This dispute could be viewed as a slowly developing train wreck. It originates in the late 1980s, when the needs of Boston's Central Artery/Third Harbor Tunnel Project (also known as the "Big Dig"), the city's most consequential public works project since the Second World War, cast a shadow over the aspirations of Nicholas J. and Katerina Contos. Parcel by parcel, the Contoses had acquired substantial properties within what's now called the Seaport District in South Boston. Today that District is flush with rental housing and residential condominiums, hotels, office buildings, a convention center, and restaurants. That wasn't true in '80s, but the Contoses foresaw the area's possibilities and hoped to profit from them. (While the Court recognizes that most in the '80s wouldn't have called today's Seaport District the "Seaport District," the Court nonetheless will refer to the area by its modern name.)

Many of the Contos properties lay near the First Street Yard, a railyard once owned by the Penn Central Railroad. In 1985, the Penn Central's successor, Consolidated Rail Corporation (or "Conrail"), agreed to sell to the Contoses some of Conrail's Seaport District properties, as well as the rights to develop the airspace (sometimes called "air rights") over other Conrail properties in the District. But Conrail intended to keep the First Street Yard and related tracks, which Conrail still used.

In the late '80s, the Big Dig's planners at what was then the Massachusetts Department of Public Works ("Mass DPW," now defendant Massachusetts Department of Transportation, or "MDOT") decided they needed to build into the Seaport District a two-lane "haul road." They hoped that the road would keep construction and other heavy vehicles off of Boston's city streets during the Big Dig. They concluded that the best location for the haul road lay along Conrail's Boston Terminal Running Track, or the "BTRT" for short. The BTRT led to the First Street Yard. When told that Mass DPW intended to take by eminent domain a portion of the BTRT and move the tracks elsewhere, Conrail told Mass DPW that it would have to move the First Street Yard too.

Several Contos properties, or properties that Conrail had agreed to sell to the Contoses, were a logical place for relocating both the BTRT and the First Street Yard. Mass DPW proposed to take the Contos properties in fee, but the Contoses objected. They warned Mass DPW they would fight any taking in court. That convinced Mass DPW to spend the next two years negotiating with Conrail and the Contoses over an arrangement that would satisfy Mass DPW's needs to build the haul road, Conrail's desire to have a Seaport District railyard, and the Contoses' wishes to maximize the return on their real-estate investments.

The parties' negotiations appeared to end successfully. They produced three instruments, which this decision will call the "settlement documents." One was a Final Settlement Agreement, which Mass DPW, Conrail and the Contoses signed in August 1991 (the "FSA"). The second was an Air Rights Agreement, which the same parties executed in September 1991. The third was an agreed Order of Taking, which Mass DPW recorded on October 23, 1991.

The parties to this case are the successors to the ones that signed the settlement documents. The parties to this case dispute what those documents say. While the Court will dive into the specifics of those documents later in this decision, in general terms they allowed Mass DPW to take in fee, under the agreed Order of Taking, Conrail's Seaport District properties, several Contos properties, and some of the Contoses' air rights. They also permitted Mass DPW to relocate portions of the First Street Yard to several Contos properties over which Mass DPW promised to take (again, via the agreed Order of Taking) only temporary and permanent easements. The settlement allowed Mass DPW to use the temporary easements only through October 23, 2003, during which time the department expected to complete construction of the haul road and other Big Dig infrastructure. The settlement also permitted Mass DPW to place a "Permanent Rail Yard" (the relocated First Street Yard) and the relocated BTRT (which this decision will call the "New BTRT") within the permanent easements created via the agreed Order of Taking. The parties to the settlement acknowledged that Mass DPW was taking the permanent easements for the benefit of Conrail. The settlement provided that once the Permanent Rail Yard was built, the Contoses could build over the permanent easements (which were limited in height to 20'6"), subject to the terms of the settlement documents.

After 1991, Mass DPW built the Permanent Rail Yard, the New BTRT, and the haul road (now known as the South Boston Bypass Road). By 2003, those portions of the Big Dig that

relied on the 1991 temporary easements were complete. Up to that time, the Contoses couldn't develop the properties that the 1991 temporary and permanent easements encumbered. Further complicating matters, in 2000 the Massachusetts Convention Center Authority (the "MCCA") took by eminent domain many of the Contoses' Seaport District holdings to build what's now the Boston Convention and Exhibition Center. Some of the properties that the MCCA took were already subject to the 1991 permanent easements.

The MCCA's takings sharply reduced the Contoses' holdings along the South Boston Bypass Road. They left, however, a portion of one property that the 1991 settlement calls Parcel 60-E-RR-5. (The "E-RR" in the Parcel's name indicates that, under the FSA, the parcel was subject to one of the permanent railroad easements created via the agreed Order of Taking.) Originally, Parcel 60-E-RR-5 had an area of 50,930 square feet. The MCCA's taking reduced the area to 29,821 square feet. (When this decision hereafter speaks of Parcel 60-E-RR-5, the Court is referring to the 29,821 square-foot remnant unless otherwise noted.) The Parcel's current owner is plaintiff B&W Second LLC ("B&W"). B&W is owned and managed by Anastasia Contos, the daughter of Katerina and the now-deceased Nicholas J. Contos. Katerina and Nicholas were paid $780,000 under the 1991 settlement for Mass DPW's taking of a permanent railroad easement (the "Permanent Easement") across original Parcel 60-E-RR-5.

The parties to this lawsuit - B&W, defendant MDOT, defendant Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority (the "MBTA"), and defendant/intervenor CSX Transportation, Inc. ("CSXT") - agree that the Permanent Easement encumbers all of Parcel 60-E-RR-5. The parties further agree that MDOT now holds the dominant estate under the Permanent Easement. (As will be explained in a moment, the parties' agreement on that issue is recent.) In May 2017, MDOT announced it had agreed to let the MBTA use various areas, including Parcel 60-E-RR-5,

for the construction and operation of a "test track" and related facilities (the "Test Track" or "Test Track Project"). The MBTA operates a subway system in the greater Boston metropolitan area. One of its subway lines, the Red Line, runs on railroad tracks; the subway cars have electric motors that receive power from a third rail. The MBTA has decided to replace many of its Red Line subway cars, but it won't place the new cars in service without testing each first. The MBTA also wants to avoid testing the new cars on the tracks of the Red Line itself, as that would disrupt passenger service and regular maintenance of the Red Line.

After studying several potential sites for the Test Track, the MBTA chose to put the track in the right of way for the New BTRT, which runs southwest to northeast. The selected location includes the portion of the New BTRT's right of way that enters Parcel 60-E-RR-5 from the southwest. The MBTA originally planned to have the test track split into three tracks once it reached Parcel 60-E-RR-5. Two of the tracks, intended for storage purposes, were to terminate within or near the northeastern end of Parcel 60-E-RR-5. The third track was to end within a testing building to be built on land just northeast of Parcel 60-E-RR-5.

In February 2018, B&W sued MDOT and the MBTA in this Court. B&W's operative pleading is its Second Amended Verified Complaint. It contains two counts. In Count I, B&W seeks a declaration "as to the rights vel non of Defendants to enter upon and utilize the [Permanent] Easement and [Parcel 60-E-RR-5] for the purpose of installation of the Red Line Test Track." As of filing of its Second Amended Verified Complaint, B&W contended that MDOT and the MBTA had no such rights. In Count II, B&W asks for an injunction prohibiting MDOT and the MBTA from installing any part of the Test Track on Parcel 60-E-RR-5.

Two events forced B&W to narrow its original objectives in this suit. First, in August 2018, MDOT and the MBTA stated they would start Test Track construction on Parcel 60-E-RR-

5, and that if the Court were to rule against them on Count I, they likely would proceed with a further taking on the Parcel rather than halt construction. In practical terms, that announcement mooted B&W's claims in Count II.

The second event had to do with one of B&W's chief arguments for why MDOT and the MBTA couldn't do anything on Parcel 60-E-RR-5. MDOT claims that it has succeeded to Conrail's rights and interests under the Permanent Easement. When it filed suit, B&W contended that Conrail and its successors in interest hadn't actually conveyed those rights, and that Conrail still held them. B&W's pursuit of that argument led, first, to CSXT's intervention in this case and, later, to a March 2019 confirmatory release deed. In that deed, Conrail granted to CSXT "and those holding by, through or under CSXT by instruments of record, including without limitation [MDOT], all right, title and interest" of Conrail in the Permanent Easement.

Once Conrail signed that deed, B&W could no longer argue that MDOT (and, by extension, the MBTA) had no rights to use Parcel 60-E-RR-5. B&W could dispute only whether MDOT and the MBTA had exceeded their rights under the Permanent Easement.

In late 2018 and into 2019, the parties moved and cross-moved for partial summary judgment as to their rights under the Permanent Easement. In September 2019, the Court granted B&W's cross-motion in part and denied MDOT and the MBTA's motion in its entirety. The remaining issues in this case required a trial. The Court took a view of Parcel 60-E-RR-5 (the Test Track was still under construction) and heard trial testimony between January 27 and January 30, 2020. The Court heard closing arguments on February 26, 2020. After closing arguments, the parties told the Court that they wished to discuss settlement. The parties did so through June 11, 2020, at which point they asked the Court to decide the case.

Having heard the parties' witnesses, having reviewed their evidence, having listened to the arguments of counsel, and in light of the Court's view of Parcel 60-E-RR-5, the Court FINDS the facts described earlier in this decision as well as those listed in the numbered paragraphs below. The Court concludes that the 1991 settlement documents allow MDOT and the MBTA to build the Test Track over Parcel 60-E-RR-5, but they may have to move (or allow the relocation of) certain Test Track facilities if and when B&W presents a plan for developing its air rights over the Parcel that doesn't call for placing building-support columns in protected track corridors.

Here are the Court's additional findings of fact:

The FSA and the Permanent Easements

1. Section IV.A of the FSA, "Permanent Rail Yard Easement Area," provides:

1. The Commonwealth [Note 1] shall record an Order of Taking to acquire a Permanent Easement (hereinafter "Permanent Easements"), for the benefit of Conrail [Note 2] for railroad purposes in and over the parcels of land designated on the Easement Plan as Parcels 60-E-RR-6 and 60-E- RR-5. The boundaries of the area constituting the Permanent Easements shall hereinafter be referred to as the "Permanent Easement Area" and are shown on the "South Boston Haul Road General Plan Yard Area, Sheets 1-3" (hereinafter the "Permanent Rail Yard Plan") . . . .

2. Said Permanent Easement Area shall contain not more than two (2) rail yard storage tracks with vertical clearances of 20'6" as set forth in Part IV, Section A(4) below and one (1) gravel access road, all as shown on said Permanent Rail Yard Plan.

. . .

4. Upon the expiration of the Temporary Easements, the Permanent Easement Area shall include the air space up to a height of 20'6" measured from the top of the rails which are to be placed upon the proposed final grade . . . .

5. Conrail, the Commonwealth and Contos agree that Contos [Note 3] and his designees, shall, after giving prior notice to Conrail and the Commonwealth, as the case may be, have the right to enter into the Permanent Easement Area for such purposes and to make, without limitation, tests, borings, surveys, plans or to take other actions, including without limitation, construction activities related to the Contos Development described in Part VI, Section A, provided said activities do not unreasonably interfere with, disrupt or impede the construction, maintenance or use by Conrail (pursuant to Part IV, Section B) . . . of the Permanent Easement Area. . . .

2. Trial Exhibit A-1 is the Permanent Rail Yard Plan. The Plan depicts (among other things) original Parcel 60-E-RR-5.

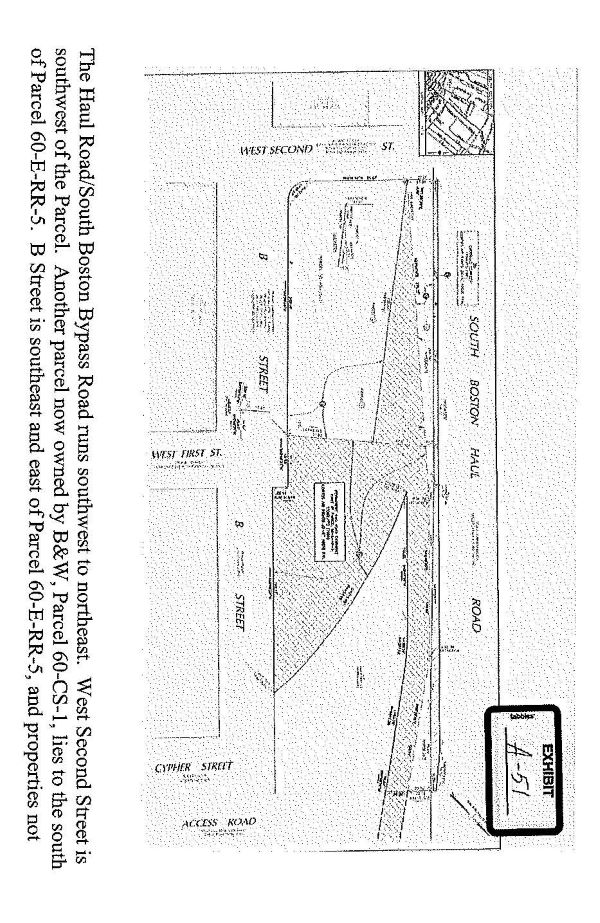

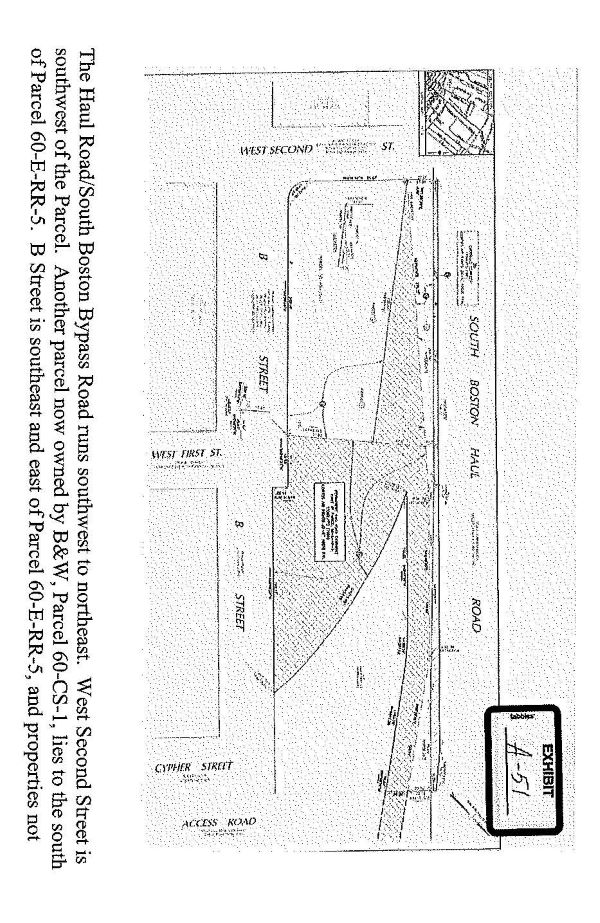

3. As shown on Trial Exhibit A-51, the "remnant" Parcel 60-E-RR-5 resembles a highly stylized clothes iron.

The Haul Road/South Boston Bypass Road runs southwest to northeast. West Second Street is southwest of the Parcel. Another parcel now owned by B&W, Parcel 60-CS-1, lies to the south of Parcel 60-E-RR-5. B Street is southeast and east of Parcel 60-E-RR-5, and properties not

owned by B&W lie northeast of the Parcel. The Court will call the thin strip of Parcel 60-E-RR- 5 that extends northeast from the bulk of the Parcel the "Handle."

4. Northeast of original Parcel 60-E-RR-5's Handle was an abutting parcel, Parcel 60-E-RR-6. The Permanent Rail Yard Plan shows, along the northwestern sides of original Parcel 60-E-RR-5 and Parcel 60-E-RR-6, a "10' Overbuild Corridor." That Overbuild Corridor is parallel to, and separates Parcels 60-E-RR-5 and -6 from, the proposed Haul Road. The Overbuild Corridor that's adjacent to the Haul Road comes as close as 1.39 feet to current Parcel 60-E-RR-5. (The width of that Overbuild Corridor isn't consistently ten feet in the areas closest to today's Parcel 60-E-RR-5, but that varying width isn't relevant to any of the issues in this case.) The Permanent Rail Yard Plan shows a second Overbuild Corridor southwest of some of the Contos properties. That corridor runs parallel to the Overbuild Corridor that runs along the Haul Road. The second Overbuild Corridor ends some distance northeast of Parcel 60-E-RR-5. In other words, the Permanent Rail Yard Plan never provided for two Overbuild Corridors adjacent to Parcel 60-E-RR-5, which wasn't the case for other Contos properties on the Plan.

5. Section VI.A of the FSA, "Contos Development Property," provides:

Subsequent to the expiration of the Temporary Easements, Contos intends to develop, to the extent permitted by law, the property owned by Contos which is located in the vicinity of the Haul Road/South Boston Bypass Road Projects. That property, which shall be referred to as the "Contos Development Property" [sic] consists of the following:

1. All of the land, and all of the air space above the land, including certain air space, subject to Exhibit E, located within the "Contos Property" as that term is defined in Part II of this Settlement Agreement, with the exception of [certain parcels not relevant to this case].

. . .

3. Subject to Exhibit E, upon the termination of the Temporary Easements, the air space beginning 20'6" above the top of the rails located upon the final proposed grade as shown on Exhibit D located over Parcels 60-E-RR-6 and 60-E-RR-5. . . .

6. According to Part II of the FSA, Parcel 60-E-RR-5 is part of the "Contos Property."

7. Section IV.B(2) of the FSA, under "Permitted Use of the Permanent Easements," provides: "After expiration of the Temporary Easements, the Permanent Easements shall be used by Conrail (i) for construction and maintenance of the [Permanent Rail Yard] consisting of such railroad tracks, facilities and appurtenant systems as are shown on the Permanent Rail Yard

Plan . . . ; and (ii) for the purposes set forth in Part IV, Section B(1)(iii) above."

8. According to the Permanent Rail Yard Plan, Parcel 60-E-RR-5 is inside the Permanent Rail Yard.

9. Section IV.B(1)(iii) of the FSA allows Conrail to use the Permanent Easements "for use by Conrail, its authorized customers, agents and assigns for railroad purposes (freight or passenger), including the loading and unloading of rail cars or containers, the classifying and assembling of trains, the temporary storage of operating rolling stock or for such other railroad purposes related to the transportation of freight and commodities by rail."

10. Section IV.C of the FSA, "Modification of Permanent Rail Yard Plans," provides in part:

The permanent yard track layout on the Permanent Easements shall be in accordance with the Permanent Rail Yard Plan . . . Modifications to the Permanent Rail Yard Plan may be made by Conrail if either (i) the modified track layout on the Permanent Easement remains within the railroad track clearance corridors identified on the Permanent Rail Yard Plan and in no material way adversely impacts the interests of Contos, or (ii) the modified track layout is approved in writing by Contos in consultation with Conrail.

11. Part V of the FSA provides:

The Commonwealth, Conrail and Contos agree that simultaneously upon the execution of this Settlement Agreement, the parties shall execute the Air Rights Agreement attached hereto as Exhibit E and made a part of this Settlement Agreement . . . Contos shall record Exhibit E prior to the recordation of the Order of Taking. . . .

12. Part XIV of the FSA states that "[t]he proposed Order of Taking is attached to this Settlement Agreement as Exhibit B." The parties to the FSA agreed that Exhibit B was what the FSA called the "Order of Taking."

The agreed Order of Taking

13. The provisions of the Order of Taking that pertain to the Permanent Easements state this:

* "Easements are hereby taken in parcels 60-E-RR-1, 60-E-RR-5 and 60-E-RR-6 . . . for the relocation of the facilities of the Consolidated Rail Corporation . . . ." (Order of Taking at 25. [Note 4])

* "Said easements (i) shall be used for railroad purposes only . . . and (iii) shall be subject to the rights of the owner of the underlying fee as hereinafter provided." (Id. at 26.)

* "Said railroad easements are acquired in limited vertical dimension only, said area being limited to a height of 20'6" above the top of the rails to be placed thereon. Included in the easements, however, is the unlimited right to utilize the air rights above 20'6" for twelve (12) years following the date of recording of this taking. Thereafter, the use of said easements shall be subject to the rights of the owner of the air rights so reserved to use the area subject to the easements as reasonably may be required, subject to the approval of the party or parties having the benefit of the easements, for access to and to support the uses of the air rights." (Id. at 27-28.)

The Air Rights Agreement

14. Paragraph 3 of the Air Rights Agreement states:

Conrail and Contos agree that Exhibit "One" [to the Air Rights Agreement, hereafter "Exhibit One"] shall govern the construction and maintenance of any building or buildings, together with the suitable and necessary walls, columns, footings, foundations, drainage, communications and utility systems and other related support structures or any such building or buildings, in, on, or above the subsurface and surface areas within the ten foot (10') wide Over Build corridors shown on [the Permanent Rail Yard Plan] or outside the aforesaid Over Build corridors in the subsurface of Parcel 60-CR-1, and Parcels 60-E-RR-5 and 60-E- RR-6 (Parcels 60-E-RR-5 and 60-E-RR-6 comprise the Permanent Rail Yard Easement Area located upon the land of Contos).

15. Paragraph 5 of the Air Rights Agreement states: "Conrail and Contos agree that the terms, restrictions and conditions of Exhibit 'One' . . . are covenants which run with the land shown as Parcels 60-CR-1, 60-E-RR-5 and 60-E-RR-6 . . . ."

16. Exhibit One is a fifteen-page, double-spaced document containing 23 sections. Its §1 provides:

Contos . . . shall have the right and privilege to locate, construct, and install as well as maintain and renew in the surface and subsurface areas within the [Overbuild C]orridors suitable and necessary walls, columns, footings, foundations, drainage, communications and utility systems and related support structures necessary for the support of any future building or buildings and related facilities erected in the air space located above a horizontal plane twenty feet and six inches (20'6") above the top of the proposed rails which are to be placed upon the final proposed grade of . . . the Permanent Rail Yard Easement Area . . . . Contos shall have the right to construct, install and maintain any drainage, communications and utility systems necessary to service any future building or buildings erected in the aforesaid air space below the aforesaid horizontal plane and outside the [Overbuild C]orridors only at such locations and with such dimensions and clearances as shall not in the judgment of the Chief Engineer of Conrail interfere with the proper and safe operation of the railroad of Conrail. Contos shall have the right to enter into the [Overbuild C]orridors . . . and the Permanent Rail Yard Easement Area to maintain and keep in repair said walls, columns, footings, foundations, drainage, communications and utility systems and related structures which Contos hereby covenants and agrees to do at his sole cost and expense . . . . Title to the aforesaid walls, columns, footings, foundations, drainage, communications and utility systems and other related structures constructed by Contos shall be vested in Contos and the same shall be maintained and kept in repair by Contos at his sole cost and expense.

17. Section 2 of Exhibit One provides in part:

[W]ithin the perimeter of the Permanent Rail Yard Easement Area and up to a height of [20'6"] from the top of the proposed rails located on the final proposed grade . . ., Conrail shall have the right to construct and maintain [the Permanent Rail Yard] and all other necessary appurtenant facilities, including, but not limited to, signal, switching and lighting equipment, conduits and drain lines for the use by Conrail. The operation of the BTRT and the Permanent Rail Yard by Conrail shall not unreasonably disturb or affect any future building or buildings or related support structures to be constructed by Contos above the BTRT or the Permanent Rail Yard Easement Area. Contos hereby acknowledges that the normal noise, vibration and exhaust associated with rail operations do not constitute an unreasonable disturbance to the future buildings or related support structures and utilities of Contos.

18. Section 3 of Exhibit One provides:

The preliminary and final plans and specifications for suitable and necessary walls, columns, footings, foundations and drainage, communications and utility systems to be erected in the [Overbuild C]orridors necessary to support any building or buildings constructed above Parcel 60-CR-1 and the Permanent Rail Yard Easement Area, and, with respect to any drainage, communications and utility systems to be constructed in the surface or subsurface of the Permanent Rail Yard Easement [A]rea necessary to service any building or buildings constructed above the BTRT or the Permanent Rail Yard, shall be submitted to the Chief Engineer of Conrail for his review and approval before construction is commenced . . . . The approval of the Chief

Engineer of Conrail shall not be unduly delayed or unreasonably withheld. In the event Contos desires to construct or install any structures, facilities, drainage, communications and utility systems or other improvements within the [Overbuild C]corridors, or above 20'6" above the top of the rails located upon the final proposed grade . . . , or with respect to subsurface drainage, communications and utilities systems within . . . the Permanent Rail Yard Easement Area, Conrail shall grant approval therefor, provided such construction and installations shall not unreasonably interfere with the operation and maintenance of the BTRT and the Permanent Rail Yard by Conrail. Such construction and installations shall be approved by the Chief Engineer of Conrail before construction is commenced . . . . The construction, maintenance, repair and renewal work located within Parcel 60-CR-1, the Permanent Rail Yard Easement Area, or proximate thereto, shall be done at such time and in such manner as will be satisfactory to the Chief Engineer of Conrail so as not to unreasonably interfere with or endanger the railroad operations of Conrail.

19. Section 4 of Exhibit One provides:

Contos at his sole cost and expense shall take all necessary measures to protect all Conrail rail operations, railroad equipment, track and related facilities including, without limitation, duct lines, power lines, signal and communication systems, drainage lines and other similar systems located within . . . the Permanent Rail Yard Easement Area during the course of construction, maintenance, or operation of any building or buildings or other structures. Contos agrees that during the course of construction no structures or equipment of Contos shall unreasonably interfere with any railroad structure or facility (including, but not limited to, duct lines, pipes, cables, conduits, drainage ditches and signal, electric power and communications lines) located within . . . the Permanent Rail Yard Easement Area except that if, during the course of construction, it becomes necessary for Contos to interfere with any railroad facilities located in . . . the Permanent Rail Yard Easement Area, such construction shall be carried out only after Contos has obtained the prior written approval of the Chief Engineer of Conrail and in accordance with such reasonable conditions relating to safety and railroad operations as the Chief Engineer shall prescribe . . . . After construction has been completed, Contos shall not interfere with the use of railroad equipment and facilities without the prior written approval of the Chief Engineer of Conrail, provided, however, such approval shall not be unduly delayed or unreasonably withheld. . . .

20. Section 9 of Exhibit One provides:

During construction of supporting walls, columns, footings, foundations, drainage, communications and utility systems or support structures . . . below the aforesaid 20'6" horizontal plane . . . above . . . the Permanent Rail Yard Easement Area, and until the work upon the first floor of the permanent structure or structures shall have been completed . . ., as well as during any work from time to time in the future . . . above said . . . Area, Contos shall be required to pay the actual costs and expenses for such protection as Conrail shall deem necessary to safeguard the employees and rail operations of Conrail located beneath any building or buildings constructed by Contos.

21. Section 16 of Exhibit One provides:

The Chief Engineer of Conrail agrees to reasonably cooperate in the development of the Contos air rights located above . . . the Permanent Rail Yard Easement Area and will not unduly delay the approval or disapproval of any plans, construction or installations relating to, or concerning, the development of the Contos air rights above . . . the Permanent Rail Yard Easement Area. Such approval or disapprovals shall not be unreasonably withheld and shall not be unduly delayed nor shall consent of the Chief Engineer whenever necessary be unreasonably withheld or unduly delayed. The Chief Engineer or his designee shall be available for consultation and advice and shall be cooperative with Contos in that respect. Whenever, under the terms of this instrument the opinion of the Chief Engineer is controlling, it is intended that such opinion shall be informed and reasonable.

22. Section 23 of Exhibit One provides:

Conrail and Contos agree that the use, operation, maintenance, renewal and safety of the BTRT, the Permanent Rail Yard and related railroad facilities are of utmost importance. Contos shall not do anything at any time or from time to time which shall jeopardize or interfere with the free, safe and continuous use, operation, maintenance and renewal of the said BTRT, the Permanent Rail Yard and related railroad facilities as may hereafter exist. Nothing contained herein however, except the obligation to maintain and repair, shall require Contos, after the plans and specifications for any necessary walls, columns, footings, foundations, drainage, communications and utility systems and related support structures have been approved as herein before required, to alter, modify or otherwise change or reconstruct any such structures, systems or any building or buildings. . . .

The Test Track Project's "modifications" to the Permanent Rail Yard Plan

23. The Permanent Rail Yard Plan shows three proposed tracks crossing what's now Parcel 60-E-RR-5. The three tracks are (1) the New BTRT, (2) a spur track off the New BTRT (the "BTRT Spur"), and (3) a third spur track (the "Third Spur"). The Plan shows the Third Spur intersecting the New BTRT just southwest of Parcel 60-E-RR-5. At trial, Roger Gagnier, an engineer and project manager for the Test Track project, identified the New BTRT, the BTRT Spur, and the Third Spur by number (1, 2 and 3) on a trial chalk that is an enlargement of Trial Exhibit A-33. The Court accepts Mr. Gagnier's identification of the three tracks.

24. The Permanent Rail Yard Plan did not devote the entirety of today's Parcel 60-E- RR-5 to tracks and their clearance corridors. The Plan sited within Parcel 60-E-RR-5, for example, a proposed "gravel access road." The access road was to begin on the southeast edge of the Parcel along B Street, then curve to the northeast (crossing the BTRT Spur and the Third Spur), and exit Parcel 60-E-RR-5 below its Handle. Further to the northeast, the access road was to run parallel to the two rail storage tracks planned for other Contos parcels. There is a

noticeable area on Parcel 60-E-RR-5 that's east of the proposed gravel access road, but above B Street, that is free of any tracks, clearance corridors, and access roads.

25. The MBTA has installed or will install on Parcel 60-E-RR-5 two tracks. One is a storage track that exits and later reenters the Parcel in its Handle. The other track is a spur that leads to a vehicle testing shed located on land northeast of Parcel 60-E-RR-5.

26. Each of the proposed tracks consists of two "running rails" plus an electrified third rail. Parcel 60-E-RR-5 also is (or will be) the site of a mobile traction power substation, an electrical transformer, electrical switchgear, underground utilities, and parking for MBTA personnel and authorized visitors. A gated fence will enclose the entirety of Parcel 60-E-RR-5 except for where the Test Track enters Parcel 60-E-RR-5 from the southwest.

27. None of the Test Track elements described in Findings 25-26 above corresponds with what's shown on the Permanent Rail Yard Plan. But none of the Test Track elements has been (or will be) built within any Overbuild Corridor, nor will any part of the Test Track be built more than 20'6" above the top of the Test Track's tracks.

28. Neither the FSA nor the Permanent Rail Yard Plan "identifies," within the meaning of Part IV.C of the FSA, the "railroad track clearance corridors" for the tracks that appear on the Plan. It's undisputed, however, that as of the 1991 settlement, the minimum legally allowed track-clearance corridor was 8.5' from the centerline of each track, plus one additional inch of clearance for each degree of track curvature. Trial Exhibit A-34 depicts the minimum statutory clearance corridors around the tracks described in Finding 23 above.

29. The Court credits Mr. Gagnier's testimony that the tracks described in Finding 25 above are within the clearance corridors of the tracks described in Finding 23 above.

30. MDOT and the MBTA have not received approval in writing from B&W to build the Test Track Project.

B&W's Efforts to Develop Parcel 60-E-RR-5

31. B&W first contacted MDOT and the MBTA to discuss the Project and B&W's possible development of Parcel 60-E-RR-5 in the spring of 2017, after MDOT and the MBTA's announcement of the Test Track Project. B&W first met with MDOT and the MBTA about development issues in June 2017. B&W posed several questions to MDOT and MBTA during that meeting, all pertaining to the Test Track Project. B&W did not provide any development plans during the meeting.

32. In July 2017, B&W engaged a civil engineering firm, Stantec, to prepare preliminary designs for development of Parcel 60-E-RR-5 and adjoining Parcel 60-CS-1. Between August 2017 and February 2018, Stantec provided to B&W several preliminary designs. B&W presented to MDOT and the MBTA in the fall of 2017 portions of one preliminary design set dated September 1, 2017. At that time, MDOT and the MBTA hadn't finalized the locations of the Test Track Project's tracks or their associated clearance corridors.

33. The last preliminary designs that B&W presented to MDOT and MBTA outside of settlement discussions, and the only development designs B&W asked this Court to consider at trial, are Trial Exhibits A-25, A-26, A-27, A-28, A-29, A-30, and A-31 (collectively, the "2018 Designs"). All are dated February 23, 2018, or one week after B&W filed this lawsuit.

34. The 2018 Designs call for construction of a residential apartment building on Parcel 60-CS-1 and extending over Parcel 60-E-RR-5. All of the 2018 Designs contemplate the "core" of the building being on Parcel 60-CS-1. All of the 2018 Designs depend on construction of columns and other supports on the Overbuild Corridor adjacent to Parcel 60-E-RR-5.

35. Among the 2018 Designs is Trial Exhibit A-31. Anastasia Contos described it as one that attempted to avoid as much as possible what B&W understood, at the time Stantec was preparing Exhibit A-31, were the locations of Parcel 60-E-RR-5's clearance corridors and MBTA's proposed Test Track facilities. (After Stantec prepared Exhibit A-31, the MBTA modified the Project to eliminate one of two proposed storage tracks, the one that was closer to the South Boston Bypass Road.)

36. During cross-examination, Mr. Gagnier identified on a chalk of Exhibit A-31 a column, Column #1, that is within the clearance corridor of the Project's remaining storage track. Ms. Contos described that location as the site of a proposed "supercolumn" for the buildings contemplated by the 2018 Designs. Any column built at the location of Column #1 would prevent subway cars from operating on the Project's storage track, and thereby interfere with the proper and safe operation of that track.

37. Mr. Gagnier also identified on cross-examination a second column, Column #5, which lies within the clearance corridor of the Third Spur. The Test Track Project is not using that portion of the corridor for any of the Test Track's tracks.

38. A civil engineer that B&W called at trial, Frank Vanzler, admitted that Exhibit A-31 shows another B&W column penetrating the location of the Test Track Project's mobile traction power substation. Mr. Gagnier testified that one could move the substation, but doing so would require moving electrical ducts and other infrastructure connected to the substation.

39. Exhibit A-31 depicts on Parcel 60-E-RR-5 a single emergency stairwell for the proposed B&W apartment building. Exhibit A-31 shows the exit to that stairwell as within the Permanent Easement, outside of the Clearance Corridors but inside of the safety/security fence surrounding the Test Track facilities on Parcel 60-E-RR-5. Persons leaving the emergency stairwell thus would have access to everything inside the fence, including the Project's operating tracks and their electrified third rails.

*.*.*

MDOT and MBTA's rights to build the Test Track across Parcel 60-E-RR-5 depend on the scope of the Permanent Easement. Although the easement arises under the agreed Order of Taking, the owner of a dominant estate acquired by eminent domain (here, MDOT) still bears the burden of proving the scope of its easement rights. See Westchester Assocs. v. Boston Edison Co., 47 Mass. App. Ct. 133 , 136-137 (1999) (quoting Swensen v. Marino, 306 Mass. 582 , 583 (1940), placing burden of proof on the owner of a dominant estate, acquired through a government-approved taking, to prove its use of the taken easement was "of the same 'amount and character' as authorized"). Further,

[t]he meaning and scope of an instrument of taking, so far as it affects private rights in property, is a question of law. When deciding the scope of an easement taken by eminent domain, we must consider the language of the taking order and the circumstances surrounding the taking. When the language in a taking order is unclear, the scope of the easement should be resolved in favor of freedom of the land from the servitude. The scope of the condemnor's use of the easement will be limited to the extent reasonably necessary for the purpose served by the taking, so that the landowner's right to use the easement area is as great as possible while remaining reasonably consistent with the purpose of the taking.

. . .

If the condemnor takes an easement, the [condemnee] owner retains title to the land in fee and has the right to make any use of it that does not interfere with the public use.

General Hosp. Corp. v. Massachusetts Bay Transp. Auth., 423 Mass. 759 , 764-765 (1996)

(citations and footnote omitted).

The Court thus begins its analysis with the language of the agreed Order of Taking. The Order provides that the Permanent Easement "(i) shall be used for railroad purposes only, . . . and (iii) shall be subject to the rights of the owner of the underlying fee as hereinafter provided." Order of Taking at 26. The Order also provides this:

Said railroad easements are acquired in limited vertical dimension only, said area being limited to a height of 20'6" above the top of the rails to be placed thereon. Included in the easements, however, is the unlimited right to utilize the air rights above 20'6" for twelve (12) years following the date of recording of this taking. Thereafter, the use of said easements shall be subject to the rights of the owner of the air rights so reserved to use the area subject to the easements as reasonably may be required, subject to the approval of the party or parties having the benefit of the easements, for access to and to support the uses of the air rights.

Id. at 27-28 (emphasis added). It's undisputed that twelve years have passed since the recording of the Order, and hence MDOT's use of the Permanent Easement is now "subject to the rights of the owner of the air rights as reserved" - here, B&W - "to use the area subject to the [Permanent Easement] as reasonably may be required, subject to the approval of [MDOT], for access to and to support the uses of the air rights."

In their motions for summary judgment in this case, MDOT and the MBTA argued that notwithstanding the indented paragraph quoted immediately above, under Massachusetts law, any easement granted or taken for "railroad purposes" is exclusive, and permits no construction within the easement by the holder of the servient estate. MDOT and the MBTA cited two Massachusetts cases for that proposition. The first is Hazen v. Boston & M.R.R., 68 Mass. (2 Gray) 574 (1854). There Nathan Hazen brought a claim of trespass against the Boston & Maine Railroad. The Boston & Maine had obtained by eminent domain an easement across Hazen's property, to extend a railroad line. At the time, a state statute required railroad companies to file with a county's commissioners a precise description of the location of all railroad lines within that county. But the line the Boston & Maine built across Hazen's property was outside of the location the Boston & Maine had filed with the Essex county commissioners. The trial court concluded, and the Supreme Judicial Court agreed, that the Boston & Maine had taken only the "as-filed" easement across Hazen's land, and having built outside of the easement, the railroad was a trespasser.

The Boston & Maine argued that the court should treat the "as constructed" railroad line as evidence of what the railroad intended to take, and resolve the title dispute in a way that was consistent with the Boston & Maine's intentions. It's in that context the Hazen Court observed that

[t]he necessity for [the statutory location-filing requirement], and the object and purpose of it, are very plain. The right acquired by the corporation, though technically an easement, yet requires for its enjoyment a use of the land, permanent in its nature, and practically exclusive. The filing of the location is the act of taking the land. The location, when so filed, constitutes the written, permanent, record evidence of the land taken. It sets off by metes and bounds the land subjected to the servitude. It is conclusive upon the corporation and the landowner. It is the evidence, the only permanent evidence, of what the one has been permitted to take, and the other compelled to relinquish.

Id. at 580 (italics added, citation omitted).

MDOT and the MBTA hang their argument for the exclusivity of all railroad easements in the Commonwealth on the italicized sentence above. That sentence is dicta: remove it from its original paragraph and the Hazen Court's holding (which had nothing to do with easement law, or the rights of dominant or servient owners in easements) is the same. But even if the italicized sentence were critical to Hazen's holding, MDOT and the MBTA overlook a key adverb and a key bit of context in Hazen. The adverb is "practically." Hazen doesn't say that railroad easements are "exclusive"; they are "practically< exclusive." And the key contextual fact is this: Hazen involved an easement for the railbed of a railroad. It's easy to imagine the "practical" difficulties in building things within a railway's operating tracks, and as will be seen later, that practical problem is present in this case. Those difficulties are less apparent where, as is also true in this case, a railroad operator's easement encompasses more than clearance corridors for active railroad tracks.

The second Massachusetts case that MDOT and the MBTA cited at summary judgment, New York Cent. & H.R.R. Co. v. Chelsea, 213 Mass. 40 (1912), is to the same effect as Hazen. To MDOT and the MBTA's credit, Chelsea involves a question of easement law (what acts constitute abandonment of a railroad easement?), but Chelsea qualifies its characterization of railroad easements even more than Hazen: a taken railroad location, "though technically an easement, may require for its enjoyment permanent and practically exclusive use of the land." Id. at 45 (emphasis added). Chelsea also follows that statement with this quotation from May v. New England R. Co., 171 Mass. 367 , 369 (1898) (citations omitted): "Where land is taken for a railroad, the original owner retains all his rights which are consistent with the full enjoyment of the easement acquired by the railroad company. The two rights exist together, and the railroad company is not legally injured by any use of the land by the owner which does not interfere with the easement taken."

Rather than holding that railroad easements are absolutely exclusive of the servient owner's rights to build within them, Hazen and Chelsea are consistent with the Supreme Judicial Court's more modern treatment of allegedly exclusive rights of way. The question of whether the dominant owner of a right of way can prevent encroachments by the way's servient owner "depends on the facts and circumstances in a given case." Martin v. Simmons Props., LLC, 467 Mass. 1 , 14 (2014). Putting Martin together with General Hosp., the Court must look at the facts and circumstances surrounding the 1991 settlement documents to determine to what extent MDOT may prevent B&W from building things within the Permanent Easement.

Having rejected MDOT and the MBTA's exclusivity arguments, the Court returns to the language of the agreed Order of Taking. It states that MDOT's easement rights are "subject to the rights of the owner of the air rights so reserved to use the area subject to the [Permanent Easement] as reasonably may be required, subject to the approval of [MDOT], for access to and to support the uses of the air rights." Order of Taking at 27-28. That language forces the Court, consistent with General Hosp., to look beyond the Order of Taking to the circumstances surrounding the Order. Those circumstances (particular those reflected in the terms of the FSA and the Air Rights Agreement) show that the parties understood that their rights and obligations

changed depending on the location with the Permanent Easement and the dominant owner's activities in that location.

The Court starts with the areas in which MDOT has the greatest powers: the "clearance corridors" surrounding the "rail tracks" shown on the Permanent Rail Yard Plan, to a height of 20'6" above the rails for those tracks. This decision will call that three-dimensional space the "Planned Clearance Corridors." Within the Planned Clearance Corridors, so long as the dominant owner is using them for railroad purposes, the servient owner has the right to build things "only at such locations and with such dimensions and clearances as shall not in the judgment of the Chief Engineer of Conrail interfere with the proper and safe operation of the railroad of Conrail . . . ." Air Rights Agreement, Exhibit One at §1.

The Court now turns to the areas over which MDOT has the least powers: the "surface and subsurface" of the Overbuild Corridors. While the Overbuild Corridors aren't within the Permanent Easement, given their proximity to the Permanent Easements and the servient owner's needs for access to the Overbuild Corridors, the parties to the 1991 settlement decided that they needed rules governing construction in the Overbuild Corridors. Those rules nevertheless those rules favor the owner of the servient estate under the Permanent Easements. Section 1 of Exhibit One to the Air Rights Agreement provides that the servient owner has "the right and privilege to locate, construct, and install as well as maintain and renew" in the Overbuild Corridors "suitable and necessary walls, columns, footings, foundations, drainage, communications and utility systems and related support structures necessary for the support of any future building or buildings and related facilities erected in" the Contos family's reserved air rights. Id. The servient owner's only obligations to the dominant owner with respect to construction in the Overbuild Corridors are these:

* To submit to the dominant owner's Chief Engineer the servient owner's "preliminary and final plans and specifications" for such work. "The approval of the Chief Engineer . . . shall not be unduly delayed or unreasonably withheld." Moreover, with respect to work in the Overbuild Corridors, the dominant owner "shall grant approval therefor, provided such construction and installations shall not unreasonably interfere with the operation and maintenance of the BTRT and the Permanent Rail Yard . . . . Such construction and installations shall be approved by the Chief Engineer . . . before construction is commenced." Id. at §3.

* To perform "construction, maintenance, repair and renewal work located within . . . the Permanent Rail Yard Easement Area, or proximate thereto, . . . at such time and in such manner as will be satisfactory to the Chief Engineer of Conrail so as not to unreasonably interfere with or endanger the railroad operations of Conrail." Id.

* To protect, and not interfere with, railroad operations during and after construction. See id. at §§4, 23.

That leaves those areas above and within the Permanent Easement that are outside of the Planned Clearance Corridors (including the areas below the surface of the Planned Clearance Corridors), which this decision will call the "Other Areas." The 1991 settlement documents provide the following as to the Other Areas:

* The dominant owner may not place in those Areas (or anywhere else in the Permanent Easement, for that matter) "more than two (2) rail yard storage tracks with vertical clearances of 20'6" as set forth in Part IV, Section A(4) . . . and one (1) gravel access road, all as shown on [the] Permanent Rail Yard Plan." FSA, §IV.A.2.

* "The permanent yard track layout on the Permanent Easements shall be in accordance with the Permanent Rail Yard Plan . . . ." The dominant owner may make "[m]odifications to the Permanent Rail Yard Plan" only "if either (i) the modified track layout on the Permanent Easement remains within the [Planned Clearance Corridors] and in no material way adversely impacts the interests of Contos, or (ii) the modified track layout is approved in writing by Contos in consultation with Conrail." FSA, §IV.C.

* Within both the Planned Clearance Corridors and the Other Areas, the dominant owner "shall have the right to construct and maintain [the Permanent Rail Yard] and all other necessary appurtenant facilities, including, but not limited to, signal, switching and lighting equipment, conduits and drain lines for the use by Conrail." Air Rights Agreement, Exhibit One at §2.

* Within both the Planned Clearance Corridors and the Other Areas, the dominant owner was to operate "the BTRT and the Permanent Rail Yard" so as not to "unreasonably disturb or affect any future building or buildings or related support structures to be constructed . . . above the BTRT or the Permanent Rail Yard Easement Area," although the servient owner agrees "that the normal noise, vibration and exhaust associated with rail operations" do not constitute such a disturbance. Id.

* The servient owner "shall have the right to construct, install and maintain any drainage, communications and utility systems necessary to service any future building or buildings erected in the . . . air space below the [20'6"] horizontal plane and outside the [Overbuild C]orridors only at such locations and with such dimensions and clearances as shall not in the judgment of the Chief Engineer . . . interfere with the proper and safe operation of the railroad of Conrail . . . ." Air Rights Agreement, Exhibit One at §1.

* As with the case of construction in the Overbuild Corridors, the servient owner is obligated to provide to the Chief Engineer preliminary and final plans and specifications for work within the Other Areas. But the settlement documents don't obligate the Chief Engineer to approve such work in the manner he or she would have to approve that work were it to occur in the Overbuild Corridors. Instead, the test for approval of work in the Other Areas is whether, in the "informed and reasonable" opinion of the Chief Engineer, see Air Rights Agreement, Exhibit One at §23, the servient owner's activities will "not unreasonably interfere with, disrupt or impede the construction, maintenance or use by Conrail . . . of the Permanent Easement Area" for its allowed purposes. FSA, Part IV.A.5.

* As with construction in the Overbuild Corridors, the servient owner must take precautions during and after construction in the Other Areas, plus indemnify the dominant owner for certain losses. See Air Rights Agreement, Exhibit One at §§3, 4, 9 and 23.

MDOT and the MBTA argued at summary judgment that, apart from what Massachusetts common law regarding railroad easements dictates, the FSA and the Air Rights Agreement prohibit the servient owner from installing any columns or other support features anywhere on the surface of the Permanent Easement, including the Other Areas. The Court disagrees, for four reasons:

* No prohibition on surface construction expressly appears in the FSA, the Air Rights Agreement or the agreed Order of Taking.

* The claimed prohibition is inconsistent with Part IV.A.5 of the FSA, which gives the servient owner "the right to enter into the Permanent Easement Area for such purposes . . . or to take other actions, including, without limitation, construction activities related to the Contos Development described in Part VI, Section A " The servient owner's ability to exercise that right turns on only two things: (1) prior notice to the dominant owner, and (2) the Chief Engineer's determination that "said activities do not unreasonably interfere with, disrupt or impede the construction, maintenance or use by Conrail (pursuant to Part IV, Section B) . . . of the Permanent Easement Area." FSA, Part IV.A.5; Air Rights Agreement, Exhibit One at §23.

* At least three other provisions of the FSA refer to the servient owner's activities and improvements "upon" the Permanent Easement Area. See FSA, Part IV(A)(5) (indemnity provision); id. at Part IV(D)(2) (indemnity provision); id. at Part IV(E) (tax-liability provision). The parties wouldn't have needed to protect the dominant owner from improvements "upon" the Permanent Easement Area if the settlement had prohibited such improvements. See Estes v. DeMello, 61 Mass. App. Ct. 638 , 642 (2004), quoting Jacobs v. United States Fid. & Guar. Co., 417 Mass. 75 , 77 (1994) (interpretation of an easement by grant that gives "'reasonable meaning'" to all of the grant's provisions "'is to be preferred to one which leaves a part useless or inexplicable'").

* If the first three points leave any doubts as to how the settlement documents treat the rights of the servient owner to build upon the Other Areas, that doubt is to be resolved in the servient owner's favor. See General Hosp., 423 Mass. at 764.

In light of its analysis of how the settlement documents treat the Planned Clearance Corridors, the Overbuild Corridors, and the Other Areas, the Court directed the parties to proceed to trial on these issues:

1. Will the Test Track require, within the meaning of §IV.C of the FSA, a "modification" to the Permanent Rail Yard Plan?

2. If the answer to question 1 is yes, will any "modified track layout" associated with the modification remain within the Planned Clearance Corridors, as set forth in §IV.C(i) of the FSA?

3. If the answer to question 2 is yes, will the modified track layout "in no material way adversely impact[] the interest[]" of B&W, as that phrase appears in §IV.C(i) of the FSA? [Note 5]

The Court has found that the Test Track Project entails several "modifications" to the Permanent Rail Yard Plan. None of the Test Track facilities appears on the Permanent Rail Yard Plan, and the Test Track's two tracks don't match the routes of any of the tracks shown on the Permanent Rail Yard Plan. See Finding 27. That said, MDOT and the MBTA have proven that the Test Track's "modified track layout" remains within the Planned Clearance Corridors. See Finding 29. [Note 6]

The case thus boils down to the third question for trial, whether the Test Track Project's modified track layout "in no material way adversely impacts the interest[]" of B&W. The Court holds that MDOT and the MBTA have proven that the modified track layout in no material way adversely "impacts" B&W's interests. It's undisputed that no part of the Test Track Project has been or will be built within the Overbuild Corridors, and no part of the Project will exceed the 20'6" elevation above the MBTA's tracks on Parcel 60-E-RR-5. One thus can't presume that the Test Track Project will adversely affect B&W's interests. Instead, evaluating the Project's effects upon B&W's interests requires knowing what B&W thought it could build. Under the settlement documents, it's B&W's obligation to prepare its own development plans, and to initiate inquiries pertaining to such plans. See Air Rights Agreement, Exhibit One at §§3, 7 and

16. Provided that MDOT's tracks stay within the Planned Clearance Corridors (or, if they don't, provided that any track modifications comply with Part IV.C), the settlement documents don't obligate MDOT to speculate how B&W might develop its air rights, and design railroad facilities within the Permanent Easement accordingly. Similarly, in the absence of approved plans for development of B&W's air rights, the settlement documents don't require MDOT to coordinate with B&W with respect to MDOT's construction activities within Parcel 60-E-RR-5.

The last development plans that B&W presented to MDOT and the MBTA are the 2018 Designs. The fatal flaw in those Designs is that they call for installation of a support column (which Anastasia Contos described as a "supercolumn") within a Planned Clearance Corridor. The MBTA has built (or will be building) in that Corridor one of the Test Track Project's tracks. See Finding 36. As noted earlier, MDOT's powers under the settlement documents are at their greatest (and B&W's interests are so low as not to be material) when it comes to a structure that the servient owner wants to build in a Planned Clearance Corridor, if that structure interferes with railroad operations. Putting a column through an operating railbed doesn't just "interfere" with railroad operations: it literally stops them in their tracks. B&W thus had no right to build what it presented in the 2018 Designs. And since B&W had no right to build what's shown in the 2018 Designs, MDOT and the MBTA's Test Track-related modified track layout does not in any material way "impact[]" B&W's interests in developing Parcel 60-E-RR-5.

The Court ends its conclusions of law there. [Note 7] At page 13 of its trial brief, B&W acknowledged that it isn't asking the Court to decide what B&W can build on Parcel 60-E-RR-5.

That depends on a myriad of development-specific questions, many of which are likely beyond the Court's ken. Some or all of the MBTA facilities on the Parcel, outside of the Planned Clearance Corridors, could be relocated; the settlement documents provide guidance as to how that can be accomplished, and at whose expense. [Note 8] Likewise, now that the Test Track Project is largely built, it's conceivable that the MBTA has a better sense of when it will be testing subway cars, and hence it could be easier for the parties to arrange for access to some or all of Parcel 60- E-RR-5 without anyone hurting themselves. (The settlement documents always anticipated that the dominant and servient owners would have to work around the dominant owner's railroad operations.)

The history of the uses of Parcel 60-E-RR-5 also has been one of change. The dominant owner of the easement across Parcel 60-E-RR-5, MDOT, is not a private railroad company. The facilities that occupy the Parcel aren't part of what the parties to the 1991 settlement envisioned as the Permanent Rail Yard. No one needs a "gravel access road" to serve the (nonexistent) Permanent Rail Yard's storage tracks. The eastern end of the Planned Clearance Corridor that's associated with the Third Spur appears to lead to nowhere. And the MBTA's chief of the Test Track Project testified that testing of Red Line cars likely will end in 2024. As of the time of trial, the MBTA had no plans for Parcel 60-E-RR-5 beyond 2024.

The Court will end this Decision, however, with the following observation. In the early 1990s, the Commonwealth had the chance to take a fee interest in Parcel 60-E-RR-5. Had it done so, the Commonwealth (and later Conrail, and now MDOT) likely would have enjoyed complete control over the Parcel. But the Commonwealth didn't take a fee interest. Instead, it opted to take easements over Parcel 60-E-RR-5, and in the bargain agreed to let the servient owners, the Contos family, develop their air rights once the Big Dig was built. The parties to the 1991 settlement documents understood that development of the Contos air rights was going to require communication and various levels of cooperation among the parties.

The Court credits the testimony of B&W's witnesses that their attempts to get information from MDOT and the MBTA about the Test Track Project between June 2017 and February 2018, and even thereafter - information that B&W needed to prepare its air-rights development plans - left B&W wondering whether MDOT and MBTA were acting in accordance with the Massachusetts implied covenant of good faith and fair dealing. The leading case describing the covenant, Anthony's Pier Four, Inc. v. HBC Assocs., 411 Mass. 451 (1991), arose curiously enough in the context of two other Seaport District developments, just prior to the events recounted in this decision. HBC Associates was developing the Fan Pier, and Anthony's was developing abutting Pier Four. The two entered into a development-coordination agreement that gave Anthony's limited rights of approval over any changes to HBC's plans.

Four years into the agreement, Anthony's withheld a discretionary approval that led to HBC halting its work on Fan Pier. The trial court found that Anthony's motive in withholding the approval was to win concessions from HBC on issues that were unrelated to the changes in HBC's plans. See id. at 472-473.

The Supreme Judicial Court used Anthony's Pier Four as a reminder that in Massachusetts, "[e]very contract implies good faith and fair dealing between the parties to it.' The implied covenant of good faith and fair dealing provides 'that neither party shall do anything that will have the effect of destroying or injuring the right of the other party to receive the fruits of the contract . . . .'" Id. at 471-472 (citations omitted), quoting Warner Ins. Co. v. Commissioner of Ins., 406 Mass. 354 , 362 n.9 (1990), and Drucker v. Roland Wm. Jutras Assocs., 370 Mass. 383 , 385 (1976). The Court upheld the trial court's ruling that Anthony's pretextual disapproval of HBC's plan changes "destroyed or injured HBC's right to receive the fruits of the [parties' development] contract and thus violated the implied covenant." Anthony's Pier Four, 411 Mass. at 472.

The implied covenant of good faith and fair dealing applies to all Massachusetts contracts, including those to which Commonwealth and its departments are a party. See, for example, A.L. Prime Energy Consultant, Inc. v. Massachusetts Bay Transp. Auth'y, 479 Mass. 419 , 434 (2018). The parties didn't put to this Court the question of whether MDOT performed its duties under the 1991 settlement documents in accordance with the implied covenant. This Court's decision on the issue that is before this Court, whether MDOT and the MBTA may build the Test Track Project on Parcel 60-E-RR-5, doesn't turn on implied covenant issues either. And there's no evidence in the trial record that MDOT or the MBTA schemed to withhold information from B&W so as to thwart B&W's development efforts, or to extract benefits from B&W that should have been negotiated in 1991. Nevertheless, B&W's experience in prying information from the responsible departments and authorities, so as to exercise its bargained-for rights to develop the airspace above the Permanent Easement, should serve as a caution to those whose development plans depend on certain agencies abiding by their agreements to cooperate.

Judgment to enter accordingly.

B&W SECOND LLC vs. MASSACHUSETTS BAY TRANSPORTATION AUTHORITY, MASSACHUSETTS DEPARTMENT OF TRANSPORTATION, and CSX TRANSPORTATION, INC.

B&W SECOND LLC vs. MASSACHUSETTS BAY TRANSPORTATION AUTHORITY, MASSACHUSETTS DEPARTMENT OF TRANSPORTATION, and CSX TRANSPORTATION, INC.