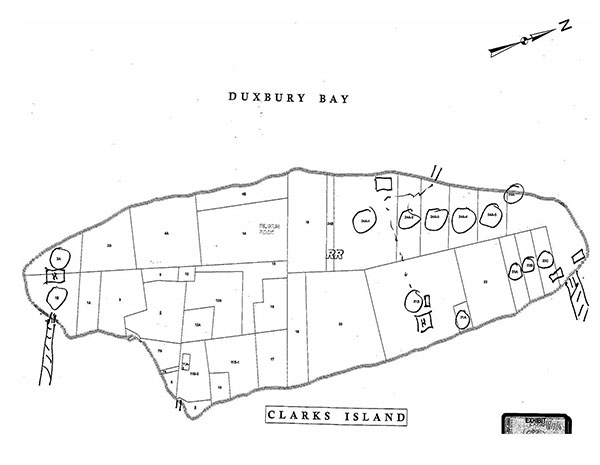

9. The configuration of the lots on Clark's Island has changed since the 1881 Plan, including various lots being subdivided. A Town of Plymouth Assessor's Map dated January 1, 2013, shows the present configuration of the lots (Assessor's Map). The Assessor's Map is attached here as Exhibit B. Exh. 15.

10. Plaintiffs John W. Baker (Baker) and Susan Baker (collectively the Bakers) own several lots on Clark's Island. On the north end of the island, the Bakers own parcels of land shown on the Assessor's Map as Lots 21A, 21B, 23A, 23B, 23C, 24A, 24A-1, 24A-2, 24A-3, 24A-4, and 24A-5. Lots 21A and 21B consist of approximately eight acres and are improved by a residence. Tr. 1:13-14, 16-18; Exh. 1, ¶¶ 1, 5, 7-9; Exhs. 1A, 4-5, 15.

11. The Bakers own other parcels of land on the south end of Clark's Island shown on the Assessor's Map as Lots 1B and 2A. These lots consist of about four acres and are improved by a residence that straddles both lots. Tr. 1:14-15; Exh. 1, ¶ 6; Exhs. 2, 15.

12. Defendant Bonnie Hobson (Hobson) resides at 117 Clifford Road, Plymouth, MA. Hobson is the owner of five parcels of land on Clark's Island shown on the Assessor's Map as Lots 2B, 3, 8, 12A, and 22. Lot 22 is on the north end of the island and is completely surrounded by the Bakers' north end lots. Lots 2B, 3, 8, and 12A are on the south end of the island. Lot 8 is the same Lot 8 conveyed in the 1874 Deacon Deed. It abuts the 1881 ROW at issue. Exh. 1, ¶¶ 2, 10; Exh. 15.

13. Defendants Karen A. Crimmins, John M. Watson, and David M. Watson, are the Trustees of the Watson/Clark's Island Realty Trust (WCIRT), which owns two parcels of land on the south end Clark's Island shown on the Assessor's Map as Lot 9 (the Point) and Lot 11B-1. Exh. 1, ¶ 3, 15.

14. Defendant Thomas C. Watson (Thomas Watson) owns a parcel of land on the south end of Clark's Island shown on the Assessor's Map as Lot 11B-2. Lot 11B-2 abuts the 1881 ROW opposite Lot 8. Thomas Watson previously owned a lot on the north end of the island and Baker owned Lot 11B-2, but they conducted a land swap in which each conveyed their property to the other, leaving Baker with a lot in the north end and Thomas Watson with Lot 11B-2. In conveying Lot 11B-2 to Thomas Watson, Baker reserved for himself a right of first refusal if the property was to be sold. Tr. 1:41-43; Tr. 2:65-66; Exh. 15.

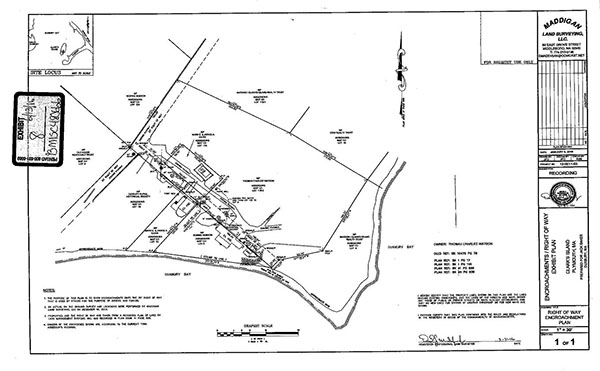

15. In 1998, Hobson entered a verbal agreement with Thomas Watson to purchase a portion of Lot 11B-2, and her intention was to move the home located on Lot 8 onto a portion of Lot 11B-2 at some future date. To facilitate the purchase, a plan was prepared by Land

Management Systems and provided to Hobson by Thomas Watson. The plan depicted the 1881 ROW; Hobson did not mention to Thomas Watson or the surveyors at that time that the 1881 ROW was abandoned or altered. In exchange for the purchase of a portion of Lot 11B-2, Hobson gave Thomas Watson $10,000 and Hobson's mother gave him $10,000. Due to Baker's right of first refusal, Thomas Watson was unable to convey the land to Hobson and the deal fell through. Thomas Watson verbally agreed to pay back the $20,000 to Hobson and her mother, though there was no formal agreement. Thomas Watson began making payments to Hobson's mother, but stopped about five or ten years ago because he no longer had the financial resources to repay Hobson. Hobson has allowed Thomas Watson to live at her property in downtown Plymouth since November, 2015 for $600 per month. Tr. 2:7-9, 28-29, 53, 58-60, 63, 74, 77-81; Exh. 7.

The 1881 ROW

16. The 1881 ROW is not readily accessible. There are obstructions to passage lying within the 1881 ROW along Lot 8 including an old stone wall, well, outhouse, cesspool, overgrown vegetation, and other junk that make it virtually impassible at either end of Lot 8. Mark Quirk and Janice Quirk (Quirks), owners of Lot 7A and 11A, have a stone well, shed, and garden that are also within the 1881 ROW. Except for the items of junk, the other obstructions have existed in their present locations for at least 70 years. View; Tr. 1:23-26, 67-68, 80-81, 132- 133, 136-138, 156, 164, 170, 172-173, 187-188, 191, 193, 219, 227, 239-241, 243, 246-250, 253, 260-263; Tr. 2:11-12, 19, 50-51, 72-73; Exhs. 8, 9A-G, 9H, 20.

17. Hobson is 73 years old and has visited and/or lived on Clark's Island for her entire life. On April 8, 1964, when she was 21 years old, she took title to Lot 8 by deed from her grandmother, Alice Wood who had acquired the property by deed on January 3, 1920. Tr. 1:223- 224, 235; Exh. 13.

18. Shortly after Alice Wood acquired Lot 8 in 1920, Hobson's grandfather had a stone wall erected that wrapped around the easterly and southerly seaward portion of Lot 8, into and across a portion of the 1881 ROW. A survey of the area was performed by the WCIRT in 1991 that shows the remnants of the stone wall as extending into the 1881 ROW. All that remains of the stone wall today is pile of large rocks and boulders that partially block the 1881 ROW. View; Tr. 1:219, 260-262; Exhs. 6, 9A-B, 9D, 29A.

19. The beginning of the 1881 ROW is located below the stone wall and is marked by two iron pipes, one of which is located within a salt marsh and the other of which is completely underwater at high tide. Some of the boulders that compose the former stone wall are also partially underwater at high tide. This has prevented people from walking on the beginning portion of the 1881 ROW. View; Tr. 1:172, 192-194, 218-219, 263-264; Exh. 29.

20. There is an old well with an open pipe next to Lot 8 that is located within the 1881 ROW. The only person known to have used the well was Hobson, and her family who used to store milk bottles in it as a means of refrigeration during Hobson's childhood. Since then, the owners of Lot 8 have maintained a wooden cover over the open well to prevent anything from falling in. View; Tr. 1:133, 248-250, 253-254; Tr. 2:13; Exhs. 8, 9E-H.

21. An outhouse, located directly behind the residence on Lot 8, is also within the 1881 ROW. William Taylor, Jr. (Taylor) owns Lot 6 on the island and testified that he used to spend time with Alice Wood as a child during the 1950s and 1960s. The outhouse was used by the occupants of the Lot 8 residence during this period and Taylor would frequently walk in the 1881 ROW to access the outhouse, as well as empty a chamber pot into the ROW. In the summer of 1968, Taylor stated that the outhouse stopped being used when a cesspool was dug and a toilet was installed in the residence on Lot 8. Since that time, the outhouse has remained unused, but it has remained in the same location it was always in. The location of the cesspool is not readily identifiable on the ground, but it is also within the 1881 ROW. View; Tr. 1:131-133, 156-157, 168, 243, 246, 249; Exh. 9D.

22. The 1881 ROW is presently so overgrown with shrubs and trees, and blocked by structures and other objects, as to render it nearly impassible. Every witness who testified about the overgrowth and obstacles in the 1881 ROW stated that it has always been that way for as far back as any of them can remember. I credit their testimony. View; Tr. 1:135, 163-164, 204, 240, 253; Exhs. 8, 9A, 9B, 9D, 9F, 9G, 11G, 20.

23. The only part of the 1881 ROW that has not always been overgrown lies behind Hobson's residence on Lot 8. This area is approximately 27 feet by 40 feet. Hobson testified, and I find, that it has always been used by the residents of Lot 8 as their backyard where they would socialize and play games such as croquet, badminton, and ping pong. Other witnesses, including Taylor, John M. Watson, and David M. Watson, also acknowledged the area as being used as a backyard for Lot 8, rather than a right of way. View; Tr. 1:157-158, 191, 213, 227, 254; Tr. 2:12- 13; Exh. 8.

24. The Quirks' shed, adjacent to Lot 7, is also located within the 1881 ROW. The current shed was installed by the Quirks within approximately the last five years and is not permanently affixed to the ground, but on cinder blocks. Prior to that, witnesses recalled that there was a metal shed in approximately the same location as the new shed that had been there at least since they were children. View; Tr. 1:79-80, 137-138, 164, 187-188, 247-248; Tr. 2:12-13, 51.

25. Another well with a stone around it is located further up in the 1881 ROW, just before Times Square, adjacent to the Quirks' property at Lot 11A. Hobson testified that she never used the stone well and cannot recall ever seeing anyone drawing water from that well. A garden belonging to the Quirks also lies within the 1881 ROW. View; Tr. 1:80-81, 251-253; Tr. 2:51; Exhs. 8, 12.

26. With the exception of Taylor, all the witnesses who own property on Clark's Island testified, and I find, that they have never known of or seen anyone use the 1881 ROW for access to or from anywhere on the island. Hobson's testimony, which I credit, was that no one has ever asked her to remove anything from the 1881 ROW. Tr. 1:47-49, 154, 168-170, 190-191, 212-213, 227, 232; Tr. 2:19, 24-25, 61-62, 70, 72.

27. Taylor testified that from about 1953 to the mid-1960s when he visited the island, he used the 1881 ROW in order to access the outhouse when he was staying at the house on Lot 8. He testified that at some point after use of the outhouse ceased and he stopped staying at Lot 8, he began walking the 1881 ROW. He stated that he walks on the 1881 ROW during the wintertime when he is on the island alone to exercise his right to go onto the rights of way and uses it to access the Point and the Cove. He testified that the last time he had walked the 1881 ROW was during the winter, a few months prior to trial, when he was aware that this action was pending. Though he acknowledged that the 1881 ROW is overgrown, he stated that he can get through easier during the winter when some of the vegetation has died. I do not credit Taylor's testimony as to his use of the 1881 ROW. Taylor testified that he only walks the 1881 ROW during the winter when he is alone on the island. No other witnesses testified to seeing Taylor walk on the 1881 ROW. I find that he infrequently walks along the 1881 ROW in order to protect his easement rights. He also agreed that a portion of the 1881 ROW is functionally the backyard of Lot 8. View; Tr. 1:134-136, 150, 153-155, 157-158.

28. Baker testified that since he moved onto the island in 1979, he has never seen anyone use the 1881 ROW. When he owned Lot 11B-2, he did not widen or make use of the 1881 ROW. I credit Baker's testimony. Tr. 47-48.

29. David Watson also did work for Baker when Baker owned Lot 11B-2. He stated, and I find, that Baker never sought to clear the 1881 ROW, never suggested he should do that, and no one he knows has ever sought to clear it until now. Tr. 1:215-216.

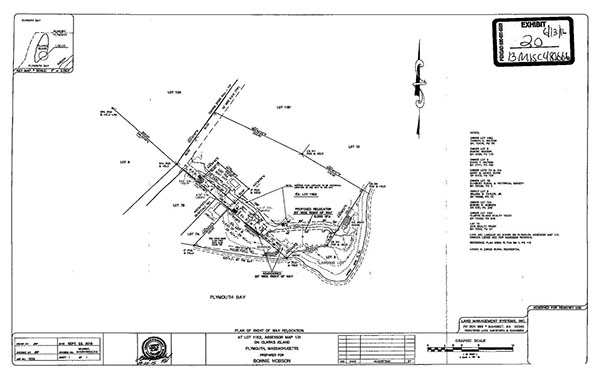

The Path

30. Located adjacent to the 1881 ROW is a pathway that begins near an existing boathouse on Lot 9, with the rest of it on Lot 11B-2, Thomas Watson's property, and Lot 11A, the Quirk's property, and ends at Times Square (the Path). The Path is depicted as "Ex. Path" on a plan attached here as Exhibit C. Starting from Lot 9, the Path is approximately 145-150 feet long, at which point it hits the backyard of Lot 8 and curves northwesterly, then runs roughly parallel to the 1881 ROW for approximately 277.46 feet until it intersects with Times Square. No part of the Path is within the 1881 ROW. The majority of the Path is about 7 to 9 feet wide, with the exception of a few areas: where the Path opens up to Hobson's backyard (an area about 27 feet by 40 feet), in front of Lot 11A (about 10.5 feet wide), and as it approaches the Times Square intersection (about 15 feet wide). Exhs. 8, 9F, 9G, 11F, 11G, 11H, 20; Tr. 1:48; View.

31. Based on testimony at trial, I find that the Path has always been in essentially its present location. Though the Path used to have a fairly consistent width of about 6 or 7 feet, it has become wider in parts over the years to accommodate motorized golf carts and lawnmowers. Tr. 1:148-149, 161, 169, 195-196, 231; Tr. 2:26-27.

32. Taylor testified that the Path has existed for as long as he has been on the island, since 1949, and he has frequently has used the Path to access the Point. He stated that anyone trying to access the Point from the island or coming from the Point onto the island would use the Path. I credit this testimony. Tr. 1:148-149, 152-154.

33. Karen Crimmins (Crimmins), a trustee of the WCIRT, stated that she has always used the Path to access the Point, and never the 1881 ROW, because at all times the 1881 ROW has been obstructed. In fact, Crimmins stated that she did not even know about the 1881 ROW when she was a child on the island because the way was so overgrown. No one has ever prevented her from using the Path. I credit her testimony. Tr. 1:163-165, 169-170.

34. John Watson, a trustee of the WCIRT, testified that he and his family used the Path to access different parts of the island. He stated that while he has walked in the 1881 ROW area, neither he, nor anyone he remembered, has ever used the 1881 ROW for the purpose of a right of way because it had been blocked for his entire life. I credit his testimony. Tr. 1:180-182, 191.

35. David Watson, a trustee of the WCIRT, testified that he and his relatives always used the Path and never the 1881 ROW. The only use he noticed was in the portion of the 1881 ROW directly behind the Hobson residence, which the owners of Lot 8 essentially used as a backyard. I credit his testimony. Tr. 1:212-213.

36. Hobson testified, and I find, that she has known of and used the Path to access Lot 9 for as long as she can remember. She primarily visits the island from March to November, and is consistently on the island every day from June to September when she most frequently uses the Path. She has observed others using the Path as well, including the Quirks, Taylor, and Thomas Watson. No one has ever tried to prohibit or restrict her use of the Path, nor has anyone given her permission to use it, including Baker when he owned Lot 11B-2. Hobson and her husband, John Hobson, maintained the Path by mowing it and cutting down overhanging branches from the vegetation. I find that she never asked anyone permission to maintain it and Thomas Watson never objected to the maintenance. Tr. 1:230-233; Tr. 2:26-27.

37. While Baker did not use the 1881 ROW when he owned Lot 11B-2, I find that he did make use of the existing Path and did not prevent others from using it. Tr. 1:48-52.

38. I find that no one ever sought permission from Thomas Watson to use the Path as it runs across Lot 11B-2, his property, and he never suggested or indicated to anyone using the Path that he did not want it used as a right of way. Tr. 2:77.

The Present Action

39. In April 2012, Baker began purchasing Sea Legs amphibious vehicles to assist him in accessing Clark's Island due to worsening peripheral neuropathy in both legs, which leaves him with no feeling in his feet and a loss of balance. These vehicles can be driven on public roads. Baker uses the Sea Legs to get from this property on the mainland of Plymouth to his properties on Clark's Island. Baker currently owns nine Sea Legs of various styles and sizes. Baker typically uses a Sea Legs that is 8.5 feet wide on the island, but he has a Sea Legs that is 13.5 feet wide that he would like to be able to use as well. View; Tr. 1:28, 82-87, 111-112; Exhs. 10, 11I-L.

40. Currently, there are multiple landings on the island that Baker uses to access his residences. First, there is a ramp for the Sea Legs vehicles on the west side of Clark's Island off Lot 24A-3. From this ramp, Baker can use the Sea Legs to access his lots on the north end of the island and his residence on Lot 21. There is also a pier located off Lot 24A in the north end. In addition, the island can be accessed from the southeastern end where a ramp and pier are also located off Lot 1B. From this ramp, Baker can use the Sea Legs to access his residence on Lots 1B and 2A. These access points are depicted on the version of the Assessor's Map attached here as Exhibit B. Tr. 1:28, 31, 87-88, 91-93, 98-99; Exhs. 15, 21-23.

41. In a prior suit in Plymouth Superior Court between the Bakers, the Hobsons, and Virginia Hutton, Baker claimed an easement by prescription over Hobson's Lot 2B, located between Lot 2A and 4A as shown on the Assessor's Map. It also involved a portion of the right of way on the north end of the island leading to Lot 22, owned by the Hobsons, which they claimed the Bakers were obstructing. Judgment in that case was entered on June 18, 2009. The court enjoined the Bakers from passing over Lot 22 and ordered them to remove encroachments within the right of way on the north end, beginning at Lot 24B. Baker cleared this right of way on the northern end to maintain its 20 foot width. In addition, the judgment granted the Bakers a prescriptive easement over the pathway on Lot 2B "as it existed on February 2, 2009, for reasonable access to and from the 20-foot right-of-way that commences at the northerly end of Lot 4." This easement allows Baker to go from Lot 1B or 2A and pass over Lot 2B to access the 20 foot right of way connecting the north end to the south end of the island. However, Baker cannot travel from the south end to the north end of the island because the prescriptive easement section is not wide enough for the Sea Legs and cannot be widened due to the terms of the Judgment. Tr. 1:31-37, 43-44, 50-51, 54; Exhs. 15, 25-28.

42. Although Baker has the other access points to get on the island, he testified that when there are heavy winds coming west-northwest, the Sea Legs is prevented from accessing the island due to waves causing the bow of the vehicle to rise up and crash down, which can smash the bow causing damage to the front leg of the vehicle. Because of the direction of these winds, Baker desires an access point on the east side of the island. Tr. 1:28, 104-106.

43. Baker testified that he is unable to use the Cove to access the island because floats block his access to the shoreline. He further claims that even if the floats weren't there he would need to drive over beach grass or eelgrass, which, according to him, presents environmental concerns. Tr. 1:30-32, 94-96; Exhs. 12, 24, 33.

44. Baker also considered whether he could access the island from the Point, near a boat house on Lot 9, since the Decree also granted rights to use the area for landing purposes. He testified that he would be able to get the Sea Legs onto the island this way, but it wouldn't be desirable due to outhauls in the area and the rocks on the beach in front of the pathway from the Point to the entrance of the Path. Tr. 1:39-41, 108-109; Exh. 31.

45. Baker testified that the Path is not currently wide enough for the Sea Legs. Aside from the width, he stated that he could not use the Path because there is a "dogleg" in the Path "going directly to the left and then the right again," where it comes up to Hobson's backyard, and to maneuver that Sea Legs would require more than 20 feet. Based on the view and the surveys in evidence of the Path, I do not credit this testimony about the orientation of the Path. View; Tr. 1:122-124; Exh. 20.

46. Having exhausted all other options for points of entry on the east side of the island, Baker desires to use the 1881 ROW. Due to the several obstacles in the 1881 ROW, Baker is currently unable to utilize the Sea Legs to travel over the 1881 ROW. Baker sent a letter to Hobson on or about May 31, 2013, requesting that Hobson remove the encroachments from the 1881 ROW. When she did not remove the obstructions, this suit followed. Exh. 1, ¶ 12.

47. Baker had the area surveyed to determine the location of the 1881 ROW and the Path (2016 Survey). The 2016 Survey revealed that the obstructions, discussed above, to the 1881 ROW were not on Hobson's property, but on Thomas Watson's Lot 11B-2. The 2016 Survey is consistent with my observations on the view. The 2016 Survey is attached here as Exhibit D. View; Exh. 1, ¶ 12, Exh. 8; Tr. 1:20, 23-26, 74, 79-80.

48. Thomas Watson testified that he had no objection to the use of the Path on his property. If the right of way is relocated, it is his preference, due to the risk of erosion, that the width be limited to the existing Path and not widened to 20 feet, or widened only the minimum width needed to accommodate Baker's Sea Legs. Hobson also approached him about granting her an easement to continue to use the Path on Lot 11B-2 as the right of way. Thomas Watson expressed that, if necessary, he would grant such an express easement and Hobson had not indicated that she would forgive the debt he owed in consideration of granting the easement. Tr. 1:171, 212; Tr. 2: 74-76, 79, 86-87; Exh. 20.

49. The trustees of the WCIRT stated that they never intended to abandon the 1881 ROW and want it to be reopened. They were concerned that if the 1881 ROW were relocated to the Path and widened to 20 feet, it would cause further erosion to the Lot 9 WCIRT property. The trustees testified that they were not opposed to relocating the 1881 ROW to the Path, if the Path were not widened and left as is. Tr. 1:170-171, 175-176, 178-179, 186, 202, 210-212.

DISCUSSION

Baker seeks declaratory relief under G.L. c. 231A as to his rights to utilize the 1881 ROW. A party seeking a declaratory judgment must "set forth a real dispute caused by the assertion by one party of a legal relation or status or right in which he has a definite interest and the denial of such assertion by the other party, where the circumstances . . . indicate that, unless a determination is had, subsequent litigation as to the identical subject matter will ensue." Hogan v. Hogan, 320 Mass. 658 , 662 (1947). "The actual controversy' requirement of G. L. c. 231A, § 1, is to be liberally construed." Boston v. Keene Corp., 406 Mass. 301 , 304 (1989), citing Massachusetts Ass'n of Independent Ins. Agents & Brokers, Inc. v. Commissioner of Ins., 373 Mass. 290 , 293 (1977). "[A]n express purpose of declaratory judgment is to afford relief from

uncertainty and insecurity with respect to rights, duties, status and other legal relations.'" Keene Corp., 406 Mass. at 304-305, quoting G. L. c. 231A, § 9. In this action, an actual controversy exists between the parties regarding and relating to their legal rights and duties with respect to the 1881 ROW over Lot 11B-2.

Baker argues that he has a general right of way over the 1881 ROW as shown on the 1881 Plan and, more precisely, on the 2016 Survey. He asserts that if the 1881 ROW was abandoned, then it should be relocated to the Path, which should be widened to 20 feet along its entire length. Hobson argues that the 1881 ROW has been abandoned and the Path has always been used in lieu of the 1881 ROW, and, thus, the way should be relocated to where the Path presently exists on the ground. The WCIRT agrees with Baker in that it contends that 1881 ROW was never abandoned. However, unlike Baker, the WCIRT opposes the relocation of the 1881 ROW to the Path if it entails widening it to 20 feet due to concerns about erosion on Lot 9. These arguments are examined in turn below.

Affirmative Defenses

In her Answer and the pre-trial memorandum, Hobson raises two affirmative defenses: laches and claim preclusion. Though not argued at trial, closing arguments, or discussed in Hobson's post-trial filings, with a view that these affirmative defenses are still nonetheless live, I address them here before discussing the merits.

Laches is an unjustified, unreasonable, and prejudicial delay in raising a claim. Laches is not mere delay, but delay that works disadvantage to another. "[L]aches does not operate to bar a claim simply because the events which established rights in the plaintiff occurred long ago." West Broadway Task Force v. Boston Hous. Auth., 414 Mass. 394 , 400 (1993). The burden of proof is on the defendant to show prejudice or disadvantage to sustain a defense of laches. Moseley v. Briggs Realty Co., 320 Mass. 278 , 283 (1946). This burden involves showing that the plaintiff had knowledge of the wrong committed, because there can be no laches where there is no knowledge and no refusal to embrace an opportunity to ascertain facts. See G.E.B. v. S.R.W., 422 Mass. 158 , 166 (1996); Stewart v. Finkelstone, 206 Mass. 28 , 36 (1910); Colony of Wellfleet, Inc. v. Harris, 71 Mass. App. Ct. 522 , 531 (2008).

Hobson has offered no evidence to establish that Baker knew for a significant amount of time that Hobson deemed the 1881 ROW to be abandoned or relocated. Hobson stated that the issue regarding use of the 1881 ROW had never been raised before this case and it had never occurred to her that there was a controversy over whether it had been abandoned. It was only around 2012, when Baker's health began to deteriorate and he sought to use the 1881 ROW for his Sea Legs, that Hobson first claimed the right of way had been abandoned. Nor does Hobson offer evidence that any alleged delay by Baker was unreasonable or caused her to be disadvantaged. Hobson having offered no evidence of delay or prejudice, Baker's claims are not barred by laches.

The doctrine of claim preclusion is also inapplicable. Claim preclusion, also known as res judicata, prohibits the maintenance of an action based on the same claim that was the subject of an earlier action between the same parties or their privies. Heacock v. Heacock, 402 Mass. 21 , 23 n.2 (1988). The three elements of claim preclusion are: (1) identity or privity of the parties to the present and prior actions, (2) identity of the cause of action, and (3) prior final judgment on the merits. See Tuper v. North Adams Ambulance Serv., Inc., 428 Mass. 132 , 134 (1998); Kobrin v. Board of Registration in Med., 444 Mass. 837 , 843 (2005); Gates v. Reilly, 453 Mass. 460 , 464-

465 (2009). Because this is an affirmative defense, Hobson bears the burden of proving all facts necessary to support these elements. Carpenter v. Carpenter, 73 Mass. App. Ct. 732 , 738 (2009).

Hobson is unable to prove these elements. In the prior suit in Plymouth Superior Court, the Bakers sued the Hobsons and Virginia Hutton over rights of way on the island. The issues raised by Baker in this action were not actually litigated between the parties in the earlier case. The locations of the properties in dispute were different in the Plymouth Superior Court case; that case pertained to Baker's claim of an easement by prescription over Hobson's Lot 2B, located between Lot 2A and Lot 4A, and Hobson's claim of interference with the right of way on the north end of the island leading to her Lot 22. In this action, Baker seeks a declaratory judgment as to his rights to utilize the 1881 ROW along Lot 8 to the Point. At the time of the prior litigation, Baker was not in need of the Sea Legs and had no reason to utilize the 1881 ROW. The issue of his right to use the 1881 ROW only arose around 2012, when Baker purchased the Sea Legs and began looking for alternative ways to access the island when there are heavy west-northwest winds. This was never a dispute in the Plymouth Superior Court case. Though this lawsuit may be a further dispute between the same parties, the location of the disputed right of way is on an entirely different part of the island. Moreover, there are other parties in this case who have an interest in the subject of the litigation, Thomas Watson and the WCIRT, that were not parties to the prior suit between the Bakers and the Hobsons. Baker's claims are not barred by claim preclusion.

Abandonment of the 1881 ROW

An easement may be terminated in several ways, including by abandonment. Parlante v. Brooks, 363 Mass. 879 , 880 (1973); Restatement (First) of Property § 504; Restatement (Third) of Property (Servitudes) § 7.4. The two elements necessary to establish abandonment of an easement are the cessation of use and acts indicating an intention never again to make use of the easement. See Parlante, 363 Mass. at 880; Sindler v. William M. Bailey Co., 348 Mass. 589 , 592-593 (1965). Nonuse alone, however, no matter how long continued, does not terminate the easement. See Patterson v. Paul, 448 Mass. 658 , 668 (2007); Lasell College v. Leonard, 32 Mass. App. Ct. 383 , 390 (1992) (nonuse of strip for years not enough to show abandonment); Lemieux v. Rex Leather Finishing Corp., 7 Mass. App. Ct. 417 , 419, 421 (1979) (fact that recorded right of way had been used infrequently for nearly 70 years was not in itself sufficient to extinguish easement). The nonuse must be coupled with an intent to abandon by acts of the dominant estate manifesting "a present intent to relinquish the easement." Willets v. Langhaar, 212 Mass. 573 , 575 (1912); see also First Nat'l Bank of Boston v. Konner, 373 Mass. 463 , 466 (1977) ("the rights of a dominant owner will not be extinguished under the theory of abandonment unless there is nonuser coupled with an intent to abandon").

Particular acts by the owner of the dominant estate may indicate an intention to abandon the easement. See Lasell College, 32 Mass. App. Ct. at 390-391 (landowner's construction of fence separating his property from way established intentional surrender of right to use way); cf. O'Shea v. Mark E. Kelley Co., 273 Mass. 164 , 170 (1930) (easement holder's erection of fence obstructing part of way did not show abandonment of rest of way). "Physical obstructions on the servient tenement, rendering user of the easement impossible and sufficient in themselves to explain the nonuser, combined with [a] great length of time during which no objection [is] made to their continuance nor effort made to remove them, are sufficient to raise the presumption that the right has been abandoned and has now ceased to exist." Lund v. Cox, 281 Mass. 484 , 492-493 (1933) (finding the length of time relevant because the longer the time that a use inconsistent with an easement persists without objection by others with rights in the easement, the strong the evidence of abandonment). Abandonment can also be shown by "[a]ny deliberate conduct on the part of the dominant owner inconsistent with the continued existence of the easement." Proulx v. D'Urso, 60 Mass. App. Ct. 701 , 704 n. 2 (2004). At the very least, in order to show that an easement has been abandoned it is necessary to show "acts by the owner of the dominant estate conclusively and unequivocally manifesting either a present intent to relinquish the easement or a purpose inconsistent with its further existence." Dubinsky v. Cama, 261 Mass. 47 , 57 (1927), citing Willets, 212 Mass. at 575. "Abandonment can be shown by acts indicating an intention never again to make use of the easement in question.'" Parlante, 363 Mass. at 880, quoting Sindler, 348 Mass. at 592. The burden of proving abandonment of an easement rests on the party asserting it, in this case Hobson. See Carlson v. Fontanella, 74 Mass. App. Ct. 155 , 158 (2009).

The only easement holders who are subject to this claim that the 1881 ROW has been abandoned are the Bakers, Watson, and the WCIRT. The facts in this case support a finding that the 1881 ROW was abandoned by the Bakers, Watson, the WCIRT, and their predecessors in title. Nonuse is easily established from the uncontested testimony that the 1881 ROW was never actually used as a right of way. It is plain that the use of such a right of way was rendered impossible by the existence of the outhouse, well, shed, overgrowth of vegetation, and other obstacles placed in the 1881 ROW. Hobson has also established, through ample evidence, the easement holders' intent to abandon the 1881 ROW. With the exception of Taylor, who is not a party, all the witnesses who own property on Clark's Island testified that they have never used, known of, or seen anyone use the 1881 ROW for access to or from anywhere on Clark's Island.

The Bakers, Thomas Watson, the WCIRT, and their predecessors in title have stood by while the 1881 ROW has been essentially confined to the use of the owners of Lot 8 for their backyard and Lot 7 for their garden and shed. Moreover, there is evidence that for at least the last 70 years, the owners and inhabitants of Clark's Island have exclusively used the Path as a right of way and not the 1881 ROW. The Path has always been essentially in its existing location that entire time, approximately parallel to the 1881 ROW, except that it has become wider in certain sections over the years as its use has changed to accommodate golf carts and lawn tractors as well as pedestrian use. Though the owners of Lot 11B-2 never objected to use of the Path across their property, there is no evidence that anyone ever asked for or was granted permission by the owners to use the Path. The consistent testimony at trial was that no permission was ever sought or granted. The evidence of the parties' nonuse of the 1881 ROW, coupled with the acquiescence of all parties over a long period of time in the use of the Path rather than the 1881 ROW, is sufficient to manifest an intent to relinquish rights in the 1881 ROW.

Taylor testified that he used the 1881 ROW from about 1953 to the mid-1960s in order to access the outhouse when he was visiting and staying at the house on Lot 8, and that he walks on the 1881 ROW during the wintertime when he is alone on the island and the overgrown vegetation has died, making it easier to get through. Taylor said that he does this to exercise his right to go onto the rights of way. Taylor's use of the 1881 ROW, when he stayed at Lot 8 and utilized the outhouse, does not consist of using the area as a right of way. Walking to and from the residence on Lot 8 to use the outhouse or emptying the chamber pot is not making use of the area as a means of access. Further, Taylor testified that he only walks the 1881 ROW during the winter when he is alone on the island. No other witnesses testified to seeing Taylor walk on the 1881 ROW. Taylor is not a party, and his testimony is insufficient evidence to rebut a finding that the 1881 ROW was abandoned by the Bakers, Watson, and the WCIRT, and their predecessors.

Apart from Taylor, the record contains no evidence of anyone specifically traveling the 1881 ROW during Hobson's lifetime, about 70 years. There is ample evidence of obstructions to passage lying within the 1881 ROW along Lots 7 and 8 including an old stone wall, two wells, outhouse, cesspool, overgrown vegetation, shed, garden, and other junk. Except for the items of junk, the other obstructions have existed in their present locations for decades. Hobson testified that no one has ever asked her or her predecessors to remove anything from the 1881 ROW because it was preventing them from using it as a means of access. Baker's written request to Hobson in 2013, which triggered this lawsuit, was the first time anyone has mentioned clearing the 1881 ROW.

Based on the foregoing, I find that the 1881 ROW was abandoned from the Point up and along the section of the 1881 ROW abutting Lot 8. Because not all parties owning property abutting the 1881 ROW were parties to this case, such as the Quirks (owners of Lots 7A and 11A) and the Duxbury Rural Historical Society (owner of Lot 7B), I lack the authority to declare the 1881 ROW abandoned along the portions of the ROW abutting those lots.

Relocation of the 1881 ROW

Hobson also contends that the original 1881 ROW was implicitly relocated based on the history of the exclusive use of the Path. In general, the owner of a servient estate may not unilaterally alter or move a dominant owner's easement actually located on the ground without seeking a declaration from the court. See M.P.M. Builders, LLC v. Dwyer, 442 Mass. 87 , 93 (2004). "However, the original easement may be deemed relocated when the conduct of the parties is such as to permit a conclusion that a different easement had been substituted for the way mentioned in the deeds' because the evidence reflects a tacit understanding or an implied agreement,' manifested by the dominant owner's acquiescence' in the use of the different easement in lieu of the original for a number of years." Proulx, 60 Mass. App. Ct. at 705, quoting Anderson v. DeVries, 326 Mass. 127 , 132 (1950); see also Desotell v. Szczygiel, 338 Mass. 153 , 158 (1958) (involving acquiescence in and use of relocated way for only six years); Davis v. Sikes, 254 Mass. 540 , 546547 (1926). The intentions manifested by both the dominant and servient estate owners' conduct are central to a claim that an easement has been relocated. Xarras v. Whitney, 19 LCR 564 , 570-572 (2011); see Carlson, 74 Mass. App. Ct. at 159 ("One does not ordinarily maintain an area as a lawn with the intention of using it, and allowing others to use it, as a road."); Proulx, 60 Mass. App. Ct. at 704 n. 2; Scioletti v. Thomas, 16 LCR 782 , 789-790 (2008) (prior use by predecessors and the acquiescence in that use combine to establish that easement was relocated); Duey v. Trudel, 18 LCR 494 , 495-496 (2010) (subsequent conduct of the parties demonstrates whether there was intent to relocate easement). The doctrine that consent of a party to an easement to a change in the location thereof may be inferred from his acts and conductin other words, such consent may be established by acquiescence or estoppelis supported by many rulings. Desotell, 338 Mass. at 158; Alvord v. Bicknell, 280 Mass. 567 , 572 (1932); Carlson, 74 Mass. App. Ct. at 159; Proulx, 60 Mass. App. Ct. at 705; Lasell College, 32 Mass. App. Ct. at 390.

The Appeals Court's decision in Proulx is instructive. In Proulx, the question was whether the actions of the parties subject to and benefiting from the easement manifested an intent to abandon and change the location of that deeded easement. Proulx, 60 Mass. App. Ct. at 701-703. The servient owner had blockaded and degraded, to a state of impassibility, the original easement despite the dominant owner's knowledge of his right to pass and repass over that area. Id. at 705. The dominant estate owner also further obstructed the original easement, actively improved the alternative right of way for his own benefit, and used the alternate way as the exclusive access to and from his property for a decade. Id. The Appeals Court found that the trial judge did not err in finding that the dominant estate owner's actions "acquiesced in" and "accepted" the change of location of the easement. Id.

Likewise, the dominant estate holders that are parties in this action have engaged in conduct inconsistent with the exercise of their right to use the 1881 ROW and, instead, have taken affirmative steps in the relocation process. As previously stated, the 1881 ROW has not been used as an access route for 70 years at a minimum. Rather, the owners of Lot 8 have appropriated a portion of the 1881 ROW as their backyard where Hobson testified they would socialize and play games such as croquet, badminton, and ping pong. The owners of Lot 8 placed other obstructions in the area such as an outhouse, well, and stone wall. A garden and shed belonging to the Quirks have been placed within the 1881 ROW as well. Neither the servient estate owner, Thomas Watson, nor the Bakers, WCIRT or any other property owner with easement rights pursuant to the Decree ever requested removal of these obstructions from the 1881 ROW. The testimony at trial overwhelming indicated that the Path has been used for decades as a substitute right of way to the 1881 ROW. There are several other paths on the island, not part of the original right of ways shown on the 1881 Plan, which have commonly been used by residents and visitors, but the Path is the only one of these that has always been used as an alternative to the 1881 ROW. When the Path began being utilized as the substituted way of access, the parties acquiesced to the use of this new pathway and there have been no objections until now. As in Proulx, the alternative right of way was improved by the dominant estate owners for their own benefit. While the vegetation within the 1881 ROW has become so overgrown it is practically impassible, the Path was regularly maintained by the Hobsons. All parties, as shown by their conduct, acquiesced in the relocation of the 1881 ROW to the Path.

The parties, by their conduct, also impliedly agreed to the location and width of the Path. Hobson testified that when her and her husband maintained the Path, they merely mowed the grass and cut back any overhanging vegetation. No one has ever attempted to widen it further, nor requested that Hobson cut back the vegetation to make the Path wider. The majority of the Path is about 7 to 9 feet wide, with the exception of a few areas: where the Path opens up to Hobson's backyard (an area about 27 feet by 40 feet), in front of Lot 11A (about 10.5 feet wide), and as it approaches the Times Square intersection (about 15 feet wide). By never clearing the Path to have a 20 foot width, like the 1881 ROW, the parties had implicitly come to an understanding that the Path would be narrower than the original easement. "These acts warrant the inference that [the] parties understood and mutually agreed that the way should be located on the surface of the ground at that place." Dunham v. Dodge, 235 Mass. 367 , 371 (1920). There is no evidence to support the notion that the parties intended that the Path be widened to 20 feet; the evidence is that they have intended the relocated ROW to be more or less as wide as it is currently on the ground. In the interest of consistency, because the Path currently varies in width, and based on the situation of parties, character and configuration of land, and purposes for which it is used, the Path over Lot 11B-2 shall be cleared to have a uniform width of ten feet, except where it is currently wider.

Not all parties with an interest in the 1881 ROW at issue are parties to this case. As this court is unable to make findings with respect to the rights of nonparties, this decision is only binding as to the respective rights of the Bakers, the Hobsons, Thomas Watson, and the WCIRT. Throughout this decision, I make no determination as to the rights of any nonparty. Specifically, I make no decision on whether the remainder of the 1881 ROW north of Lot 8, adjacent to the Quirks' property and Duxbury Rural History Society's property, has been abandoned and relocated to where it crosses over Lot 11A.

Prescriptive Easement over the Path

Hobson also argues, in the alternative, that she and the other residents of the island who use the Point to access their properties have acquired an easement by prescription to continue to use the Path by virtue of their adverse use. To establish a prescriptive easement, a party must prove open, notorious, adverse, and continuous or uninterrupted use of the servient estate for a period of no less than twenty years. G.L. c. 187, § 2; Ryan v. Stavros, 348 Mass. 251 , 263 (1964); Houghton v. Johnson, 71 Mass. App. Ct. 825 , 835 (2008); Long v. Woods, 22 LCR 416 , 420 (2014). Whether the elements of a claim for a prescriptive easement have been satisfied is a factual question, and the party who claims a prescriptive easementhere, Hobsonbears the burden on every element. Denardo v. Stanton, 74 Mass. App. Ct. 358 , 363 (2009); Boothroyd v. Bogartz, 68 Mass. App. Ct. 40 , 44 (2007). These elements are discussed in turn.

The purpose of the requirement of open and notorious use is to ensure that the true owner has notice of a claim of right being made over his property and to give the true owner a "fair chance" to protect their property interests. Foot v. Bauman, 333 Mass. 214 , 218 (1955); see Lawrence v. Town of Concord, 439 Mass. 416 , 421 (2003). When the true owner has actual knowledge of a use being made under a claim of right, the open and notorious element will be satisfied. White v. Hartigan, 464 Mass. 400 , 417 (2013). The use of the Path was clearly open and notorious given that Thomas Watson testified he was aware that people on the island were using the Path over his property and had been doing so even before he owned Lot 11B-2. To be adverse, the use must be made under a claim of right and the true owner must not have given permission for or consented to the use. Id. at 418. Permission is not the same as acquiescence. Houghton, 71 Mass. App. Ct. at 836. While Thomas Watson acquiesced and did not object to the use of the Path, he stated that no one on the island sought out his permission and he never gave anyone permission to use it. His testimony is bolstered by testimony from the other witnesses that they never asked or were granted express or implied permission to use the Path.

The findings of fact demonstrate that the adverse, open and notorious use of the Path has been continuous for no less than twenty years. G.L. c. 187, § 2; Ryan, 348 Mass. at 263. Though the Path is used more frequently during the warmer months when more families are on Clark's Island, the use over the years has been regular and sufficiently pervasive to be continuous. See Mahoney v. Heebner, 343 Mass. 770 , 770 (1961) (seasonal absence does not prevent a finding of continuous use); Kershaw v. Zecchini, 342 Mass. 318 , 320-321 (1961) (finding continuous use in an adverse possession case where a circus performer had marked a boundary, cleared brush, and periodically used the property for exercises and stunts); Stagman v. Kyhos, 19 Mass. App. Ct. 590 , 593 (1985) (noting pattern of regular use on weekends). Families on the island consistently use the Path to go to and from the Point to access their properties. This is exactly the kind of use that would put the owner of the servient estate on notice sufficient to oblige them to take action before the twenty-year period ran. Because neither Thomas Watson, nor his predecessors, took any action in the requisite time period, the parties to this action, in the alternative, acquired an easement by prescription to continue to use the Path in its present state. [Note 1]

Use of the Path

Having determined that the 1881 ROW is relocated to the site of the Path, Hobson argues that the nature and extent of the easement does not allow for the use of Baker's Sea Legs. When determining the extent of an easement, courts look to the intention of the parties regarding the creation of the easement or right of way, determined from the language of the instruments when read in the light of the circumstances attending their execution, the physical condition of the premises, and the knowledge which the parties had or which they are chargeable to determine the existence and attributes of a right of way. Martin v. Simmons Properties, LLC, 467 Mass. 1 , 14 (2014). Courts have held that "an easement granted in general terms is not necessarily limited to the uses made of the dominant estate at the time of the creation of the easement and is available for all reasonable uses to which the dominant estate may thereafter be devoted." Marden v.

Mallard Decoy Club, Inc., 361 Mass. 105 , 107 (1972).

Because the 1881 ROW has been relocated, the purposes of the original easement can be imputed to the Path. The purpose for which the easement was created is plain and unambiguous: those subject to the Decree have the right to use the 1881 ROW "to pass and repass over the same for any purpose for which highways may be lawfully used." While it is clear that Sea Legs amphibious vehicles were not in existence in 1882 when the Decree was entered, that does not limit the use of the ways to means of highway transportation as they existed at that time. See Hodgkins v. Bianchini, 323 Mass. 169 , 172 (1948) (use of way not limited to horse drawn vehicles, but included motor vehicles); Copp v. Foster, 345 Mass. 777 , 777 (1963) (finding original way, though created in 1900 for teams, construed to include right of way for motor vehicles). Modern vehicles, such as golf carts and lawn mowers, currently travel along the Path to and from the Point. Baker testified that he is permitted to drive his Sea Legs on roadways in Massachusetts. As such, Baker's Sea Legs amphibious vehicle would be no different than the other vehicles that are permitted to utilize the Path. This use is consistent with the purpose of the 1881 ROW as stated in the Decree. Though Baker may not be able to effectively maneuver his wider Sea Legs down the Path, to the extent that his slighter vehicles can fit, he has the right to use the Sea Legs on the Path.

CONCLUSION

In view of the foregoing, judgment shall enter declaring that a portion of the 1881 ROW, from the Point and along Lot 8, has been abandoned and relocated to the Path, as it runs on Lot 11B-2 to Lot 9, which shall have a uniform width of ten feet, except where already wider. No determination is made as to whether the remainder of the 1881 ROW, adjacent to property belonging to the Quirks and Duxbury Rural Historical Society, was abandoned or relocated to the Path as it runs across those properties. In the alternative, the parties to this action have a prescriptive easement to travel over the Path for ingress and egress to their properties. Baker may use his Sea Legs on the Path to access his property and to travel to and from the Point.

Judgment accordingly.

JOHN W. BAKER and SUSAN BAKER v. BONNIE HOBSON, JOHN HOBSON, DAVID M. WATSON, KAREN A. CRIMMINS, and JOHN M. WATSON, Trustees of WATSON/CLARK'S ISLAND REALTY TRUST, and THOMAS C. WATSON.

JOHN W. BAKER and SUSAN BAKER v. BONNIE HOBSON, JOHN HOBSON, DAVID M. WATSON, KAREN A. CRIMMINS, and JOHN M. WATSON, Trustees of WATSON/CLARK'S ISLAND REALTY TRUST, and THOMAS C. WATSON.