MARGOT XARRAS, TRUSTEE OF HIGHLAND MANOR REALTY TRUST and JAMES L. XARRAS, TRUSTEE OF UNION SQUARE REALTY TRUST v. JAMES S. WHITNEY, TRUSTEE OF 557 LANCASTER STREET REALTY TRUST

MARGOT XARRAS, TRUSTEE OF HIGHLAND MANOR REALTY TRUST and JAMES L. XARRAS, TRUSTEE OF UNION SQUARE REALTY TRUST v. JAMES S. WHITNEY, TRUSTEE OF 557 LANCASTER STREET REALTY TRUST

MISC 08-387228

November 16, 2011

Sands, J.

DECISION

Plaintiffs Highland Manor Realty Trust (Highland Manor) and Union Square Realty Trust (Union Square) (together, Plaintiffs) filed their unverified Complaint on November 7, 2008, seeking (1) declaratory judgment relative to rights in an easement across property owned by 557 Lancaster Street Realty Trust (Defendant), (2) removal of granite curbing by Defendant in the easement area, and (3) alleging trespass by Defendant across Plaintiffs properties in the installation of electrical service cables. Plaintiffs filed a Motion for Temporary Restraining Order on February 4, 2009, which was subsequently withdrawn. [Note 1] A case management conference was held on February 10, 2009. [Note 2] Defendant filed its Motion for Summary Judgment on October 25, 2010, together with supporting memorandum, Statement of Material Facts, exhibits, Affidavits of Larry R. Sabean (Land Surveyor) and James M. Donovan (Attorney), and an Affidavit of James S. Whitney (Whitney Affidavit 2). On November 24, 2010, Plaintiffs filed their Opposition and Cross-Motion for Summary Judgment, together with supporting memorandum, Statement of Material Facts, and Affidavits of James L. Xarras (Xarras Affidavit 2), Joseph M. Gibbons (Truck Driver), Pelino Camapagna (Delivery Driver), and Leonard Mallard (husband of employee working on the Union Square Property, as hereinafter defined) (the Mallard Affidavit). Defendant filed its Opposition to Plaintiffs Cross-Motion on December 6, 2010, together with a Second Affidavit of James S. Whitney. [Note 3] A hearing was held on both motions on January 19, 2011, and the matter was taken under advisement.

Summary judgment is appropriate where there are no genuine issues of material fact and where the summary judgment record entitles the moving party to judgment as a matter of law. See Ng Bros. Constr. v. Cranney, 436 Mass. 638 , 643-44 (2002); Cassesso v. Commr of Corr., 390 Mass. 419 , 422 (1983); Mass. R. Civ. P. 56(c).

I find the following material facts are not in dispute:

1. Leominster Manufacturers Trust, Inc. owned a large parcel of land in Leominster, Massachusetts, as shown on a plan titled Land in Leominster, Mass. Owned by Leominster Manufacturers Trust, Inc. dated July 3, 1946, and recorded with the Worcester Northern District Registry of Deeds (the Registry) at Plan Book 77, Page 9, and prepared by William P. Ray (the 1946 Plan). [Note 4] By deeds dated December 10, 1946 (the 1946 Deeds) and recorded with the Registry at Book 625, Page 303, Leominster Manufacturers Trust, Inc. conveyed easement rights to several grantees, including the predecessors in title to the parties to this action, all of the 1946 Deeds having language as follows:

the following perpetual rights and easements to be exercised in common with all others to whom the Grantor has or may grant the same or similar rights:

1. To use for the purposes of travel, all roadways upon premises owned by the Grantor under deed of E. I. Du Pont de Nemours and Company to Grantor recorded Worcester Northern District Registry of Deeds, Book 614, Page 428 which roadways are to be ascertained by reference to that part showing roads of a certain plan in five sheets prepared for Grantor by William P. Ray, C.E. dated July 3, 1946. [Note 5]

2. By deed dated October 10, 2003, and recorded with the Registry at Book 5002, Page 284, (the Menchi Deed) Clevio U. Menchi conveyed a small portion of property labeled as the Plastic Turning Co. Inc. on the 1946 Plan to Defendant (Defendant Property). The 1946 Plan shows the property labeled Plastic Turning Co. Inc. as a roughly triangular parcel in the easterly (lower left-hand) corner fronting on both Lancaster Street and Malburn Street and containing eight acres 42,340 square feet, with greater detail shown on pages 1 (77.9B), 2, and 3 (77.9D). The area comprising Defendant Property is shown in greater detail on Page 1 (77.9B) of the 1946 Plan. The boundaries of Defendant Property are shown on Building Plot Plan in Leominster, Massachusetts dated February 25, 2004, and recorded with the Registry at Book 5002, Page 284 (the 2004 Plan). [Note 6] Defendant Property contains 26,100 square feet, according to the 2004 Plan. Defendant Property fronts on Lancaster Street, but does not extend as far south as Malburn Street, its southerly boundary being the thread of Fall Brook.

3. By deed dated March 23, 2004, and recorded with the Registry at Book 5187, Page 177, Superior Comb Company, Inc. conveyed property labeled as Pyrotex Leather Company on the 1946 Plan, containing one acre 2814 square feet (the Highland Manor Property) to Highland Manor. It is improved with one building.

4. By deed dated July 6, 2007 (the Banknorth Deed), and recorded with the Registry at Book 6534, Page 239, TD Banknorth, N.A. conveyed 8.06 acres of land to Union Square (the Union Square Property). The Union Square Property includes the majority of the property labeled as the Plastic Turning Co. Inc. on the 1946 Plan. [Note 7] According to the Banknorth Deed, the Union Square Property is shown on a plan titled Compiled Plan, Land in Leominster, Mass. Owned by George K. Progin et als, Trustees, dated January 11, 1980, recorded with the Registry at Plan Book 239, Page 19, and prepared by William R. Bingham (the 1980 Plan). [Note 8] The Union Square Property abuts Defendant Property on the north and is improved with several buildings.

5. Included in the easement rights conveyed in the 1946 Deeds, and labeled Gravel Road on the 1946 Plan, was a gravel road (the Gravel Road) crossing what is now Defendant Property and connecting Lancaster Street with what is now the Union Square Property and a network of roads serving the Highland Manor Property. As shown on the 1946 Plan, the Gravel Road ran westerly from Lancaster Street along the north side of a single building (the Former Building) on Defendant Property, which building was divided into parts labeled 1A and 1B. [Note 9]

6. Defendant Property is shown on the 2004 Plan, labeled as MAP 443A LOT 3 (26,100 ± SF). As shown on the 2004 Plan, the Former Building no longer exists, but today would be on Defendant Property. [Note 10] At issue in this case is the right-of-way across Defendant Property corresponding to the Gravel Road (the Deeded Easement).

7. Since the early 1970s, no part of the Gravel Road has existed on Defendant Property.

8. Defendant Property contains approximately 26,100 square feet and has frontage on Lancaster Street (Route 117) in Leominster, Massachusetts.

9. Defendant Property is currently improved with one one-story concrete block building (the Present Building), which contains approximately 12,000 square feet of rentable space; on the 2004 Plan it is labeled EXISTING 1 STOREY BLOCK BUILDING. The Present Building is situated on the site of the Former Building, but is larger. [Note 11] The Present Building occupies all of the space occupied by the Former Building, as well as extending north and south. [Note 12] The Present Building has not changed in size or location for at least forty years. [Note 13]

10. The 1946 Plan shows the Deeded Easement running alongside the Former Building. The Deeded Easement would run through the Present Building as shown on the 2004 Plan.

11. Since the early 1970s, Defendant has had exclusive use of the portion of the Gravel Road now within the bounds of the Present Building.

12. Certain other roads connected to the Deeded Easement and shown on the 1946 Plan are also blocked by buildings, including roads on the Union Square Property.

13. Easement rights over Defendant Property were disputed in an action brought in the Land Court by Union Squares predecessor, Union Products Realty Corporation (UPRC) [Note 14] (04 MISC 303265) (the Prior Action). [Note 15] UPRC and Defendant executed an Agreement for Judgment (the Agreement for Judgment) dated June 20, 2005, giving UPRC an easement over Defendant Property in a location other than the Gravel Road (the Agreed Easement). [Note 16] The Agreement for Judgment stated that plaintiff releases any right of claim to area outside of created way . . and that [t]his Agreement for Judgment takes effect as a judgement on the merits, with prejudice, waiving rights of appeal and costs.

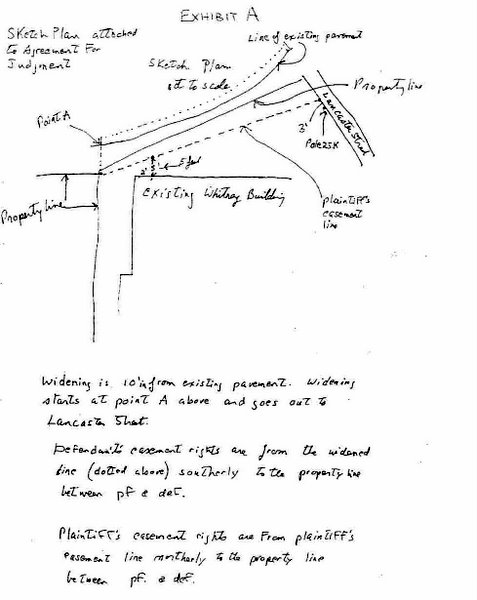

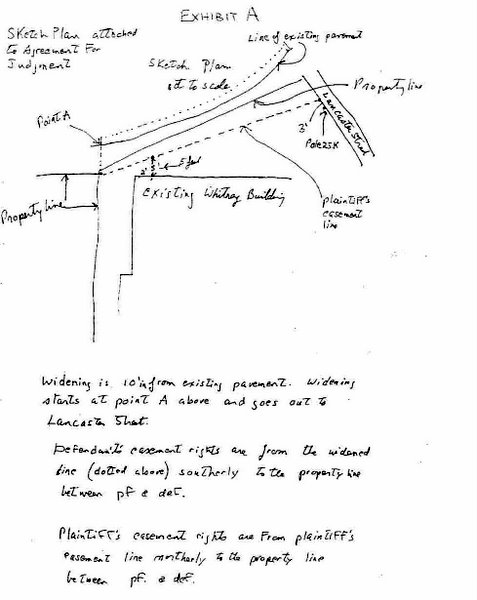

14. The Agreed Easement is described in a sketch plan attached to the Agreement for Judgment (the Sketch Plan), and recorded with the Registry at Book 6827, Page 114. The width of the Agreed Easement is not specified. The Agreed Easement does not appear on any plan in the summary judgment record other than the Sketch Plan.

15. As described in the Agreement for Judgment and as shown on the Sketch Plan, the Agreed Easement runs southwesterly from Lancaster Street, overlapping both sides of the property line between Defendant Property and the Union Square Property. The Agreed Easement runs to the north of the Present Building and is closest to the Present Building at the Present Buildings northwest corner. The southerly boundary of the Agreed Easement is an apparently straight line running from the northwesterly corner of Defendant Property to Lancaster Street, passing through a point five feet northerly from a point on the north side of the Present Building that is two feet easterly from the Present Buildings northwest corner. [Note 17] The northerly boundary of the Agreed Easement is defined relative to the width of pavement existing at the time of the Agreement for Judgment. The Sketch Plan states:

Widening is 10' in from existing pavement. [Note 18] Widening starts at point A [Note 19] above and goes out to Lancaster Street.

Defendants easement rights are from the widened line (dotted above) southerly to the property line between [plaintiff and defendant].

Plaintiffs easement rights are from Plaintiffs easement line northerly to the property line between [plaintiff and defendant].

16. A number of employees and invitees of Union Square represented that the Union Square Property has been accessed for at least twenty years by means of a way approximately twenty feet wide running along the north side of the Present Building (the Adjacent Way). [Note 20]

The Gibbons Affidavit, dated November 19, 2010, states that the affiant made deliveries to the Union Square Property from 1970 to 1972 and on a regular basis for the last 20+ years (i.e., 1990-2010). The Camapagna Affidavit, dated November 18, 2010, states that the affiant has made deliveries to the Union Square Property for the last 35 years (i.e., 1975-2010). The Gibbons and Camapagna Affidavits both state that the affiants would always and consistently access the Union Square Property by virtue of driving along the paved roadway, which is approximately twenty feet wide, that runs along the side of the [Present Building]. The Mallard Affidavit, dated November 18, 2010, states that the affiant is familiar with Defendant Property as a result of his wifes employment from 1980 to 2005 on the Union Square Property. The Mallard Affidavit states that the affiant picked up his wife on a regular basis for the last 30 years on the Union Square Property, and would always and consistently access [the Union Square Property] and observe the paved roadway, which is approximately twenty feet wide, that runs along the side of the [Present Building]. [Note 21]

The Adjacent Way is not shown on any plan in the summary judgment record. Xarras Affidavit 2, dated November 24, 2010, states that regular deliveries are made by trucks to the Union Square Property, and that [f]or at least twenty years, the trucks accessed the buildings behind the Defendants [sic] property by virtue of the area shown as the Relocated Easement Area on the sketch attached hereto as Exhibit A [the Adjacent Way].

17. Attached to Xarras Affidavit 2 as Exhibit A is a copy of the 2004 Plan with the location of the Adjacent Way drawn in by hand and labeled Relocated Easement Area (Xarras Exhibit A). As shown on Xarras Exhibit A, the Adjacent Way runs parallel to the north side of the Present Building and connects Lancaster Street to the Union Square Property. As shown on Xarras Exhibit A, the Adjacent Ways southerly boundary appears to be perpendicular to Defendant Propertys westerly boundary and appears not to touch the Present Building, but to be a short distance north of it. [Note 22]

18. The area along the northerly side of the Present Building is used for parking in defined spaces and related activities in connection with Defendant Property. [Note 23]

19. There is granite curbing on the northerly side of Defendant Property. [Note 24]

*******************************

Plaintiffs claim a right-of-way (the Deeded Easement) over Defendant Property pursuant to the 1946 Deeds. In the alternative, Plaintiffs claim that the Deeded Easement was relocated to another location (the Adjacent Way) or that they have acquired a prescriptive easement in the Adjacent Way. To the extent that Plaintiffs argue that the Deeded Easement was relocated to the Adjacent Way or that they have acquired a prescriptive easement in the Adjacent Way, Plaintiffs allege that Defendant has obstructed access to Plaintiffs properties, especially by trucks, by installing granite curbing along the boundary between Defendant Property and Lancaster Street, and by providing striped parking spaces adjacent to and northerly of the Present Building. [Note 25] In addition, Plaintiffs claim that Defendant has trespassed in the installation of electrical service cables on the Union Square Property.

Defendant contends that Union Squares claim to the Deeded Easement is barred by principles of res judicata, due to an earlier action that relocated the Deeded Easement to the Agreed Easement. Therefore, Defendant argues that the Agreed Easement is the only valid right-of-way that Union Square has over Defendant Property to reach the Union Square Property. Defendant further argues that any rights-of-way created by the 1946 Deeds were extinguished by abandonment because buildings today exist in the location of the Deeded Easement shown on the 1946 Plan. In the alternative, Defendant argues that it has extinguished the Deeded Easement by adverse possession. Defendant also maintains that the Deeded Easement was not relocated apart from any relocation to the Agreed Easement that may have resulted from the Agreement for Judgment. Therefore, Defendant asserts that any obstruction to any valid right-of-way that Plaintiffs have over Defendant Property resulted from Plaintiffs own actions, including placing trucks and heavy equipment on the Agreed Easement. Finally, Defendant denies that it has trespassed in the installation of electrical service cables on the Union Square Property. I shall look at each of these issues in turn.

Res Judicata.

As an initial matter, Defendant asserts that Union Squares claim to the Deeded Easement is precluded by an action brought in the Land Court (04 MISC 303265) by Union Squares predecessor (the Prior Action). [Note 26] The Prior Action was resolved in the Agreement for Judgment. [Note 27] The Sketch Plan clearly marks the boundaries of the Agreed Easement as defined by the Agreement for Judgment and clarifies its language. [Note 28] The Agreed Easement is not the Deeded Easement or the Adjacent Way. The Agreed Easement runs southwesterly from Lancaster Street along the entire northern boundary of Defendant Property. The Agreed Easement runs north of the Present Building and is closest to the Present Building at its northwest corner. [Note 29]

Res judicata is a generic term encompassing both claim and issue preclusion. Baby Furniture Warehouse Store, Inc. v. Meubles D&F Ltée, 75 Mass. App. Ct. 27 , 33 (2009). Claim Preclusion makes a valid, final judgment conclusive on the parties and their privies, and prevents relitigation of all matters that were or could have been adjudicated in the action. Aspinall v. Philip Morris Companies, Inc., 442 Mass. 381 , 397 n.19 (2004). The doctrine is grounded on considerations of fairness and judicial efficiency. Id. The invocation of claim preclusion requires three elements: (1) the identity or privity of the parties to the present and prior actions, (2) identity of the cause of action, and (3) prior final judgment on the merits. Kobrin v. Bd. of Registration in Medicine, 444 Mass. 837 , 843 (2005) (quoting DaLuz v. Dept of Correction, 434 Mass. 40 , 45 (2001)). Issue preclusion also has three elements. A court must determine that (1) there was a final judgment on the merits in the prior adjudication; (2) the party against whom preclusion is asserted was a party (or in privity with a party) to the prior adjudication; and (3) the issue in the prior adjudication was identical to the issue in the current adjudication. Id. (quoting Tuper v. North Adams Ambulance Serv., Inc., 428 Mass. 132 , 134 (1998)). Additionally, the issue decided in the prior adjudication must have been essential to the earlier judgment. Tuper, 428 Mass. 132 at 134-35.

The elements of both claim preclusion and issue preclusion are present in this case. First, UPRC is Union Squares predecessor in title and therefore they are in privity. See Brooks v. Secretary of the Commonwealth, 257 Mass. 91 , 94 (1926) (citing Litchfield v. Goodnows Administrator, 123 U.S. 549, 551 (1887) ([T]he term 'privity' denotes mutual or successive relationship to the same rights of property.)). [Note 30]

Second, with regard to claim preclusion, the underlying cause of action is the same in both cases. In the Prior Action, UPRC claimed an easement by prescription, asserting that it and its predecessors had uninterrupted use . . . for all purposes for which a driveway is commonly used, including but not limited to access to the UPRC Property by delivery trucks, openly, notoriously and adversely for a period of more than twenty (20) years. In the case at bar, Union Square also argues that it is entitled to an easement by prescription. It is true that in the case at bar the prescriptive easement is argued in the alternative to two arguments that the record does not show were made in the Prior Action: an argument that the easement was relocated to the Adjacent Way and an argument for enforcement of the Deeded Easement, including a request that Defendant be ordered to remove buildings blocking it. However, claim preclusion applies even though the claimant is prepared in a second action to present different evidence or legal theories to support his claim, or seeks different remedies. Heacock v. Heacock, 402 Mass. 21 , 23 (1988). [T]here is nothing in the complaint in the present case that was not, or could not have been, brought in the first complaint. Tynan v. Attorney Gen., 453 Mass. 1005 , 1005 (2009). Even if the two claims were construed to not be identical, the basic issue in each case is the same for purposes of issue preclusion: whether Plaintiffs have an access easement to and from Lancaster Street and where such easement is.

Third, a prior final judgment on the merits, or its equivalent for res judicata purposes, was issued in the Prior Action. A consent judgment . . . conclusively determines the rights of the parties as to all matters within its scope. Kelton Corp. v. County of Worcester, 426 Mass. 355 , 359 (1997). [Note 31] Furthermore, the Agreement for Judgment explicitly states that it takes effect as a judgement on the merits. [Note 32] See Turner v. Community Homeowners Assn, Inc., 62 Mass. App. Ct. 319 , 327 (2004) (following the rule in Restatement (Second) of Judgments that a consented to judgment may be conclusive . . . with respect to one or more issues, if the parties have entered an agreement manifesting such an intention).

On the basis of the foregoing, I find that Union Squares claim to the Deeded Easement is barred by the doctrine of res judicata. I further find that Union Square continues to have the benefit of the Agreed Easement. [Note 33]

As discussed, infra, the doctrine of res judicata also bars Union Squares claim to the Adjacent Way, inasmuch as the Agreement for Judgment implicitly indicates that Union Square had no intent to relocate the Deeded Easement to the Adjacent Way, and inasmuch as the Agreement for Judgment released any right to a prescriptive easement benefitting Union Square that it may have acquired prior to the Agreement for Judgment.

Abandonment.

Plaintiffs argue that neither they nor their predecessors abandoned the Deeded Easement, because they have shown no intention to abandon the Deeded Easement. Moreover, they argue that their use of the Adjacent Way indicates their intention not to abandon the Deeded Easement. Since the Adjacent Way could be a second best right-of-way after the Deeded Easement was blocked, Plaintiffs argue that their use of the Adjacent Way shows that they never relinquished their rights in the Deeded Easement, but instead continued to assert those rights by using a very close substitute.

Defendant contends that Plaintiffs or their predecessors clearly abandoned the Deeded Easement, because the roads shown on the 1946 Plan have not provided access for more than forty years. Defendant asserts on the basis of Whitney Affidavit 2 and Plaintiffs concede that the concrete building now blocking the original Deeded Easement has not changed in size or shape since the early 1970s. Defendant argues that a concrete building placed on top of an access way strongly indicates that the Deeded Easement was abandoned. [Note 34]

It is well settled that an easement may be lost by abandonment, but abandonment is a question of intention. Parlante v. Brooks, 363 Mass. 879 , 880 (1973). There must be acts by the owner of the dominant estate of such conclusive and unequivocal character as manifest a present intent to relinquish the easement or such as are incompatible with its further existence. Willets v. Langhaar, 212 Mass. 573 , 575 (1912). [M]ere nonuse is insufficient to demonstrate an intent by the dominant estate holder to abandon the easement. Patterson v. Paul, 448 Mass. 658 , 668 (2007).

The Agreement for Judgment, discussed supra, plainly indicates Union Squares intent to abandon the Deeded Easement by its statement that [P]laintiff releases any right of claim to area outside of created right of way. As such, the Agreement for Judgment supersedes the Deeded Easement and Union Squares approval of the Agreement for Judgment is incompatible with the Deeded Easements further existence with respect to Union Square.

Plaintiffs argument implies that the act of abandonment was carried out by the owner of the servient estate when the Present Building or an addition to the Former Building was constructed. However, the physical prominence of the Present Building and the possible intent of the owner of the servient estate distract from the important issue: Plaintiffs or their predecessors intent. Even though Plaintiffs did not construct the building on the Deeded Easement, its presence still shows their intent. [C]ases indicate that failure to protest acts which are inconsistent with the existence of an easement, particularly where one has knowledge of the right to use the easement, permits an inference of abandonment. The 107 Manor Avenue LLC v. Fontanella, 74 Mass. App. Ct. 155 , 158 (2009). A concrete building is such a blatant impediment to an access way that Plaintiffs or their predecessors would not have allowed the construction if they had not had the intention to abandon the Deeded Easement. Cf. Sindler v. William M. Bailey Co., 348 Mass. 589 , 593 (1965) (finding that the respondent [had] permitted the occurrence of events and relatively permanent changes in the disputed area, all of which combine to warrant an inference that it [had] abandoned its rights to the easement in question). [Note 35]

Furthermore, Plaintiffs argument with regard to alternative access poses logical problems. Union Squares use of the Adjacent Way shows its intent to access the Union Square Property by way of a different easement area than the Deeded Easement on Defendant Property and may show an intent to relocate the Deeded Easement, as discussed, infra, but it does not show an intent to maintain the Deeded Easement as such. To the extent that Plaintiffs argue that Highland Manor has used the Adjacent Way to access the Highland Manor Property, such access also does not show Highland Manors intent to maintain the Deeded Easement as such. Plaintiffs cannot have it both ways; if they truly had an intent not to abandon the Deeded Easement, at some point they compromised such intent by resorting to the Adjacent Way.

Based on the foregoing, I find that the Deeded Easement was abandoned by Plaintiffs, inasmuch as Plaintiffs showed intent to abandon by allowing Defendant to construct or enlarge a building to block the Deeded Easement and inasmuch as Union Square released its right to the Deeded Easement in the Agreement for Judgment in the Prior Action.

Relocation to the Adjacent Way.

In the alternative, Plaintiffs assert that the Deeded Easement was relocated when Defendants predecessor constructed or enlarged the building that now blocks the Deeded Easement. Specifically, Plaintiffs argue that the Deeded Easement was relocated to the Adjacent Way. Plaintiffs maintain that the actions of the parties and their predecessors show a mutual intent to relocate the Deeded Easement. [Note 36] In particular, they assert that the Adjacent Way has been used by trucks to make regular deliveries for at least twenty years. Plaintiffs produce Xarras Affidavit 2, dated November 22, 2010, which states:

4. The buildings on [the Union Square Property] exceed 100,000 square feet of warehouse space with approximately twenty loading docks.

5. Regular deliveries are made by trucks on a daily basis.

6. For at least twenty years, the trucks accessed the buildings behind the Defendants [sic] property by virtue of [the Adjacent Way].

Plaintiffs also produce affidavits from two truck drivers, Joseph Gibbons and Pelino Camapagna. The Gibbons Affidavit, dated November 19, 2010, states:

4. I made deliveries from 1970 to 1972 and on a regular basis for the last 20+ years to Union Products[,] which is located behind the [Present Building].

5. I would always and consistently access the Union Products building [Note 37] by virtue of driving along the paved roadway, which is approximately twenty feet wide, that runs along the side of the [Present Building].

The Camapagna Affidavit, dated November 18, 2010, states:

4. I made deliveries on a regular basis for the last 35 years to Union Products[,] which is located behind the [Present Building]. And I currently deliver to Lasership located at 523 Lancaster Street [Note 38] . . .

5. I would always and consistently access the Union Products building by virtue of driving along the paved roadway, which is approximately twenty feet wide, that runs along the side of the [Present Building]. I currently use the same access for my deliveries to Lasership.

In addition, Plaintiffs produce the Mallard Affidavit, dated November 18, 2010, which states:

2. From 1980 to 2005, . . . my wife . . . worked at Union Products at 511 Lancaster Street, Leominster . . .

3. As a result of my wifes employment, I am familiar with [Defendant Property] which was formerly known as Laurier Press.

4. I picked up my wife on a regular basis for the last 30 years at Union Products which is located behind the former Laurier Press building.

5. I would always and consistently access the Union Products building and observe the paved roadway, which is approximately twenty feet wide, that runs along the side of the former Laurier Press building. [Note 39]

The access to the Union Square Property described in Xarras Affidavit 2 is defined in Xarras Exhibit A as the Adjacent Way. The paved roadway referenced in the other affidavits also apparently corresponds to the Adjacent Way. [Note 40] Plaintiffs argue that this history of use confirms the Deeded Easement was relocated and that Defendant has no right now to obstruct the Adjacent Way.

The intentions manifested by both parties conduct are central to Plaintiffs claim that the Deeded Easement was relocated. An

easement may be deemed relocated when the conduct of the parties is such as to permit a conclusion that a different easement had been substituted for the way mentioned in the deeds because the evidence reflects a tacit understanding or an implied agreement, manifested by the dominant owner's acquiescence in the use of the different easement in lieu of the original for a number of years. Proulx v. D'Urso, 60 Mass. App. Ct. 701 , 705 (2004) (quoting Anderson v. DeVries, 326 Mass. 127 , 132-33 (1950)).

In spite of this language in Proulx, an implied agreement resulting in the relocation of an easement is not manifested in every case solely by the dominant owners acquiescence. In Proulx, it was appropriate for the court to focus on the dominant owners acquiescence because that case involved a dominant owners argument that he had not agreed to a relocation of an easement. In fact, the Proulx court found that the facts showed not merely passive acquiescence on the part of the dominant owner, but his affirmative and willing participation in the relocation process by further obstructing the original easement, actively improving the alternative right of way for his own benefit, and using that way as his exclusive access . . . for a decade. Id. As the Proulx court found, the dominant owners activity affirmed the servient owners blockading and degrading to a state of impassability the original easement. [Note 41] See id. Therefore, the relocation of the easement in Proulx is based on an implied agreement reflecting the conduct of both parties. Significantly, Proulx borrows the language of Anderson, in which the court found that one party was content with the acquiescence of the other party to use a certain way instead of a non-existent way described in a deed; in other words, both parties acquiesced, one to using an alternate way and one to a particular alternate way being used. See Anderson, 326 Mass. at 132. Proulx also relies in part on Desotell v. Szczygiel, 338 Mass. 153 , 158 (1958), in which the servient owner apparently acquiesced in the dominant owners use of a roadway during a six-year period, resulting in relocation of the easement. In short, this court must take into account the intent of both parties, as shown by their conduct, when considering whether the Deeded Easement was relocated.

The approval of the Agreement for Judgment, discussed supra, indicates that neither Union Square nor Defendant had any intent to relocate the Deeded Easement (or that such intent was superseded), except insofar as the Agreement for Judgment relocated it. The easement prescribed by the Agreement for Judgment is not the Adjacent Way.

It might be argued that the parties implicitly agreed to relocate the easement since June 20, 2005, the date of the Agreement for Judgment. [Note 42] Such a relocation would be from the Agreed Easement rather than from the Deeded Easement. The summary judgment record contains no evidence that Defendant agreed to relocate the Agreed Easement to the Adjacent Way, [Note 43] except to the extent that Defendant allowed Union Square to use the Adjacent Way, [Note 44] as alleged in the above-referenced affidavits. In fact, if Defendant has obstructed the Adjacent Way by painting parking stripes and installing granite curbing, Defendant clearly does not agree that the Agreed Easement was relocated.

The exact date that Defendant allegedly obstructed the Adjacent Way and the exact location of the obstruction is not clear from the summary judgment record. The Gibbons Affidavit, the Camapagna Affidavit, and the Mallard Affidavit all state in the same language: The granite curbing and parking lot stripes which were placed on the access road within the last couple of years[] have made truck passage impossible in this area. Xarras Affidavit 2 states:

15. The Plaintiffs tenants have complained in writing to the Plaintiff indicating that their trucks are encountering great difficulty accessing and leaving their businesses because of the activities at the Defendants property.

16. A copy of the letter dated January 20, 2009 from Resource Alliance, Inc.; the letter dated January 29, 2009 from LaserShip; and the letter dated January 30, 2009 from Leominster Floor Covering, Inc. are attached hereto as Exhibits B, C and D respectively.

The letters from Lasership and Leominster Floor Covering, Inc. to Xarras referenced by Xarras Affidavit 2 (Xarras Exhibit C and Xarras Exhibit D) both state in the same language:

As you are well aware, for the last several months, our trucks have encountered great difficulty entering and leaving the leased premises. This is due to the increased parking and related activities by the occupants and customers of [the Present Building]. . . . In addition, the owners of [Defendant Property] have installed granite curbing along Lancaster Street which further prohibits our ability to access and leave the leased premises.

The letter from Resource Alliance, Inc. to Xarras referenced by Xarras Affidavit 2 (Xarras Exhibit B) states:

As discussed, over the past several months, common carrier trailer truck drivers and their companies have complained to me of difficulties entering and leaving the access way to our premises. . . .

At [the Present Building] there are always an excess number of parked vehicles during the afternoon hours which . . . block and hinder safe passage of trucks to and from our business. . . . [T]raffic is unable to pass through [the right side of the entrance] due to street side granite curbing installed which prohibits access . . .

These affidavits and exhibits from Plaintiffs indicate that the Adjacent Way became blocked several months before January 20, 2009, or a couple years before November 18, 2010, about the time the Complaint in this case was filed. The time between the Agreement for Judgment and the alleged obstruction would therefore be at most a little over three years, a rather short time for Defendant to change its opinion about the location of the Agreed Easement, of which it was a beneficiary and which had been the result of recent litigation.

Furthermore, Plaintiffs affidavits do not indicate any use of the Agreed Easement. Instead, they allege consistent access to the Union Square Property by way of the Adjacent Way from 1970 to 2010. It seems highly unlikely that Union Square or its predecessor would agree in the Agreement for Judgment to end a thirty-five year period of use of the Adjacent Way, only to immediately resume such use.

Moreover, the Agreement for Judgment required the parties to widen the paved area and construct a retaining wall; any implied agreement to relocate the easement must have occurred after that work was completed, at a date later than the Agreement for Judgment. The Cosimi Affidavit states: [Note 45]

7. I had discussion on several occasions with James Xarras regarding the improvements pursuant to the [Agreement for Judgment] and received his permission and consent to make the necessary improvements to the [Agreed Easement]. Additional improvements were made which James Xarras agreed to share in paying the expense [sic].

8. The improvements were made to the [Union Square Property], pursuant to said Judgment and with the Plaintiffs [sic] consent. . . .

10. The Plaintiff has used and benefited [sic] from the easement established pursuant to the Agreement for Judgment.

It is by no means clear that Union Squares alleged use of the Adjacent Way and Defendants alleged acquiescence to such use have occurred long enough to warrant relocation of the Agreed Easement to the Adjacent Way, even assuming arguendo that both have occurred. Although no specific duration of the parties relevant conduct is required to relocate an easement, Union Squares alleged use of the Adjacent Way between the date of the Agreement for Judgment and the date at which Defendant allegedly obstructed the Adjacent Way is significantly less than the ten years in Proulx or the six years in Desotell.

The summary judgment record contains no evidence that Highland Manor has used the Adjacent Way. [Note 46] The affidavits presented by Plaintiffs refer only to truck traffic connected with Union Square. Therefore, it is impossible for this court to find any tacit understanding or implied agreement between Highland Manor and Defendant that would deem the easement relocated to the Adjacent Way.

Based on the foregoing, I find that there was no relocation of either the Deeded Easement or the Agreed Easement to the Adjacent Way.

. Prescriptive Easement.

Plaintiffs also argue in the alternative that they have acquired an easement by prescription in the Adjacent Way, by virtue of their ongoing adverse use.

An easement by prescription requires open, notorious and adverse use for twenty years over the land of another. Uliasz v. Gillette, 357 Mass. 96 , 102 (1970). Regardless of the nature of Union Squares use of the Adjacent Way, it has not satisfied the statutory time requirement for a prescriptive easement. The time of adverse use would accrue from the Agreement for Judgment, which was dated June 20, 2005, much less than twenty years ago. Therefore, Union Square cannot acquire an easement by prescription; it is not necessary to consider its use with respect to the other requirements for a prescriptive easement.

As discussed, supra, the summary judgment record provides no evidence pertaining to Highland Manors use of the Adjacent Way. Therefore, Highland Manor cannot acquire an easement by prescription. [Note 47]

Based on the foregoing, I find that Plaintiffs do not have an easement by prescription.

Trespass.

In Count III of their Complaint, Plaintiffs allege: From on or about 2004 to the present date, the Defendant, without lawful authority, installed or caused to be installed electrical service cable on the Plaintiffs property at 511 Lancaster Street, Leominster, Massachusetts. Defendant denied this allegation in its Answer. Neither party has put anything else before this court relative to Plaintiffs allegations of trespass. [Note 48] Therefore, this court is unable to make any findings or rulings with regard to Plaintiffs allegations of trespass.

As a result of the foregoing, I ALLOW Defendants Motion for Summary Judgment and DENY Plaintiffs Cross-Motion for Summary Judgment.

Inasmuch as the Agreed Easement continues to provide access to the Union Square Property according to the terms of the Agreement for Judgment, within thirty days from the date of this Decision the parties shall prepare a recordable plan indicating the location and dimensions of the Agreed Easement, including, but not limited to, its width and northerly boundary. [Note 49]

Since this court finds that Union Square and Defendant remain bound by the Agreement for Judgment and that there has been no relocation of the easement to the Adjacent Way, it is not necessary to address Plaintiffs allegations that Defendant has obstructed the Adjacent Way or to determine exactly where and when such obstruction allegedly occurred. Plaintiffs allegations of obstruction are moot, except as they may regard obstruction of the Agreed Easement, (although it is not clear from the summary judgment record that they do). Therefore, within thirty days from the date of this decision, Defendant shall remove any obstructions including, but not limited to, curbing or striping that impair Union Squares access to the Union Square Property by way of the Agreed Easement or Defendants access to Defendant Property by way of the Agreed Easement.

Judgment to enter accordingly.

Exhibit A

FOOTNOTES

[Note 1] Plaintiffs motion was submitted together with an Affidavit of James L. Xarras (Xarras Affidavit 1) and letters from tenants Resource Alliance, Inc., LaserShip, and Leominster Floor Covering, Inc., expressing dissatisfaction with access to their businesses. On February 9, 2009, Defendant filed an Opposition to Plaintiffs Motion for Temporary Restraining Order, together with supporting memorandum and Affidavits of James S. Whitney (Whitney Affidavit 1), Barry Cosimi (the Cosimi Affidavit), and Michael Lamarche (Defendants Tenant).

[Note 2] On February 26, 2010, Plaintiffs Attorney John M. Dombrowski, Esq., filed a Notice of Withdrawal of Appearance, and Plaintiffs Attorney James M. Cahn, Esq., filed a Notice of Appearance.

[Note 3] The affidavit titled Second Affidavit of James S. Whitney is actually the third affidavit by James S. Whitney, including the affidavit filed in opposition to the withdrawn Motion for a Temporary Restraining Order.

[Note 4] The 1946 Plan contains five sheets: one sheet that shows the entire plan and four numbered sheets showing areas in greater detail. (It appears that the five sheets of the 1946 Plan are designated 77.9A through 77.9E, but not all such labels are visible in the record.) The 1946 Plan shows a large industrial complex divided among six owners. It identifies multiple buildings, gravel roads, and paved areas. It also shows a network of water and sewer lines, an incinerator, a dam, ponds, and a tunnel system.

[Note 5] Recorded with the Registry at Book 625, Page 304 is a vote taken by the Board of Directors of the Leominster Manufacturers Trust, Inc. to grant deeds of easement dated December 10, 1946 to: Wachusett Realty Co., Inc., Combs, Inc., Lionel B. Kavanagh and Lester T. Sawyer, Plastic Turning Co., Inc., Lester T. Sawyer, Pyrotex Leather Company. Corresponding quitclaim deeds were dated December 11, 1946.

[Note 6] The Menchi Deed, which predates the 2004 Plan, describes Defendant Property as [a] certain tract of land . . . on the southwesterly side of Lancaster Street and on the northerly side of Fall Brook, but does not identify the boundaries of Defendant Property by reference to a plan. More particularly, the Menchi Deed describes Defendant Property as follows:

Beginning at the most southeasterly corner thereof at land conveyed by Anna Tata to Roland J. Bouvier et ux by deed dated July 16, 1951, recorded in . . . [the] Registry . . ., Book 688, Page 381, and at a point where the earlier sideline of Lancaster Street intersects the thread of Fall Brook, said point measuring 111.14 feet, more or less, northerly along said sideline from a stone bound at the northerly corner of the intersection of Lancaster and Malburn Street;

Thence running southwesterly to westerly as the thread of the brook existed at the time of the above-mentioned deed, 200 feet, more or less, to a corner at land now or formerly of Plastic Turning Co.;

Thence running by last named land, North 18° 21' West 172.74, 172.24 feet, more or less to a stake in the corner and North 37° 34' East 109.00 feet to a stake in the easterly sideline of Lancaster Street as laid out by the City of Leominster in 1896;

Thence by last named sideline the following five courses;

South 52° 25' East 44.57 feet to an angle;

South 45° 15' East 61.18 feet to an angle;

South 39° 11' East 61.05 feet to an angle;

South 32° 05' East 61.33 feet to an angle;

South 24° 15' East 11.59 feet, more or less, to the point of beginning.

The Menchi Deed states that the premises it conveys are the same premises conveyed . . . by deed of LPI Corporation dated April 23, 1992 and recorded with . . . [the] Registry in Book 2208, Page 001.

[Note 7] In addition to property labeled as the Plastic Turning Co. Inc. on the 1946 Plan, the Union Square Property contains two small parcels shown on the 1946 Plan as abutting such property on the west and labeled 39810 SQFT and 16438 SQFT.

[Note 8] The 1980 Plan is not part of the summary judgment record.

[Note 9] As shown on the Page 1 (77.9B) of the 1946 Plan, the Gravel Way continues westerly past the north side of another apparently similar building labeled 2A and 2B, which is also no longer standing. It then branches out and proceeds both westerly in a loop around an incinerator building and northwesterly, where it joins a network of paved roads serving the Highland Manor Property. As shown on the 1946 Plan, the Gravel Way provided some access to the south side of the Former Building and surrounded the building labeled 2A and 2B.

[Note 10] Defendant presents five exhibits to the Affidavit of Larry R. Sabean that compare Defendant Property as it exists today with Defendant Property as it was in 1946: Exhibit A - Existing Buildings in Leominster, Massachusetts; Exhibit B - 1946 Building Overlay in Leominster, Massachusetts; Exhibit C - 1946 Buildings in Leominster, Massachusetts; Exhibit D - Google Map in Leominster, Massachusetts; Exhibit E - Map With 1946 Buildings in Leominster, Massachusetts. Plaintiffs apparently do not object to these exhibits and have adopted most of Defendants Concise Statement of Material Facts and Legal Elements, which relies on these exhibits.

[Note 11] It is not clear from the summary judgment record whether the Former Building was expanded into or replaced by the Present Building.

[Note 12] The Present Building extends south nearly as far as Fall Brook, shown on both the 1946 Plan and the 2004 Plan.

[Note 13] The summary judgment record does not indicate the exact date from which the Present Building has occupied its current location. However, given the parties agreement that the Present Buildings size and location have not changed for at least forty years, that date does not affect this Decision.

[Note 14] Union Square acquired the Union Square Property in a Foreclosure Deed from T.D. Banknorth, N.A., which held a mortgage from UPRC to Safety Fund National Bank dated June 24, 1996 and recorded with the Registry at Book 2872, Page 10.

[Note 15] On October 27, 2004, an action was brought against Defendant in the Land Court by UPRC, Union Squares predecessor in title. In its Verified Complaint, UPRC requested that this court

[o]rder and declare that Plaintiff has an easement by prescription over that portion of Defendants property described as follows:

Beginning at the most easterly point of the UPRC Property at a point on the westerly side of Lancaster Street;

Thence South 24° 34' 0" West for a distance of 102.57 feet along a common boundary with the Whitney Property to a point at common Property of UPRC, Whitney, and property shown as Merchants National Bank on said Plan;

Thence easterly along the northerly side of the building located on the Whitney Property to a point on the westerly sideline of Lancaster Street;

Thence northwesterly along the westerly sideline of Lancaster Street to the point of beginning.

[Note 16] The Agreement for Judgment stated that the parties

agree to the following terms as a resolution to the pending Civil Action pending in Land Court Docket Number 303265 as follows:

1. line of right of way on defendants land located two feet down from building corner then five feet out from building to run to Lancaster Street to be shown on drawing to be attached.

2. defendants will widen and excavate Plaintiffs land to a width of 10 feet from existing pavement so as to widen existing paved are [sic] and make a common driveway to be shown on a plan to be recorded at registry of deeds . . .

4. The parties agree to enter into a reciprocol [sic] easement over their respective properties for access to both properties and plaintiff releases any right of claim to area outside of created way . . .

7. A reciprocal easement agreement, with a sketch or plan attached, shall be recorded at the registry of deeds. . . .

8. This Agreement for Judgment takes effect as a judgement on the merits, with prejudice, waiving rights of appeal and costs.

The term reciprocal easement as used in the Agreement for Judgment apparently means that the access way extended on both sides of the property line, that each party gave the other the right to use the part of a shared access way on its side.

[Note 17] The parties clarified at oral argument that the Agreed Easement is similar but not identical to an easement (the Similar Easement) labeled EXISTING RIGHT OF WAY EASEMENT on the 2004 Plan and defined on the 2004 Plan by a solid and a dashed line, as well as on Defendants exhibits by dashed lines. The Similar Easement is seventeen feet wide. The summary judgment record does not contain any deeds relative to the Similar Easement. The parties assert and agree that it is a deeded easement that benefits property labeled LAND N/F BBA REALTY TRUST ROBERT BOLIO, TRUSTEE MAP 443-A, LOT 4 on the 2004 Plan. Such property abuts Defendant Property on the west and the Union Square Property on the south. Unlike the Agreed Easement, and as shown on the 2004 Plan, the Similar Easement exists only on Defendant Property and does not overlap onto the Union Square Property. The Similar Easement is not involved in this litigation.

[Note 18] As shown on the Sketch Plan, 10' in apparently means ten feet into the plaintiffs property, i.e., to the north, which would be an expansion of the paved area.

[Note 19] As shown on the Sketch Plan, Point A appears to be the intersection of the boundary of the paved area on the north and a line extending northerly from the westerly boundary of Defendant Property.

[Note 20] Plaintiffs do not explicitly represent that the Union Square Property has been accessed solely by the Adjacent Way. However, Plaintiffs state in their Concise Statement of Material Facts and Legal Elements that [f]or at least the last forty years, truck access to [the Union Square Property] has been via the Adjacent Way.

[Note 21] Since the Mallard Affidavit states that the affiants wife worked at Union Products until 2005, the extent and basis of the affiants personal knowledge after that date is uncertain.

[Note 22] Plaintiffs stated at oral argument that the Adjacent Way was best described as immediately adjacent to the Present Building.

[Note 23] The summary judgment record is unclear about the extent and nature of the parking and related activities along the northerly side of the Present Building. The summary judgment record is also unclear about when such parking and activities began. Xarras Affidavit 2 states: 14. . . . Defendant and its tenants, customers and visitors park and drop people off and pick them up in the area next to the [Present Building] . . .

However, Plaintiffs Complaint does not explicitly mention parking on Defendant Property; nor is parking addressed in the Answer. Plaintiffs produce the Gibbons Affidavit, the Camapagna Affidavit, and the Mallard Affidavit, all of which state that parking lot stripes which were placed on the access road within the last couple of years have made truck passage impossible. . . . Whitney Affidavit 2 states that [i]f restrained from using [Defendant Property] as it has been used in the past, [Defendant] and its tenants will lose 9 parking spaces . . . Moreover, Whitney Affidavit 3 states that [t]he parking spaces . . . to which plaintiffs object in this case have been in continuous existence on [Defendant Property] for more than thirty . . . years. In their Concise Statement of Material Facts and Legal Elements, Plaintiffs describe the parking spaces as newly lined.

As discussed, infra, the ambiguity in the summary judgment record does not need to be resolved, since this court finds that the rights of Defendant and Union Square were resolved in the Agreement for Judgment.

[Note 24] The summary judgment record is unclear about the exact location of the granite curbing and the date at which it was installed and who installed it. Plaintiffs Complaint states that Defendant is maintaining [the Present Building] . . . granite curbing and other improvements without right and is . . . hampering the free and unobstructed use of the [Deeded] [E]asement. This statement suggests that the granite curbing is in the same area as the Present Building and is important as a related obstruction to the Deeded Easement. Such a suggestion may explain the statement in Whitney Affidavit 3 that [t]he parking spaces and granite curbing (or other similar berms) to which plaintiffs object in this case have been in continuous existence on [Defendant Property] for more than thirty . . . years. Since Whitney Affidavit 3 discusses parking spaces and granite curbing together, it may refer to granite curbing used to define parking spaces.

On the other hand, Xarras Affidavit 2, following allegations relative to Defendants parking activities, states that Defendant has installed granite curbing at the street which further precludes any traffic from passing over the [Deeded] Easement or the area next to [the Present Building] (emphasis added). The use of the word further suggests that the curbing is a separate obstruction from the Present Building, an inference supported by Xarras Exhibit B (as hereinafter defined), which states: [T]here is snow piled high on the right side of the entrance which is a visibility hazard. Unfortunately, traffic is unable to pass through that area due to street side granite curbing installed which prohibits access during non-winter months. However, as one enters from Lancaster Street, the right side would be the northerly side, on the Union Square Property. Yet, in their Concise Statement of Material Facts and Legal Elements, Plaintiffs state that [i]n the past few years, the Defendant installed granite curbing along the border of [Defendant] [P]roperty and Lancaster Street.

As discussed, infra, the ambiguity in the summary judgment record does not need to be resolved, since this court finds that the rights of Defendant and Union Square were resolved in the Agreement for Judgment.

[Note 25] Plaintiffs do not appear to allege that Defendant has obstructed the Agreed Easement.

[Note 26] Plaintiffs appeared to suggest at oral argument but nowhere else that Union Square did not have knowledge of the Agreement for Judgment and therefore should not be bound by the Agreed Easement. Plaintiffs pointed out that Union Square acquired the Union Square Property on August 6, 2007, but the Agreement for Judgment was not recorded with the Registry until November 10, 2008. Nevertheless, after commencing the Prior Action, UPRC recorded a Memorandum of Lis Pendens with the Registry on December 9, 2004 at Book 5525, Page 270. Since this recording was a matter of public record connected to UPRC, Union Square had sufficient notice to be bound. Moreover, this court notes that neither party has addressed Union Squares lack of knowledge of the Agreement for Judgment in its briefs. In addition, it seems likely that Union Square obtained some knowledge of the Prior Action, inasmuch as when the Union Square Property was obtained by Union Square, the Agreed Easement was a primary means of access to the Union Square Property and was presumably being visibly used by UPRC; Union Square presumably continued UPRCs use of the Agreed Easement after acquisition of the Union Square Property. Furthermore, by virtue of its reciprocal character, the Agreed Easement burdened both properties, making it that much more discoverable.

[Note 27] Highland Manor was not a party to the Prior Action or the Agreement for Judgment.

[Note 28] For example, the Sketch Plan indicates that the building corner referred to in Section 1 of the Agreement for Judgment is the northwest corner, and that the line of right of way is the southern boundary of UPRCs easement and runs straight to a point on Lancaster Street three feet northwesterly of Pole 25K.

[Note 29] In effect, relative to the Deeded Easement, the Agreed Easement requires Plaintiffs accessing Lancaster Street to veer to the northeast, away from the Present Building, rather than continuing easterly through it.

[Note 30] See also Nauset Road, LLC. v. Chaves, 18 LCR 439 , 440 (2010) (Trombly, J.) ([P]rivity of estate exists between a grantor and a grantee.).

[Note 31] See also Thibbitts v. Crowley, 405 Mass. 222 , 225 n.5 (1989) (quoting Walsh v. Walsh, 116 Mass. 377 , 383 (1874) ( [A] decree made by consent of counsel, without fraud or collusion, cannot be set aside by rehearing, appeal, or review.)); Levy v. Crawford, 33 Mass. App. Ct. 932 , 933 (1992) ([A]n agreement for judgment serves as a waiver of all matters within the scope of that judgment.).

[Note 32] This court notes that Paragraph 4 of the Agreement for Judgment contains text cancelled by a line through it and indicating that the parties to the Prior Action will sign stipulation of dismissal with prejudice. Presumably this text was replaced by the related statement in Paragraph 10 of the Agreement for Judgment that it takes effect as a judgment on the merits, with prejudice, waiving rights of appeal and costs. The cancellation of the text suggests that the parties did not intend a stipulation of dismissal. A stipulation of dismissal is a valid and final judgment for the purposes of claim preclusion, but not for issue preclusion. See Jarosz v. Palmer, 436 Mass. 526 , 536 (2002).

[Note 33] Because this court finds that Union Squares claim to the Deeded Easement is barred, the parties arguments pertaining to abandonment, adverse possession, and a prescriptive easement are largely moot with respect to Union Square. However, these arguments apply to Highland Manor and will be considered in turn.

[Note 34] In the alternative, Defendant contends that even if Plaintiffs did not abandon the Deeded Easement, it was extinguished by Defendants adverse possession. As discussed, supra, Whitney Affidavit 2 asserts that Defendants building has been blocking the Deeded Easement and rendering the Deeded Easement unusable since the 1970s. Defendant argues that the existence of the Present Building shows that Defendant occupied the Deeded Easement openly, notoriously, adversely, and without interruption for more than twenty years. Defendant further argues that such occupation of the Deeded Easement was irreconcilable with the Deeded Easements use as a way. See Lemieux v. Rex Leather Finishing Corp., 7 Mass. App. Ct. 417 , 421-22 (1979) (requiring an element of adverse use . . . inconsistent with the continuance of the easement). Therefore, Defendant argues, it has acquired through adverse possession an unencumbered fee in the Deeded Easement. Both the abandonment and adverse possession theory have the same result and either can be applied here.

[Note 35] See also Dyer v. Key, 4 LCR 205 , 208 (1996) (Kilborn, J.) (Although . . . the . . . uses were not sufficient to establish extinguishment by prescription, the sufferance of them by the holders of the dominant estates can form part of the evidence of an intent to abandon.) (emphasis added).

[Note 36] Xarras Affidavit 1 alleges: As a direct and proximate result of the addition [transforming the Former Building into the Present Building], the Defendant has essentially unilaterally diverted all traffic to run in the area next to the addition and outside the [Deeded] [E]asement area. (emphasis added). Perhaps the phrase essentially unilaterally diverted is used for its arguable rhetorical force, but, to the extent that it is literally true, it poses problems for Plaintiffs arguments for mutual relocation.

[Note 37] The Union Products building was located on the Union Square Property.

[Note 38] Lasership is located on the Union Square Property.

[Note 39] This court notes that the Mallard Affidavit does not definitively state that the affiant himself traveled the Adjacent Way, at least by comparison to the other affidavits.

[Note 40] The Adjacent Way and the Agreed Easement are both paved, as is the area between them, forming a triangular paved area that fronts on Lancaster Street and is more than twenty feet wide in places. Therefore, the correlation of the paved roadway referenced in these affidavits to the Adjacent Way depends on its spatial relationship to the Present Building and the meaning of along the side of. However, any ambiguity in this language is moot, since this court finds that Union Square is bound by the Agreement for Judgment.

[Note 41] Signficantly, Plaintiffs argument from Proulx depends on the analogy to Defendants activity in blocking the Deeded Easement with the Present Building.

[Note 42] The parties do not appear to make this argument, since they focus on the Present Building as evidence of an intent to relocate the Deeded Easement.

[Note 43] Since the Agreed Easement was reciprocal and benefitted Defendant as well as Union Square, use of the Agreed Easement by Defendant would bear on Defendants intent. The summary judgment record shows little specific evidence of Defendants use of the Agreed Easement. However, the Cosimi Affidavit states that improvements pursuant to [the Agreement for Judgment] have allowed all parties to use and manage their respective properties without incident.

[Note 44] As a practical consideration, it is worth noting the subtlety of the difference between Plaintiffs use of the Agreed Easement and Plaintiffs use of the Adjacent Way. If Defendants alleged acquiescence in Plaintiffs use of the Adjacent Way amounts simply to allowing Plaintiffs to pass a few or several feet closer to the Present Building in the same general paved area, such acquiescence seems to be relatively weak evidence of a tacit understanding, by comparison to the blockading and degrading done by the servient owner in Proulx.

[Note 45] The Cosimi Affidavit states that the affiant is associated with [Defendant] and familiar with Defendant Property, the Union Square Property, and the Highland Manor Property, although the nature of the association is unclear.

[Note 46] The summary judgment record shows some inconsistency about whether Highland Manor alleges use of the Adjacent Way. Plaintiffs Statement of Material Facts states that the Adjacent Way has been used for truck access to the Union Square Property, but does not refer to Highland Manor or any other access by way of Defendant Property. On the other hand, Plaintiffs Complaint and Plaintiffs memorandum in support of its cross motion for summary judgment both use language that includes Highland Manor in the use of the Adjacent Way. Furthermore, Xarras Affidavit 2 states that all traffic accessing the Plaintiffs properties must now travel over [the Union Square Property].

[Note 47] The summary judgment record provides no evidence of how the Highland Manor Property is currently accessed, except for the statement in Xarras Affidavit 2 that traffic accessing Plaintiffs properties must travel over the Union Square Property. However, it appears from the summary judgment record, although this court does not now so decide, that Highland Manor has a valid easement pursuant to the 1946 Deeds to use the roadways shown on the 1946 Plan, except as otherwise decided in this Decision. Such roadways appear to include at least one paved way unblocked by buildings and running across the Union Square Property to Lancaster Street. In fact, access across the Union Square Property to the Highland Manor Property appears to be more direct and convenient than access to the Highland Manor Property by way of Defendant Property or by any way adjacent to Defendant Property.

[Note 48] The Cosimi Affidavit refers to improvements made to the Plaintiffs [sic] property, pursuant to [the Agreement for Judgment] and with the Plaintiffs [sic] consent[,] not by trespass as alleged in the Plaintiffs [sic] complaint. However, it is not clear what these improvements were or that they involved electrical service cable.

[Note 49] Attached to this Decision as Exhibit A is a copy of the Sketch Plan.

MARGOT XARRAS, TRUSTEE OF HIGHLAND MANOR REALTY TRUST and JAMES L. XARRAS, TRUSTEE OF UNION SQUARE REALTY TRUST v. JAMES S. WHITNEY, TRUSTEE OF 557 LANCASTER STREET REALTY TRUST

MARGOT XARRAS, TRUSTEE OF HIGHLAND MANOR REALTY TRUST and JAMES L. XARRAS, TRUSTEE OF UNION SQUARE REALTY TRUST v. JAMES S. WHITNEY, TRUSTEE OF 557 LANCASTER STREET REALTY TRUST