DON PERRY vs. ZONING BOARD OF APPEALS OF HULL & others. [Note 1]

DON PERRY vs. ZONING BOARD OF APPEALS OF HULL & others. [Note 1]

Zoning, Appeal, By-law, Building permit, Frontage, Lot. Way, Private. Practice, Civil, Zoning appeal.

In a civil action challenging the issuance of a building permit to the owners of property abutting the plaintiff's property, a Land Court judge properly affirmed the decision of the town zoning board of appeals (board) upholding the issuance of the permit, where the board reasonably construed the town's zoning bylaw (bylaw) to distinguish between how frontage on a public street and frontage on a private way were calculated [21-23], where the owners had sufficient frontage to build the house (i.e., the bylaw required that the frontage be measured in linear feet but did not require the frontage to be straight) [23-24], where the locus met the bylaw's definition of a lot (i.e., it was bounded on all sides by lots) [24], where there was no error in treating the locus as a single lot [24-25], and where nothing in the bylaw required compliance with the Subdivision Control Law, G. L. c. 41, §§ 81K-81GG [25]; finally, this court declined to consider an issue for which the plaintiff failed to provide a record to support the factual assertions that formed the basis of his claims [25].

CIVIL ACTION commenced in the Land Court Department on July 10, 2018.

The case was heard by Michael D. Vhay, J., on motions for summary judgment.

Don Perry, pro se.

Adam J. Brodsky for Charles Williams & another.

James B. Lampke for zoning board of appeals of Hull & another.

DITKOFF, J. The plaintiff, Don Perry, appeals from a judgment of the Land Court affirming the decision of the zoning board of appeals (board) of the town of Hull (town), allowing the defendants, Anne Veilleux and Charles Williams (owners), to build a

Page 20

house on property (locus) abutting Perry's property. As the board reasonably construed the town's zoning bylaw (bylaw) to distinguish between how frontage on a public street and frontage on a private way is calculated, we conclude that the owners have sufficient frontage to build the house. Further concluding that Perry's other arguments lack merit, we affirm.

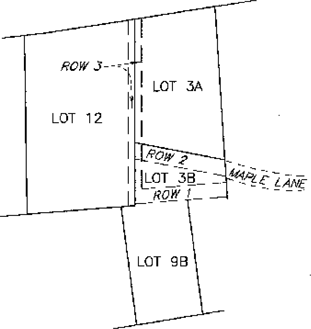

1. Background. The locus, known as 12 Maple Lane, is comprised of two adjacent lots, formerly known as lot 2 and lot 3A, totaling 18,086 square feet. [Note 2] A ten-foot right of way, referred to as "ROW 3," runs in a northerly direction along the borders of lots 2 and 3A, comprised of five feet from each lot. [Note 3]

Perry's property, known as 9B Maple Way, lies south of lot 3A. He has two lots, lots 9B and 3B. On the northern boundary of Perry's lot 3B, running in an east to west direction along the angled boundary, lies a private way known as "ROW 2." ROW 2 intersects ROW 3 and is shown as terminating in the middle of ROW 3. The locus and other surrounding properties and rights in the private ways providing access to them were the subject of our prior opinion, Perry v. Nemira, 91 Mass. App. Ct. 12 (2017) (Perry I). Although that case definitively determined the parties' rights (or their predecessors' rights, which have passed to the parties) over certain private ways, including access to the locus over ROW 2, Perry now asserts that the locus's frontage on ROW 2 does not satisfy the seventy-five foot requirement of the bylaw because Perry I and the subsequent decision of the Land Court on remand establish that ROW 2 along lot 3A is sixty-nine feet.

The locus abuts both the northern sideline of ROW 2 and the western end of ROW 2. To satisfy the seventy-five foot frontage requirement of the SF-B district where the properties are located, the owners rely not only on the sixty-nine feet that abut the northern sideline of ROW 2, but also upon the twelve feet that

Page 21

abut the end of ROW 2. As such, the frontage that the owners rely upon takes a sharp turn.

The bylaw defines "Lot Frontage" as "[t]hat part of a lot (a lot line) abutting on a street or way; except that the ends of incomplete streets, or streets without a turning circle, shall not be considered frontage . . . ." The exception following the semicolon has been referred to as the "incomplete street exception," or the "incomplete streets exception." Under the bylaw, frontage is measured in linear feet.

After the town's building commissioner granted a building permit to the owners, Perry appealed to the board, asserting (among other things), that the locus lacked the frontage required by the bylaw. The board upheld the building permit, and Perry appealed to the Land Court under G. L. c. 40A, § 17.

The parties submitted cross motions for summary judgment. In deciding those motions, the judge rejected Perry's claims that the locus is not a "Lot" as defined in the bylaw and that the proposed house would violate a side setback requirement. The judge, however, remanded to the board the issue whether the "incomplete streets exception" applies such that the portion of the locus that abuts the end of ROW 2 does not qualify as frontage. On remand, the board decided that the incomplete street exception does not apply. On Perry's second motion for summary judgment, the Land Court judge agreed with the board and affirmed the grant of the building permit. Perry now appeals and raises issues decided in both summary judgment decisions.

2. Standard of review. "We review the judge's determinations of law, including interpretations of zoning bylaws, de novo." Fish v. Accidental Auto Body, Inc., 95 Mass. App. Ct. 355, 362 (2019), quoting Shirley Wayside Ltd. Partnership v. Board of Appeals of Shirley, 461 Mass. 469, 475 (2012). "We accord deference to a local board's reasonable interpretation of its own zoning bylaw . . . with the caveat that an 'incorrect interpretation of a statute . . . is not entitled to deference.'" Doherty v. Planning Bd. of Scituate, 467 Mass. 560, 566 (2014), quoting Shirley Wayside Ltd. Partnership, supra. "Where the board's interpretation is reasonable . . . , the court should not substitute its own judgment." Tanner v. Board of Appeals of Boxford, 61 Mass. App. Ct. 647, 649 (2004).

3. Frontage. a. Incomplete streets exception. Perry asserts that the definition of frontage, together with the requirement that frontage be measured in linear feet, precludes the owners from relying

Page 22

on the end of ROW 2 for frontage. In finding that the end of ROW 2 may be counted as frontage, both the board and the judge distinguished between "private ways" and "streets" in interpreting the incomplete street exception. Although Perry agrees that ROW 2 is a private way and not a "street," [Note 4] he asserts on appeal that the bylaw uses "street" and "way" interchangeably and that, by providing that the end of a street may not be considered frontage, the town meeting in drafting the bylaw also intended to provide that the ends of private ways may not be considered frontage.

Perry's interpretation is not without basis. Indeed, as the judge noted, there may be times when the bylaw appears to use the terms "street" and "way" interchangeably. [Note 5] In defining "Frontage," however, the bylaw first includes any lot line abutting a "street or way." When the bylaw subsequently creates the "incomplete streets exception" after the semicolon, it refers conspicuously only to streets and does not include ways. [Note 6] Regardless of whether the bylaw uses the terms interchangeably elsewhere, it was not unreasonable for the board to conclude that in this instance, the reference to only streets was intentional where both street and way had been used earlier in the same sentence. "It is a 'maxim of statutory construction . . . that a statutory expression of one thing is an implied exclusion of other things omitted from the statute.'" Metropolitan Prop. & Cas. Ins. Co. v. Emerson Hosp., 99 Mass. App. Ct. 513, 522 (2021), quoting Harborview Residents' Comm., Inc. v. Quincy Hous. Auth., 368 Mass. 425, 432 (1975). Although this maxim, commonly known as "expressio unius est exclusio alterius," must be applied with caution, see Phillips v. Equity Residential Mgt., L.L.C., 478 Mass. 251, 259 n.19 (2017); Perry I, 91 Mass. App. Ct. at 19, it has particular force where the

Page 23

excluded phrase was used elsewhere in the same provision. See Commonwealth v. Muckle, 478 Mass. 1001, 1002-1003 (2017). See also Malloy v. Department of Correction, 487 Mass. 482, 497 (2021), quoting Souza v. Registrar of Motor Vehicles, 462 Mass. 227, 232 (2012) ("[W]here the Legislature has employed specific language in one paragraph, but not in another, the language should not be implied where it is not present").

It is not our role to evaluate the wisdom of a zoning ordinance. See DiRico v. Kingston, 458 Mass. 83, 95 (2010), quoting Durand v. IDC Bellingham, LLC, 440 Mass. 45, 51 (2003) ("If the reasonableness of a zoning bylaw is even 'fairly debatable, the judgment of the local legislative body responsible for the enactment must be sustained'"). Although we would not give deference to an unreasonable interpretation of the bylaw, it is not unreasonable to treat the obvious safety concerns of an incomplete public way, or one terminating without a turnaround, differently from private ways that are incomplete or lack turnarounds. At oral argument, counsel for the owners pointed out that here, their driveway, which will be located off ROW 2 before the intersection with ROW 3, will allow them and their guests to change direction with relative ease. The fact that the general public will not have access to ROW 2 (a private way) is significant.

Even if Perry's interpretation of the bylaw and the board's interpretation of the bylaw were both reasonable, we must defer to the board's reasonable interpretation. See Tanner, 61 Mass. App. Ct. at 649. Accordingly, the judge properly applied the board's reasonable interpretation of the town's bylaw.

b. Measuring frontage. Perry also argues that, because a minimum of seventy-five feet of "frontage in linear feet" is required, the locus does not qualify because its frontage is not in a straight line. Putting aside the fact that Perry did not raise this issue before the Land Court, the bylaw does not require frontage to be straight. Rather, it requires that frontage be measured in linear feet. Measuring something in "linear feet" merely means that the size of something is measured without reference to its other dimensions, such as width or height. See, e.g., Sears v. United States, 132 Fed. Cl. 6, 24 (2017); Crowley v. Police Jury of Acadia Parish, 138 La. 488, 499 (1915). This can provide clarity when measuring or pricing something for which the width or height would ordinarily be important, but are not to be part of the calculation. See, e.g., Boston Gas Co. v. Newton, 425 Mass. 697, 701 n.9 (1997) (piping measured in linear feet); Chase Precast Corp. v. John J. Paonessa

Page 24

Co., 409 Mass. 371, 372 (1991) (contract to provide concrete median barriers measured in linear feet); Cave Corp. v. Conservation Comm'n of Attleboro, 91 Mass. App. Ct. 767, 769 (2017) (proposed roadway measured in linear feet); Sciaba Constr. Corp. v. Boston, 35 Mass. App. Ct. 181, 183-184 (1993) (bid to paint roadway striping calculated at $15 per linear foot). Accord McKinney Drilling Co. v. Collins Co., 517 F. Supp. 320, 326 (N.D. Ala. 1981), aff'd, 701 F.2d 132 (11th Cir. 1983) (caisson work customarily priced "based on the linear feet of earth and rock to be excavated"). And, though a linear foot measurement is a "straight" foot, the item being measured need not be straight. For example, the perimeter of an acre that consists of a perfect square is approximately 835 linear feet. But the perimeter of an acre that is circular can also be measured; in that case, the number of linear feet equals the circumference of the plot, approximately 740 linear feet. Thus, that frontage is measured in linear feet, without more, does not require frontage to be in a straight line.

4. Satisfaction of lot requirements. Perry also argues that the locus does not comply with the bylaw's definition of a "Lot." The bylaw defines a lot as "[a] contiguous parcel of land in identical ownership throughout, bounded by other lots or by streets, and used or set aside and available for use as the site of one principal building with one or more accessory buildings. For the purpose of this bylaw, a lot may or may not coincide with a lot on record." First, Perry argues that, to be a lot, the locus must abut a street. The definition, however, provides that a lot may be bounded by other lots. Here, the locus is bounded on all sides by other lots. Indeed, ROW 2, which provides the frontage for the locus, as established in Perry I, is itself located on the northern portion of Perry's lot. Thus, the locus is bounded on all sides by lots and meets the definition of "Lot" contained in the bylaw.

Next, Perry argues that the locus cannot be considered a single lot both because it is comprised of what once were two adjacent lots, and because ROW 3, the easement that runs along the borders of the two lots, prevents the locus from being treated as a single lot. The definition of "Lot," contained in the bylaw, however, does not require that there be no easements on the property.

The fact that the bylaw generally excludes the square footage contained in a public or private street or way from the calculation of lot area is of no matter. Even assuming that ROW 3, which apparently is not laid out on the ground, qualifies as a private way, nothing in the definition of "Lot" prohibits a lot from being

Page 25

bisected by a private way, so long as the entirety of the lot (including the private way) has identical ownership. At most, the square footage of that private way would be excluded from the square footage in calculating the lot size. [Note 7] We conclude, therefore, that there was no error in treating the locus as a single lot. [Note 8]

5. Miscellaneous arguments. Perry argues that ROW 2 must be constructed in accordance with the standards in the Subdivision Control Law, G. L. c. 41, §§ 81K-81GG. [Note 9] Perry points to nothing in the bylaw, however, that requires compliance with c. 41 before the building commissioner may issue a building permit, and the judge found that the bylaw does not require such compliance. Similarly, Perry points to nothing in the bylaw that requires ROW 2 to be a public way or a "statutory" private way.

Finally, Perry argues that the board acted with gross negligence, bad faith, and malice. Although Perry's assertions, if true, would be concerning, he failed to provide a record to support the factual assertions that form the basis of his claims. See Davis v. Tabachnick, 425 Mass. 1010, 1010, cert. denied, 522 U.S. 982 (1997). That Perry proceeded pro se does not relieve him of the obligation to present an adequate record to allow proper review of his claims. See id. [Note 10]

Judgment affirmed.

Page 26

Appendix

FOOTNOTES

[Note 1] Building commissioner of Hull, Charles Williams, and Ann Williams. Although the complaint names "Ann Williams," the parties and the Land Court refer to her as "Anne Veilleux" throughout, as shall we.

[Note 2] The more recent plan in the record on appeal refers to lot 2 as lot 12. This parcel of land was designated as lot 2 in a plan dated August 1911, and we refer to it as such to be consistent with Perry v. Nemira, 91 Mass. App. Ct. 12 (2017). A sketch based on the more recent plan is attached to this opinion as an appendix. "[W]e have commissioned the sketch from the [survey division] of the Land Court as an aid to our decision. The sketch is included only for purposes of analysis and is not intended to be complete and accurate for any other purpose." Burwick v. Massachusetts Highway Dep't, 57 Mass. App. Ct. 302, 303 n.4 (2003).

[Note 3] A home previously existed on what was lot 2. That home has been razed and only the foundation remains. The owners propose to construct a home on the eastern half of the property, on what was once lot 3A.

[Note 4] The judge found that ROW 2 is a private way. The judge noted in his first decision that the bylaw does not define "street" or "way," but, prior to remanding for further consideration by the board, the judge held that "'street' could mean either 'a public way or thoroughfare in a city or town,' or . . . 'a roadway for vehicles apart from . . . buildings and sidewalks.'" Following remand, the judge found that the board had adopted the first definition, which distinguishes a "street" from a "way" on the basis that a street is a public way. On appeal to this court, Perry does not quibble with the judge's finding that the board adopted a definition of "street" that means it is a public way.

[Note 5] The bylaw uses "street" in the definition of "Lot Line, Rear" where it may refer to either a street or way. By contrast, in the definitions of "Lot Area," "Lot Line, Front," and "Street Line," the bylaw uses both street and way, suggesting that town meeting considered them to be different.

[Note 6] So far as the record reveals, the bylaw does not specifically address corner lots with respect to frontage.

[Note 7] It is uncontested here that the locus is of sufficient size regardless of whether the square footage of ROW 3 is excluded from the calculation. Contrary to Perry's suggestion, the bylaw does not require that the lot be shown on a recorded plan.

[Note 8] Perry also argues that the proposed house must be set back twenty-five feet from ROW 3 if the end of ROW 2, coinciding with ROW 3, is considered frontage. Perry points to nothing in the bylaw requiring ROW 3 to be considered in determining front setback. The proposed frontage is entirely on ROW 2. Moreover, "Yard" is defined in the bylaw as "[t]he open space at the front, sides and rear of a building between the exterior walls of the building and the boundaries of the lot upon which it stands." Although ROW 2 is a boundary of the locus, the northern portion of ROW 3 is not.

[Note 9] The subdivision here was completed well before the passage of the Subdivision Control Law. See St. 1947, c. 340, § 4. Accord G. L. c. 41, § 81FF.

[Note 10] The board and building inspector's request for appellate attorney's fees and costs is denied. "Although the . . . appeal is unsuccessful, it is not frivolous." Filbey v. Carr, 98 Mass. App. Ct. 455, 462 n.10 (2020), quoting Gianareles v. Zegarowski, 467 Mass. 1012, 1015 n.4 (2014).