KAFKER, J. In this case, along with another opinion issued today, Columbia Plaza Assocs. v. Northeastern Univ., 493 Mass. 570 (2023), we revisit the analytic framework of a statute that has played an increasingly prominent, and complex, role in civil litigation over the last thirty years. General Laws c. 231, § 59H, more commonly known as the "anti-SLAPP" statute, establishes a procedure for obtaining the early dismissal of a claim that seeks to impose liability on individuals for exercising their constitutional right of petition. This procedure, referred to as a "special motion to dismiss," has become a frequent subject of our jurisprudence since § 59H was first enacted. This is largely attributable to the open-ended language of the statute, which reaches any claim "based on" a broadly defined category of petitioning activity, and the advantages afforded to a party who successfully invokes it -- including the dismissal of adverse claims and an award of attorney's fees. Indeed, the mere act of filing such a motion serves to automatically stay discovery and prioritize the resolution of the motion over other matters in the case.

Although these powerful procedural protections were designed to target meritless suits brought to discourage individuals from exercising their constitutional right of petition, the statute has been regularly invoked in attempts to dismiss a wide array of other claims concerning conduct far afield of the petitioning

Page 541

activity that the Legislature originally sought to protect. To align the statutory language and purpose, and address its potential misapplication, in Duracraft Corp. v. Holmes Prods. Corp., 427 Mass. 156, 167-168 (1998) (Duracraft), we adopted a construction of the anti-SLAPP statute that would exclude its applicability to claims with a substantial basis other than or in addition to an individual's exercise of the right of petition.

The Duracraft framework governed our jurisprudence for nearly twenty years. However, out of concern that the "problematic sweep of the statute" had continued to invite its misapplication to meritorious claims, this court in Blanchard v. Steward Carney Hosp., Inc., 477 Mass. 141, 155, 159 (2017) (Blanchard I), and Blanchard v. Steward Carney Hosp., Inc., 483 Mass. 200, 206-207 (2019) (Blanchard II), substantially augmented the Duracraft framework, requiring that the factual allegations supporting challenged claims be parsed, so as to allow portions of such claims to be dismissed, and inserting an additional multifactor test to evaluate the subjective motivation of those bringing the challenged claims.

The resulting complexity of this augmented framework, which also strays from the statutory language, has led to additional time and expense for litigants seeking to bring, or defend against, special motions to dismiss and has placed an enormous burden on motion judges in their efforts to decide such motions. These pragmatic difficulties detract from one of the principal purposes of § 59H: to obtain the expeditious dismissal of meritless claims that are based on petitioning alone.

The nature, scope, duration, and complexity of the instant case exemplify the need to clarify and simplify decision-making in this area. It concerns various claims arising out of the unsuccessful efforts of the Todesca litigants (the defendants and proponents of the special motion to dismiss in this case), before various administrative and judicial bodies, to block the Bristol litigants (the plaintiffs and opponents of the special motion to dismiss) from obtaining approval to construct and operate an asphalt plant that would rival their own. After the last of these challenges failed in 2020, the Bristol litigants brought suit, asserting that the Todesca litigants' legal maneuvers amounted to abuse of process and violated G. L. c. 93A, §§ 4 and 11. In response, the Todesca litigants filed a special motion to dismiss under § 59H, asserting that their legal efforts to block a competitor's asphalt plant constituted a legitimate exercise of their right of petition under

Page 542

the First Amendment to the United States Constitution, for which they could not be sued. The special motion was denied, and the Todesca litigants pursued an interlocutory appeal. The matter is now before us three and one-half years after this lawsuit first began.

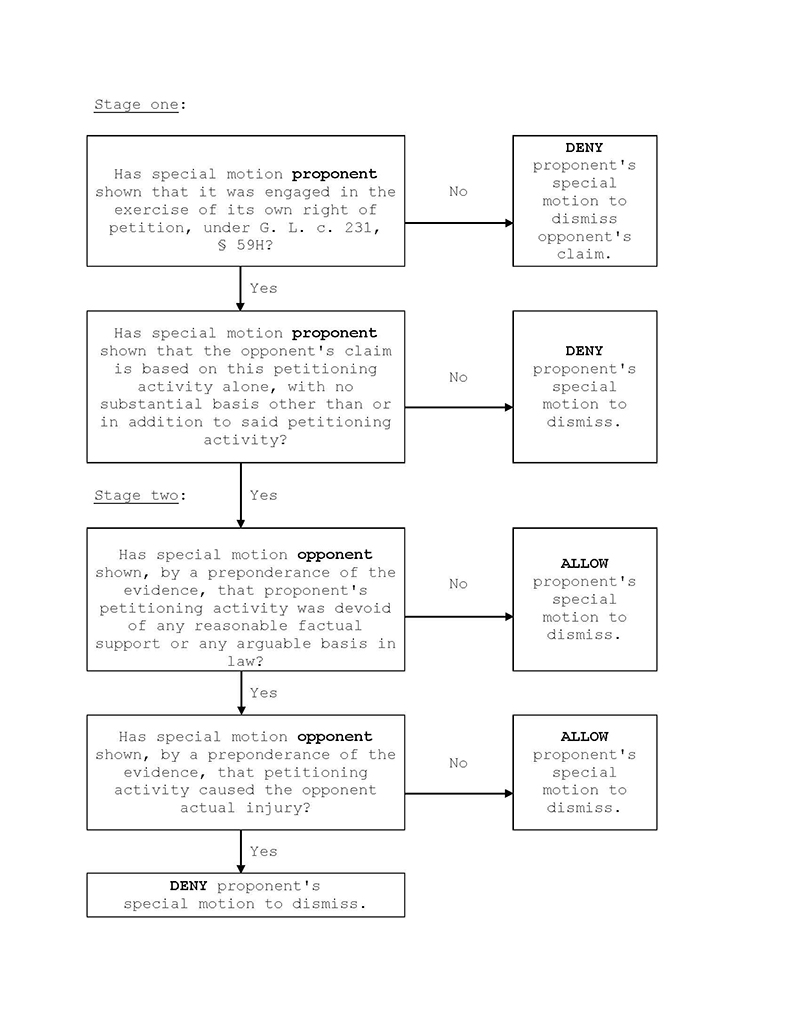

Recognizing that our existing framework for analyzing special motions to dismiss under § 59H has not provided an efficient or practical solution to the problem it was designed to address, we thus conclude that a simplification of our existing anti-SLAPP framework, and one that hews to the statutory language, is necessary to ensure that the legislative intent behind the statute is not undermined by its misapplication. Toward that end, we set forth a revised anti-SLAPP framework in the instant opinion, along with an Appendix designed to provide guidance on its practical administration.

Under this simplified anti-SLAPP framework, we eliminate the additional analysis set forth in Blanchard I and Blanchard II and return to the traditional approach set out in Duracraft. We also seek to provide more detail on how to determine whether petitioning activity is devoid of any reasonable factual support or arguable basis in law. Finally, we clarify that the appropriate standard of review for a ruling on a special motion to dismiss is de novo, rather than for an abuse of discretion. Applying this simplified framework to the instant case, we conclude that the Todesca litigants' petitioning activities were not entitled to the procedural protections of § 59H. [Note 4]

1. Factual background. We summarize the facts as derived from the pleadings and attached documentary evidence before the Superior Court, reserving certain facts for our discussion below. See G. L. c. 231, § 59H; Dickey v. Warren, 75 Mass. App. Ct. 585, 588 n.5 (2009), cert. denied, 560 U.S. 926 (2010).

The Todesca litigants -- the special motion proponents in the instant suit -- own and/or operate an asphalt plant at 83 Kings Highway in the town of Rochester (town), within an area that has

Page 543

been zoned for industrial uses since 1969. [Note 5] The area where the asphalt plant is located also houses a concrete block manufacturing plant, a building material deconstruction facility, and several waste facilities. The Bristol litigants �-- the special motion opponents in this suit -- are business competitors who sought to open their own asphalt plant on an adjacent parcel of land in the same industrial zone, beginning in late 2010. [Note 6] The Todesca litigants subsequently launched a series of administrative and legal challenges to the Bristol litigants' efforts to obtain regulatory approval for the construction and operation of the proposed plant. Each one is outlined, in turn, below.

a. Challenges to site plan approval. In late 2010, the Bristol litigants submitted a site plan review application to the town's planning board (planning board) for their proposed asphalt plant. On May 24, 2011, the planning board issued a unanimous written decision in which it determined that the proposed plant was a permitted use in the industrial district, and approved the site plan subject to forty-three conditions designed to regulate anticipated noise, dust, fumes, and visual and traffic impacts relating to the project. Paul Todesca and abutters to the site appealed from the planning board's decision to the town's zoning board of appeals (zoning board). The zoning board unanimously affirmed the site plan approval. Albert and Paul Todesca (Todescas), as trustees of Todesca Realty Trust, along with abutters, then pursued a further appeal in the Land Court, pursuant to G. L. c. 40A, § 17.

In the Land Court, the Todescas argued that the site plan approval did not comply with local bylaws because of the anticipated effect that the proposed plant would have on noise levels, property values, and traffic in the area. Upon the parties' cross motions for partial summary judgment concerning the Todescas'

Page 544

noise-related arguments, the Land Court judge ruled in favor of the Bristol litigants, concluding that the noise issue had reasonably been addressed by conditions contained within the site plan approval.

After a trial on the Todescas' remaining claims, the Land Court judge issued a written memorandum of decision containing various findings of fact and entered judgment in favor of the Bristol litigants. The judge concluded that the proposed asphalt plant constituted a permitted use in the industrial district and that the evidence did not "support a finding that there are problems with the site plan that have not been reasonably addressed or that require conditions beyond those" already imposed by the planning board.

Thereafter, the Appeals Court affirmed the judgment of the Land Court in an unpublished decision. [Note 7] See D'Acci v. Board of Appeals of Rochester, 91 Mass. App. Ct. 1118 (2017). Upon conducting de novo review of the issue disposed on summary judgment, the Appeals Court concluded that the noise conditions contained within the site plan approval had been reasonable and that partial summary judgment had been properly entered in favor of the Bristol litigants. See id. The Appeals Court further concluded that the Land Court judge did not err in ruling in favor of the Bristol litigants on the remaining claims because the asphalt plant was a permitted use in the industrial district and the conditions imposed by the planning board had been reasonable. In so doing, the Appeals Court observed, inter alia, that there was "no evidence to support the conclusion that the addition of the [Bristol litigants' asphalt plant] would cause property values across the industrial district to decrease," nor any evidence that the harms anticipated by the Todescas were "inherent to the [Bristol litigants' asphalt plant] in particular, 'as opposed to any other industrial use.'" Id.

b. Challenges to extension of order of conditions. As part of their efforts to obtain regulatory approval for the proposed asphalt plant, the Bristol litigants also filed a notice of intent with the town's conservation commission (commission), pursuant to the Wetlands Protection Act, G. L. c. 131, § 40, and a municipal wetlands bylaw. After holding public hearings on the matter, the commission issued an order of conditions approving the proposed asphalt plant, subject to at least twenty-six special conditions, in

Page 545

2011. [Note 8] In light of the delays in construction caused by the Todesca litigants' legal challenges to the site plan approval, the Bristol litigants sought a three-year extension of the order of conditions in 2018, pursuant to 310 Code Mass. Regs. § 10.05(8)(a) (2014). After conducting a public hearing, a site visit, and a review of aerial photographs, as well as soliciting input from the town's conservation agent, the commission voted unanimously to approve the extension request.

The Todesca litigants (specifically, Rochester Bituminous Products, Inc. [RBP]), along with other abutters, filed a complaint in the Superior Court seeking judicial review of the extension of the order of conditions, pursuant to G. L. c. 249, § 4. RBP argued that the commission erred in granting the extension request without first conducting a new delineation (i.e., assessment) of the boundaries of nearby wetlands or confirming that the prior delineation remained accurate, and without considering changes in the area since the original order of conditions had issued.

On the parties' cross motions for judgment on the pleadings, a judge in the Superior Court affirmed the decision of the commission. The judge concluded that "a review of the administrative record does not show [RBP], or anyone else, presented any evidence of changes to the area" and that there was "nothing in the administrative record to support a finding that any resource area delineation was no longer accurate." RBP filed a notice of appeal, and the Appeals Court affirmed on the same basis in an unpublished decision. See Rochester Bituminous Products, Inc. v. Conservation Comm'n of Rochester, 98 Mass. App. Ct. 1118 (2020). [Note 9]

c. Fail-safe petitions for MEPA review. While the challenges to the order of extension mentioned supra were still ongoing, Todesca Realty Trust also obtained signatures from town residents and, through counsel, submitted a so-called "fail-safe petition" requesting that the Executive Office of Energy and Environmental Affairs

Page 546

(EOEE) conduct a review of the proposed plant under the Massachusetts Environmental Policy Act, G. L. c. 30, §§ 61-62H (MEPA). [Note 10] The EOEE issued an order denying the fail-safe petition, concluding that it did not meet the regulatory standards for review under 301 Code Mass. Regs. § 11.04(1) (2008). Todesca Realty Trust subsequently filed a second fail-safe petition for MEPA review on January 22, 2020. The EOEE issued an order denying this petition as well, noting that it alleged "virtually identical facts" to the first, unsuccessful fail-safe petition.

2. Procedural history. On September 2, 2020, the Bristol litigants filed a three-count amended complaint against the Todesca litigants, alleging that the above-mentioned legal challenges constituted unfair or deceptive acts or practices in the conduct of trade or commerce, in violation of G. L. c. 93A, § 11; conspiracy in restraint of trade or commerce, in violation of G. L. c. 93A, § 4; and abuse of process. The Todesca litigants filed an answer, asserting the anti-SLAPP statute as an affirmative defense, and later filed a special motion to dismiss under G. L. c. 231, § 59H, or, in the alternative, a motion to dismiss under Mass. R. Civ. P. 12 (c), 365 Mass. 754 (1974), for failure to state a claim upon which relief may be granted. [Note 11] In support of the filing, the Todesca litigants attached an affidavit from Albert Todesca asserting that he had "good faith legal and factual bases" for each of the legal challenges that the Todesca litigants had pursued. The Bristol litigants filed an opposition, attaching two affidavits, along with over one hundred pages of exhibits, consisting of deposition excerpts and administrative and judicial decisions arising out of the prior legal challenges.

After a hearing, a judge in the Superior Court denied the special motion to dismiss. [Note 12] The motion judge acknowledged that all of the challenged claims sought to impose liability on the Todesca litigants based solely on their petitioning activities (i.e., their

Page 547

legal challenges to regulatory approval for the proposed asphalt plant). However, the motion judge went on to conclude that because the Todesca litigants' petitioning activities had been a "sham," they were not entitled to dismissal of the claims filed against them.

The Todesca litigants pursued an interlocutory appeal from the denial of their special motion to dismiss. See Fabre v. Walton, 436 Mass. 517, 521-522 (2002), S.C., 441 Mass. 9 (2004) (holding that litigants have right to pursue interlocutory appellate review from denial of special motion to dismiss). A majority of the Appeals Court affirmed the denial of the Todesca litigants' motion, after engaging in a detailed discussion and analysis of each one of the Todesca litigants' petitioning activities. See Bristol Asphalt Co. v. Rochester Bituminous Prods., Inc., 102 Mass. App. Ct. 522, 538 (2023).

In a separate opinion dissenting in part, a justice of the Appeals Court concluded that the Todesca litigants' challenge to the site plan approval was not a sham insofar as it was based on anticipated traffic impacts from the proposed asphalt plant. See id. at 541 (Englander, J., dissenting). The dissent further noted that it was error to review the resolution of a special motion to dismiss only for abuse of discretion, as the nature of the inquiry necessitated de novo review. Id. at 544. The dissent also highlighted other difficulties posed by our existing anti-SLAPP framework, particularly the additional analysis required by Blanchard I and Blanchard II. Id. at 547-548. We subsequently allowed the Todesca litigants' application for further appellate review.

3. Anti-SLAPP framework for assessing special motions to dismiss. a. Legislative history and development of current framework. [Note 13] The acronym "SLAPP," which stands for "Strategic Litigation Against Public Participation," was coined in the 1980s to

Page 548

refer to "meritless suits brought by large private interests to deter common citizens from exercising their political or legal rights or to punish them for doing so" (citations omitted). Duracraft, 427 Mass. at 160 n.7, 161. Although such suits may fail on the merits, they send a message to average citizens that the price for speaking out is "a multimillion-dollar lawsuit and the expenses, lost resources, and emotional stress such litigation brings." Pring, SLAPPs: Strategic Lawsuits Against Public Participation, 7 Pace Envtl. L. Rev. 3, 6 (1989). In response to growing concerns about large developers filing SLAPP suits to silence local residents, the Commonwealth enacted its own so-called anti-SLAPP statute, G. L. c. 231, § 59H. See Duracraft, supra at 161. The statute creates a procedural vehicle -- known as the special motion to dismiss -- intended to secure the early dismissal of a meritless SLAPP claim, along with attorney's fees, before significant discovery has occurred. Id. at 161-162.

The statute delineates the following procedure for filing and analyzing special motions to dismiss:

"In any case . . . in which a party asserts that the civil claims, counterclaims, or cross claims against said party are based on said party's exercise of its right of petition under the constitution of the United States or of the commonwealth, said party may bring a special motion to dismiss. The court shall advance any such special motion so that it may be heard and determined as expeditiously as possible. The court shall grant such special motion, unless the party against whom such special motion is made shows that: (1) the moving party's exercise of its right to petition was devoid of any reasonable factual support or any arguable basis in law and (2) the moving party's acts caused actual injury to the responding party. In making its determination, the court shall consider the pleadings and supporting and opposing affidavits stating the facts upon which the liability or defense is based."

G. L. c. 231, § 59H, first par. The statute goes on to define the phrase "a party's exercise of its right of petition," used in the above-quoted provision, to include

"any written or oral statement made before or submitted to a legislative, executive, or judicial body, or any other governmental proceeding; any written or oral statement made in

Page 549

connection with an issue under consideration or review by [such body]; any statement reasonably likely to encourage consideration or review of an issue by [such body]; any statement reasonably likely to enlist public participation in an effort to effect such consideration; or any other statement falling within constitutional protection of the right to petition government."

G. L. c. 231, § 59H, sixth par. As illustrated by the multitude of appellate cases interpreting § 59H since its enactment in 1994, the Legislature's broad conceptualization of petitioning and prioritization of its protection within this statutory formulation have led to a number of difficulties.

First, while the statute's applicability turns on the special motion proponent's constitutional rights of petition, the statute does not "rely solely on these rights, as defined by the United States Supreme Court or this court, to determine the scope of protected activity, and instead provides its own express -- and broad -- definition of 'petitioning.'" Commonwealth v. Exxon Mobil Corp., 489 Mass. 724, 727 n.3 (2022) (Exxon). See, e.g., Blanchard I, 477 Mass. at 150-151 (statements to newspaper about decision to fire nurses constituted petitioning under § 59H, because definition includes any statement made "in connection with" issue under consideration or review by governmental agency, and statements had been made in manner "that was likely to influence or, at the very least, reach" Department of Mental Health). Thus, a large body of case law has developed construing the meaning and scope of this statutory definition. See id. at 153 n.19 (collecting cases). And unlike many other States' anti-SLAPP statutes, this definition does not limit the applicability of the statute to matters of public concern. See Duracraft, 427 Mass. at 163 n.12. As a result, a party may seek to invoke the powerful protections of the anti-SLAPP statute to protect speech even if it "involves a commercial motive," with only a limited relationship to issues of public concern. See, e.g., North Am. Expositions Co. Ltd. Partnership v. Corcoran, 452 Mass. 852, 863 (2009) (attempts to persuade foundation not to sponsor competing events); Office One, Inc. v. Lopez, 437 Mass. 113, 122-123 (2002) (communications about purchase of condominium units owned by Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation). See also Kobrin v. Gastfriend, 443 Mass. 327, 331 (2005) (statute "applies to matters of both public and private concern"). This has "led to a

Page 550

significant expansion of [the statute's] application" beyond the original problem it aimed to correct. Exxon, supra at 728 n.5.

In addition to defining petitioning expansively, the statute goes on to immunize this broad category of conduct from suit, except where it is "devoid of any reasonable factual support or any arguable basis in law." G. L. c. 231, § 59H, first par. That is, unless the opponent to a special motion to dismiss can show that the petitioning activity was "devoid" of "any" reasonable basis in fact or law, the opponent's claims -- regardless of their underlying merits -- must be dismissed. Id. Indeed, the proponent of the special motion is presumptively entitled to dismissal of these claims, along with a mandatory award of attorney's fees. See id. Because this statutory test is focused exclusively on the petitioning activity, without considering whether there is support for the contentions put forward in the special motion opponent's claims, the statute "makes no provision for a [special motion opponent] to show that its own claims are not frivolous." Duracraft, 427 Mass. at 164-165. This approach differs from most States' anti-SLAPP statutes, which permit special motion opponents to defeat such a motion, and thereby preserve their claims, by demonstrating that their claims are likely to succeed on the merits. [Note 14] See id. at 166 n.18.

By failing to consider the merits of the claims that are subject to presumptive dismissal, § 59H raises a paradoxical conundrum that "has troubled judges and bedeviled the statute's application," and one that we highlighted in Duracraft: "[b]y protecting [the special motion proponent]'s exercise of its right of petition, unless it can be shown to be sham petitioning, the statute impinges on the [special motion opponent]'s exercise of its right to petition, even when it is not engaged in sham petitioning." Id. at 166-167.

To address this constitutional problem and paradox, in Duracraft we adopted a strict construction of § 59H's reference to claims "based on" a party's petitioning activity. Specifically, we

Page 551

construed the term "based on" so as to "exclude motions brought against meritorious claims with a substantial basis other than or in addition to the petitioning activities implicated." Id. at 167. Accordingly, our holding in Duracraft placed a threshold burden upon the proponent of a special motion to dismiss to show that each of the claims it was moving to dismiss had "no substantial basis other than or in addition to [its] petitioning activities." Id. at 167-168. The sufficiency of the special motion proponent's threshold showing was to be evaluated count by count. See Ehrlich v. Stern, 74 Mass. App. Ct. 531, 536 (2009). If a count was based substantially on conduct other than petitioning activity, it survived. See id. If, and only if, a count had no substantial basis other than petitioning did the burden then shift to the special motion opponent to demonstrate, per the statutory language, that its claim should not be dismissed because the petitioning activity forming the basis of the claim "was devoid of any reasonable factual support or any arguable basis in law" and caused it "actual injury." G. L. c. 231, § 59H. See Duracraft, supra.

In Blanchard I, 477 Mass. at 155-156, 159-161, and Blanchard II, 483 Mass. at 206-207, in an attempt to more precisely protect petitioning and more clearly permit other lawsuits not based on "classic" petitioning activity to proceed, this court chose to revisit the anti-SLAPP framework in two significant and complex ways. First, we held that a special motion proponent may seek to dismiss the portion of a special motion opponent's claim that is based on petitioning activity, so long as that petitioning activity could have independently served as the sole basis for the claim. See Blanchard I, supra at 155-156; Reichenbach v. Haydock, 92 Mass. App. Ct. 567, 574 (2017) (clarifying that revised threshold burden depends upon nature of claim and theory of liability). That is, while a claim based on a mix of petitioning and nonpetitioning activity would not be subject to a special motion to dismiss under our prior Duracraft framework, this court's holding in Blanchard I, supra at 155-156, now required that a claim based on both types of conduct be "carefully parsed" by the motion judge, with the portion based on petitioning activity subject to possible dismissal, while the remainder of the claim is allowed to proceed. See Haverhill Stem LLC v. Jennings, 99 Mass. App. Ct. 626, 634 (2021).

This change from the Duracraft framework called for motion judges to sift through each individual count, with an eye toward the type of claim at issue, in order to identify whether the petitioning

Page 552

activity could, standing alone, support the underlying cause of action. See Reichenbach, 92 Mass. App. Ct. at 574. Doing so has proven to be a difficult and onerous task, and one that is not a traditional judicial function, as judges are not ordinarily expected to redraft parties' pleadings. See, e.g., id. at 575-576. See also Mmoe v. Commonwealth, 393 Mass. 617, 620 (1985) (observing that "[p]leadings must stand or fall on their own," as courts do not have "the power to fashion procedures in disregard of the Massachusetts Rules of Civil Procedure"); Granahan v. Commonwealth, 19 Mass. App. Ct. 617, 620 (1985). This difficulty remains even where the factual allegations are relatively simple, as the analysis called for under Blanchard I may vary depending on the nature of the claim at issue and the theory of liability advanced in the complaint. See Reichenbach, supra.

The second major change set forth in Blanchard I, 477 Mass. at 159-161, articulated an alternative means by which a special motion opponent could defeat the special motion, and has proven to be even more difficult to apply and controversial in its application. See Nyberg v. Wheltle, 101 Mass. App. Ct. 639, 654-655 (2022). Under this so-called "second path," the opponent must show, "such that the motion judge may conclude with fair assurance," that the opponent's claims are "colorable" and were not raised for the primary purpose of chilling the special motion proponent's legitimate petitioning activity. Blanchard I, supra at 160-161. Making this determination "rests within the exercise of the judge's sound discretion" and is reviewed for an abuse of discretion or error of law. Blanchard II, 483 Mass. at 203, 207.

In assessing an opponent's showing under this second path, we stated that "the judge may consider whether the case presents as a 'classic' or 'typical' SLAPP suit, i.e., whether it is a 'lawsuit[ ] directed at individual citizens of modest means for speaking publicly against development projects'" (citation omitted). Id. at 206. We also identified numerous other factors that may be relevant:

"by way of example, whether the lawsuit was commenced close in time to the petitioning activity; whether the anti-SLAPP motion was filed promptly; the centrality of the challenged claim in the context of the litigation as a whole, and the relative strength of the [special motion opponent]'s claim; evidence that the petitioning activity was chilled; and whether the damages requested by the [special motion opponent], such as attorney's fees associated with an abuse of

Page 553

process claim, themselves burden the [special motion proponent]'s exercise of the right to petition" (footnotes omitted).

Id. at 206-207.

As demonstrated by the briefing in this appeal, the submissions from all the amici, and the feedback by way of recent jurisprudence from appellate justices concerning the second path, it has become clear that the second path presents numerous problems. It strays from the statutory language. See G. L. c. 231, § 59H. It shifts the focus to the motives of the special motion opponent, which must be determined based on documentary evidence alone. See Nyberg, 101 Mass. App. Ct. at 654-655 (pointing out difficulty motion judge will have "discern[ing] a party's primary motivation" for bringing suit, on basis of documentary evidence alone, and without "a more complete evidentiary record scrutinized through cross-examination"). And it involves consideration of an open-ended list of factors, thereby inviting subjective, if not unpredictable, decision-making. See, e.g., id. at 656 (upholding allowance of special motion to dismiss, despite observing that "a different judge may have reached a different result" in conducting "second path" analysis).

This additional complexity further serves to lengthen the amount of time it takes for parties to litigate a special motion to dismiss, and for motion judges to rule on them. See Krimkowitz v. Aliev, 102 Mass. App. Ct. 46, 47 (2022) ("Typically, rulings on special motions to dismiss under the anti-SLAPP statute run many pages and require difficult legal analysis"). Thus, the resolution of these motions may span years and result in significant attorney's fees. See Exxon, 489 Mass. at 728 n.5, and cases cited. All the while, discovery in the case is automatically stayed. See G. L. c. 231, § 59H, third par. And because the statute requires that the resolution of such motions must be prioritized, the current anti-SLAPP framework has a significant impact on a trial court's ability to manage its docket in an orderly and efficient manner. See Exxon, supra. In short, while special motions to dismiss were designed to "be resolved quickly with minimum cost to citizens who have participated in matter of public concern," resolution under the augmented framework has become anything but. Duracraft, 427 Mass. at 161, quoting 1994 House Doc. No. 1520. Accordingly, for all these reasons we eliminate the second path set out in Blanchard I and Blanchard II.

We also overrule the additional requirement set forth in Blanchard I, 477 Mass. at 155-156, and further explicated in

Page 554

Reichenbach, 92 Mass. App. Ct. at 574, that the motion judge parse the factual allegations underlying each claim to determine whether a portion of the opponent's cause of action could be construed as being based on the proponent's petitioning alone. We begin with the recognition that "the statute does not create a process for parsing counts to segregate components that can proceed from those that cannot." Ehrlich, 74 Mass. App. Ct. at 536. Engaging in such parsing has likewise significantly complicated and delayed the resolution of these cases. Furthermore, as this court cautioned in Duracraft, 427 Mass. at 166-167, we must always be aware that both proponents and opponents of special motions to dismiss are engaged in petitioning activity, requiring courts to proceed cautiously when the protection of a proponent's petitioning activity interferes with an opponent's own legitimate petitioning rights. [Note 15]

Mixed claims, that is, those based on a proponent's petitioning along with substantial conduct other than or in addition to the petitioning activities, inevitably involve an inquiry into both sides' legitimate petitioning rights. See id. And any citizen, including an opponent of a special motion to dismiss, certainly has a right to sue over matters not involving the proponent's petitioning rights. Such suits are exercises of the opponent's own right of petition. See Sahli v. Bull HN Info. Sys., Inc., 437 Mass. 696, 700-701 (2002). Thus, as we explain in more detail below, the parsing of claims involving a mixture of petitioning and other matters is best addressed in the course of ordinary litigation, where both sides' claims and defenses can be fully analyzed based on a more complete record, not special motions to dismiss.

b. Simplified anti-SLAPP framework. As we seek to clarify the anti-SLAPP framework, we recognize, as always, that our primary duty is to effectuate the intent of the Legislature. See Exxon, 489 Mass. at 726. We seek to discern this intent, in the first instance, from the words contained in the statute, "construed by the ordinary and approved usage of the language, considered in connection with the cause of its enactment, the mischief or imperfection to be remedied and the main object to be accomplished" (citation omitted). Id. At the same time, a statute must be

Page 555

construed, "when possible, to avoid unconstitutionality, and to preserve as much of the legislative intent as is possible in a fair application of constitutional principles" (citation omitted). Duracraft, 427 Mass. at 167.

i. Stage one: scope of applicability of special motion to dismiss. As is apparent from the plain language of § 59H, the special motion to dismiss is strong medicine. It offers a party the prospect of having the claims filed against it dismissed -- regardless of the merits of those claims and regardless that the filing of those claims is itself a petitioning activity -- as well as a mandatory award of attorney's fees, under a very favorable statutory standard: presumptive entitlement to dismissal, unless the opposing party can prove a negative. See G. L. c. 231, § 59H ("The court shall grant such special motion, unless the party against whom such special motion is made shows that . . . the moving party's exercise of its right to petition was devoid of any reasonable factual support or any arguable basis in law . . ."). And irrespective of the outcome, the mere act of filing the special motion stays discovery and prioritizes resolution of the motion over the rest of the case. See id.

We thus conclude, as we originally did in Duracraft, 427 Mass. at 166-168, that these powerful procedural protections were intended to be employed in a limited context: to ensure the expeditious elimination of meritless lawsuits based on petitioning activities alone. To prevent the misapplication of § 59H, this court in Duracraft adopted a necessarily narrow and strict construction of the statute, which we return to today. In particular, the narrow construction of the term "based on" articulated in Duracraft appropriately established a threshold showing that remains a necessary part of a simplified anti-SLAPP framework, and ensures that an opponent's own petitioning activity is not infringed by the allowance of a special motion to dismiss. See id. at 167.

Accordingly, under the simplified framework we set forth today (and as was the case prior to Blanchard I), a proponent of a special motion to dismiss under § 59H must "make a threshold showing through the pleadings and affidavits that the claims against it are 'based on' the [party's] petitioning activities alone and have no substantial basis other than or in addition to the petitioning activities." Id. at 167-168. Thus, to survive this first stage, the proponent must show that the challenged count has no substantial basis in conduct other than or in addition to the special

Page 556

motion proponent's alleged petitioning activity. If the proponent cannot make the requisite threshold showing, the special motion to dismiss is denied. If the threshold showing is made, the second stage of analysis follows (more on this below).

Importantly, this return to the traditional analysis at the threshold stage does not mean that a special motion proponent will be held liable for exercising his or her constitutional right to engage in legitimate petitioning activity merely because the special motion opponent advances a claim that is based only in part on said petitioning activity. Such petitioning may still be entitled to protection from liability under the State and Federal Constitutions [Note 16] as the case proceeds according to the ordinary litigation process. See Sahli, 437 Mass. at 702-703 (concluding, upon review of summary judgment ruling, that "although the interest in remedying discrimination is weighty, it is not so weighty as to justify what amounts to an absolute restriction on an employer's right to petition the courts"). See also Professional Real Estate Investors, Inc. v. Columbia Pictures Indus., Inc., 508 U.S. 49, 57 (1993) (holding that petitioning activity with objectively reasonable basis is immunized from antitrust liability). Cf. Snyder v. Phelps, 562 U.S. 443, 451-452, 458 (2011) (defendants could not be held civilly liable for picketing because statements involved matter of public concern and were therefore entitled to special protection under free speech clause of First Amendment).

Rather, returning to the traditional Duracraft analysis at the threshold stage, which denies special motions to dismiss for claims that have a substantial basis in addition to petitioning activity, and addresses the legitimacy of the petitioning activity implicated therein later on, in the ordinary course of litigation, simply ensures that the incredibly powerful procedural protections of the special motion to dismiss are appropriately reserved for the narrow category of meritless SLAPP claims that the Legislature sought to target -- namely, those based solely on legitimate petitioning activity. See Ehrlich, 74 Mass. App. Ct. at 537. [Note 17] Such an approach better serves to eliminate meritless SLAPP claims quickly, "removes the unwarranted intimidation or

Page 557

punishment produced by the claim's very existence," and "leaves to substantive law," and the ordinary course of litigation, "the task of sorting out rights and responsibilities bound up in any surviving counts." Id.

ii. Stage two: standard for determining whether special motion opponent has met burden to defeat special motion to dismiss. Where a special motion proponent has met this threshold burden, the statute requires allowance of the special motion to dismiss, "unless the [special motion opponent] shows" that the special motion proponent's exercise of its right of petition "was devoid of any reasonable factual support or any arguable basis in law" and (2) "caused actual injury to the [special motion opponent]." G. L. c. 231, § 59H. We have thus far provided relatively limited guidance on the practicalities of how to determine whether petitioning activity is devoid of any reasonable factual support or any arguable basis in law when assessing a special motion to dismiss. See 477 Harrison Ave., LLC v. Jace Boston, LLC, 477 Mass. 162, 173 (2017) (Harrison), S.C., 483 Mass. 514 (2019) (characterizing determination as "little-discussed second-stage burden").

We begin with the recognition that proving petitioning is "devoid" of any reasonable factual support or any arguable basis in law is a difficult task and one that the statute imposes on the special motion opponent. In Baker v. Parsons, 434 Mass. 543, 553-554 (2001), we expressly held that the special motion opponent "is required to show by a preponderance of the evidence that the [special motion proponent] lacked any reasonable factual support or any arguable basis in law for its petitioning activity." The difficulty of making this showing was further clarified in Benoit v. Frederickson, 454 Mass. 148, 149-151 (2009), where the petitioning activity consisted of the reporting of an alleged rape to police, and the record contained competing affidavits as to whether the rape had, in fact, occurred. In discussing the nature of the special motion opponent's burden, we explained:

"The question to be determined by a judge in deciding a special motion to dismiss is not which of the parties' pleadings and affidavits are entitled to be credited or accorded greater weight, but whether the [special motion opponent] has met its burden (by showing that the underlying petitioning

Page 558

activity by the [special motion proponents] was devoid of any reasonable factual support or arguable basis in law, and whether the activity caused actual injury to the [special motion opponent])."

Id. at 154 n.7. We emphasized that the "mere submission of opposing affidavits by the [special motion opponent] could not," in this case involving conflicting affidavits as to whether a rape had occurred, "have established that the [special motion proponents'] petitioning activity," i.e., her report of the rape to police, was devoid of any reasonable factual support or any arguable basis in law. See id. [Note 18] See also Blanchard I, 477 Mass. at 156 n.20 (proving that petitioning activity was illegitimate presents "high bar" for special motion opponent).

As material, disputed credibility issues may not be resolved in the special motion opponent's favor, see Baker, 434 Mass. at 553, the evidentiary support in favor of the special motion proponent's petitioning activity must be quite limited in order for a special motion opponent to satisfy the "devoid of any reasonable factual support" standard. The legal basis for a special motion proponent's petitioning activity likewise need only be "arguable." See G. L. c. 231, § 59H.

That being said, when the special motion opponent has submitted evidence and argument challenging the reasonableness of the factual and legal basis of the petitioning, a special motion proponent cannot merely rely on speculation, conclusory assertions, or averments outside of its personal knowledge for the court to identify reasonable support. See, e.g., Gillette Co. v. Provost, 91 Mass. App. Ct. 133, 138 (2017) (no reasonable basis where special motion opponent provided detailed evidentiary support, and, "[t]o counter [opponent's] evidentiary proffer, [proponent] submitted a single declaration" with conclusory assertion that petitioning activity had been filed for legitimate, good-faith purpose).

The cases in which we have determined that no reasonable factual support or arguable legal basis existed for the petitioning provide helpful guidance on this point. In Harrison, 477 Mass. at 174, for example, this court held that there was no reasonable

Page 559

basis for an application for a criminal complaint alleging trespass where the complaint was dismissed for lack of probable cause and had been filed "after a Superior Court judge explicitly granted the [special motion opponent] the affirmative right to trespass on the [special motion proponent's] property to protect it from damage." We determined that "[t]he combination of the lack of probable cause finding and the Superior Court order supplies the requisite preponderance of the evidence in favor of the conclusion that the criminal complaint lacked any reasonable basis in fact or law." Id.

We reached a similar conclusion in Van Liew v. Stansfield, 474 Mass. 31, 39-40 (2016), where the special motion proponent's petitioning activity consisted of an application for a harassment prevention order. Because this application did not contain three or more acts of harassment, as required under G. L. c. 258E, §§ 1 and 3, the special motion proponent was not entitled to issuance of the harassment prevention order. [Note 19] As a result, and as the special motion opponent showed in accordance with his burden to do so, we concluded that the petitioning activity (i.e., the application for a harassment prevention order) was "devoid of any reasonable factual support or any arguable basis in law." Id. at 39, quoting G. L. c. 231, § 59H.

Various other cases provide additional examples of this analysis. See Gillette Co., 91 Mass. App. Ct. at 138-139; Maxwell v. AIG Dom. Claims, Inc., 72 Mass. App. Ct. 685, 696 (2008) (no reasonable factual support for allegation of workers' compensation fraud was provided by innocuous observations or assertions that "record shows was flatly incorrect"); Garabedian v. Westland, 59 Mass. App. Ct. 427, 434 (2003) (special motion proponents' efforts to prevent special motion opponent from bringing fill onto his land were devoid of reasonable factual support or arguable legal basis where there "was no showing of a basis, in the by-laws of Southborough or elsewhere, to regulate the kind of land filling" that opponent was conducting).

Analogous case law is also informative on how to apply the no "reasonable factual support or arguable basis in law" standard. Most notably, our jurisprudence has tended to "equate the

Page 560

standard under the anti-SLAPP statute with the concept of frivolousness." Demoulas Super Mkts., Inc. v. Ryan, 70 Mass. App. Ct. 259, 267 (2007), and cases cited ("Though we acknowledge that the two statutory standards are not linguistic mirrors of each other, we are persuaded that they resolve the same essential question"). And as we explained in Fronk v. Fowler, 456 Mass. 317, 329 (2010), "[a] claim is frivolous if there is an absence of legal or factual basis for the claim, and if the claim is without even a colorable basis in law" (quotations and citations omitted). [Note 20] Compare Baker, 434 Mass. at 555 n.20, citing Donovan v. Gardner 50 Mass. App. Ct. 595, 600 (2000) (mere fact that petitioning activity was not resolved in special motion proponent's favor "does not mean no colorable basis existed" to support petitioning). Cf. Marengi v. 6 Forest Rd. LLC, 491 Mass. 19, 29-30 (2022) (construing bond provision, which prohibits award of costs "unless" court determines appellant "acted in bad faith or with malice" in bringing appeal, to require showing that appeal "appears to be so devoid of merit as to allow the reasonable inference of bad faith or malice" [citation omitted]).

iii. Standard of review. Finally, we take this opportunity to clarify the appropriate standard of review on appeal. Although we have previously stated, in passing, that rulings on special motions to dismiss are reviewed for an abuse of discretion or error of law, see Baker, 434 Mass. at 550; McLarnon v. Jokisch, 431 Mass. 343, 348 (2000), subsequent decisions have effectively engaged in de novo review, at least as to the special motion proponent's threshold burden, see Reichenbach, 92 Mass. App. Ct. at 572; Blanchard v. Steward Carney Hosp., Inc., 89 Mass. App. Ct. 97, 112-113 (2016) (Sullivan, J., concurring in the result), S.C., 477 Mass. 141 (2017), and 483 Mass. 200 (2019), and cases cited. We now conclude that de novo review is required for both stages of our inquiry. We do so because both stages of our framework require resolution of legal questions based entirely on a documentary record, for which "no special deference" is owed to a motion judge. Board of Registration in Med. v. Doe, 457 Mass. 738, 742 (2010). Cf. Dartmouth v. Greater New Bedford Regional Vocational Tech. High Sch. Dist., 461 Mass. 366, 373 (2012).

Page 561

At the first stage, a court need only conduct a facial review of a special motion opponent's pleading to identify which factual allegations serve as the basis for a particular claim. [Note 21] Compare Dartmouth, 461 Mass. at 373 ("In reviewing the allowance of a motion to dismiss under Mass. R. Civ. P. 12 [b] [6], we examine the same pleadings as the motion judge and therefore proceed de novo"), with Reichenbach, 92 Mass. App. Ct. at 572 ("Because the first stage of the Duracraft analysis is, like the analysis of an ordinary motion to dismiss . . . directed to examining the allegations of the complaint, our review is fresh and independent, i.e., de novo" [quotation and citation omitted]).

At the second stage, a motion judge likewise relies on a documentary record, without resolving credibility disputes, and thus, as with the first stage, no deference is required. See Doe, 457 Mass. at 742. Cf. Adams v. Schneider Elec. USA, 492 Mass. 271, 288-289 (2023) (rulings on motions for summary judgment are subject to de novo review, requiring court to "determine judgment as a matter of law based on all uncontested evidence, that is, evidence favoring the nonmovant and 'uncontradicted and unimpeached' evidence favoring the movant").

Both stages thus involve application of a legal standard to documentary evidence alone. See Harrison, 477 Mass. at 176 n.15 (ruling on special motion to dismiss, which concerns whether petitioning activity "falls within the protective ambit of the anti-SLAPP statute," presents question of law). This is a decision ordinarily subject to de novo appellate review. See Robinhood Fin. LLC v. Secretary of the Commonwealth, 492 Mass. 696, 707 (2023) (questions of law are subject to de novo review on appeal). See also Commissioner of Revenue v. Comcast

Page 562

Corp., 453 Mass. 293, 302 (2009). [Note 22] The substantive legal questions being decided are also not comparable to prototypical examples of issues that we review for an abuse of discretion, such as the resolution of evidentiary decisions, or trial management judgment calls. See, e.g., Matter of Brauer, 452 Mass. 56, 73 (2008) (decision whether to grant continuance generally lies within sound discretion of trial judge); Carrel v. National Cord & Braid Corp., 447 Mass. 431, 446 (2006) (general evidentiary determinations, such as whether evidence is relevant or whether danger of unfair prejudice substantially outweighs its probative value, are questions left to sound discretion of trial judge); Goldstein v. Gontarz, 364 Mass. 800, 814 (1974) ("Permission to use a blackboard as a graphic aid is discretionary with the trial judge . . ."). Accordingly, we conclude that rulings on anti-SLAPP motions are appropriately subject to de novo review.

4. Application of simplified anti-SLAPP framework to instant case. Having clarified the relevant standards for our anti-SLAPP framework going forward, we now apply it to the circumstances of the instant case.

a. Todesca litigants' threshold burden. Here, there is no dispute that the special motion proponents in this case, the Todesca litigants, have met their threshold burden. All of the claims at issue are based solely on the Todesca litigants' administrative and legal challenges to regulatory decisions approving the Bristol litigants' proposed asphalt plant. [Note 23] This is quintessential petitioning activity. See Duracraft, 427 Mass. at 161-162; Dever v. Ward, 92 Mass. App. Ct. 175, 179 (2017).

The Bristol litigants do not contest this, but argue that the anti-SLAPP statute should nonetheless be deemed inapplicable because the Todesca litigants are not citizens of modest means,

Page 563

but business competitors who have invoked the special motion to dismiss as one additional strategic tactic in a larger series of anticompetitive legal maneuvers. However, neither a special motion proponent's identity, nor the motive behind its decision to engage in petitioning activity (or to file a special motion to dismiss), is relevant to the threshold inquiry. See Office One, Inc., 437 Mass. at 121-122.

b. Bristol litigants' burden to show petitioning activity was devoid of reasonable support. Because the Todesca litigants met their threshold burden, we now consider whether the Bristol litigants have shown by a preponderance of the evidence that the petitioning activities lacked any reasonable factual support or arguable legal basis. See G. L. c. 231, § 59H. We assess each petitioning activity in turn.

i. Legitimacy of challenges to site plan approval. We first consider the basis for the Todescas' challenges to the site plan approval. To meet their burden as special motion opponents, the Bristol litigants provided the motion judge with the memorandum of decision of the Land Court as well as the unpublished decision of the Appeals Court concerning the site plan approval. Looking to the contents of these materials, they reveal that the Todescas' challenges were premised upon two legal theories: (1) that the proposed asphalt plant did not constitute a use that was permitted "as of right" in the industrial district; and (2) that, regardless of whether the asphalt plant was permitted as of right, operation of the plant would create problems so significant as to violate the standards for site plan approval under the town's zoning bylaws.

A. Arguments that proposed asphalt plant was not use permitted as of right in industrial district. We evaluate the Todescas' first basis for challenging the site plan approval -- the contention that the asphalt plant was not a use permitted as of right -- by turning to the applicable town zoning bylaw. As indicated, the proposed site of the asphalt plant was located within an industrial district, which the bylaws define as permitting the following uses as of right: "[m]anufacturing, industrial or commercial uses including processing, fabrication, assembly and storage of materials," provided that "no such use is permitted which would be detrimental or offensive or tend to reduce property values in the same or adjoining district." Rochester bylaws § IV(D)(1), as amended May 18, 2009. Accordingly, an industrial use of the land would not be considered a use permitted "as of right" under this definition if such a use would necessarily carry with it effects that

Page 564

are "detrimental," "offensive," or tending to reduce property values in the area.

The Land Court judge's memorandum of decision indicates that the Todescas presented "no evidence" of any detrimental or offense effects "inherent in an asphalt plant use as opposed to any other industrial use" (emphasis in original). Nor did the Todescas present "any evidence" that an asphalt plant would tend to reduce property values in the industrial district, or in an adjoining district. Indeed, the Todescas' own asphalt plant was approved under the very same bylaws in the very same industrial district, on an adjacent parcel of land. And, as the Land Court judge noted, there was "no evidence that the Asphalt Plant proposed by [the Bristol litigants] would be appreciably different, or more intense in character," than any of the existing industrial uses in the area, including the operation of Todescas' own asphalt plant. To the contrary, "the evidence indicate[d] that the [Bristol litigants'] proposed Asphalt Plant would be a smaller and less intense bituminous processing use" than the Todescas' neighboring plant. Accordingly, we conclude, as did the Appeals Court, that this challenge to the site plan approval was advanced without reasonable factual support or an arguable legal basis. See SCIT, Inc. v. Planning Bd. of Braintree, 19 Mass. App. Ct. 101, 105 n.12 (1984) ("if the specific area and use criteria stated in the by-law were satisfied, the board did not have discretionary power to deny a permit, but instead was limited to imposing reasonable terms and conditions on the proposed use").

B. Arguments that, insofar as use was permitted as of right, site plan nonetheless violated applicable bylaws. The remaining basis for the Todescas' challenge was the theory that, even to the extent that the site plan involved a use permitted as of right in the industrial district, the proposed asphalt plant would create noise and traffic problems so significant as to necessitate denial of the site plan under the town's zoning bylaws. See Prudential Ins. Co. of Am. v. Board of Appeals of Westwood, 23 Mass. App. Ct. 278, 283 (1986) (where site plan approval involved use permitted as of right, inquiry was limited to whether proposal created problem that was "so intractable that it could admit of no reasonable solution"). To evaluate whether this argument was colorable, we look first to the applicable bylaws governing site plan approval and denial.

The town's zoning bylaws specify that site plans involving building construction shall be designed, inter alia, to "[m]aximize

Page 565

pedestrian and vehicular safety both on the site and egressing from it" and "[c]onform with State and local sound regulations." Rochester bylaws § XVI(1.4)(7),(14), as amended Oct. 24, 2005. The bylaws further authorize the planning board to impose conditions to ensure that these considerations "have been reasonably addressed" by the site plan applicant. Id. A site plan will be denied if it "has not met these standards for review and reasonably addressed the conditions" contained therein, or is otherwise "so intrusive on the needs of the public in one regulated aspect or another" that "no form of reasonable conditions can be devised to satisfy the problem with the [site] plan." Rochester bylaws § XVI(1.3)(3),(4), as amended Oct. 24, 2005.

With regard to noise, the Todescas supplied a study they had commissioned from a private consultant that projected that the plant would generate noise levels in excess of State regulations. With regard to traffic, the Todescas offered testimony, from an expert who had never previously studied the operations of a bituminous facility, that it was possible a queue of up to seven trucks could develop in the driveway of the asphalt plant. Based on an assumption supplied by the Todescas that every truck entering the site would be fifty-two feet long, rather than an independent study of proposed site conditions, the expert opined that the last truck in the queue would spill over onto Kings Highway, "causing a potentially unsafe traffic condition." The expert further opined that the Bristol litigants' plan for addressing possible spillover by maneuvering trucks to the rear of the site was "unworkable."

The question now before us is whether this amounted to reasonable factual support or an arguable legal basis for challenging the site plan approval. We conclude that it did not. Here, the planning board's approval of the site plan was already squarely conditioned on addressing the very concerns about noise and traffic that the Todescas later asserted had not been, and could not be, reasonably addressed. The planning board not only conditioned site plan approval on the requirement that the asphalt plant comply with State and local noise restrictions, but also required that the Bristol litigants hire a noise monitoring consultant to submit seasonal reports to ensure compliance. Further, irrespective of the testimony offered by the Todescas' expert that the queue of driveway traffic could potentially result in one truck lacking sufficient space to join the queue on the property, which was based on unsupported assumptions, the planning board had

Page 566

already conditioned approval of the site plan on prohibiting trucks from parking along Kings Highway. The planning board further required that the Bristol litigants "coordinate with the [t]own to install the necessary signage to enforce this restriction," along with imposing numerous other traffic-related conditions. [Note 24] Thus, even assuming, arguendo, that a single truck found itself unable to enter the driveway, it would not be permitted to idle on Kings Highway, obviating the basis for the Todescas' contention about an "intractable" traffic problem. See Prudential Ins. Co. of Am., 23 Mass. App. Ct. at 283.

Finally, while the bylaws contemplate that a site plan may be denied if an applicant has not "reasonably addressed the conditions" imposed by the planning board, there is nothing in the memorandum of decision by the Land Court or the unpublished decision by the Appeals Court to indicate that the Todescas presented any evidence suggesting that the Bristol litigants would not or could not comply with the above-mentioned conditions imposed by the board. The only additional evidence we have before us, offered by the Todesca litigants in support of their special motion to dismiss, is Albert Todesca's affidavit stating that he had "good faith legal and factual bases" for challenging the site plan approval. This conclusory averment fails to supply reasonable factual support. See Gillette Co., 91 Mass. App. Ct. at 138. Accordingly, the Bristol litigants have met their burden of showing that this petitioning activity was a sham. See Garabedian, 59 Mass. App. Ct. at 434.

ii. Legitimacy of challenges to extension of order of conditions. Next, we examine the legal challenges to the extension of the order of conditions for the proposed asphalt plant. The regulatory authority to extend or deny an order of conditions is set forth in 310 Code Mass. Regs. § 10.05(8). Pursuant to that provision, the commission "may deny the request for an extension" in one of five enumerated circumstances. See 310 Code Mass. Regs. § 10.05(8)(b). The record before us indicates that RBP provided no evidence as to the presence of any of the five circumstances set

Page 567

forth in § 10.05(8)(b). RBP's assertion that the commission retained the authority to deny the extension request even if none of these circumstances applied -- without identifying any legal source from which this authority would derive -- did not constitute an "arguable legal basis" for challenging the commission's decision to extend the order of conditions. Cf. Fronk, 456 Mass. at 335 ("Claims that are so unmoored from law or fact are the very definition of 'frivolous' . . ."). The Bristol litigants have thus met their burden of showing that this petitioning activity was a sham as well. [Note 25]

iii. Legitimacy of fail-safe petitions. Finally, we address the two fail-safe petitions filed by the Todesca litigants under 301 Code Mass. Regs. § 11.04(1). [Note 26] The applicable regulation permits ten or more citizens to file a petition requesting "fail-safe review" of a project that does not otherwise meet or exceed any thresholds for MEPA review, provided certain requirements are met. See id. The decision whether to grant such a request is left to the discretion of the Secretary of Energy and Environmental Affairs. See id. (Secretary "may require" MEPA review upon making certain findings). See also Ten Persons of the Commonwealth v. Fellsway Dev. LLC, 460 Mass. 366, 376 (2011) (citing 301 Code Mass. Regs. §§ 11.03 and 11.04 as regulations that call for Secretary to make "a purely discretionary determination"). Thus, the mere fact that a fail-safe petition was denied, without more, would not signify that it lacked legitimacy. See Wenger v. Aceto, 451 Mass. 1, 7 (2008). Nonetheless, the Bristol litigants have sustained their burden in the circumstances of the instant case.

A fail-safe petition for MEPA review is required to "state with specificity the Project-related facts" that the Todesca litigants believe warrant MEPA review, including facts indicating that such review is "essential to avoid or minimize Damage to the

Page 568

Environment." 301 Code Mass. Regs. § 11.04(1). Far from doing so, the first fail-safe petition relied on vague assertions that the proposed plant would exacerbate the negative impacts of other, unspecified "development in the area." By failing to provide support that could meet the relatively low threshold requirements of 301 Code Mass. Regs. § 11.04(1), the first fail-safe petition lacked a reasonable basis. It is readily apparent that this was also the case for the second fail-safe petition, which, apart from identifying an existing incineration facility in the area, relied on "virtually identical" assertions as the first petition. Accordingly, neither fail-safe petition constituted legitimate petitioning activity. [Note 27]

5. Conclusion. The denial of the Todesca litigants' special motion to dismiss is affirmed, and the matter is remanded to the Superior Court for further proceedings consistent with this opinion.

So ordered.

Page 569

BRISTOL ASPHALT, CO., INC., & another [Note 1] vs. ROCHESTER BITUMINOUS PRODUCTS, INC., & others. [Note 2]

BRISTOL ASPHALT, CO., INC., & another [Note 1] vs. ROCHESTER BITUMINOUS PRODUCTS, INC., & others. [Note 2]

------------------

------------------