Introduction

This case is a petition, filed by Gordon Tyra and the late Edwin Tyra, to register a parcel of land in Edgartown. Broadly speaking, such petitions involve three issues: (1) the petitioners title to the land whose registration is sought, (2) the boundaries of that land, and (3) its encumbrances, if any. Encumbrances include not only mortgages, restrictions, and the like, but also others rights of use or access across the property (easements). Once title is registered it binds the land and quiets title thereto and is conclusive upon and against all persons, including the commonwealth, whether mentioned by name in the complaint, notice or citation, or included in the general description to all whom it may concern. G.L. c. 185, §45. With only narrow exceptions, every plaintiff receiving a certificate of title in pursuance of a judgment of registration, and every subsequent purchaser of registered land taking a certificate of title for value and in good faith, shall hold the same free from all encumbrances except those noted on the certificate. G.L. c. 185, §46. No title to registered land, or easement or other right therein, in derogation of the title of the registered owner, shall be acquired by prescription or adverse possession. Nor shall a right of way by necessity be implied under a conveyance of registered land. G.L. c. 185, §53.

Every registration petition is accompanied by a plan of the land sought to be registered, and those plans must show, among other things, the property boundary lines, [Note 1] all observable features that may have a bearing on the determination of property boundary lines or title lines such as boundary monuments, walls, fences, buildings, water bodies, limits of occupation, roads, cart paths, encroachments and easements, [Note 2] and all actual facts existing on the ground (e.g., pathways) [Note 3] whether or not the plaintiff believes they reflect any rights in others. If the plaintiff denies that such a pathway reflects easement rights in others, he must specifically so state in his petition and request a corresponding declaration from the court. If the court declares that there is no such easement, it will not appear on the certificate of titles encumbrance sheet or on the final, approved registration plan.

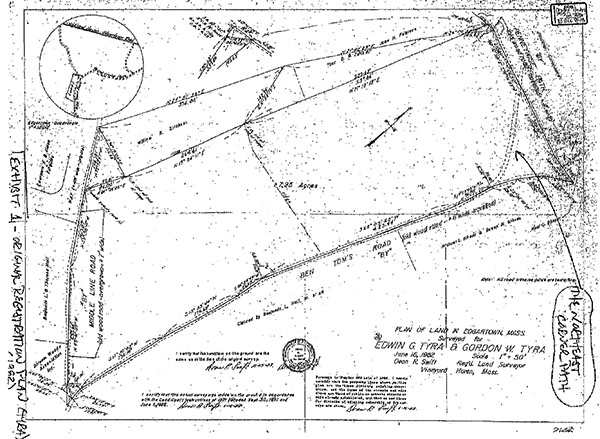

The plan originally submitted in this case, a copy of which is attached as Ex. 1, [Note 4] shows a rectangular parcel, approximately 7.25 acres in size, bounded by Penneywise Path to the north, [Note 5] Ben Toms Road to the east, [Note 6] Middle Line Road to the south, [Note 7] and abutting two other properties to the west. [Note 8] The petition requested registration of this parcel subject to rights of persons entitled or who may become entitled to use the portions of Penneywise Path, Ben Toms Road and Middle Line Road which are located within said land and, in a supplement, den[ied] the existence of rights in any and all persons to use or pass over the path delineated on said plan

and shown crossing said land from Ben Toms Road to Penneywise Path at the northeasterly corner of said land, and petitioned the Court to eliminate said path from the Plan to accompany the decree of registration. Petition, Supplement to ¶ 4.

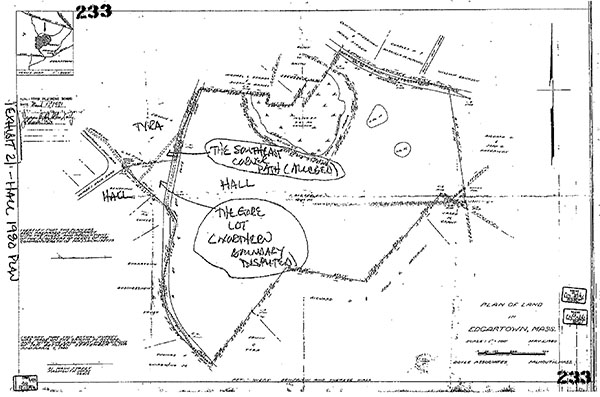

On December 7, 1983, the Court appointed attorney Philip J. Norton to conduct a title examination for the property at issue. [Note 9] Attorney Norton filed his report on February 13, 1991. In the course of his research, Attorney Norton noticed that the deeds to the Tyra parcel described the propertys southern boundary as being by the land of Nicholas Norton, not Middle Line Road as shown on the Tyras 1982 plan. He then researched the deeds of properties abutting the Tyra parcel and discovered a 1796 deed from John Coffin (a predecessor owner of the Tyra parcel) to William Vinson conveying a one acre lot of land lying in a gore. [Note 10] Deed, John Coffin to William Vinson (June 17, 1796). He also found a 1980 survey plan, prepared for defendants Benjamin and Therese Hall and recorded at the Registry in Case File #233, [Note 11] showing a gore-shaped lot between the Tyra parcel and Middle Line Road and a possible claim by the Halls to ownership of that gore. A copy of that plan is attached as Ex. 2. In his Certificate of Opinion, Attorney Norton determined that the Tyras had good title to their parcel, proper for registration, except, perhaps, for [a] small portion in [the] southeast corner (i.e., the gore lot its location, as yet, undetermined). Norton Report, Sheet No. 1.

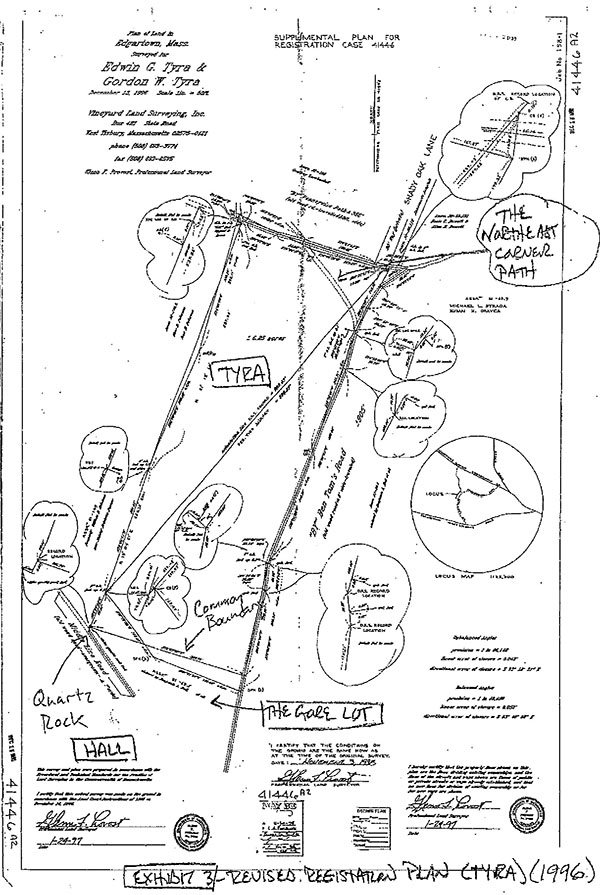

Notice of the Tyras registration petition was given to all abutting landowners, as well as published generally to all whom it may concern. G.L. c. 185, §45. Only defendant Benjamin Hall and his late wife Therese filed a response. In that response, the Halls asserted ownership of the gore parcel and thus challenged the Tyras southern boundary as shown on the original registration plan (Ex. 1). In response, the Tyras moved to withdraw the gore from their registration petition and prepared a revised plan, limiting their request for registration to the remainder of the property. [Note 12] That revised plan (Ex. 3) showed a new southern boundary, beginning at a white quartz rock and extending in a straight line from the side of Middle Line Road to Ben Toms Road. Plan of Land in Edgartown, Mass., Surveyed for Edwin G. Tyra and Gordon W. Tyra (Dec. 13, 1996) (hereafter, the 1996 Plan). The basis for this newly drawn boundary is discussed below.

On July 19, 2007, this Court (Lombardi, J.) allowed the Tyras motion, substituted the description of the property found in the original petition with the description contained in the Tyras motion, and ordered that the 1996 plan supersede the 1982 plan and serve as the operative plan for all further proceedings in this case.

At a case-structuring conference held to frame the issues and focus discovery and trial preparation, the Halls stipulated that their only issues are (1) the location of the common boundary line [between the Tyra parcel and the gore lot, see Ex. 3] (and title to the land that boundary line dispute puts in issue), [Note 13] and (2) the existence and location of various alleged ways across the plaintiff's property and their rights, if any, to use those ways. [Note 14] Notice of Docket Entry (Aug. 29, 2008).

The case was tried before me, jury-waived. Based on the testimony and exhibits admitted into evidence at trial, my assessment of the credibility, weight, and inferences to be drawn from that evidence, and as more fully set forth below, I find that the Tyras (1) have established good title, proper for registration, to the land shown on the 1996 plan (Ex. 3), and (2) have met their burden of showing that there are no rights of access or use in others to the path crossing the northeast corner of the parcel, the alleged path crossing the southeast corner, or any other paths across the property. Those paths shall be eliminated from the plan that will accompany the decree of registration, and the registration shall be subject only to the rights of persons entitled, or who may become entitled, to use Penneywise Path, Ben Toms Road and Middle Line Road as located on the 1996 plan.

Facts

The parties respective contentions were presented through the testimony of their witnesses and the various deeds, plans and other documents admitted into evidence at trial. The Tyras witnesses were Philip Norton, a real estate attorney appointed by the Land Court to examine the Tyras title, and Glenn Provost, a registered land surveyor who prepared the 1996 supplemental plan for the Tyra parcel. The Halls witnesses were Donna Goodale, a lay title abstractor (not an attorney) who has never certified a title, and defendant Benjamin Hall himself, who has experience as an owner of real estate on Marthas Vineyard but no formal training in title examination or land surveying and thus was taken as a fact witness only. The Halls did not present a title examiner or land surveyor of their own as witnesses in this case.

These are the facts as I find them after trial.

Attorney Norton is a real estate attorney who has practiced in the Commonwealth since 1964. Approximately 90 to 95 percent of his practice consists of real estate work for properties on Marthas Vineyard, where he regularly reviews and certifies title and acts as title agent for First American Title Company. Most of this work involves research at the Dukes County Registry of Deeds. In a typical year, Attorney Norton will examine approximately 100 titles. He was first appointed by the Land Court to examine titles in the 1970s and 1980s, and has since acted as a title examiner for the Court somewhere between 20 to 30 times.

Attorney Norton was appointed as the Land Court title examiner for the Tyras registration petition on December 7, 1983, and performed those tasks in collaboration with John Larsen, a title abstractor whose work he directed and supervised. As attested by Attorney Norton and confirmed by this Court in its independent review of the deeds and other evidence in this case, the Tyras chain of title is as follows.

The Tyras title came by deed from Helen Tyra and Gordon Shurtleff dated May 5, 1967, recorded at the Dukes County Registry of Deeds in Book 266, Page 304. Helen Tyra and Gordon Shurtleff obtained their title from the estate of their father, Charles Shurtleff, who died testate on October 22, 1964. Charles Shurtleffs title came by deed from Mary Shurtleff, Mabel Boylston, Elsie Norton and Alice Shurtleff dated November 16, 1907, recorded at the Registry in Book 114, Page 420. Mary Shurtleff, Mabel Boylston, Elsie Norton, Alice Shurtleff, and Charles Shurtleff received their title on November 29, 1906 from the estate of their father, Charles Frederick Shurtleff, as his heirs at law. Charles Frederick Shurtleff received his title by deed from James Huxford, George Jernegan and John Coffin dated September 8, 1879, recorded at the Registry in Book 66, Page 145. This 1879 deed was Attorney Nortons commencement deed which marked the starting point for his abstract of title to the property. As he testified, under title examination standards, absent a demonstrated need to do so, an examiner does not need to go back to the Louisiana Purchase

50 years is good. [Note 15] The 1879 deed was, in his view, a comfortable starting point for the examination.

The Halls hired a lay title abstractor, Donna Goodale, to search for earlier deeds in the chain, and offered the deeds she found at trial. Ms. Goodale works under the direction and supervision of local attorneys, locating and gathering documents at the Registry for them to review, but she herself is not an attorney, has no formal training in title searches (only on the job experience as a paralegal), and has never certified title. She is not a surveyor and has no training or experience as a surveyor. I thus did not find her competent to opine on title matters, to give opinions on the meaning of deeds, or to give opinions on the physical location of the land described in those deeds, and the Halls did not call any expert witnesses on these matters. The links she attempted to draw, deed to deed, required such expert testimony to have any evidentiary significance. Her testimony was thus limited to a description of her search, not its validity or meaning. There was thus no competent evidence whether the deeds she found are, in fact, related to the Tyra parcel and, if so, how and to what extent. They thus did not call Attorney Nortons title search and conclusions into question, and I find that his 1879 starting point was sufficient.

The registration plans submitted by the Tyras show a pathway crossing the northeast corner of the parcel starting at Ben Toms Road and continuing to Penneywise Path (hereafter, the northeast corner path). See Exs. 1 & 3. It is shown on those plans because there is physical evidence of such a path on the ground [Note 16] and, because the Tyras have requested it be excluded from the encumbrances on their title and stricken from the final registration plan (they contend that no one else has a right to use it), the court is required to consider its status in these proceedings. Notice of these requests was given to all abutting landowners, as well as published generally to all whom it may concern, and only the Halls oppose them, claiming the right to use that path. The Halls also claim rights in another path, not shown on the Tyras plans, which allegedly also exists and crosses the southeast corner of the Tyra parcel. This other pathway is depicted on the 1980 survey recorded by the Halls in Registry Case File #233 (Ex. 2, attached) (hereafter, the southeast corner path). None of the deeds in the Tyra chain (the burdened property, if there was such a burden) contain or reference any rights in others to the use of those paths, or to any other path or trail across that land. [Note 17], [Note 18] None of the deeds to any other properties show the benefit of such pathways. [Note 19] I thus find that there is no express easement over any pathway crossing any part of the Tyras parcel that benefits the Halls, the Halls property, or any other person or property. The evidence indicated that the Tyra parcel was primarily a woodlot, and the paths across that land were likely created and used by its owners to access, cut and remove wood not as a means of access or use by others. I so find.

With title to the parcel thus established, the question turns to its on the ground location. It is described in the1879 deed (which also conveyed other properties) as:

Also one other wood lot situated as aforesaid, Commencing near the spot where once lived Martin Vincent, now deceased, and by the Penneywise road; then Southerly by land of Clement Pease to land of Nicholas Norton; then by land of said Nicholas, Easterly, by a way to the Penneywise road and by said road to the place of beginning.

All subsequent conveyances of the parcel followed this description. Since it lacks any distances or references to specific monuments other than abutting roads and properties, Attorney Norton turned to the deeds and plans for those abutting properties, using them like a jigsaw puzzle to establish the Tyra parcels boundaries and determine its location on the ground. This is standard practice, and the proper approach. [Note 20]

Attorney Norton began by locating a survey plan referenced in a deed from Susan Graves to Michael Strada dated December 15, 1982, recorded in Book 397, Page 853, that aligned with the Tyra parcels northeastern boundary. A deed from Bruce Page to Thor Peterson and Joan Peterson dated June 11, 1976, recorded in Book 335, Page 277, referenced the land of Charles Shurtleff (the Tyras predecessor in interest) as an abutter, thereby confirming the Tyras northwestern boundary. [Note 21] The Peterson deed describes that lot as abutting the land of Arthur Vincent. This reference matched the deed for the Erickson property to the south, which states that the Erickson lot had once been owned by Arthur Vincent. See Deed, Doris Belisle and Madelyn Mitchell to Shirley Erickson and Carl Erickson dated Dec. 6, 1971, recorded in Book 314, Page 45. Having located the Erickson property to the south of the Peterson lot, Attorney Norton thus established the Tyra parcels southwestern boundary. The remaining boundaries consisted of Penneywise Path to the north and, to the east, Attorney Norton determined that the way leading easterly to Penneywise Path, referenced in the Tyra deeds, was Ben Toms Road. [Note 22] I concur with these conclusions and so find, and specifically find that Penneywise Path and Ben Toms Road are in the locations shown on the 1996 plan (Ex. 3). [Note 23]

This left the parcels southern boundary, about which Attorney Norton had questions. It is shown on the Tyras originally-submitted registration plan (the1982 plan [Ex. 1]) as Middle Line Road. The deeds for the Tyra parcel did not mention Middle Line Road as a southern boundary, but instead referred to the land of Nicholas Norton. This led Attorney Norton to believe there was a gore somewhere to the south, to which the Tyras might not have title. This belief was confirmed when Attorney Norton researched the title to the Erickson property, which abuts the Tyra parcels southwestern boundary, and found other references to the land of Nicholas Norton.

When Attorney Norton examined the title of defendants Benjamin and Therese Hall, who abut the southeastern boundary of the Tyra parcel on the opposite side of Ben Toms Road, he discovered a plan they had recorded which includes a gore-shaped lot to the south of the Tyra parcel as part of the property they claim to be theirs. See Ex. 2. Attorney Norton believed that plan showed a likely representation of the gore lots general shape and location, although its precise location would need to be determined. In addition to the Halls plan, the deed for the Hall property also indicated to Attorney Norton that the Halls might have an ownership interest in the gore lot. [Note 24] Attorney Norton found no other claims of ownership to the Tyra parcel aside from the gore lot claimed by the Halls.

In connection with his research into the gore lot, most specifically his attempt to see where it physically was located, Attorney Norton ran its title back to a 1796 deed from John Coffin to William Vinson. This deed described the gore lot as:

Beginning at a stake and stone [Note 25] set in the ground, by the side of the land belonging to Jonathan Pease, and is the bound between the said John and said Williams land, from said stake and stone about Southeast by said Williams land until it comes to the Northwest side of a cartway to a stone set in the ground, from thence about Northeast by the side of said cartway about thirteen rods to a stone set in the ground, or so far as to make one Acre of Land, and from thence Northwesterly to the first mentioned stake and stone by the side of the said Jonathans land, the said Acre lying in a gore.

Deed, John Coffin to William Vinson dated June 17, 1796, recorded in Book 14, Page 73 (the 1796 deed). In Attorney Nortons opinion, based on all the work he has done, the Tyras have good title, proper for registration, to all of the land shown on the 1982 plan except for the gore lot. I concur and so find. The question thus turns to the location of the boundary between the gore lot and the remaining land.

In 1995, following Attorney Nortons report, the Tyras contacted Glenn Provost, a registered land surveyor on Marthas Vineyard, about making changes to the 1982 survey plan prepared by Dean Swift. [Note 26] Mr. Provost began his career in 1968 as a surveyor apprenticed to Mr. Swift. In 1983, Mr. Provost became a registered land surveyor and started his own company, Vineyard Land Surveying. Mr. Provost does the bulk of his workapproximately 99 percenton Marthas Vineyard. Over the course of his career, he has appeared as a survey witness in Superior Court and Land Court proceedings approximately 20 times.

Since his work in this case involved registered land, Mr. Provost began by speaking with the late Charles Forbush, who was then an engineer at the Land Court, about how to proceed with developing a new plan for the Tyras. Mr. Provosts task was to take the 1982 plan and sever off the gore from the Tyra parcel by establishing a line that would set the common boundary between the Tyras and the gore lot. This was deemed a supplemental plan to the original 1982 survey. Creating a supplemental plan was (and is) the typical practice for the Land Court when changes need to be made to a plan already filed with the court. Since Mr. Provosts task was to establish a common boundary between the gore lot and the Tyra parcel, the only deed he reviewed was the 1796 deed creating the gore lot. He also reviewed and relied upon Attorney Nortons title narrative, which I find accurately reflects the Tyras title and its antecedents. Mr. Provost did not conduct any other title research or review any other deeds for abutting properties to verify the boundaries of the Tyra parcel. I find that there was no need to do. He had no need to reinvent the wheel, particularly since, as stipulated, the only boundary line in question was the gore lot boundary and no competent, credible evidence was introduced that casts doubt on any of the other lines surveyed and set by Mr. Swift in 1982. As previously noted, the Halls did not introduce any counter-testimony from a surveyor of their own.

In preparing the supplemental survey plan (the 1996 plan, Ex. 3), Mr. Provost first performed a field traverse [Note 27] to locate and confirm that the boundaries shown on the 1982 plan were still there and were still accurate. After performing the traverse and locating the bounds that the 1982 plan showed, Mr. Provost then took an inverse, which is a calculation from bound to bound, and confirmed that the calculations were within an acceptable tolerance for a situation where one person takes the original measurements and then another person calculates those same measurements. After the measurements were taken and the field work was complete, Mr. Provost went to the Tyra parcel, walked the boundaries and saw all the bounds that Dean Swift had indicated on the 1982 plan. I find this sufficient to verify the accuracy of the 1982 survey. Again, the Halls did not offer any expert testimony to counter this.

Turning now to the common boundary line between the Tyra registration parcel and the gore lot, Mr. Provost testified that he reviewed the 1796 deed that conveyed the gore lot and relied on its description to put its boundaries on the ground. His starting point was the white quartz rock shown on both the 1982 plan and the 1996 plan, which was a distinctive marker, in the right location (by the side of the land belonging to Jonathan Pease, at the bound between that land and said William [Vinsons] land), had clearly long been there, and which he thus concluded was the beginning stone referenced in the 1796 deed (Beginning at a stake [Note 28] and stone

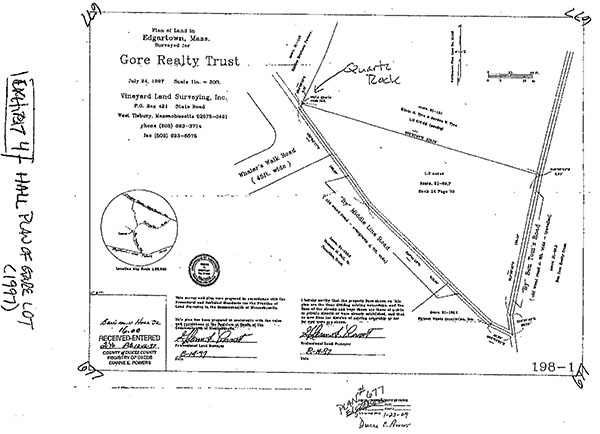

). It was also near, but did not perfectly align with, a corner boundary for the gore lot as shown on the Halls 1980 plan in Case File 233 (Ex. 2). That boundary on the Hall plan falls on the western side of Middle Line Road, while the white quartz rock used by Mr. Provost is on its eastern side. Compare Exs. 2 and 3. For these and the other reasons discussed below, Mr. Provost concluded that the white quartz rock marked the proper beginning point for the gore lot, not the large stone referenced in the Halls 1980 plan (Ex. 2). The Halls cannot credibly disagree, since they too hired Mr. Provost to survey the gore lot and adopted both the white quartz rock and the rest of Mr. Provosts survey in the plan of that lot they recorded in 1997. [Note 29] See Ex. 4.

Mr. Provost testified that, around 2000, after he had prepared the Tyras supplemental (1996) registration plan (Ex. 3) and the 1997 gore lot plan for the Halls (Ex. 4), the Halls attorney in these proceedings, Benjamin Hall Jr., approached him with a deed describing the Erickson property abutting the Tyra parcels southwestern boundary. [Note 30] This deed for the Erickson property began at a stone set in the ground by a way that leads from the Plains to the place which was formerly Simmons Vincents. Attorney Norton had testified previously that the way leading to the place formerly owned by Simmons Vincent is Middle Line Road, sometimes called Simmons Field Road. Although Mr. Provost did not rely on that deed when preparing his 1996 plan, he testified that its description was further confirmation of his conclusion that the white quartz rock was the proper boundary between the Tyra parcel, the Erickson property and the gore lot because it was set in the ground near Middle Line Road. In Mr. Provosts expert opinion, spoken as one with long experience with Marthas Vineyard and its surveying practices, the white quartz rock was the likely starting point called for in the deeds because a white quartz rock was different from other stones that are typically found in the area (i.e. it was clearly set there and not naturally occurring) and that, to him, gave it additional significance.

Starting at the white quartz rock, Mr. Provost followed the description of the 1796 deed southeast by Williams land until it comes to the Northwest side of a cartway to a stone set in the ground

. Mr. Provost interpreted this call as running along Middle Line Road, which he believed was the boundary that established Williams land referenced in the deed. He looked for the stone set in the ground by the northwest side of Ben Toms Road (the cartway referenced in the deed), but could not locate it, concluding it no longer existed. Since it was described as being by the northwest side of that road, he used that point as his reference. He then followed the next call in the deed 13 rods northeasterly by the cartway to a stone or so far as to make one Acre of Land. Again, no stone was found, but Mr. Provost felt the language or so far as to make one Acre of Land was critical to the description. [Note 31] Therefore, he went slightly more than 13 rods along Ben Toms Road until he came to a point that produced a triangle of land consisting of one acre. Thirteen rods is 214.5 feet. [Note 32] Mr. Provosts one acre point was 222.93 feet, slightly less than 8.5 feet further than 13 rods. According to Mr. Provost, this same boundary as shown on the Halls 1980 plan in Case File 233 is approximately 300 feet 80 feet beyond the point Mr. Provost set on his 1996 plan. A 300 foot line is approximately 18.5 rods which, in Mr. Provosts opinion, is a significant deviation from the 13 rods called for in the 1796 deed and is thus not correct. In contrast, his point, less than 8.5 feet further than 13 rods, was almost dead on and within an acceptable deviation. [Note 33]

Having established the three corners of the gore lot, Mr. Provost then closed the triangle by setting a common boundary line between the southern section of the Tyra registration parcel and the northern section of the gore lot. Mr. Provost relied on his calculations to set the line in a location that yielded an acre of land. He then fixed that line on the 1996 supplemental plan. See Ex. 3.

As noted above, in 1997, Mr. Provost also prepared a plan on behalf of the Halls depicting the gore lot. Ex. 4. This plan begins at the same white quartz rock and depicts the same common boundary line as that shown on the 1996 plan Mr. Provost prepared for the Tyras. Mr. Provost gave this plan to the Halls to record as they saw fit. He himself did not record that plan, but testified that when a plan is brought to the registry to be recorded, the registry will note on the plan the name of the person who brought it in. Benjamin Hall Jr.s name is written on the plan, next to a registry stamp indicating that the plan was received and entered at the Dukes County Registry of Deeds at 2:40 p.m. on October 16, 1997. See Ex. 4. [Note 34]

In an attempt to establish prescriptive rights to the northeast corner and southeast corner paths across the Tyra registration parcel, the Halls called defendant Benjamin Hall Sr. as their only witness. Mr. Hall grew up in Edgartown and has been in the real estate business since the 1960s when he began acquiring property on Marthas Vineyard. Mr. Hall claims ownership of several lots in the vicinity of the Tyra registration parcel which he identified by reference to the Assessors map as follows: lot 69.5 (large tract directly abutting the Tyra parcel on opposite side of Ben Toms Road), all the lots starting with 125 along Halls Gate Way, and lots 69.1-4. [Note 35] How regularly and frequently he visited these properties, and how regularly and frequently he used the northeast and/or southeast paths when doing so, were not detailed. Their location shows that he would not often have traveled to them using the paths, if ever. [Note 36]

As a child, Mr. Hall testified, he had a friend, John Donnelly, whose father owned property that included the lot now owned by Michael Strada and Susan Graves which abuts the Tyra property on the east. See Ex. 3. Mr. Hall testified that, when he was growing up, the land in this area was vacant woodland with meadows, swamp, ponds and old roads. He says he could bike through this area, did so occasionally, and claims when he did so that he would sometimes see cars passing through. When, where, in what numbers, and in what circumstances he saw these cars was not clearly explained. Mr. Hall also testified that Mr. Donnellys father owned a trucking business, would occasionally store things on now Strada/Graves land, and would access his property from Penneywise Path if he was traveling on the Edgartown -Vineyard Haven Road, or Ben Toms Road if he was traveling on the Edgartown -West Tisbury Road. What personal knowledge Mr. Hall has of this was not made clear. He did not claim to have worked for Mr. Donnelly, or to have ridden in the trucks. The routes taken by these trucks, and the associated dates, times and circumstances of their use, was likewise not clearly explained. There is thus no clear, and certainly no persuasive, evidence that they traveled over the northeast path as opposed to staying on Pennywise Path and Ben Toms Road in the locations surveyed and indicated in the Tyras registration plan (Ex. 3). It is also unlikely that they did so regularly and often. As Mr. Hall admitted, the land was vacant woodland. As the evidence shows, the roads were narrow, dirt, rutted, and not easily traveled by trucks or other vehicles.

Most of Mr. Halls testimony concerned his use and observations of Penneywise Path and Ben Toms Road generally, and rarely focused on the pathways at issue. [Note 37] It is thus unclear when, how often, and in what circumstances he used or observed the use of those pathways. The only two parts of his testimony with any attempt at such a focus were these: he testified that, as a teenager, he sometimes used the northeast path to bring friends to Simmons Pond to go ice skating and, more recently, has used that path from time to time depending upon the direction from which he is traveling. The dates, times, frequency and circumstances of such use were neither detailed nor explained. For this reason and the other reasons discussed above, I find that his use of the paths on the Tyra parcel, if any, was only occasional and sporadic.

Mr. Hall was asked to describe the condition of Ben Toms Road as it abuts the Tyra parcel, and testified that this portion of Ben Toms Road is a perfectly driveable dirt road in the woods about 10-12 feet wide in places. But this was contradicted by the actual survey, which puts it no more than 8 feet wide, and Mr. Halls own admission that, when he drives on Ben Toms Road, he is careful so that he does not bottom out. He testified that he occasionally filled in potholes and cleared brush from Ben Toms Road (when, where, and with what regularity was not explained), and also testified that way back when his friend Walter Bettencourt acquired the property along Penneywise Path from John Donnellys father, they cleared brush and overgrowth along Penneywise Path from approximately lot 57.111 to 58.121 as shown on the Assessors map. But there was no explanation of when, and with what regularity, these acts were done. And whether they included any part of the paths at issue was unclear. In any event, they could not have been anything more than sporadic.

There was no credible evidence of any regular or continuing use of the southeast path, if any use at all. Mr. Hall testified this path wasnt really passable; a person could walk through it, but not drive through it. He described it as, at best, either a footpath or a cow path. He does not claim to have used it with any frequency, to have observed anyone else using it, nor did he identify any particular time, date or circumstance of use.

Additional facts are set forth in the Analysis section below.

Analysis

In filing a petition to register land under G.L. c. 185, § 26, the petitioner bears the general burden of proof, and [is] entitled to registration of only the quantity of land to which he could establish title. [I]t is the purpose of registration proceedings to confirm and register existing titles according to their true boundaries, and not to force land transfers from one party to another. McCarthy v. Lane, 301 Mass. 125 , 129-30 (1938). Stated a different way, the plaintiff in a registration petition must satisfy the Court with respect to (1) the legal basis of his or her claim of title to a particular parcel of land, and (2) the correct location of that land on the ground. See Kostorizos v. Samia, 9 LCR 117 , 119-120 (2001). Here, the Tyras seek to register title to the land shown on the 1996 plan (Ex. 3), unencumbered by any access or use rights in others to the pathway shown in the plans northeast corner, any other pathways on or across their parcel, and the elimination of those pathways from the final, approved registration plan. As previously noted, by stipulation of the parties, the two issues in this action are (1) the location of the common boundary line between the Tyra parcel and the gore lot, [Note 38] and (2) the existence and location of various alleged ways across the Tyra parcel and the defendants rights, if any, to use those ways. [Note 39] Only two such ways were put in issue, the northeast corner path and the southeast corner path.

The Common Boundary Between the Tyra Registration Parcel and the Gore Lot

The Halls raise a number of arguments in an effort to cast doubt on whether the Tyras have title, sufficient for registration, to the land shown on the 1996 plan.

At the outset, the Halls dispute the reliability of Attorney Nortons title examination and Mr. Provosts1996 survey, contending that both of them failed to adhere to the relevant Land Court guidelines for title examinations and surveys that were in effect at the time.

With respect to Attorney Nortons title exam, the Halls contend, [t]he general rule for analyzing a boundary dispute based on something other than adverse possession is that the title has to be run back to the person who at one time owned both of the presently contending parcels, citing R. K. Gad III, Trial of Title and Land Use Cases in the Land Court p. 137-38 n.12 in Litigating Real Estate Disputes (MCLE 2000). See Defendants Request for Findings of Fact & Rulings of Law at 10. I disagree. There simply is no requirement that a title examination must go back until a common grantor is found. Even the Land Court guidelines cited by the Halls state that a title examination shall be for a period of 50 years (or longer if a 50 year search does not provide a good starting point). [Note 40] 28A Mass Prac. Sec. 192 (West 1981). Attorney Norton filed his report to the Land Court in 1991 and began his title exam with the 1879 deed, thus going back 112 years which more than complies with the Land Court guidelines in effect both at the time and presently. And, as previously noted, the Halls have not offered any competent evidence that calls that deed or its validity to convey the property described therein into question. [Note 41]

With respect to the 1996 plan, the Halls contend that Mr. Provost failed to adhere to the Land Courts 1989 Manual of Instructions for the Survey of Lands and Preparation of Plans [Note 42] and, for that reason, his work should be disregarded. Section B(3) of that Manual provides, the surveyor is required to study instruments of record affecting land or lines before the Court

. Section C(6) states that a surveyor should consult other survey standards such as 250 CMR 6.00 entitled Procedural and Technical Standards for the Practice of Land Surveying. The Halls argue Mr. Provost failed to comply with these provisions because he did not examine any deeds to the abutting properties, and instead focused solely on the 1796 deed that created the gore lot. That argument fails for at least two reasons. First, the title examiner (Attorney Norton) reviewed each of those abutters deeds, and the surveyor who did the original 1982 survey (Dean Swift) did so using those properties as monuments. Second, the 1989 Manual plainly states that [i]t [was] not intended as a text for surveyors nor as a standard for all property line surveys. 1989 Manual at 1 (emphasis added). Here, Mr. Provost was not asked to prepare an entirely new survey of the Tyra parcel. Mr. Swift had done a sufficient one before. Mr. Provosts task was limited to establishing a single boundary line that would sever the gore lot from the Tyra parcel, thereby making it suitable for registration. In completing this, Mr. Provost did not simply draw an arbitrary line across the 1982 plan. He consulted with the Land Courts Engineering Department, located and confirmed the boundaries as indicated on Mr. Swifts plan, and then relied on those boundaries in preparing his own supplemental plan. No competent evidence was presented that called into question Mr. Swifts work in preparing the 1982 plan. [Note 43] Mr. Provost had served as an apprentice to Mr. Swift from 1968 until 1983 and had no reason to believe that his plan wasnt [done to] the best of his ability

to place those lines

. I have reviewed all the evidence and concur that those lines were properly placed.

What is truly at issue on the survey side of this dispute is the line set by Mr. Provost for the common boundary between the Tyra registration parcel and the gore lot. The key issues here are (1) whether the white quartz rock, found in the ground by Mr. Provost during his fieldwork and determined by him to be a monument placed there in the past for that purpose, is the proper starting point for the boundary with the gore lot, and (2) whether the line Mr. Provost drew, beginning at the white quartz rock and extending to the side of Ben Toms Road, shows the minimum boundary of the Tyras land. Since the Tyras are not required to register all their land, only the land they choose to register and can prove title to, the registration line need not go all the way to the gore lot. Any land the Tyras own beyond that line to the south would simply be land in which they have recorded title, not registered. [Note 44]

The location of a disputed boundary is a question of fact to be determined on all the evidence. Hurlbert Rogers Machinery Co. v. Boston & Maine Railroad, 235 Mass. 402 , 403 (1920). When deed construction is a part of that analysis, the law provides:

a hierarchy of priorities for interpreting descriptions in a deed. Descriptions that refer to monuments control over those that use courses and distances; descriptions that refer to courses and distances control over those that use area; and descriptions by area seldom are a controlling factor. Moreover, when abutter calls are used to describe property, the land of an adjoining property owner is considered to be a monument.

Paull v. Kelly, 62 Mass. App. Ct. 673 , 680 (2004) (internal citations omitted). But this is not an absolute hierarchy. The law recognizes that descriptions sometimes vary often due to differences in measurements taken at different times by different persons and allows the court, after considering all the evidence, to resolve any differences and set boundary lines where the totality of the evidence indicate they should be set. See Paull, 62 Mass. App. Ct. at 682, n. 16; Browns Boundary Control and Legal Principles (4th Ed.), John Wiley & Sons Inc., New York (1995), §2.6 at 32.

In preparing the 1996 supplemental survey, Mr. Provost did not start from scratch. He had the benefit of Mr. Swifts 1982 survey, the 1796 gore lot deed from John Coffin to William Vinson, the 1980 survey plan in Case File 233 (prepared by the Halls), and Attorney Nortons Report to the Land Court summarizing his title examination. From these documents, Mr. Provost knew the general location of the gore lot was to the south of the Tyra parcel, near the intersection of Ben Toms Road and Middle Line Road.

Knowing the approximate location of the gore lot, Mr. Provost then relied on the description in the 1796 deed to establish its boundaries on the ground. Based on the totality of the evidence presented at trial and for the reasons explained more fully below, I find and rule that Mr. Provost properly concluded that the white quartz rock was the starting monument referred to in the 1796 deed. The white quartz rock is in the location called for in that deed [Note 45] and is distinct from the other stones found in that part of the Island, thus supporting the inference that it was set there to establish a boundary. The quartz rock also fits with the 1796 deed description which begins at a stake and stone. As Mr. Provost testified, the stake referenced in the deed would most likely have been made of wood and thus it would have been unusual to find it some 200 years later. The only thing that could conceivably have survived intact for that period of time is the stone.

Although Mr. Provost did not rely on the description found in the Ericksons chain of title when he prepared his survey plan in 1996, that deed description (given to him around the year 2000 by the defendants) supports his conclusion that the quartz rock is the proper beginning point for the gore lot. The Erickson property, which abuts the Tyras southwestern boundary, begins at a stone set in the ground by the way or path that leads from the Plains to the place which was formerly Simmons Vincents. Testimony showed the path leading to the Simmons Vincent place is Middle Line Road. The quartz rocks location, set in the ground near Middle Line Road, matching the description in the Erickson chain of title, is further confirmation that the quartz rock marks the beginning point of the gore lot and establishes the proper boundary between the gore lot, the Tyra parcel and the Erickson property.

The Halls contention that the quartz rock does not mark the starting point for the gore lot is not supported by the evidence. At trial, the Halls argued that the whole case rises or falls on the location of [the western boundary between the Tyra parcel and the Erickson lot]. This line is critical, they contend, because it could pivot at a different angle thereby shifting the starting point of the gore lot elsewhere along Middle Line Road. The Halls sought to offer as evidence a plan of land, purportedly of the Erickson property, showing its boundary line with the Tyra parcel falling not at the quartz rock, but at a point further up Middle Line Road. This plan, however, could not be authenticated and there was no indication it was ever recorded in the registry. It was therefore not admitted as evidence.

The Halls also offered a different argument with respect to the starting point of the gore lot. Relying on their 1980 survey plan in Case File 233, they contend the proper starting point is not the white quartz rock, but instead could be the large stone shown on that plan falling on the opposite side of Middle Line Road. See Ex. 2. This contention was not supported by the testimony of any surveyor (the Halls had none), and is not supported by the evidence admitted at trial.

This argument by the Halls rests on their contention that Attorney Norton and Mr. Provost incorrectly assumed that one of the boundaries of the gore lot was Middle Line Road, pointing to the fact that the 1796 deed conveying the gore lot states southeast by said Williams land instead of describing this boundary by Middle Line Road. But this assertion that the gore lot deed begins at a point on the opposite side of Middle Line Road and that Middle Line Road might not be a proper boundary of the gore, is undercut by other evidence submitted by the Halls. The only way the gore lot could begin on the other side of Middle Line Road is if John Coffin, the grantor in the 1796 deed, owned land to the south of Middle Line Road. But the Edgartown Proprietors Records, which the Halls contend marks the first division that created the lots now at issue, describes the southeastern boundary of that division as being by Middle Line Road. See Edgartown Proprietors Records, Vol. II, Page 216 (Trial Ex. 10E). There is no evidence that when John Coffin conveyed the gore lot in 1796, the southern boundary of his lot extended beyond Middle Line Road. Thus, the starting point depicted on the Halls 1980 survey, falling on the southern side of Middle Line Road, cannot be the proper bound for the gore lot. As noted above, the Halls presented no surveyor of their own to counter Mr. Provost despite having ample opportunity and time to do so. The subsequent recording by the Halls attorney and son, Benjamin Hall Jr., of the gore lot plan prepared by Mr. Provost for the Gore Realty Trust (Ex. 4, attached), containing the same boundaries and lines as the 1996 plan, is further evidence that even the defendants believe the white quartz rock was the proper starting point of the gore lot.

Having established the white quartz rock as marking the northwest corner of the gore lot, the question now becomes whether Mr. Provosts survey line from the quartz rock to Ben Toms Road shows the minimum common boundary between the Tyra parcel and the gore lot (i.e. the least amount of land owned by the Tyras). Since the Tyra deeds simply reference the abutting property as the southern boundary, the inquiry thus turns to the boundary as described in the gore property deed the 1796 deed from Coffin to Vinson that created it. As previously noted, that deed describes the gore lot boundaries as:

Beginning at a stake and stone set in the ground, by the side of the land belonging to Jonathan Pease, and is the bound between the said John and said Williams land, from said stake and stone about Southeast by said Williams land until it comes to the Northwest side of a cartway to a stone set in the ground, from thence about Northeast by the side of said cartway about thirteen rods to a stone set in the ground, or so far as to make one Acre of Land, and from thence Northwesterly to the first mentioned stake and stone by the side of the said Jonathans land, the said Acre lying in a gore.

In the hierarchy of deed interpretation, distances generally control over area. See Paull v. Kelly, 62 Mass. App. Ct. 673 , 680 (2004). It is seldom that area can be a controlling factor. Temple v. Benson, 213 Mass. 128 , 132 (1912). However, area may be used as an interpretive aid where other interpretive aids are inconclusive. Lukas v. Black, 7 LCR 188 , 191 (1999) (citations omitted). The only distance given in the 1796 deed is 13 rods by the side of a cartway, determined to be Ben Toms Road. 13 rods is the equivalent of 214.5 feet (1 rod equals 16.5 feet). Mr. Provost, however, set his boundary further than 13 rods, going 222.93 feet northeasterly on Ben Toms Road until his calculations yielded an acre of land. [Note 46] Mr. Provost thus gave more weight to the area called for in the deed rather than the precise distance given. [Note 47] This reflects a cautious approach by Mr. Provost that actually gives the gore lot more land than a strict 13 rod measurement. Under the long held rule of deed construction favoring distances over area, it may in fact be that the Tyras own more than what is shown on the 1996 plan if the proper boundary for the gore lot only runs 13 rods (214.5 feet) along Ben Toms Road instead of 222.93 feet. The Tyras, however, do not have to register all their land and are content for now to leave their title, if any, to that extra land and, potentially, the gore lot itself, as recorded only. For purposes of this registration, the Tyras need only prove their title to the boundary shown on the 1996 plan (the land they seek to register). I agree with Mr. Provost that the white quartz rock is the proper starting point for the gore lot and, coupled with the distance and area described in the 1796 deed, am persuaded that the Tyras have proved their title to at least the boundary line depicted on the 1996 plan. I so find. The land shown on that plan is thus proper for registration.

Rights to the Paths Crossing the Tyra Parcel

The remaining aspect of this case concerns the Halls claim to have rights, either by deed, adverse possession or prescriptive easement, to certain pathways crossing the Tyra parcel. The testimony focused on two paths, one crossing the northeastern corner of the Tyra parcel from Ben Toms Road to Penneywise Path (shown on both the 1982 and 1996 plans, Exs. 1 and 3, attached) and the second allegedly crossing the southeastern corner of the Tyra parcel and continuing through the gore lot (this path is not shown on the 1982 or 1996 plans, but is depicted on the 1980 Hall survey from Case File 233, Ex. 2, attached).

The Halls claim of deeded rights to the path crossing the northeastern corner of the Tyra parcel has no merit. It stems from a deed the Halls received from William Prime, dated October 8, 1976 and recorded in Book 292, Page 410, in which Mr. Prime conveyed all my right title and interest, if I have any to the land in Edgartown once owned by Clarence Dutton and Jonathan Norton before him. The deed from Norton to Dutton (Jan. 1, 1912, Book 130, Page 122) purports to convey a right of way over the road leading from the Vineyard Haven Road to the Simmons Vincent place over such land as I own. Ms. Goodale went to the Registry in search of deeds seeking to establish common ownership [of land located south of the Edgartown Vineyard Haven Road] in the name of Jonathan Norton. To do so, she ran the grantee index to determine what land Jonathan Norton might have owned at the time he allegedly conveyed a right of way to Clarence Dutton. Ms. Goodale found deeds naming Nicholas Norton as grantee, [Note 48] but never explained the relationship between Jonathan Norton and Nicholas Norton and at points in her testimony seemed to conflate the two. [Note 49] For instance, at Trial Transcript page 2-224, lines 8-10, Ms. Goodale testified, This is also a document I found conveying property to Jonathan Norton. Its a deed in book 66, page 314, dated August 24th, 1874. That deed, however, names Nicholas Norton as the grantee. See Trial Ex. 32, Deed, Shubael Norton to Nicholas Norton (Aug. 24, 1874) recorded in Book 66, Page 314. Aside from this, as a title abstractor who has never certified title, Ms. Goodale was not qualified as an expert to offer her opinion as to what rights these documents she found allegedly convey. Nor was it ever shown that Nicholas or Jonathan Norton ever owned the Tyra parcel, and thus the deed from Jonathan Norton to Clarence Dutton, allegedly granting a right of way over land owned by Mr. Norton, could not have included any rights to any path crossing the Tyra parcel. See Kitras v. Town of Aquinnah, 64 Mass. App. Ct. 285 , 292 (2005) (Thus [rights in a way] can be created only out of other land of the grantor

never out of the land of a stranger) (internal citations and quotations omitted)

Correspondence between Mr. Hall and Attorney Henry Thayer that the Halls sought to admit into evidence, purporting to contain Attorney Thayers opinion on deeded rights to the paths at issue, were excluded as inadmissible hearsay. [Note 50] The Halls did not submit any deeds reflecting such rights. The only testimony given by an experienced title examiner was that of Attorney Norton who found no mention of any rights to use the paths crossing the Tyra parcel in any of the deeds he examined. I thus find that neither the Halls, nor anyone else, have any express, deeded easement rights to any pathways across the Tyras land.

The Halls remaining theories concern alleged rights acquired by either adverse possession or prescriptive easement. These are similar, but not identical, theories. Title to land may be acquired by adverse possession by proving open, adverse, exclusive, continuous and uninterrupted possession for twenty years or more. See G.L. c. 260, § 21 (prescribing twenty year statute of limitations period for recovery of land); Town of Nantucket v. Mitchell, 271 Mass. 62 , 68 (1930). A prescriptive easement may be acquired by open, adverse, continuous and uninterrupted use of anothers property for twenty years or more that is non-exclusive. See G.L. c. 187, § 2 (codifying elements of prescriptive easement); Tucker v. Poch, 321 Mass. 321 , 323 (1947); Boothroyd v. Bogartz, 68 Mass. App. Ct. 40 , 44 n.9 (2007). The two are identical in this, however; each and every element must be proved for that claim to succeed, and the burden of proving each element is entirely upon the claimant. Rotman v. White, 74 Mass. App. Ct. 586 , 589 (2009). All these elements are essential to be proved, and the failure to establish any one of them is fatal to the validity of the claim. In weighing and applying the evidence in support of such a title, the acts of the wrongdoer are to be construed strictly, and the true owner is not to be barred of his right except upon clear proof of an actual occupancy, clear, definite, positive, and notorious. Cook v. Babcock, 65 Mass. 206 , 209-10 (1853). If any of these elements is left in doubt, the claimant cannot prevail. Mendonca v. Cities Serv. Oil Co., 354 Mass. 323 , 326 (1968) (internal citations omitted).

The adverse possession claim fails, among other reasons, because the Halls failed to show exclusive possession of any pathway on the Tyra parcel. They do not claim to have created these pathways, which I find most likely were put there and used by past owners of the Tyra land as access for them to get to and around the parcel and to obtain and cut wood. And both the adverse possession and prescriptive easement claims fail for lack of proof of open, adverse, continuous and uninterrupted use for twenty years or more. Mr. Hall claims to have driven on at least the northeastern corner pathway, but I find that he did so sporadically at best. [Note 51] This does not suffice to confer the rights he seeks. [Note 52]

The Halls final argument focuses on a 2008 amendment to the Towns zoning bylaw, adding Section 14.2.2 which purports to designate the path crossing the northern corner of the Tyra parcel as a Special Way. Whatever its validity (the bylaw does not indicate what, if any, evidence it was based upon, nor contain any assurance of accuracy), it is only a zoning bylaw and thus can only regulate use. It does not, and cannot, create any property rights in the general public, and does not affect in any way the Tyras title to the land they seek to register. Furthermore, to the extent that the bylaw designates the path crossing the Tyra parcel as being part of Ben Toms Road, see 14.2.2(b)(2), such a designation is at odds with the plans and other evidence admitted into evidence in this case which show Ben Toms Road continuing in more or less a straight line until it intersects with Penneywise Path. The Towns designation thus appears to be inaccurate and I give it no evidentiary weight. See Williams v. Norwell Board of Appeals, 21 LCR 25 , 28-29 (2013) (Cutler, J.); Wrentham v. Bezema, 3 LCR 15 , 17 (1995) (Kilborn, J.) (rejecting tax assessors maps for similar reasons).

Moreover, I do not find that Section 14.2.2 supports an inference of a general right in the public to use the path. It has never been taken as a public way, and a public right of way by prescription depends on a showing of actual public use, general, uninterrupted, continued for the prescriptive period [twenty years]. Fenn v. Middleborough, 7 Mass. App. Ct. 80 , 84 (internal quotations omitted), citing Jennings v. Inhabitants of Tisbury, 5 Gray [71 Mass.] 73, 74 (1855). See also Commonwealth v. Coupe, 128 Mass. 63 , 68-69 (1880). The further fact must be proved, or admitted, that the general public used the way as a public right; and that it did must be proved by facts which distinguish the use relied on from a rightful use by those who have permissive right to travel over the private way. Fenn, 7 Mass. App. Ct. at 84, quoting Bullukian v. Franklin, 248 Mass. 151 , 155 (1924).

Here, the evidence failed to show that the path crossing the Tyra parcel was ever used by the general public as a public right. It should be noted that notice of this case was given to all whom it may concern by publication in the Vineyard Gazette on May 10, 1991. If the Town believed there was a public right by way of prescription to the path at issue, it could have intervened to protect that right. The mere existence of a path crossing the Tyra parcel, in and of itself, does not give rise to an inference that the path was created by the public treading through this area over the years. As noted above, and supported by Mr. Provosts testimony, those paths were most likely created and used by the owners of the Tyra parcel. It is significant that Mr. Hall, who has spent his entire life in Edgartown, called no other witnesses to testify to their personal use, much less general use by the public, of any pathway across the Tyra parcel. In these circumstances, the absence of such evidence is evidence that there was no such public right.

Conclusion

For the foregoing reasons, I find and rule that the petitioners have established registrable title to the land shown on the 1996 plan, subject to the rights of persons entitled or who may become entitled to use the portions of Penneywise Path, Ben Toms Road and Middle Line Road in the locations shown on the 1996 plan. I further find and rule that no one other than the petitioners have any rights in the paths crossing the northeastern corner of the parcel, the southeastern corner of the parcel, or elsewhere, whether express, implied, by adverse possession or prescriptive easement. All such paths shall be eliminated from the plan accompanying the decree of registration.

Registration shall enter accordingly.

SO ORDERED.

My exclusion of any testimony seeking to offer her conclusions or the completeness or accuracy of her work was not pedantic. Her title research was not a straightforward exercise, reflecting the unambiguous conveyance of indisputably the same property from owner to owner. Instead, it involved judgments that the Tyra parcel might be included in an earlier-described parcel, that the owners of that parcel might be the same as those involved in a later conveyance, and that all relevant deeds and interests had been located and accounted for. These are matters of expertise legal and surveying and beyond Ms. Goodales qualifications and competence to make. I thus find that the Halls have not cast Attorney Nortons title examination into doubt, and his commencement of his title search with the 1879 deed, bringing it forward to the Tyras, is sufficient under the relevant title standards for registration by this court.

GORDON TYRA v. BENJAMIN HALL individually, as trustee of BEN TOM REALTY TRUST, and as personal representative under the will of THERESE HALL.

GORDON TYRA v. BENJAMIN HALL individually, as trustee of BEN TOM REALTY TRUST, and as personal representative under the will of THERESE HALL.