Plaintiff Katie L. Leahey claims ownership of a portion of a "paper street" in the town of Blackstone, and claims to have extinguished the rights of several of the other property owners along this private way. The plaintiff owns three contiguous lots, two of which abut this paper street, and the defendants likewise each own at least one lot along the paper street's length. Leahey argues that she owns a portion of this way pursuant to G. L. c. 183, § 58, and that actions of her predecessors in title to obstruct the way have extinguished easements held by the defendants over the portion that she owns. The defendants claim in response that their respective easements were never extinguished or abandoned, and that even if their easements have been lost, they have been since re-established by prescriptive use; they also allege in the alternative that the paper street is a public way owned by the town of Blackstone.

Following a view on March 29, 2017, the case was tried before me on March 30, 2017, with testimony from five fact witnesses. Following the submission of post-trial requests for findings of fact and rulings of law, and closing arguments held before me on October 17, 2017, I took the case under advisement. For the reasons stated below, I find and rule that the plaintiff has failed to prove her "try title" claims or her claims for extinguishment by prescription or by abandonment; her claim for an easement by estoppel has been established by stipulation of the parties; I also find and rule that the defendants have failed to prove their counterclaims for declaratory judgment, or easement by prescription or implication, or their cross-claim for declaratory judgment against the town of Blackstone, but based on the parties' stipulation, the defendants have established an easement by estoppel, which has not been extinguished by prescription, abandonment or otherwise.

FACTS

Based on the facts stipulated by the parties, the documentary and testimonial evidence admitted at trial, and my assessment as the trier of fact of the credibility, weight, and inferences reasonably to be drawn from the evidence admitted at trial, I make factual findings as follows:

The Parties and Properties

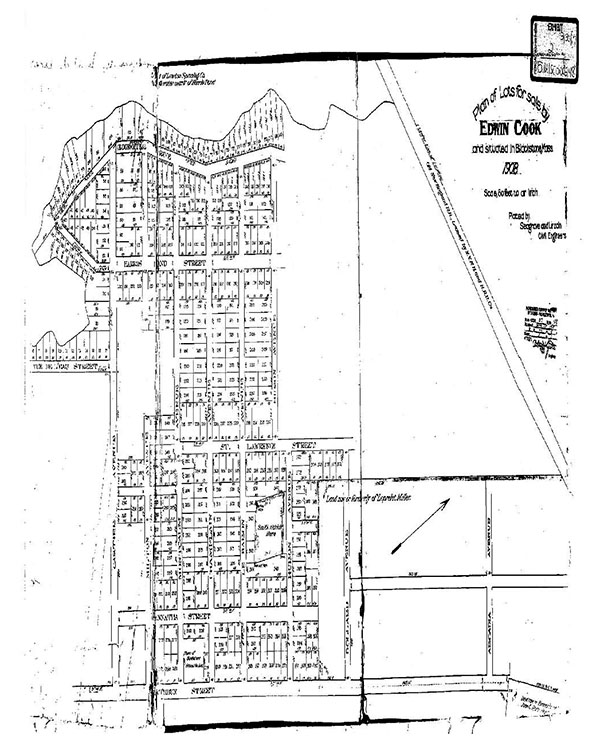

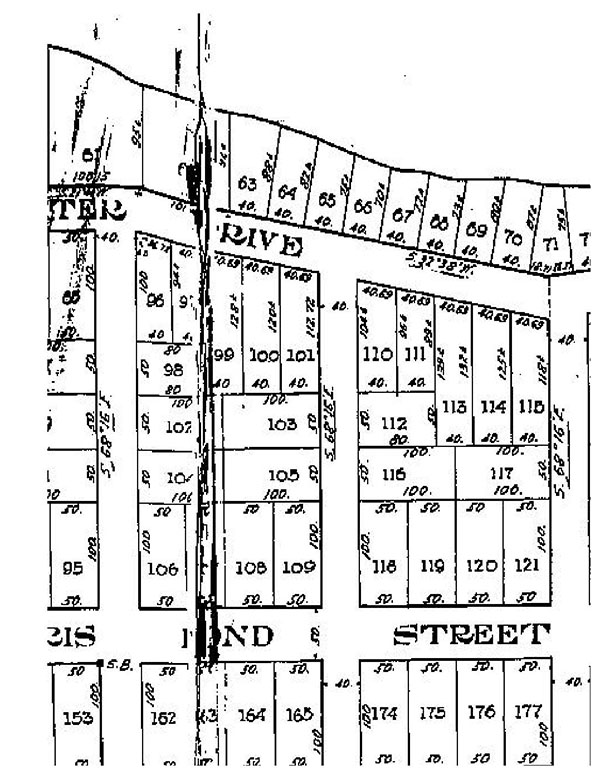

1. All parties in this action own lots that abut a paper street depicted on a plan of land entitled "Plan of Land of lots for sale by Edwin Cook, and situated in Blackstone Mass.," dated 1908, and recorded in the Worcester County Registry of Deeds in Plan Book 27, Plan 58 (the "Plan"). [Note 1] On the plan, this paper street (the "Right of Way") is depicted as the portion of Montcalm Avenue that extends westerly from Harris Pond Street to Edgewater Drive. While the section of Montcalm Avenue depicted on the plan as being to the east of Harris Pond Street is a public way that does indeed exist on the ground, the portion depicted as extending to the west of Harris Pond Street is not a public way, and was never constructed, except for some rough grading and incomplete construction described below. See Appendix A (containing the Plan in full, as taken from Exh. 2); Appendix B (containing an enlarged view of the plaintiff's and defendants' lots).

2. The plaintiff Katie Leahey owns a parcel of land in Blackstone known as 110 Harris Pond Street. Claire Trottier conveyed this property to the plaintiff through a deed dated July 11, 2013, and recorded in the Registry in Book 51456, Page 259. This deed conveyed Lots 116, 118, and 119 as shown on the Plan. Lots 116 and 118 abut the northeastern border of the Right of Way.

3. Federal National Mortgage Association conveyed Lots 110, 111, and 112 as shown on the Plan to defendant Koreen Overt by deed dated July 9, 2012, and recorded in the Registry at Book 49366, Page 351. Lots 110 and 112 abut the northwestern border of the Right of Way.

4. Peter Masson conveyed Lots 99, 100, 101, and 103 to defendants Paul Jean, Laval Jean, and Pauline Jean by deed dated January 30, 1996, and recorded in the Registry in Book 17642, Page 368. There was presumably at least one subsequent intervening transaction not included in the record by which only Laval and Pauline Jean acquired ownership of Lots 99, 100, and 101; Laval Jean and Pauline Jean then conveyed Lots 99, 100, and 101 again to Laval Jean, Pauline Jean, and Paul Jean by deed dated June 10, 2011, and recorded in the Registry in Book 47636, Page 148. Lots 101 and 103 abut the southwestern border of the Right of Way.

5. David H. Lillian conveyed Lots 105, 108, and 109 to Monique Jean by deed dated February 23, 1978, and recorded in the Registry in Book 6403, Page 184. Lots 105 and 109 abut the southeastern border of the Right of Way.

6. Alma B. Sutton conveyed Lot 102 to Laval and Pauline Jean by deed dated June 16, 1960, and recorded in the Registry in Book 4134, Page 192. This lot does not abut the Right of Way, but is contiguous with Lot 103, which does.

The Right of Way

7. Alfred Trottier ("Trottier"), who was born in 1943, lived at the plaintiff's current property, 110 Harris Pond Street (comprised of Lots 116, 118, and 119), with his parents from 1952 until 1964. He was on active duty in the Navy from 1964 until 1966, after which he moved out of 110 Harris Pond Street. His parents continued to live at that address until 2011; during this time, Trottier visited 110 Harris Pond Street approximately once per week. [Note 2] His sister, Monique Boyajian ("Boyajian"), lived at the property from 1952 until 1977, and after that time visited approximately twice per week. [Note 3]

8. The portion of the Right of Way that abuts 110 Harris Pond Street (the "eastern section") appears to have been rough-graded at some point, but has never been paved. [Note 4] Since at least the early 1970s, this portion of the Right of Way has appeared worn and only sparsely covered with grass. [Note 5] Up until 1996, on holidays, a small number of cars belonging to visitors would park on the right side of this area abutting the side of the front yard of 110 Harris Pond Street. [Note 6] Through 1996, the Right of Way was passable by vehicles along the entire length of the Trottiers' property at 110 Harris Pond Street; one would thus have been able to turn off of Harris Pond Street and drive across the Right of Way at least as far as Lot 105. [Note 7]

9. As early as the 1970s, there was a berm of small stones along the south side of the eastern section of the Right of Way; this berm was approximately located where the Right of Way abuts Lot 109, on the opposite side of the Right of Way from the plaintiff's property. [Note 8] This berm was present through the 1990s. [Note 9] It is unclear whether these stones were located on Monique Jean's lot, or in the Right of Way itself. [Note 10] This berm is no longer present.

10. From at least 1952 until 1996, the portion of the Right of Way just beyond the western edge of Lot 116 (the "central section") was wooded, with some brush coverage. [Note 11] This middle portion of the Right of Way is located approximately between Lots 103 and 112, and is not adjacent to the plaintiff's property. Although wooded, this section of the Right of Way was passable by at least some types of vehicles even prior to being cleared; Laval Jean built his house at 77 Milton Avenue, adjacent to Lot 103, in 1961, and brought concrete trucks in to pour the foundation by having them drive down Montcalm Avenue, over the Right of Way, to Lot 103 at the back of the new foundation. [Note 12] The Right of Way was also passable by foot: both Trottier and Boyajian crossed this section on foot. [Note 13] It could also be traversed by dirt bikes or other off-road vehicles.

11. West of this wooded section, toward the intersection of Edgewater Drive and Harris Pond itself, the westernmost portion of the Right of Way is paved with asphalt, to a width of perhaps twelve feet, with retaining walls on either side of the paved roadway, and has been so paved since at least the 1950s. [Note 14] This paved section has a fairly steep grade, and extends from Edgewater Drive to a point along the boundary of Lot 103. [Note 15]

12. At an undetermined date after 1996, a path was cleared through the wooded central section to better connect the cleared eastern section with the asphalt pavement of the western section of the Right of Way. [Note 16]

13. Paul Jean lived at Lots 98 and 99 from 1960 through 1978. During this period, his family and friends would frequently ride off-road vehicles through the wooded portion of the Right of Way.

14. In 1996, Paul Jean purchased and moved in to lots 99, 100, 101, and 103. The house on this group of lots is heated by a wood-burning stove. Wood is delivered to the property by a truck which turns off of Harris Pond Street onto the eastern section of the Right of Way, and drives into the yard of Lot 103. [Note 17] The Jean family has been storing wood on Lot 103 since prior to 1996, when Laval Jean stored wood there for the wood burning stove he constructed in 1981 to heat his adjacent home at 77 Milton Avenue. [Note 18]

15. At some point, Monique Jean, Laval Jean's sister, constructed a fence running east to west down the center of this eastern section of the Right of Way, enclosing a portion of the Right of Way. Paul Jean and Laval Jean continued to use the other, northern side of the eastern section of the Right of Way, which is the side adjacent to the plaintiff's property, to bring wood onto Lot 103.

16. Subsequently, Trottier parked a Jeep to block the northern half of the Right of Way that was still open. Laval Jean spoke with Trottier, and Trottier removed the Jeep. However, Trottier then again blocked that portion of the Right of Way with stacked pallets and other construction material.

17. On May 20, 2014, through counsel, Laval Jean and Pauline Jean sent Trottier a letter requesting the removal of the material. Trottier complied. [Note 19]

18. On June 11, 2014, counsel for Laval Jean sent a letter to Monique Jean requesting that she remove the fence, as it impeded Laval Jean's right to traverse the entire length of the way. [Note 20] Laval Jean also contacted the town of Blackstone and requested to see Monique Jean's permit for the fence. Monique Jean then removed the fence. [Note 21]

19. While living at 110 Harris Pond Street until 1964, and then once a week after 1966, Trottier and Boyajian would help Trottier's parents with yard work, such as raking and clearing yard debris. Until the 1980s, Trottier and his family burned this debris. [Note 22] After they stopped burning debris in the 1980s, they placed the debris in the Right of Way. [Note 23] Trottier did not clarify the frequency, duration, or location in the Right of Way of placement, nor did he specify the quantity or quality of debris.

20. Trottier testified that, when clearing the yard of 110 Harris Pond Street, his family would sometimes pile small rocks in the Right of Way. [Note 24] Trottier stated that, in his opinion, the rocks were large enough that a car would not be able to drive over them. [Note 25] Trottier again did not clarify where in the Right of Way these rocks were placed, their quantity, or the frequency of deposit. It was unclear whether Trottier was indicating that the rocks would be placed on the berm along the south edge of the Right of Way, or more centrally; it was also unclear whether these rocks were placed in the cleared, eastern section of the Right of Way abutting 110 Harris Pond Street, or further west on the wooded, central section of the Right of Way. [Note 26] In light of other testimony, I do not credit the implication of this testimony that the placement of rocks in the Right of Way made it impassable for vehicles or pedestrians.

DISCUSSION

The plaintiff's complaint articulates claims to try title (Count One), extinguishment of the defendants' easement by prescription (Count Two), abandonment of that easement (Count Three), and, in the alternative, plaintiff claims an easement by estoppel over the remainder of the way (Count Four). The defendants bring a counterclaim seeking a declaratory judgment (Counterclaim Count One) that Montcalm Avenue east of Harris Pond Street is a public way. [Note 27] They also claim an easement by prescription, implication, or estoppel (Counterclaim Count Two), and cross-claim for declaratory judgment against the town of Blackstone (Cross-claim Count One), requesting declarations that "the public has utilized Montcalm as a public right"; that this use by the public has been uninterrupted for a period of twenty years; and that the Town has used public funds and law enforcement to ensure that public use of Montcalm remains free from interference.

At the closing arguments, the parties stipulated, notwithstanding any deficiencies in the record, that both the plaintiff and the defendants (not including the Town, which did not participate) own the fee to those portions of the Right of Way adjacent to their properties to the

centerline, and had rights to pass and repass over the entirety of Montcalm Avenue between Harris Pond Street and Edgewater Avenue, whether by deed, by operation of G. L. c. 183, § 58, or otherwise, and that the only issues remaining in this case concerned whether such rights had been extinguished.

Plaintiff's Claims

I. Try Title

The plaintiff claims (and the parties have so stipulated) that she owns the fee in the portion of the Right of Way adjacent to 110 Harris Pond Street, pursuant to G. L. c. 183, § 58, and she further claims that the defendants' rights to pass and repass over that portion of the Right of Way have been extinguished by prescriptive use or by abandonment. The purpose of a try title action is "to allow a person holding record title to compel an adverse claimant to prove the merits of the adverse claimant's interest in the property." Abate v. Fremont Inv. & Loan, 470 Mass. 821 , 822 (2015). A try title action involves two distinct steps: "the 'first step' requires that the petitioner satisfy the jurisdictional elements of the statute and, if satisfied, the 'second step' requires the adverse claimant either to bring an action to assert the claim to title, or to disclaim an interest in the property." Id. Pursuant to the first step, "[t]he petitioner must satisfy these three jurisdictional elements: (1) that he holds 'record title' to the property; (2) that he is a person 'in possession'; and (3) the existence of an actual or possible 'adverse claim' clouding his record title. Id., quoting Blanchard v. Lowell, 177 Mass. 501 , 504-505 (1901).

Pursuant to the 2013 deed from Claire Trottier to the plaintiff, the plaintiff has record title to Lots 116, 118, and 119 as shown on the "Plan of Lots for Sale by Edwin Cook." She argues that, by operation of G. L. c. 183, § 58, as applied to this deed, she holds title to "one half" [Note 28] of the portion of Montcalm Avenue west of Harris Pond Street. Pursuant to the parties' stipulation at closing arguments, her ownership of the fee extends to the centerline, but only adjacent to her property boundaries.

G. L. c. 183, § 58, commonly known as "the derelict fee statute," provides:

Every instrument passing title to real estate abutting a way, whether public or private, watercourse, wall, fence or other similar linear monument, shall be construed to include any fee interest of the grantor in such way, watercourse or monument, unless (a) the grantor retains other real estate abutting such way, watercourse or monument, in which case, (i) if the retained real estate is on the same side, the division line between the land granted and the land retained shall be continued into such way, watercourse or monument as far as the grantor owns, or (ii) if the retained real estate is on the other side of such way, watercourse or monument between the division lines extended, the title conveyed shall be to the center line of such way, watercourse or monument as far as the grantor owns, or

(b) the instrument evidences a different intent by an express exception or reservation and not alone by bounding by a side line.

G. L. c. 183, § 58. This rule was intended "to meet a situation where a grantor has conveyed away all of his land abutting a way or stream, but has unknowingly failed to convey any interest he may have in land under the way or stream, thus apparently retaining his ownership of a strip of the way." Rowley v. Massachusetts Elec. Co., 438 Mass. 798 , 803 (2003). "The rationale of such decisions is apparently that the grantor is unlikely to want to reserve title to the fee of the way; if he does, he may avoid the effect of the presumption by contraindicating." Smith v. Hadad, 366 Mass. 106 , 108 (1974).

Accordingly, where a way and lots abutting that way are in common ownership, and the common owner conveys the abutting lots, the grantees of those deeds may implicitly receive some portion of the fee in the way itself as well. See id. Additionally, lot owners who acquire fee ownership of a portion of the way through operation of § 58 likewise acquire the right to use the way along its entire length. See Brennan v. DeCosta, 24 Mass. App. Ct. 968 , 968 (1987). These are the rights that the plaintiff and the defendants have stipulated each started with prior to any extinguishment of such rights by prescriptive use or otherwise.

II. Extinguishment by Prescription

Only the plaintiff's actions within the particular portion of the way that the parties have stipulated she actually owns are relevant to the court's analysis of extinguishment, as she may only extinguish an easement running across her own land. It was not entirely clear at trial whether the activities claimed by the plaintiff to contribute to the extinguishment of the defendants' rights occurred within the portions of the Right of Way to which the parties have stipulated she owns the fee. Notwithstanding this difficulty, I find and rule that whatever the extent of the plaintiff's ownership of the fee in the way and the consequential extent of the defendants' easement over this area, the evidence of the plaintiff's actions is wholly insufficient to prove extinguishment of whatever rights others may have over any portion of the Right of Way.

"A use of the servient tenement, to have the effect of extinguishing an easement in it must be wrongful. To be wrongful it must be of such a nature as to give rise to a cause of action in favor of the owner of the easement. To do this it must either interfere with a use under the easement or have such an appearance of permanency as to create a risk of the development of doubt as to the continued existence of the easement." Desotell v. Szczygiel, 338 Mass. 153 , 159 (1958), quoting Delconte v. Salloum, 336 Mass. 184 , 189 (1957). "To wholly extinguish an easement by prescription, the 'acts of the servient tenant [must be] utterly inconsistent with any right of the dominant tenant, manifestly adverse to every claim by it, and incompatible with the existence of the easement' for at least the prescriptive period of twenty years." Cater v. Bednarek, 462 Mass. 523 , 528 n.16 (2012), quoting New England Home for Deaf Mutes v. Leader Filling Stations Corp., 276 Mass. 153 , 159 (1931). Put another way, "a servient tenant's adverse acts must render use of an easement 'practically impossible for the [twenty-year] period required for prescription.'" Post v. McHugh, 76 Mass. App. Ct. 200 , 204-205 (2010), quoting New England Home for Deaf Mutes, 276 Mass. at 159. "Where the acts of the servient tenant render the use of only part of a right of way impossible, the easement is extinguished only as to that part." Cater v. Bednarek, supra, 462 Mass. at 528 n.16, quoting Yagjian v. O'Brien, 19 Mass. App. Ct. 733 , 736737 (1985).

Here, the evidence in the record demonstrates that, from at least the early 1970s until sometime after 1996, the portion of the Right of Way to the west of Lot 116, and approximately adjacent to Lots 103 and 112, has been obstructed by trees and assorted brush, although it appears Laval Jean was able to get a concrete truck through the way to pour concrete as early as 1961, and wood deliveries were made to Lot 103 at the rear of 77 Milton Avenue, over the Right of Way from Montcalm Avenue, at least as far back as 1996, and to some extent earlier than that. [Note 29] However, even to the extent that passage over the middle portion of the Right of Way was difficult because of the presence of trees and brush, the presence of such obstructions in this particular circumstance bears no relevance to the question of whether any rights of passage on the Right of Way have been extinguished. "For G. L. c. 183, § 58, to apply, the way need not be in existence on the ground, as long as it is contemplated and sufficiently designated." Hanson v. Cadwell Crossing, LLC, 66 Mass. App. Ct. 497 , 502 (2006). Easement rights in the Right of Way would therefore have come into being even had such a blockage been initially present. The continued presence of vegetation likewise would not serve any purpose with regard to extinguishment of this easement. Even where an easement is obstructed, it is only the "servient tenant's adverse acts [that] must render use of an easement 'practically impossible . . . .'" Post v. McHugh, supra, 76 Mass. App. Ct. at 204-205 (emphasis added; citation omitted). The presence of flora "cannot be said to constitute an adverse use by the servient tenant, in the absence of a showing that the servient tenant planted the trees and brush on the right of way." Desotell v. Szczygiel, supra, 338 Mass. at 159. See Sullivan v. Dart, 17 LCR 543 , 549 (Mass. Land Ct. 2009) (Sands, J.). There is no such evidence here.

The plaintiff must instead rely on active measures taken by the plaintiff or her predecessors in title to obstruct passage. The evidence of active interference with passage through the Right of Way is quite limited. Alfred Trottier and Monique Boyajian testified that they would occasionally place rocks and assorted "lawn debris" in the Right of Way. Neither provided any specificity as to the location in the Right of Way where these were placed, the quantity or size of either rocks or brush that was deposited in the way, the frequency with which the Trottiers placed these in the Right of Way, or whether these objects were consistently and uninterruptedly present. This testimony is wholly insufficient to carry the plaintiff's burden of showing interference that is "utterly inconsistent with any right of the dominant tenant." Cater v. Bednarek, supra, 462 Mass. at 528 n.16 (citation omitted). Without any clear evidence as to the quantity and location of the debris, it is impossible to determine whether it would have at any point served to entirely obstruct passage along any portion of the way, and based on other evidence of the use of the Right of Way by the defendants, I have found that passage was not effectively blocked by any activity of the plaintiff or her predecessors. It is at least apparent that the plaintiff's activities did not obstruct vehicular access to the portion of the Right of Way adjacent to Lots 116 and 118, as both Trottier and Boyajian testified that automobiles have driven and parked on this portion since the 1960s. Any such parking activity by the plaintiff's family was intermittent enough (testimony of parking on holidays) that it did not itself constitute an activity that would extinguish the rights of the defendants, and such parking activity demonstrates that the way was open and passable. Even if it is to be assumed that the debris strewn into the way by the plaintiff or her family was entirely placed beyond this in the wooded, central portion of the Right of Way approximately adjacent to Lots 112 and 103, there is little evidence as to its location or quantity within that particular area or its effectiveness in blocking passage. There was no testimony on that subject by any witness, and the photos which depict the Right of Way largely show it to be clear of any obstructing stones; the few in which any rocks are visible at all depict only a sparse scattering of small stones in the wooded area. [Note 30] There is altogether insufficient evidence to show that the debris placed by Trottier would have prevented passage through that particular area in the absence of the existing vegetation. Contrast Yagjian v. O'Brien, supra, 19 Mass. App. Ct. at 737 (finding easement extinguished through "maintenance of fencing impeding passage across the entire width of a right of way"); New England Home for Deaf Mutes v. Leader Filling Stations Corp., supra, 276 Mass. at 159 (where servient tenant "pursued a course of conduct with the deliberate design of excluding everybody . . . from entering upon the land in question").

Moreover, even if it could be assumed that the rocks and "lawn debris" did so obstruct the Right of Way at some point, a failure to provide sufficient proof that this obstruction was "continuous and uninterrupted" for the prescriptive period of twenty years necessarily prevents a finding of extinguishment. See Yagjian v. O'Brien, supra, 19 Mass. App. Ct. at 736. The evidence in the record simply indicates that the Trottiers began placing excess brush in the Right of Way at some point in the 1980s after they ceased burning it; as to the placement of rocks, the record provides no clarity as to when this practice began or ended, and does not detail the period during which rocks were present in the Right of Way. Thus, as to the Trottiers' placement of debris in the Right of Way, I find that at the very most a small quantity of small rocks were placed in a small section of the Right of Way for an indeterminate period of time. The evidentiary import of these actions is, needless to say, small, and I do not credit that these actions had the result of making any part of the Right of Way impassable.

Although the plaintiff or her predecessors in title appear to have undertaken a number of other acts to obstruct the Right of Way, each was quickly remedied. Trottier parked a Jeep in the Right of Way, but it was removed at Laval Jean and Pauline Jean's request. Trottier likewise blocked the Right of Way with construction debris, but this was also promptly removed at Laval Jean and Pauline Jean's request. The only other obstruction of the Right of Way described at trial was the construction of a fence running down its center. However, this was the act of Monique Jean, not the plaintiff or her predecessor, and the period of time for which the fence stood was likewise not clearly established. In any event, the fence did not prevent the defendants from using the side of the Right of Way adjacent to the plaintiff's property.

Accordingly, the plaintiff has failed to provide proof that she or her predecessors in title engaged in conduct sufficient in either duration or extent to extinguish any easement the defendants may have in any part of the way. The plaintiff's claim of extinguishment by prescription therefore fails.

III. Abandonment

With respect to plaintiff's claim that the defendants have lost their rights in the Right of Way by abandonment, at trial, plaintiff's counsel clarified that the plaintiff was no longer pursuing a theory of abandonment, and was only seeking relief on a theory of extinguishment by prescription. As the plaintiff made no formal motion to dismiss Count Three of the complaint, though, the court will nonetheless briefly address its lack of merit. "Abandonment of an easement requires a showing of intent to abandon the easement by acts inconsistent with the continued existence of the easement." Cater v. Bednarek, supra, 462 Mass. at 528 n.15. "[N]onuse itself, no matter how long continued, will not work an abandonment." Id., quoting Desotell v. Szczygiel, supra, 338 Mass. at 159.. "Similarly, nonuse combined with failure to clear natural trees and brush for longer than the prescription period will not work an abandonment of an easement." Halvarson v. Teleen, 90 Mass. App. Ct. 1124 (2017) (Rule 1:28 Decision). There is no evidence in the record of any acts by the defendants demonstrating any intent to abandon an easement over the Right of Way. In fact, they took active measures to ensure that obstructions to the Right of Way were promptly removed. As there is nothing in the record to support a claim of abandonment, Count Three will be dismissed.

IV. Easement by Estoppel

The plaintiff argues that she is entitled to easements by estoppel over the portions of the Right of Way owned by the defendants. The parties' stipulation as to the rights of each under G. L. c. 183, § 58, would appear to render this count moot. Based solely on the stipulation, an easement by estoppel exists for the benefit of the plaintiff. An easement may be created by estoppel in two ways.

"First, when a grantor conveys land bounded by a street or way, he, and those claiming under him, are estopped to deny the existence of the street or way, and his grantee acquires rights in the entire length of the street or way as then laid out or clearly prescribed. See Casella v. Sneirson, 325 Mass. 85 , 89 (1949). Second, when a grantor conveys land situated on a street in accordance with a recorded plan that shows the street, the grantor, and those claiming under him, are estopped to deny the existence of the street for the distance as shown on the plan."

Blue View Constr., Inc. v. Franklin, 70 Mass. App. Ct. 345 , 355 (2007). "The easement over that way acquired by the grantee 'embraces the entire length of the way, as it is then laid out or clearly indicated and prescribed.'" Post v. McHugh, supra, 76 Mass. App. Ct. at203, quoting Casella v. Sneirson, supra, 325 Mass. at 89 . These principles form the basis for both the plaintiff's and the defendants' easements over the entirety of the Right of Way.

Defendants' Claims

V. Establishment of a Public Way

As to the counterclaim and cross-claim concerning the public use of the way and the Town's maintenance thereof, the town has indicated in response that it makes no claim that the Right of Way is or was a public way. The town maintains that the paved portion of Montcalm Avenue to the east of Harris Pond Street is a public way, and the parties do not appear to dispute this; the Right of Way at issue in this case is the portion of Montcalm Avenue to the west of Harris Pond Street. At trial, there was no evidence presented by any party even tangentially touching upon the issue of whether the Right of Way was a public way, and no evidence was presented concerning the town's historical or present activities with respect to the Right of Way. Furthermore, although the defendants argue that there has been general use of the Right of Way by the public for a period of twenty years, this would bear no relevance to the question of whether the town has accepted property as a public way, even if it were supported by the evidence. Accordingly, defendants' counterclaim for a declaratory judgment that the public has used the Right of Way and the town has maintained it as such, is dismissed; likewise, the defendants' cross-claim against the town requesting a similar declaration is also dismissed.

VI. Easement by Prescription, Implication, or Estoppel

1. Prescriptive Easement

The defendants claim, in the event that the court finds that the plaintiff had successfully extinguished any easement that they held, that they have re-established an easement over the right of way by prescription, implication, or estoppel. Based on the parties' stipulation recognizing the initial rights of each to the Right of Way, and my findings that the defendants' rights have not been extinguished by prescriptive use or by abandonment, this claim is moot.

2. Easement by Implication

Though the defendants have presented a claim for an easement by implication, they have offered no further arguments on this front, and in any case, this claim, as well, is moot.

3. Easement by Estoppel

The defendants finally claim to hold an easement by estoppel. As noted above, an easement may be created by estoppel when a grantor with unity of title in both the way and the conveyed property either describes the property as bounded on the way, or references a plan which depicts it as such. See Blue View Constr., Inc. v. Franklin, supra, 70 Mass. App. Ct. at 345. Based solely on the stipulation of the parties, and for the same reason that the plaintiffs have an easement by estoppel over the entirety of the Right of Way, so do the defendants.

CONCLUSION

For the reasons stated above, the plaintiff and the defendants have rights over the Right of Way, including the right to pass and repass for all the purposes for which ways are commonly used, and neither party's rights as aforesaid have been extinguished by prescription or abandonment.

Judgment to issue accordingly.

KATIE L. LEAHEY v. MONIQUE H. JEAN, KOREEN OBERT, LAVAL F. JEAN, PAULINE S. JEAN, PAUL D. JEAN, and TOWN OF BLACKSTONE.

KATIE L. LEAHEY v. MONIQUE H. JEAN, KOREEN OBERT, LAVAL F. JEAN, PAULINE S. JEAN, PAUL D. JEAN, and TOWN OF BLACKSTONE.