CHARLES CETLIN vs. PEARL S. BRADFORD.

CHARLES CETLIN vs. PEARL S. BRADFORD.

[Note: This opinion was revised by the court in v. 289 of Massachusetts Reports. The text below is that of the revised opinion.]

A tenant in common of a freehold has a title which makes effective a release to him of an encumbrance or easement relating to the property so owned.

A tenant in common is entitled to equitable relief against a stranger to the title to prevent a trespass.

In a suit in equity to enjoin the defendant from exercising an alleged right of way in land owned by the plaintiff, there was evidence that in 1812 two tenants in common of four parcels of land, A, B, C and D, and a passageway between them, lots A and D being on one side of the passageway and lots B and C on the other, by partition deeds, conveying lots A and B to one and lots C and D to the other, reserved the passageway, describing it by metes and bounds as a separate parcel, for the accommodation of the lots of both, one deed providing for its use in the manner in which it theretofore had been used and that it was

Page 435

to be "in common and undivided;" that in 1875 lots A, B and C came into the possession of the predecessor in title of the plaintiff and of the defendant by deeds bounding the lots on the passageway and sufficient in description to carry the grantor's interest in fee in the passageway; that in 1913 lot A was conveyed to the plaintiff and his brother by the trustees under the will of the owner in 1975 with all the rights of themselves and of their testator in the passageway and in the land of the passageway; that in 1920 after the commencement of this suit a strip of land two feet in width, a part of lots B and C extending from a public way and bounded upon the "passageway laid down by" the tenants in common in 1812 was conveyed by the trustees to the defendant. Held, that

(1) The partition deeds of 1812 were to be construed together and the intent of the parties as expressed by all their terms governed;

(2) The tenants in common in 1812 owned the fee of the land in the way as tenants in common;

(3) The entire title in common which such mutual predecessor in title had in the fee of the way and to its use had passed to the plaintiff when the conveyance of the narrow strip bounding on the way was made to the defendant in 1920 and the defendant therefore could receive no right of way as appurtenant to that strip;

(4) As the narrow lot conveyed to the defendant bounded for its full width on another way which the grantee had a right to use, no way existed by necessity;

(5) The plaintiff was entitled to a decree enjoining the defendant from using as a way the land in controversy and from interfering with the plaintiff's enjoyment and occupation thereof.

A decree in a suit in equity where costs are imposed should state therein the amount of costs to be paid.

BILL IN EQUITY, filed in the Superior Court on January 14, 1920, alleging a continuing trespass upon land in Newburyport owned by the plaintiff and praying for an injunction and for damages.

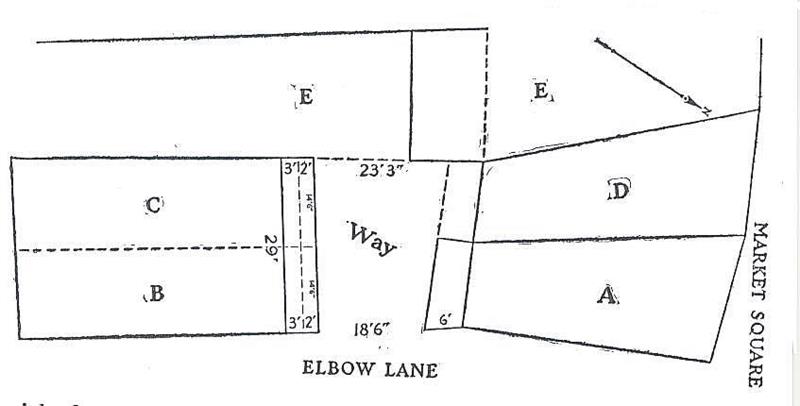

In the Superior Court, the suit was referred to a master, who filed a report accompanied by a plan. A copy of the plan, somewhat reduced, is shown on page 436. The findings of the master, other than those described in the opinion, were in substance as follows: " that for more than thirty-five years and probably for a very much longer period, there had been maintained on Elbow Lane a fence between the building of the plaintiff and of the defendant in which there was only a small gate, four or five feet wide; that the premises known as the 'way' were 'used as a yard for storage of fuel and for the hanging of clothes; ' " that " there was an old double toilet therein and that beyond the double toilet, extending from 'D' to 'C' at the dotted line on plan was a high fence, designated by one witness as fourteen or fifteen feet high. That the fence above referred to, had been there for many years, at least

Page 436

for thirty-five years;" that "no vehicles during that period entered upon the way and that the only passage was through the little gate of four or five feet wide for travellers on foot.

"That the maintenance of said double toilet by the owner of the dominant estate, that is the Gersht building and land, together

with the use of said land as a yard, are acts inconsistent with the continued existence of the way as it existed during the early part of the last century and manifest an intention to abandon and extinguish the easement," and therefore "that said way as a way 'for a team or teams' has as a matter of fact been abandoned;" that " the union of the dominant and servient estate to said 'A' and 'B' in 1875, in one owner operated as an extinguishment of said way so far as the land between plaintiff's and defendant's building is concerned;" that "the only way to which plaintiff's premises are now subject is a passage four or five feet wide for foot passage for the occupants of the Gersht property.

"That the plaintiff is entitled to maintain a fence along his boundary abutting on Elbow Lane with a suitable gate therein for foot passage;" that "the plaintiff is entitled to a perpetual injunction restraining the defendant from interfering with the plaintiff's premises or with the fences erected by the plaintiff;" that "the plaintiff has sustained damages by defendant's acts in the sum of $35."

The defendant filed exceptions to the master's report which were founded upon the following objections:

"1. To the admission of plaintiff's testimony as to condition of land in the rear of his premises.

Page 437

"2. To the finding 'that the maintenance of a double toilet by the owner of the Gersht building and land, together with the use of said land as a yard, are acts inconsistent with the continued existence of the way as it existed during the early part of the last century, and manifest an intention to abandon and extinguish the easement.'

"3. To the finding that the 'said way as a way "for a team or teams " has as a matter of fact been abandoned.'

"4. To the finding that 'the union of the dominant and servient estate to said "A and B " in 1875 in one owner operated as an extinguishment of said way so far as the land between plaintiff's and defendant's buildings is concerned.'

"5. To the finding 'that the only way to which plaintiff's premises are now subject is a way four or five feet wide for foot passage for the occupants of the Gersht property.'

"6. To the finding 'that the plaintiff is entitled to maintain a fence along his boundary abutting on Elbow Lane with a suitable gate therein for foot passage.'

"7. To the finding 'that the plaintiff is entitled to a perpetual injunction restraining the defendant from interfering with the plaintiff's premises or with the fence erected by the plaintiff.'

"8. To the failure of the master to give any effect to the defendant's deed, obtained since the beginning of the plaintiff's action, of the strip of land between the plaintiff's premises and the other premises of the defendant."

The suit later was heard by Fisdick, J., who filed the following memorandum:

"This case came before me for hearing on plaintiff's motion to confirm the master's report. The plaintiff did not move to overrule the defendant's exceptions to the master's report, nor did the defendant move with reference to his exceptions. The plaintiff made no motion for any decree but handed to me a proposed interlocutory decree confirming the master's report. Neither party moved for a final decree. However, the case was argued before me by both parties as if it were ripe for action on the exceptions and master's report and for a final decree and as if all necessary motions had been made, and I so treat it.

"The master reports that while the cause was pending in court a deed was delivered to the defendant . . . which was the only

Page 438

conveyance by virtue of which he could have any rights in or over the land which the plaintiff claims to own. The master assesses damages for the plaintiff against the defendant and at the argument before me the defendant's counsel conceded that the defendant did certain acts before the delivery to him of said deed, which acts resulted in damage to the plaintiff and were a trespass and that defendant should pay the plaintiff fair compensation for said damage. The defendant also disclaimed before me that he has or ever had any rights in the alleged passageway by virtue of his ownership of the land described in the master's report as 'Defendant's other Real Estate' and shown as 'Lot E' on the plan annexed to the report. It is clear that until the delivery to the defendant of the deed . . . hereinbefore mentioned the defendant had no basis for any claim of right in the alleged passageway and that the findings of the master excepted to by the defendant would have been unnecessary but for the introduction of that deed. The parties, however, have argued the case before me as though the defendant had been since before the filing of the bill the owner of the land and easements purporting to be conveyed to him . . . [by the deed above described] and as though that deed had in fact been delivered to him at the time of the acts and threats complained of in the bill, save only that the parties have treated the matter of damages as stated above. Although but for the fact of the delivery of the deed . . . the plaintiff might clearly have been entitled to injunctive relief against the defendant, nevertheless, in the interest of doing away with further litigation over the circumstances as altered by the factum of the delivery of the deed I treat the case as the parties have treated it. No point was raised concerning the jurisdiction of equity in the case.

"I am of opinion that the other findings of the master and that the evidence reported by him do not warrant him in making the findings to which the defendant excepts. In so far as his so called findings are rulings of law based on his findings of fact they were not within his province. . . .

"I rule that upon the law and the facts as reported by the master there is appurtenant to the defendant's premises a right of way as laid down in the deeds of Abner Wood to Joshua Greenleaf dated January 24, 1812, . . . and of Joshua Greenleaf to Abner Wood of the same date . . . and that the defendant is an owner in

Page 439

common of an easement of way as created by said deeds, and that the deed of the trustees of the estate of Thomas Mackinney to the plaintiff and his brother conveyed to the plaintiff and his brother only such easements of way as were appurtenant to the land thereby conveyed to the plaintiff and his brother and the fee to the centre of the land affected by and subject to such easements, these rulings being based on the master's report as modified and confirmed.

"I am of opinion that the master's report as confirmed shows nothing more than a long continued non-user of an easement of way created by deed and that no intention to abandon the easement is disclosed, and I so rule. I further rule that the master's report as confirmed does not show as against the defendant any extinguishment of the easement by merger of dominant and servient estates. I rule that the plaintiff is not entitled to the injunctive relief sought, but that the bill may be retained for the assessment and award of damages to the plaintiff in the sum of thirty-five dollars. The plaintiff is to have his costs, taxed as in an action at law, and for his damages and costs may have execution."

By order of the judge an interlocutory decree was entered overruling the defendant's first and eighth exceptions, sustaining his second, third, fourth, fifth, sixth and seventh exceptions and, except as modified by sustaining the exceptions as above stated, confirming the report of the master. Later by order of the judge a final decree was entered as follows:

"That the defendant by virtue of the deed to him from William Balch et al., trustees under the will of Thomas Mackinney, dated October 5, 1920, recorded with Essex So. Dist. Deeds, book 2464, page 263, and acquired after the filing of the plaintiff's bill, now owns as appurtenant to the premises described in said deed an easement of way in a passageway laid down in the deeds of Abner Wood to Joshua Greenleaf dated January 24, 1812, recorded with said Deeds, in book 196, page 222, and of Joshua Greenleaf to Abner Wood of the same date, recorded in book 196, page 221, in common with the plaintiff and such other persons as may have easements therein. That the plaintiff is not entitled to the injunctive relief prayed for. That the bill be retained for the assessment and award of damages to the plaintiff in the sum of thirty-five dollars. That execution issue to the plaintiff for said sum with costs taxed as in an action at law."

Page 440

The defendant appealed from both the interlocutory and the final decree.

The material parts of the deeds referred to in the opinion are as follows:

From deed of Abner Wood to Joshua Greenleaf: "all rights, titles, etc. to certain lot of land with the buildings thereon, situated in said Newburyport, bounded as follows: to wit, beginning at the Northerly corner of the same premises on Market Square and an alley or passageway twelve feet wide, between the premises herein described and land of Richard Pike, thence running southerly by said passageway forty-one feet and ten inches to the back side of the store standing on the same, thence continuing southerly six feet from the back side of said Store to a way reserved by said Greenleaf and Wood for their mutual convenience and accommodation, and for the use of the premises herein described and the lot of land adjoining the premises by deed of even date herewith quitclaimed by said Greenleaf to said Wood, thence running Westerly on a line parallel to the back side of said Store six feet distant therefrom about fourteen feet, thence running northerly through the centre of the partition wall of the Store on the premises herein described and on the premises this day quitclaimed by said Greenleaf to said Wood to Market Square, thence running by Market Square easterly about twenty-two feet to the bounds begun at.

"Also one other lot of land in said Newburyport with the buildings thereon lying back of the premises before described and is bounded as follows: to wit, Beginning at the northerly corner thereof on a passageway twelve feet wide leading from Market Square and the passageway herein before reserved and hereinafter more particularly described and running southerly by said twelve feet passageway thirty-six feet to the back side of the Store standing on the premises hereby described, thence running Westerly by the back side of said Store last mentioned, fourteen feet and six inches Westerly, thence running northerly through the centre of the partition wall of the Store standing on the premises and land this day quitclaimed to said Wood by said Greenleaf to the Passageway herein to be described, thence running Easterly by the same passageway to the twelve feet passageway before mentioned to the bounds begun at.

Page 441

"The way reserved for the accommodation of the Estate herein described, and the Estate this day conveyed and quitclaimed to said Wood, is described and bounded as follows: to wit, the northerly side thereof to be six feet from the back side of the Store first mentioned and to be eighteen feet and six inches at right angles on the easterly side next said twelve feet passageway, and twenty-three feet and three inches wide at right angles on the westerly side next the lot of land owned by Abraham Perkins and others "the described premises with the uses and privileges in common and equal with, we [me], the said Wood of the said passageway herein last described and in the same manner as the same has heretofore been used by and between us and to be in common and undivided forever to him the said Greenleaf, his heirs, et al."

From the deed of Joshua Greenleaf to Abner Wood: "all my rights, titles, et cetera to certain lot of land with the buildings thereon situated in said Newburyport and bounded as follows: to wit, beginning at the northwesterly corner thereof on Market Square by land owned by Abraham Perkins and others, thence running easterly by said Market Square twenty-one feet and six inches to land this day quitclaimed by said Wood to me, thence running southerly through the centre of the partition wall of the Store standing on the premises herein described and land this day quitclaimed to me by said Wood, and to continue on the same line six feet from the back side of said Store to a passageway reserved by said Greenleaf and Wood for their mutual convenience and for the use of their respective estates and is hereinafter more particularly described thence running westerly by said Passageway about thirteen feet and six inches to land owned by Abraham Perkins and others, thence running northerly by land of said Perkins and others, fifty-two feet and six inches to the bound begun at.

"Also one other piece of land in said Newburyport with the buildings thereon bounded as follows: to wit, beginning at the northwesterly corner thereof by the passageway aforesaid, and land owned by said Perkins and others, thence running easterly by said Passageway about fourteen feet to land this day quitclaimed to me by said Wood, thence running southerly through the centre of the partition wall of the Store standing thereon and on land this day quitclaimed by said Wood to me, to the back side

Page 442

thereof, being about thirty-six feet, thence running westerly by the back side of said Store, about fourteen feet, thence by land of said Perkins and others, about thirty-six feet, to the bounds begun at. The way reserved for the accommodation of the Estate herein described and the Estate this day quitclaimed by said Wood to me is bounded and described as follows: to wit, the northerly side thereof to be six feet from the back side of the store first mentioned and to be eighteen feet and six inches wide at right angles on the easterly side next adjoining a twelve feet passageway leading from said Market Square which is also in common between the parties, and subject to the use of Richard Pike and the assigns of him, of the Estate now owned by him on Water Street, and to be twenty-three feet and three inches wide at the westerly end adjoining land of said Perkins and others, as it is situated between the two lots of land herein quitclaimed, and the two lots this day quitclaimed to me by said Wood and to be used equally and in common by the Parties hereto or their assigns forever."

The two parcels conveyed by Wood to Greenleaf are those shown on the plan and referred to in the opinion as lots A and B respectively, and the two parcels conveyed by Greenleaf to Wood are those so shown and referred to as lots C and D respectively.

The case was submitted on briefs.

T. S. Herlihy, for the plaintiff.

E. Foss & C. T. Smith, for the defendant.

JENNEY, J. The plaintiff, alleging that the defendant has trespassed upon his land in Newburyport and that he threatens to tear down a building thereon, seeks injunctive relief and damages. The defendant justifies under a claim of a private way. The plaintiff concedes that such easement formerly existed, but says that it has been terminated. Its present existence is the issue.

In 1812, Abner Wood and Joshua Greenleaf, who were tenants in common of land with buildings thereon situated on the corner of Market Square and Elbow Lane and then used by ship chandlers, executed deeds to each other whereby partition was made. The parcel comprised lots designated as A, B, C, and D, and a passageway between these lots, on a plan annexed to the report of the master who heard the case. Lots A and B became the

Page 443

property of Greenleaf and C and D that of Wood. The way was created by these deeds and in one was described as "reserved by said Greenleaf and Wood for their mutual convenience and accommodation and for the use of the premises." In other places the description was substantially the same. The southerly boundary of A was on a line six feet distant from the back of the store then on the lot, while lot B was described as running easterly on the passageway. The part of the deed of Wood to Greenleaf given in the record thus concludes: "The described premises with the uses and privileges in common and equal with, we [me], the said Wood of the said passageway herein last described and in the same manner as the same has heretofore been used by and between us and to be in common and undivided forever to him the said Greenleaf, his heirs." The northerly boundary of C and the southerly boundary of D are on the way which in the deed of those lots is described as "reserved for the accommodation of the Estate herein described and the Estate this day quitclaimed by said Wood to me" which is "to be used equally and in common by the Parties hereto or their assigns forever." The material parts of these deeds are to be printed herewith. The instruments are to be construed together. Sibley v. Holden, 10 Pick. 249, 250. Perry v. Holden, 22 Pick. 269. Cloyes v. Sweetser, 4 Cush. 403. Porter v. Sullivan, 7 Gray 441, 446. The intent of the parties as expressed by all their terms governs. Davis v. Rainsford, 17 Mass. 207. Temple v. Benson, 213 Mass. 128, 132. As to Sibley v. Holden, supra, see Pinkerton v. Randolph, 200 Mass. 24, 27, but its authority is not impaired upon the proposition to which it is cited.

The way is described by metes and bounds as a separate parcel and is reserved for the accommodation of the lots of both Wood and Greenleaf, and the deed of Wood to Greenleaf provided for its use in the manner in which it heretofore had been used and that it was to be " in common and undivided." If the deeds are construed as conveying the fee in the way, this language must be regarded as meaningless. In a deed so carefully drawn, that is not to be presumed. The provision that the way is to be undivided cannot reasonably be construed as relating only to the easement. Morgan v. Moore, 3 Gray 319. Stearns v. Mullen, 4 Gray 151. Codman v. Evans, 1 Allen 443. See Sibley v. Holden, supra; Clark v. Parker, 106 Mass. 554, 557. It follows that as a result of the partition

Page 444

Greenleaf owned A and B, Wood C and D and that they owned the fee of the land in the way as tenants in common.

The report does not include the deeds given between 1812 and 1875, although they were in evidence. In the latter year, Thomas Mackinney became the owner of lots A, B, and C by two deeds, each purporting to convey land bounding upon the passageway and being sufficient in form to carry the grantor's interest in the fee therein so far as it was appurtenant. The defendant admits in his brief that Thomas Mackinney had under these deeds a title to some part of the fee of the passageway. This concession is confirmed by the master's finding that the dominant and servient estates were in 1975 as to the part of the passageway between lots A and B united in one ownership. In the absence of the evidence it is assumed from the finding and the admission that Thomas Mackinney in 1875 owned the fee in the passageway in common with one or more persons, subject, however, to the rights of way then in existence.

Mackinney then owned three of the lots shown on the plan and at the least had a title as tenant in common in the fee of the way. While he had no distinct easement as owner as against himself as tenant in common, if there were any other persons who owned the fee in the way as tenant in common with him their title was subject to the way appurtenant to his lots, and as against him and them the land was subject to a like right in favor of lot D. This conclusion requires no complete merger entirely extinguishing the easement. Ritger v. Parker, 8 Cush. 145. Crocker v. Cotting, 170 Mass. 68. Tuttle v. Kilroa, 177 Mass. 146. See Gale on Easements (9th ed.) 454; Reed v. West, 16 Gray 283.

The trustees under Mackinney's will on April 2, 1908, conveyed parts of lots B and C to Timothy Harrington. The northerly line fixed by the deed was parallel with and three feet distant from the northerly end of the building on the lot. The line so determined was distant two feet southerly from the southern line of the way. No reference is made to the way in this deed and as the premises did not abut on it the grantee got no interest in the fee or right thereover.

Five years after (March 27, 1913) the same trustees deeded lot A to Charles and Rubin Cetlin with "the rights and privileges in the said passageways which said Thomas Mackinney had and said

Page 445

Trustees have by virtue of his and their ownership of said land, and all the right, title and interest of the grantors to the land in said passageways." As this deed in terms conveyed the rights and privileges which Mackinney or the grantors had in the passageway, and the right, title and interest of the trustees in the land over which it had existed, the title as tenant in common which the trustees had in the fee of the way passed to the grantees and any right of way which they had as appurtenant to any other land was extinguished, except such right as arose from necessity. Needham v. Judson, 101 Mass. 155. Holt v. Somerville, 121 Mass. 574. See Bullard v. New York, New Haven & Hartford Railroad, 178 Mass. 570. After the giving of the deed, the trustees had no land abutting on the way, except a strip two feet in width on Elbow Lane and of the depth of twenty-nine feet westerly from that lane.

Rubin has since conveyed his title to Charles. It is not necessary to consider whether his deed included the interest, if any, in the passageway under the deed from the trustees. His ownership cannot affect the true construction of the deed of the trustees hereinafter considered.

Clearly the trustees had a right to convey the interest in the fee which was owned by them, and also by the same instrument could release to the grantees any right of way vested in them. A tenant in common of a freehold has a title effectuating a release to him of an encumbrance or easement. No question is involved as to the effect of such deed between cotenants. Hurley v. Hurley, 148 Mass. 444. Barnes v. Boardman, 152 Mass. 391, 393. Hill v. Coburn, 105 Maine 437. See Benjamin v. American Telephone & Telegraph Co. 196 Mass. 454, 457. A tenant in common is entitled to equitable relief against a stranger to the title to prevent a wrong of the kind here claimed to exist. Preston v. West's Beach Corp. 195 Mass. 482.

The defendant does not contend that the deed of the trustees to Harrington gave him any title to the fee of the land within the ancient way. He wholly bases his claim of easement on a deed of the trustees dated October 5, 1920, conveying to him the strip two feet wide between the land formerly of Harrington and now of the defendant and the passageway, and bounded easterly on Elbow Lane. The northerly boundary is described as upon "a pas-

Page 446

sageway laid down by Abner Wood and Joshua Greenleaf, January, 1812." But this deed transferred no interest in the fee or easement in the land over which the way had originally existed. Their deed to the Cetlins had foreclosed any right to convey either. No way existed by necessity. The narrow lot bounds for its full width on another way which the grantee has a right to use.

The question of abandonment of the easement need not be considered. It is not contended that the way is or ever was appurtenant to lot E, now owned by the defendant.

The final decree refusing injunctive relief to the plaintiff on the ground that the defendant during the pendency of the suit had become the owner of an easement appurtenant only to the narrow strip owned by him was wrong. It must be modified by striking out the second and third paragraphs and inserting in the place thereof a provision enjoining the defendant from using as a way the land in controversy and from interfering with the plaintiff's enjoyment and occupation thereof.

The final paragraph relating to costs should be modified by stating therein the amount which is to be paid. Rubenstein v. Lottow, 220 Mass. 156.

As so modified, the decree is affirmed with costs.

So ordered.