HELEN M. DUNHAM vs. FREDERICK A. DODGE & others.

HELEN M. DUNHAM vs. FREDERICK A. DODGE & others.

Way, Private. Easement, Right of way. Equity Pleading and Practice, Bill, Decree.

The owner of farm land bounding northerly on a public way and westerly on another farm, who was entitled to a right of way over a lane thirteen feet wide, running northerly along his westerly boundary to the public way and enclosed on its easterly and westerly sides by fences, and also to another right of way over the adjoining farm running to the public way and parallel to the enclosed lane but not expressly located by deed nor defined as to its width although shown on the surface of the ground by cart ruts, constructed a gate at the southwesterly corner of his land in the fence which was the easterly boundary of the first lane. Opposite that gate, the owner of the adjoining land constructed a barway in the fence which was the westerly boundary of the first lane and thus gave access across the first lane to and from the second lane. Held, that these acts warranted the inference that both of the adjoining owners understood and

Page 368

mutually agreed that the way should be located at the place shown by the gate and the barway.

Where a right of way from a farm across an adjoining farm to and from a public way was given by deed without limitation or reservation and the width of the way was not defined, the easement was to the use of a way of reasonable width; and, in determining what is a reasonable width, the character and configuration of the land, the purposes for which the land and the way were used at the time of the grant, and all the circumstances attending the grant are to be considered.

Where the farms of two adjoining owners were bounded northerly on a public way and the owner of the easterly farm was entitled to a right of way, created by deed in 1887 without limitation or restriction, over the westerly farm and defined by conduct of the owners on the surface of the land as running over land which sloped sharply toward the east, southerly from the public way and parallel to the westerly boundary of the first farm to a point opposite its southwesterly corner, then turning nearly at a right angle and running easterly across a lane to that farm, a barway ten and eighteen one hundredths feet in width, erected by the owner of the westerly farm to give access to and from the way, properly may be found, in a suit to enjoin its maintenance as an obstruction to the right of way, not to be of sufficient width.

Although, in a suit in equity to enjoin the maintenance by the defendant of a barway only ten and eighteen one hundredths feet wide in a fence at the point where the plaintiff had access to a right of way to which he was entitled over land of the defendant, the prayers of the bill do not specifically include a request that a proper minimum width for the barway be determined, if, upon evidence warranting it, a finding is made by the trial judge that the width of the way should not be less than fifteen feet, it is proper to include in the final decree an order that the opening in the defendant's fence should not be less than that width.

BILL IN EQUITY , filed in the Superior Court on May 27, 1919, against Frederick A. Dodge, Isabelle J. Dodge, Mildred K. Lunt, and Alfred E. Lunt, seeking to enjoin the defendants from obstructing the right of way described in the opinion.

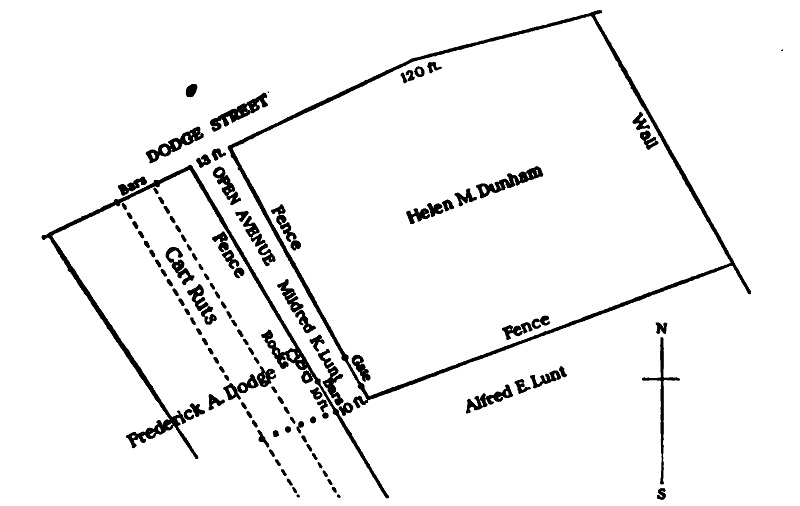

The suit was heard in the Superior Court by Fox, J., a commissioner having been appointed under Equity Rule 35 to take the testimony. The material evidence is described in the opinion. The plan there referred to, with some variation of details illustrating facts material to the decision of this suit, is shown on page 369.

The judge filed a memorandum, stating, "The plaintiff's right of way over Dodge's land has been improperly obstructed, and she is entitled to a decree against them. The bill as to the defendants Lunt is to be dismissed."

By order of the judge, a final decree was entered, "that the rocks and the fence referred to in the plaintiff's bill unreasonably obstruct the plaintiff's right of way over Dodge's land, and the

Page 369

defendants Dodge are required to remove them forthwith, except that the defendants may maintain a fence on the dividing line between the land of Lunt and the land of Dodge, with an opening not less than fifteen feet in width at a place opposite the plaintiff's gate, and close said opening with a gate or an easily removable set of bars, whenever said opening needs to be closed for the proper

uses of their land. The rocks are to be removed from their present position so that they will not obstruct a way fifteen feet in width, curving with an easy turn from the opening aforesaid northerly into the cow lane or farm road now upon said Dodge's land, running to Dodge Street."

The defendant Frederick A. Dodge appealed.

S. Perley, (A. E. Lunt with him,) for the defendant Frederick A. Dodge.

E. E. Gordon, for the plaintiff.

CROSBY, J. By deed dated August 13, 1887, Andrew Dodge (father of the defendant Frederick A. Dodge) conveyed to Charles K. Ober a portion of his farm comprising the tracts now belonging to the plaintiff and the defendants Lunt, with a frontage of one hundred and thirty-three feet on Dodge Street in Beverly "together with a right of way to pass and repass, to and from said granted premises, over my own land, on the westerly side thereof." The parties to this conveyance erected a fence along the boundary

Page 370

line between their respective tracts. In the year 1888 Ober conveyed to one Carr a lot eighty-nine feet deep and having a frontage of one hundred and twenty feet on Dodge Street "together with an open right of way over my strip of land adjoining lot conveyed in this deed to the west, and including also a right of way over land of Andrew Dodge on the west of the before mentioned strip of land belonging to me." The land so conveyed by Ober to Carr is now owned by the plaintiff. The defendant Dodge is the owner of the remainder of the farm not conveyed as above described by Andrew Dodge to Ober.

The land of the plaintiff has been duly registered by decree of the Land Court, dated May 16, 1919, which recites that "There is appurtenant to the above described land an open right of way to pass and repass for all purposes between the above described land and Dodge Street over a strip of land marked 'Mildred K. Lunt' shown as a right of way on said plan, in common with others entitled thereto; and also a right of way over land now or formerly of Frederick A. Dodge et al., as shown on said plan, as described in a deed given by Andrew Dodge to Charles K. Ober, dated August 13, 1887, duly recorded, . . . in common with others entitled thereto." It thus appears that there is appurtenant to the land of the plaintiff an open right of way thirteen feet wide, over land of Mildred K. Lunt adjoining the plaintiff's land on the westerly side thereof, which runs from Dodge Street in a southerly direction past the plaintiff's land; and also a right of way over land of the defendant Dodge adjoining and westerly of the way over the land of Mildred K. Lunt. Running through the Dodge farm to the south from Dodge Street is an elevation sometimes called Indian Ridge over which runs the Dodge lane. This lane was used by the owners of the Dodge farm as a cow lane, and cart ruts are visible on the surface of the ground. There is a stone wall on the westerly side and a fence along the easterly boundary; the land slopes abruptly away from the ridge, along the top of which is the travelled part of the lane. When Dodge Street was relocated about the year 1875 it was about six feet below the level of the lane and the latter was levelled off making it accessible from the street.

The bill as to the defendants Lunt having been ordered dismissed, the case is before us on appeal from the final decree of the defendant

Page 371

Frederick A. Dodge. No question is raised as to the right of the plaintiff to pass over the cow lane, so called, on the Dodge land to a point nearly opposite the southwest corner of her own land, and across the thirteen-foot strip to her own land, the only issue being as to the width of the opening in the boundary fence between land of Dodge and Lunt. The defendant Dodge has erected a barway in the fence with two posts set ten and eighteen one hundredths feet apart, which he contends is a reasonable width, to be used by the plaintiff in the exercise of the easement. He has deposited three large rocks along the boundary line close to the northerly barpost and also has set a row of posts in the ground across the cow lane at a point about opposite the southerly barpost. These obstructions prevent large automobile trucks from using an opening greater than ten and eighteen one hundredths feet wide in passing to and from the plaintiff's land.

The plaintiff contended and offered evidence tending to show that the narrowness of the barway makes it impossible for large coal trucks to pass to and from her premises over the right of way, and that an opening at least fifteen feet in width is necessary for a reasonable use of the way. The width of the right of way over the Dodge land is not described in the deed creating it, nor is it defined in the decree of the Land Court. It is settled, however, that where a right of way is granted without fixing its location but there is a way already located at the time of the grant, such way is held to be the location of the way granted. O'Brien v. Schayer, 124 Mass. 211. Gerrish v. Shattuck, 128 Mass. 571. If the grant creating a right of way does not define its location, the owners of the dominant and servient estates may expressly agree upon such location or by conduct may be found to have impliedly agreed to the location. The plaintiff built a gate in her fence near the southwest corner of her lot, and the defendant placed the barway in the boundary fence between his land and the thirteen-foot strip at a place substantially opposite her gateway. These acts warrant the inference that both parties understood and mutually agreed that the way should be located on the surface of the ground at that place. Bannon v. Angier, 2 Allen 128. George v. Cox, 114 Mass. 382.

The plaintiff in the exercise of her right to use the way was limited to such use as was reasonably necessary. In determining what is a reasonable width of the barway for the use of the plaintiff

Page 372

reference must be had to what was presumed to have been in the minds of the parties at the time of the grant. The plaintiff is not entitled to a way of greater width than was reasonable at the time of the grant because of changed conditions. Johnson v. Kinnicutt, 2 Cush. 153. Atkins v. Bordman, 2 Met. 457, 467, 468. A grant of a way over one's own land without limitation or restriction is understood to be a general way for all purposes, but is limited to the nature and condition of the subject matter at the time of the grant and the obvious purposes which the parties had in mind in making it. Rowell v. Doggett, 143 Mass. 483. As the width of the way is not specified and as it is not limited to any particular purposes, the question is, what is a reasonable width for the owner of the dominant estate to use in passing to and from the cow lane to her land. In determining this question, the situation of the parties, the character and configuration of the land, the purposes for which it was then used, and all the circumstances are to be considered.

It is plain that at the time of the grant in 1887 and previously the entire tract had been devoted to farming purposes, which would include the tilling of the soil and the raising of crops, and it well might be inferred that it was intended by the parties that a reasonable use of the way contemplated the passage of teams with heavy loads, such as hay and other farm produce, which would require a space wider than would be necessary for lighter and smaller vehicles. There was evidence that the cow lane over the Dodge land extended from the street in a southerly direction over land which sloped off sharply toward the west, and that at a point opposite the barway erected by the defendant the width of the way that could be used for the purposes of travel was limited to twelve feet and teams passing through the barway in either direction would be obliged to turn nearly at right angles. Manifestly the way must be of such width as to be of practical use to the plaintiff. What would be sufficient for a heavily loaded team travelling along a straight line might not be in case of a way with sharp angles and curves, as more room would be required in turning angles than in passing in a straight line. Walker v. Pierce, 38 Vt. 94.

We are of opinion that under existing conditions it cannot be said that the trial judge erred in finding that the plaintiff's right

Page 373

of way was improperly obstructed by reason of the fence and rocks. Whether a suitable and convenient use of the way in view of the narrowness of the cow lane opposite the barway required an opening in the fence not less than fifteen feet in width, was a question of fact, and the finding of the trial judge cannot be said to be plainly wrong. O'Linda v. Lothrop, 21 Pick. 292. Atkins v. Bordman, supra. Underwood v. Carney, 1 Cush. 285. Johnson v. Kinnicutt, supra. Crosier v. Shack, 213 Mass. 253.

The defendant as the owner of the servient estate was entitled to fence the sides of the way if necessary for his own protection, and could erect and maintain at his own expense a suitable barway in the fence. He was not required to erect a gate at that point but could maintain either a barway or gate, and the decree so provides. Ball v. Allen, 216 Mass. 469. No valid objection to the maintenance of the bill can be sustained because it prays for injunctive relief and does not seek to establish the width of the way. The plaintiff was entitled to a suitable and convenient means of passing between her premises and Dodge Street, and the decree respecting the width of the barway is merely incidental to the relief prayed for. Johnson v. Kinnicutt, supra. Tudor Ice Co. v. Cunningham, 8 Allen 139. George v. Cox, supra. Stetson v. Curtis, 119 Mass. 266. Lipsky v. Heller, 199 Mass. 310, 318.

Decree affirmed.