This case involves a contested complaint to register title to a parcel of land (the locus) in Orleans, Massachusetts. The plaintiff, Valerie Ruth Wester, seeks to register approximately 2.3 acres of land with an appurtenant fifteen foot wide right of way for travel and an easement for utilities, running northerly from the locus to Pond Road and shown on the updated file plan as "15'

R.O.W." (the right of way). The plaintiff also seeks to eliminate vehicle tracks located within the locus, which tracks are shown on the file plan (the vehicle tracks).

The original defendant, Lake Farm Camp, Inc., a corporation, (Lake Farm), [Note 1] filed an answer denying the plaintiff's claimed right of way and easement. Lake Farm also objected to the elimination of the vehicle tracks, claiming both rights of record and rights by adverse possession in said tracks. Lake Farm later amended its answer to include claim that it held record title to a portion of the claimed locus (shown as Parcel A on the Appendix and hereinafter referred to as Parcel A), alleging that due to a

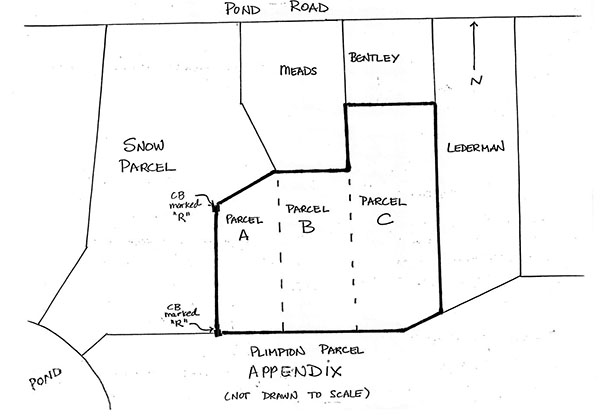

surveyor's error, this land had been omitted from a 1965 conveyance from Jeanne E. Snow to Lake Farm of a parcel of land to the west of the plaintiff's land. In its amended answer, Lake Farm claimed that it took title to Parcel A by a subsequent confirmatory deed from Snow to Lake Farm. Subsequently, at some point during the trial, the present defendants, Currier and Nale, enlarged their claim of title to a portion of the locus to include both Parcels A and B as shown on the Appendix, [Note 2] based on the opinion of their title expert, Henry Thayer (Thayer), that the plaintiff only had good record title to a one acre parcel. According to Thayer, this one acre parcel is formed by a southerly extension of the boundary between the parcels designated "Meads" and "Bentley" on the Appendix and is shown as Parcel C on the Appendix and referred to as Parcel C hereinafter.

In response to the registration complaint, Lake Farm [Note 3] instituted Land Court Miscellaneous Case No. 99198 against the plaintiff and her husband, John R.Wester, seeking a determination that it held record title to a portion of the locus (Parcel A) as well as having the right to use the vehicle tracks within the locus. In addition, Lake Farm sought damages for trees which the Westers had cut and removed from Parcel A. The Westers filed an answer denying that Lake Farm owned any portion of the locus and also denying that Lake Farm had any rights to use the vehicle tracks within the locus. [Note 4]

On the first day of trial, the defendants withdrew their objections to the plaintiff's claim of the appurtenant right of way. The defendants also withdrew their claims of any right to use the vehicle tracks over any land which was subsequently found to be owned by the plaintiff. After the trial had commenced, the Court became aware that the portion of land which had been owned

by Lake Farm over which the plaintiff claims the right of way to Pond Road had been conveyed to Jerome J. Focose and Karin O. Focose by deed dated October 25, 1979 and recorded at Book 3009, Page 239. [Note 5] The Focoses were notified of the plaintiff's claim of a right of way over their land and an attorney filed an appearance on their behalf. Shortly thereafter, by stipulation dated February 29, 1988, the Focoses withdrew their objection to the plaintiff's registration complaint. In addition, the Focoses stipulated that the plaintiff, her successors and assigns have the claimed appurtenant right of way for travel and the easement for utilities over their land northerly to Pond Road.

Thirteen days of trial were held at which a stenogrpher was appointed to record and transcribe the testimony. Twelve witnesses testified, two chalks were used and 83 exhibits, some with multiple parts, were introduced into evidence and are incorporated herein for the purposes of any appeal. Two other exhibits were marked for identification only. The defendants argued a motion for directed findings at the close of the plaintiff's case which the Court construed as a Mass. R. Civ. P. 41(b)(2) motion to dismiss and upon which the Court declined to render judgment until the close of all evidence in the case. The defendants renewed that motion at the conclusion of all evidence and the motion was taken under advisement.

Based on all the evidence I find the following to be the material facts:

PLAINTIFF'S CHAIN OF TITLE

1. The locus consists of approximately 2.3 acres of land and is more particularly described in the Complaint for Registration and shown on a plan of land entitled "Sketch Plan of Land in Orleans, Mass. Being an Update of Valerie Ruth Wester Petitioner's

L.C.P. 40303A", prepared by East Cape Engineering and dated June 4, 1987 (the revised plan). This plan is an updated version of the plaintiff's original file plan, Land Court Plan 40303A (the original plan). The disputed parcel is a portion of the locus, shown as Parcels A and B on the Appendix, containing approximately 1.3 acres of woodland to which the defendants claim title.

2. The earliest deed in the plaintiff's chain of title is a deed dated December 16, 1899 and recorded at Book 241, Page 452 from the heirs of Jonathan Higgins to Gilbert E. Ellis for five parcels of land (the 1899 deed). The fifth parcel in the deed is the one to which the plaintiff claims title (hereinafter the Ellis parcel) and which had been part of a larger tract of land bounded on the north by the town road, [Note 6] on the east by land of Joseph Taylor, on the south by land of Samuel Hurd and on the west by the pond and land of Willard Higgins. This deed describes the Ellis parcel as "[a] piece of land or sand hole situate in said Orleans and bounded as follows:-on the south by land of Samuel Hurd: on the east, north and west by other land of the grantors and containing one acre. . ."

3. Gilbert E. Ellis died testate on January 20, 1944. Under his will, the Ellis parcel passed to his son, Gilbert E. Ellis, Jr.

4. Gilbert E. Ellis, Jr. conveyed the Ellis parcel to Richard Rich and Ruth D. Rich by deed dated December 19, 1944 and recorded at Book 623, Page 257. [Note 7] In this deed, the Ellis parcel is described as being bounded on the east, north and west by land now or formerly of George H. Higgins et al. (heirs of Jonathan Higgins) and on the south by land now or formerly of Samuel Hurd. The deed states that the parcel contains one acre.

Prior to the Riches' purchase of the Ellis parcel, Rich [Note 8] walked the property with Grafton Howes, who was the real estate agent representing the estate of Gilbert Ellis, in order to assess the bounds of the propery. At that time, Howes pointed out what

he believed to be the bounds. No bounds were found at the northwesterly and southwesterly corners of the property but Howes

represented to Rich that these were the westerly corners of the property. Rich relied soiely on Howes' representations as to where the bounds of the property were, including the location of the westerly corners. To Rich, it looked as if there were old rotten posts at the northwesterly and southwesterly corners. Within a few days of his purchase, Rich put locust posts at these two corners. In 1949, Rich made concrete bounds marked with an "R" and placed them at the two westerly corners where the locust posts had been.

Rich always believed that he had purchased one acre of land from Ellis, Jr. and although he never had a survey done of the

property which he had purchased, Rich believed that the boundaries of his property were as pointed out to him by Howes before his purchase and which are the boundaries which the plaintiff claims.

5. Richard Rich and Ruth D. Rich conveyed the Ellis parcel to the plaintiff by deed dated October 4, 1950 and recorded at Book 779, Page 112. The deed describes and bounds the parcel conveyed as follows:

On the South by land formerly of Samuel Hurd and now of Marjory Plympton (sic)...On the East by land formerly of George C. Higgins and now of Lewis Delano...On the North by land formerly of George C. Higgins et al, now of Lewis Delano...and persons unknown. On the West by land formerly of George C. Higgins and now of persons unknown. Containing one acre more or less...

In this deed, the Riches reserved life estates in the Ellis parcel. Ruth Rich died on January 28, 1968. Richard Rich released any interest which he had in his life estate to the plaintiff by deed dated August 8, 1979 and recorded at Book 2965, Page 103.

6. In conducting the title examination in this case, the court-appointed title examiner, Joseph D'Elia (D'Elia), first traced the plaintiff's chain of title. Next, in order to determine the location and boundaries of the plaintiff's property, D'Elia boxed in the locus using plans and deeds for those parcels abutting the plaintiff's property. To box in the locus, D'Elia used the following deeds: a deed from Lewis H. Delano, Jr. and Agnes H. Delano to Melvin J. Lederman and Helen C. Lederman dated April 22, 1966 and recorded at Book 1333, Page 412 for that parcel abutting the locus to the east and designated "Lederman" on the Appendix; [Note 9] a deed from Alice G. McDonald to Raymond W. Bentley and Helen A. Bentley dated November 24, 1972 and recorded at Book 1765, Page 175 for a parcel abutting the locus to the north and designated "Bentley" on the Appendix; [Note 10] a deed from Mary C. Smith to Charles E. Meads and Bertha Meads dated July 12, 1951 and recorded at Book 788, Page 47 for a parcel abutting the locus to the north and designated "Meads" on the Appendix; [Note 11] a deed from Paul P. Henson, Jr., Trustee to Lake Farm dated May 22, 1969 and recorded at Book 1440, Page 507 for a parcel of land abutting the locus to the south and shown on the Appendix as the "Plimpton parcel" and a deed from Jeanne E. Snow to Lake Farm dated June 11, 1965 and recorded at Book 1301, Page 729 for a parcel of land abutting the locus to the west and designated the "Snow parcel" on the Appendix. D'Elia also used an unrecorded plan entitled "Plan of Land in Orleans, Mass. made for Jeanne E. Snow", prepared by Nickerson and Berger, Civil Engineers and dated November 1964 (the 1964 Snow plan) which is referred to in the 1965 deed from Snow to Lake Farm. [Note 12] The 1964 Snow plan shows the westerly boundary of the plaintiff's land as being in agreement with what the plaintiff claims it to be.

Based on his examination of the plaintiff's chain of title, these abutting deeds and the 1964 Snow plan, D'Elia prepared a sketch of the locus (which is included in the examiner's report which is an exhibit in this case) and determined that the locus was located substantially as shown on the original plan. D'Elia testified that each deed in the plaintiff's chain of title describes a one acre parcel of land and that the plaintiff held record title to a one acre parcel of land. However, he concluded that the plaintiff had good, registerable record title to the 2.3 acre locus. D'Elia did not feel that the deviation between the one acre recited in the deeds in the plaintiff's chain of title and the 2.3 acres found on the ground was significant because it was his experience in reviewing deeds from the late 1800s and early 1900s in the Orleans area that area recitations in these deeds were often understated because the owner wished to escape real estate taxation. Consequently, he gave no weight to the one acre area recitations in each deed in the plaintiff's chain of title. Therefore, D'Elia relied solely on the deeds to the abutting parcels and the 1964 Snow plan in determining the boundaries of the locus and in his determination that the plaintiff has title to 2.3 acres of land.

In conducting his title examination, D'Elia did not fully examine the back titles to these abutting parcels. On cross-examination, D'Elia was shown a document in the defendants' chain of title, a confirmatory deed dated April 14, 1980 and recorded at Book 3082, Page 334 from Jeanne E. Snow to Lake Farm. After review of this document, D'Elia testified that this document clouded plaintiff's title because it appeared to convey to the defendants a portion of the locus, Parcel A. Due to the existence of this deed, D'Elia testified that the plaintiff did not have registerable title to the locus. Based on this, D'Elia testified on cross-examination that the plaintiff's title was not fit for registration. But as the plaintiff's final rebuttal witness, D'Elia testified that after having reviewed all the evidence presented in the case, he was once again of the opinion that the plaintiff's title was fit for registration. Because D'Elia did not fully examine the back title in the defendants' chain and because he changed his opinion as to the registrability of the plaintiff's title several times during the course of the trial, I find his opinion that the plaintiff has record title to the locus as claimed to be of little aid to the Court and accordingly, give it little weight.

7. The plaintiff's surveyor, James Bowman (Bowman), located the locus on the ground using monuments which he found as well as deeds and plans for parcels abutting the locus. In 1978, Bowman surveyed the locus in order to prepare the file plan. In surveying the locus, Bowman first walked the boundaries with Richard Rich, who pointed out what he believed to be the boundaries of the locus. Bowman found two concrete bounds marked "R" at the two westerly corners of the claimed locus as well as the other monuments at the corners of the locus, all of which are shown on the original and revised plans. In addition, Bowman found three old sand excavations on the locus, two of which are located on Parcel C and one which is located on the disputed parcel, all of which are shown on the revised plan.

Bowman next ran the chains of title for Rich's property and for those parcels abutting the locus. Bowman found an inconsistency between the one acre stated in the deeds in the plaintiff's chain of title and the 2.3 acres found on the ground based upon found monuments and Rich's claimed ownership. Bowman did not resolve this inconsistency because he held to the monuments which he had found on his field survey of the locus.

In reviewing the deeds for the parcels abutting the locus, Bowman found what he considered to be a "pretty good fit" between the locus and the parcels to the east, north and south of the locus. As for that parcel to the west of the locus which had been conveyed to Lake Farm in 1965 by Snow, Bowman found an inconsistency between a deed in the Lake Farm chain of title and the concrete bounds marked "R" located on the ground at the westerly corners of the locus. Bowman found that Rich's claimed ownership and the bounds found at the westerly corners of the locus were inconsistent with a deed in the defendants' chain of title

from Gerard R. Crosby to Jeanne E. Snow, dated September 1, 1964 and recorded at Book 1270, Page 278. Bowman determined that the deed from Crosby to Snow appeared to convey a parcel of land which included a portion of the disputed parcel, Parcel A, and was therefore inconsistent with Rich's claimed ownership of the entire locus. However, Bowman found that deeds subsequent to the Crosby to Snow deed in the defendants' chain of title were consistent with the concrete bounds he found and with Rich's claim of ownership. Consequently, he ignored the 1964 deed which was inconsistent with the monuments which he found on the ground.

In preparing the original plan, Bowman also referred to the 1964 Snow plan. The 1964 Snow plan depicts the westerly boundary of the plaintiff's land as being in agreement with what the plaintiff claims it to be. This plan shows the two concretebounds marked "R" on the westerly corners of the land depicted as being that of the plaintiff.

In 1987, Bowman updated the original plan. There are a few differences between the original and revised plans. First of all, the revised plan depicts the three old sand excavations located on the locus which were not shown on the original plan. Secondly, a wetland shown as being partially on the southeasterly corner of the locus on the original plan is shown on the revised plan as being completely off locus and to the south. Finally, the revised plan shows an iron pipe on the southerly boundary of the locus in the approximate location where the wetland had been depicted on the original plan. Bowman had not found this iron pipe when he first surveyed the locus in 1978 and therefore, it was not depicted on the original plan. In performing the 1978 survey, Bowman did not cut through the briars on the southerly boundary where the wetland was shown on the original plan and where the pipe was found in 1987. Bowman testified that this pipe was a small pipe, loosely set in the ground. Bowman also testified that if the boundary between the Meads property and the Bentley property was extended southerly to the pipe, the parcel created to the east of this boundary would contain approximately one acre.

In reaching the conclusion that the boundaries of the plaintiff's property are as shown on the file plan and that the plaintiff has record title to the 2.3 acre locus, Bowman seems to have ignored any inconsistencies which he found and to have relied on the deeds in Lake Farm's chain of title subsequent to the 1964 Crosby to Snow deed, the 1964 Snow plan, Rich's representations as to where the boundaries of his land were and most importantly, what Bowman found on the ground as evidence of the lot corners of the locus.

I find that Bowman was mistaken in his heavy reliance on the monuments which he found and which Rich had pointed out to him. The two concrete bounds marked "R" which Bowman determined were the westerly corners of the locus were placed there by Rich because that was where Howes, the real estate agent who showed Rich the property, told Rich the corners of the property were. Rich stated that it looked as if there were old posts which had rotted out at these two corners. However, the 1899 deed bounds the Ellis parcel on the west by other land of the grantors and makes no reference to any posts as monuments. In addition, the fact that Howes believed these to be the westerly corners of the property and that in reliance thereon Rich placed concrete bounds at these corners does not require a finding that these were in fact the westerly corners of the property as originally conveyed to Ellis in 1899. If Howes was wrong as to the location of the westerly boundary, then Rich would also be wrong. Therefore, I do not find the location of the two concrete bounds to be determinative of where the westerly boundary of the plaintiff's land is located.

8. The defendants' title expert, Thayer, determined that the plaintiff only had title to a one acre parcel, parcel C, giving "quite a bit" of weight to the one acre area recitation in the plaintiff's deed. Thayer also ran the defendants' chain of title back and found that early deeds in the defendants' chain of title describe boundaries which are consistent with the plaintiff having title to a one acre parcel of land.

9. The defendants' surveyor, Albion Hart (Hart), did field work at the locus sometime between September of 1987 and February of 1988. In doing this field work, Hart found the iron pipe on the southerly boundary of the locus which is shown on the revised plan. In addition, Hart calculated that Parcel C contained approximately 1.02 acres.

DEFENDANTS' CHAIN OF TITLE

10. The defendants' predecessor in title, Lake Farm, acquired its first property in the vicinity of the locus from Margery Plimpton in 1957 (the Plimpton parcel). [Note 13] The Plimpton parcel consisted of approximately nine acres of land located south of the locus and had been the location of a summer camp since 1930. Subsequent to the 1957 purchase of the Plimpton parcel, Lake Farm made three additional purchases of abutting land. In 1961, Lake Farm purchased from Norman White two cranberry bogs abutting the Plimpton parcel to the southwest. In 1965, Lake Farm purchased the property to the west of the locus from Jeanne Snow (the Snow parcel). Finally, in 1977, Lake Farm purchased from Roger Young land which abutted the Plimpton parcel to the southeast. These three parcels became part of the Lake Farm Camp.

11. It is the 1965 Snow to Lake Farm conveyance which is relevant to this registration proceeding because it is from this conveyance which the defendants' claim of title to the disputed parcel stems. The Snow parcel was once part of the same tract of land owned by the estate of Jonathan Higgins out of which the Ellis parcel was conveyed. The first deed in the chain of title to the Snow parcel is a deed for a parcel of land (which the defendants claim included the disputed parcel) from the heirs of Jonathan Higgins to Isaiah Linnell dated January 29, 1901 and recorded at Book 384, Page 221 (the Linnell parcel). This deed describes the land conveyed as being bounded northerly by the town road, easterly by land of Gilbert Ellis, [Note 14] southerly by land of Samuel Hurd and westerly by the Pond and land of the heirs of Willard Higgins.

12. Linnell conveyed the Linnell parcel to Orville W. Crosby by deed dated January 31, 1901 and recorded at Book 392, Page 495. The description of the Linnell parcel in the deed to Crosby is as follows:

Commencing in the North East Corner of the Premises at a Marble Bound in Gilbert Ellis ways thence South Easterly in Ellis ways to Samuel Hurd ways thence Westerly in Samuel Hurd ways as the fence now stands to the Pond, thence Northerly by the Pond and the heirs of Willard Higgins to the road thence Easterly by the road to the first mentioned bound.

Although he was not familiar with the term "in...ways", Thayer concluded that the term had the same meaning as "in the range of" and that therefore the easterly boundary of the parcel conveyed was the same as in the deed to Linnell--the land of Gilbert Ellis--and I so find.

13. The next deed relevant to the defendants' chain of title is a deed for a parcel of land out of the Linnell parcel from Orville Crosby to William J. Corcoran and Emma M. Corcoran dated October 3, 1924 and recorded at Book 411, Page 174. The

description in this deed begins at the northeast corner of the premises conveyed and runs southerly in the range of Ellis for approximately 250 feet, thence westerly in the range of the land of the grantor for approximately 75 feet, thence northerly in the range of the land of the grantor for approximately 250 feet, to the road and thence easterly approximately 75 feet, to the place of beginning. This parcel was later conveyed by the administratrix of Emma Corcoran's estate to Charles E. Meads and Bertha Meads by deed dated July 12, 1951 and recorded at Book 788, Page 47 and is that portion of the Meads property to the east of a northerly extension of the boundary line between Parcels A and B on the Appendix.

14. Orville Crosby died intestate on November 1, 1929. By deed dated November 1, 1939 and recorded at Book 603, Page 196, Celia H. Crosby and Kenneth G. Crosby (heirs of Orville Crosby) conveyed to Gerard R. Crosby (also an heir of Orville Crosby) a parcel of land which included the Linnell parcel less so much thereof as was previously conveyed to the Corcorans. In this deed, the parcel conveyed to Gerard Crosby was bounded on the north by Pond Street, on the east by land late of William J. Corcoran, deceased, and by land now or formerly of Gilbert Ellis, on the south by land formerly of Samuel Hurd and by the waters of Crystal Lake or Fresh Pond, so-called and on the west by land of Mabel Ronne.

15. The next deed in the defendants' chain of title is from Gerard Crosby to Jeanne E. Snow dated September 1, 1964 and

recorded at Book 1270, Page 276 (the Snow parcel). This deed bounds and describes the land, in relevant part, as follows:

NORTHWESTERLY by Pond Road (Town Way) a distance of Six Hundred (600) feet, more or less; NORTHEASTERLY by land now or formerly of Charles Meads et ux and land now or formerly of Ruth Valerie Rich (sic) et al, a distance of Four Hundred Seventy (470) feet, more or less; SOUTHERLY by land now or formerly of Paul P. Henson, Jr., trustee, by two courses there measuring, a distance of One Hundred Forty-Five (145) feet, more or less, and a distance of Four Hundred (400) feet, more or less respectively...

16. By deed dated June 11, 1965 and recorded at Book 1301, Page 729, Snow conveyed the Snow parcel to Lake Farm. That part of the parcel as is relevant to the disputed parcel is bounded and described as follows:

Northwesterly by Pond Road, a town way...Easterly by Parcel C, [Note 15] one hundred sixty and 11/100 (160.11) feet, as shown on said plan; Northeasterly by Parcel C, ninetyfive and 32/100 (95.32) feet, as shown on said plan; southeasterly by land now or formerly of Valerie Ruth Rich, one hundred fifty-four and 46/100 (154.46) feet, as shown on said plan; Easterly again by land now or formerly of Valerie Ruth Rich, a total distance of two hundred seven and 40/100 (207.40) feet, as shown on said plan; Southeasterly again by land now or formerly of Paul P. Henson, Trustee...Being a portion of the premises conveyed to me by deed of Gerard R. Crosby dated September 1, 1964 and recorded at Barnstable County Registry of Deeds in Book 1270, Page 276.

The plan referenced in this deed is the 1964 Snow plan. This plan shows the land of Rich as including the entire locus, including the disputed parcel.

17. Subsequent to the 1965 conveyance, Snow gave to Lake Farm a deed dated April 14, 1980 and recorded at Book 3082, Page 334 which describes a parcel of land the description of which is substantially the same as in the 1965 deed from Snow to Lake Farm with one exception. Instead of the parcel being bounded southeasterly by land of the plaintiff for 154.46 feet and then

easterly by land of the plaintiff for 207.40 feet as in the 1965 deed; the parcel is bounded northeasterly by land of the plaintiff for 220 feet. The stated purpose of this confirmatory deed was to convey a parcel of land which had been omitted from the original Snow to Lake Farm deed and which Snow had intended to convey to Lake Farm via the original conveyance. The deed further states that the omitted parcel was not included in the original deed because the description was taken from the 1964 Snow plan which mistakenly shows two bounds. These two bounds are the concrete bounds marked "R" depicted on the Appendix and on the original and revised plans.

18. Lake Farm Camp, Inc. was dissolved in June of 1986 and its property was deeded to its sole shareholders, the defendants, Currier and Nale, by deed dated June 4, 1986 and recorded at Book 5116, Page 309. The relevant part of the description of the parcel conveyed by this deed bounds the property northeasterly, then northwesterly, by the land of Jerome J. Focose et ux (a portion of the Snow parcel abutting the Meads property to the west and abutting Parcel A to the north, which Lake Farm had conveyed to Jerome J. Focose and Karin O. Focose in 1979 and which is shown as Lot 1 on a plan of land entitled "Plan Showing a Division of land in Orleans, MA. for Lake Farm Camp, Inc." prepared by Nickerson and Berger and dated October 5, 1979) and northeasterly by land of the plaintiff. The plan referenced in the deed from Lake Farm to the defendants depicts the parcel conveyed to the defendants as including Parcel A, but not Parcel B.

19. By deed dated June 5, 1986 and recorded at Book 5116, Page 311, the defendants conveyed a portion of their property to David B.Willard, Trustee of the Preservation Advocacy Trust. The relevant part of the description in this deed is the same as in the deed from Lake Farm to the defendants; that is, northeasterly and northwesterly by the land of Focose and northeasterly by the land of the plaintiff. The plan referenced in this deed was the same plan referenced in the deed from Lake Farm to the defendants and depicts the parcel conveyed to Willard as including Parcel A, but not Parcel B.

A condition of the sale to Willard was that title to the disputed parcel be cleared. Due to this registration proceeding, the defendants could not pass clear title to that portion of the property containing the disputed parcel. Accordingly, they reduced the purchase price of the entire parcel conveyed to Willard and in return, by deed dated August 18, 1987 and recorded at Book 5925, Page 155, Willard conveyed to the defendants lot 3 as shown on a plan entitled "Subdivision Plan of Land in Orleans, Massachusetts prepared for Preservation Advocacy Trust" dated January 30, 1987. This plan depicts lot 3 as including Parcel A, but not Parcel B.

20. By deed dated December 23, 1987 and recorded at Book 6150, Page 203, Willard conveyed to the defendants title to a parcel of land bounded northerly by the land of Meads for 75 feet, easterly by land which had been conveyed to Ellis by the heirs of Higgins, southerly by land of the grantor (which land was the Plimpton parcel which had been conveyed to Willard by the defendants) and westerly by land of the defendants, lot 3. This deed describes Parcel B. Although the defendants believed they already had title to parcel B under the deed from Willard to lot 3, this deed was obtained on Thayer's advice in order to get Willard "out of the picture", presumably so the issue of title to parcel B as between Willard and the defendants would not arise at a later date.

USE OF THE DISPUTED PARCEL BY THE PLAINTIFF

21. Within a few days after his purchase of the Ellis parcel in 1944, Rich placed locust posts at the northwesterly and southwesterly corners of the disputed parcel. Rich replaced these posts with concrete bounds marked "R" sometime around 1949. Other than placing these bounds at what he believed to be the corners of the westerly boundary of his property, Rich did not fence or otherwise enclose the locus at any time.

22. Beginning in the winter of 1945, wood was cut from the locus by either Rich's employee, Harold Crowell, or by Rich

himself. Although Rich occasionally cut wood from the locus, Crowell cut wood much more frequently. Rich saw Crowell cut wood from within the sand excavation located on the disputed parcel and also from an area on the disputed parcel to the north of the sand excavation. Rich remembered that almost all of the wood which he and Crowell cut from the locus was cut from the disputed parcel because the "good wood" was to the west of the vehicle tracks. Rich personally cut wood from the disputed parcel from approximately 1945 until approximately 1957. From 1945 until some time in the mid 1970s, Crowell cut wood from the disputed parcel three or four times each winter. In the winter months from 1957 until 1961, Martin Rich, brother of the plaintiff, worked with Crowell cutting wood on the disputed parcel. By 1961, most of the growth on the disputed parcel had been cleared and the frequency of the wood cutting thereon decreased, although Crowell continued to cut trees occasionally on the disputed parcel until the mid 1970s, when he had to cut back due to a heart condition.

The wood cut from the disputed parcel was put to several uses. Rich sold pine and oak cord wood cut from the disputed parcel from 1947 until 1957, when his wood business "petered" out. From 1945 until 1955, Rich personally used load wood cut from the disputed parcel. In addition, Crowell used some of the wood cut to heat his cottage which was located on that portion of the locus not in dispute, Parcel C.

During these years from 1945 until 1957 when Rich personally cut wood from the disputed parcel, he never saw anyone else cut wood from any part of the locus, including the disputed parcel. Rich never asked anyone for permission to cut wood from the disputed parcel and no one ever objected to his or Crowell's doing so.

23. The cottage in which Crowell lived was an oil house which Rich placed on Parcel C some time around 1950. An addition to the original oil house was constructed over a number of years and completed in 1966 or 1967. Crowell lived in this cottage from 1950 until his death in 1980. From 1950 until the time the addition to the cottage was completed, Crowell used the wood cut from the disputed parcel to heat his house with a wood stove. Electric heat was installed in the cottage after the addition was completed, so Crowell no longer used wood to heat his cottage after 1966 or 1967.

24. From 1945 until 1966, Rich went to the locus a few times a week to pick Crowell up for work or to drop him off at the cottage. On these visits, Rich drove over the vehicle tracks and did not walk around the rest of the locus. During his visits to Crowell over the years, the only portions of the locus Rich saw campers and counselors from Lake Farm use were the vehicle tracks. Rich did not see tents on any part of the locus.

25. The plaintiff's first contact with the locus was in 1956 or 1957 when the plaintiff was eight or nine years old. The plaintiff occasionally went to the locus as a child when her parents were either picking Crowell up or dropping him off at his cottage on the locus. On these visits, the plaintiff played on the locus. It is not clear from the testimony whether the plaintiff played on any part of the disputed parcel. The plaintiff moved from the Cape in 1964 to attend boarding school. From 1964 until she and her husband moved back to the Cape in 1978, the plaintiff did not personally engage in any activities on the locus. On her visits to the locus from 1956 or 1957 until she moved from the Cape in 1964, the plaintiff did not see anyone camping anywhere on the locus, although she did occasionally see children on the vehicle tracks in mid-summer.

The plaintiff and her husband cut wood from the disputed parcel in the spring and fall of 1978, the spring and fall of 1979 and the spring of 1980, mostly on Sundays. The plaintiff and her husband cut these trees to clear an area on the disputed parcel upon which they wished to build a house. The first time anyone objected to their cutting wood on the disputed parcel was sometime in 1979 or 1980 when the defendant Currier claimed she owned the land upon which the Westers were cutting wood. The Westers used the wood which they cut for a wood stove in their house in Brewster.

26. After Crowell died in 1980, the plaintiff fixed up the cottage and in 1981, rented to a tenant who resided at the cottage at least until 1988.

USE OF THE DISPUTED PARCEL BY THE DEFENDANTS

27. The defendant Currier first became associated with the Lake Farm camp when she became the director of the camp in 1957. The original grounds of the camp were located immediately to the south of the locus. Currier was the camp director at Lake Farm from 1958 until her retirement in 1984. The defendant Nale also became associated with the camp for the first time in 1957. From 1958 until 1984, Nale was a co-director of the camp. From 1958 until the camp was closed in 1984, the defendants operated the Lake Farm Camp for at least eight weeks each summer. The total number of campers, counselors and staff varied over the years from between 63 to 157 people each summer.

28. Throughout the summers from 1958 until 1984, various activities were conducted on the disputed parcel by campers and counselors. These activities included horseback riding, rainy day hikes, 'campcraft' overnight camp outs and camp 'specials'. Both defendants personally engaged in these activities on the disputed parcel throughout the years and also viewed campers and counselors engaging in these activities on the disputed parcel.

Horseback riding took place on the disputed parcel from 1958 until 1984 for at least one week each summer. Horses were ridden northerly on the vehicle tracks from the camp and then ridden to the west over the disputed parcel along a path which ran just northerly of the sand excavation located on the disputed parcel. On rainy days during the summers from 1958 until 1984, campers went hiking on the disputed parcel, usually along the same paths upon which the horses were ridden.

Campcraft was a type of nature study which involved the campers collecting and identifying different types of leaves. Campers collected leaves from all over the camp grounds, including the disputed parcel. As part of the campcraft activities, the campers also engaged in at least one major project each summer. In 1965, for example, the campers built a tower out of trees which they had cut down. The tower was not built on the disputed parcel but the white oak trees which were used for the tower were taken from the disputed parcel. Each summer from 1958 until 1984, campcraft activities took place on the disputed parcel at least once a week.

Overnight camp outs were conducted several times each summer from 1958 until 1984. These camp outs consisted of approximately ten campers with counselors who set up camp (sometimes with tents), lit a campfire, cooked dinner and spent the night either in tents or in sleeping bags under the open sky. Occasionally, these overnights took place on the disputed parcel.

From 1958 until 1984 at least some of the aforementioned camp activities took place on the disputed parcel on a weekly basis. The defendants did not ask anyone for permission to engage in these camp activities on the disputed parcel nor did anyone ever object to their doing so.

29. Although the defendants only operated the camp in the summer months, both defendants lived at the camp year round. In the off season, the defendants engaged in activities on the disputed parcel beginning in 1958. In the fall and spring from 1958 until 1971 or 1972, Currier took weekly walks over the disputed parcel. In the winters from 1958 until 1965, Nale collected plants on both the disputed parcel and the portion of the locus not in dispute. In the spring from 1958 until 1972, Nale cleared branches from the riding paths on the disputed parcel. While engaging in these activities on the disputed parcel other than in the summer, the defendants did not ask anyone for permission to do so, nor did anyone ever object to their performing said activities.

In a registration proceeding, the burden of proof is upon the plaintiff to establish title to the locus. Hopkins v. Holcombe, 308 Mass. 54 , 56 (1941). The plaintiff claims title to the locus under a chain of title commencing in 1899. Alternatively, the plaintiff claims title to the locus by adverse use and possession since 1945.

The first issue to be determined is whether the 1899 deed to Ellis conveyed title to the 2.3 acre locus as the plaintiff contends, or whether, as the defendants contend, the 1899 deed only conveyed a one acre parcel of land, Parcel C. The plaintiff essentially rests her claim of record title to the locus on the opinions of D'Elia and Bowman that she holds record title to the entire locus. Both of these opinions were based, not on the description in the deeds in the plaintiff's chain of title, but on monuments found on the ground as well as a review of deeds and plans for parcels abutting the locus. The plaintiff's reliance on these opinions is misplaced because I have already found these opinions to be flawed and of little help in deciding whether the plaintiff has record title to the locus. Because the plaintiff's claim of title to the locus stems from the 1899 deed which conveyed the Ellis Parcel to Gilbert Ellis, I must look at the language of the 1899 deed to determine what land was conveyed to Ellis.

To determine what land was conveyed by the 1899 deed requires a careful consideration of the description of the Ellis parcel in the 1899 deed. The 1899 deed describes the Ellis parcel as "[a] piece of land or sand hole situate in said Orleans and bounded as follows:-on the south by land of Samuel Hurd: on the east, north and west by other land of the grantors and containing one acre..." There are three components of this description which may be used to determine the location of the land conveyed. The first is the reference to "a piece of land or sand hole", the second is the bounding description and the third is the one acre area recitation.

The plaintiff maintains that the reference to the sand hole in the 1899 deed necessarily refers to the largest sand excavation on the locus which is located on the disputed parcel and that therefore, the Higgins heirs intended to convey the entire locus. The plaintiff, however, neglects to mention that there are two other sand excavations located on the locus and that both are located on parcel C. One of these appears from the revised plan to be a sizable sand excavation. Certainly, the reference to the sand hole in the 1899 deed could refer to one of the two excavations located on parcel C. No evidence has been presented concerning which sand hole the 1899 deed referred to. Therefore, I find no merit in the plaintiff's contention that the sand hole in the 1899 deed must be the sand excavation located on the disputed parcel.

I next consider the one acre area recitation in the 1899 deed. Thayer gave quite a bit of weight to the one acre recitation in reaching his conclusion that the plaintiff only held record title to a one acre parcel of land. The plaintiff, on the other hand, urges the court to disregard the stated one acre area. First of all, the plaintiff maintains that the area recited in a deed is given little weight by the courts in the construction of deeds. Secondly, the plaitiff relies on D'Elia's opinion that area recitations in deeds from the late 1800s and early 1900s in the Orleans area are generally unreliable and understated for tax reasons.

Generally, the area expressed is comparatively unimportant in the construction of a deed. Raymond v. Jackson, 297 Mass. 509 , 511 (1937). When there is a conflict within the description between the monuments and the area given in a deed, the general rule is that monuments are considered to be more indicative of the intent of the parties than is the area given and therefore, the monuments govern. Morse v. Chase, 305 Mass. 504 , 507 (1940). This rule of construction will be applied unless it would lead to a construction inconsistent with the intent of the parties. Holmes v. Barrett, 269 Mass. 497 , 500 (1929). In the present proceeding, the monuments given in the 1899 deed (land of Hurd and other land of the grantors) do not conflict with the one acre area recitation. The conflict is between the one acre area stated and the monuments found on the ground (the concrete bounds marked "R"), which monuments are not referred to in the 1899 deed. Because the monuments which conflict with the area are not referenced in the 1899 deed, there is no occasion to apply the rule that monuments govern an inconsistent area. Young Israel of Brookline, Inc. v. Peters, 346 Mass. 776 , 777 (1963). Accordingly, this rule provides no basis for disregarding the one acre area stated.

Although it may be true that area recitations in deeds from the late 1800s and early 1900s in the Orleans are often unreliable and understated for tax reasons, no evidence was introduced which indicates that the heirs of Higgins purposely understated the quantity of land they conveyed to Ellis in the 1899 deed. Additionally, the 1899 deed states that the Ellis parcel contains one acre with no qualifying language such as "more or less" or "by estimation", language which has been construed to mean that the quantity of land expressed in the deed is stated merely for descriptive purposes. Pickman v. Trinity Church, 123 Mass. 1 , 7 (1877). By implication, then, acreage recited without such qualifying language should not be considered a mere matter of description or estimation. Because none of the reasons for ignoring an area recitation is present in this case, I find the one acre area recitation in the 1899 deed to be an essential component of the description. Therefore, I rule that the Ellis parcel is a one acre parcel of land the boundaries of which must now be determined.

The 1899 deed describes the Ellis parcel as being bounded on the south by land of Samuel Hurd. The land of an adjoining proprietor is a monument. Holmes v. Barrett, 269 Mass. at 500. Therefore, the land of Hurd is a monument which provides a southerly boundary which can be located. The parcel is bounded on the east, north and west by "other land of the grantors." The

heirs of Higgins held title to a larger tract of land out of which the Ellis parcel was conveyed. The deed does not specify where

within the larger tract the Ellis parcel was located. This description of the easterly, northerly and westerly boundaries is so vague that it is impossible to locate the easterly, northerly and westerly boundaries by using the 1899 deed alone. All that I can conclude from the four corners of the 1899 deed is that the heirs of Higgins conveyed to Ellis a one acre parcel of land bounded on the south by the land of Hurd and surrounded on the other sides by land which the heirs retained.

In order to establish the location of the easterly, northerly and westerly boundaries, it becomes important to ascertain the location of the parcels adjacent to the plaintiff's land to the east, north and west. This can be done by using extrinsic evidence. Temple v. Benson, 213 Mass. 128 , 132 (1912). As of the time of the trial, the abutters of the plaintiff's land to the east were Melvin and Helen Lederman. Each deed in the Ledermans' chain of title bounds the property on the west by land of Ellis. There is no dispute as to the location of the easterly boundary of the plaintiff's land and therefore, I find that easterly boundary of the plaintiff's land is the Lederman land which is designated "Lederman" on the Appendix. The abutters of the plaintiff's land to the north were Raymond and Helen Bentley as of the time of the trial. Although not all of the deeds in the Bentleys' chain of title were introduced into evidence, the two which were introduced--the 1926 deed from Ellis to Smith and the 1972 deed from McDonald to Bentley--bound the parcel on the south by land of Ellis. There is no dispute as to the northerly boundary of that portion of the

locus referred to as Parcel C and I therefore find that the northerly boundary of Parcel C is the Bentley land which is designated "Bentley" on the Appendix.

The abutters of the plaintiff's land to the west are the defendants. Unlike the easterly and northerly boundaries where there is agreement as to the boundaries, the westerly boundary cannot be so easily determined because there is no agreement as to where the boundary lies. Because I have found that the Ellis parcel only contained one acre, the westerly boundary of the Ellis parcel must be located so that it creates a one acre parcel.

Bowman testified that if the boundary between the Bentley land and the Meads land were extended southerly to the iron pipe found on the southerly boundary of the locus, the resulting parcel to the east of this line would contain approximately one acre. The parcel so created by this boundary is what I have referred to in this decision as Parcel C. In addition, Hart calculated that Parcel C contained 1.02 acres. Finally, Thayer concluded that Parcel C was the one acre Ellis parcel. Based on the foregoing, I find that each deed in the plaintiff's chain of title conveyed only the one acre Ellis parcel and not any part of the disputed parcel. Therefore, I find and rule that the plaintiff only has record title to a one acre parcel, Parcel C and does not have record title to the entire claimed locus.

This conclusion is further supported by the fact that the defendants have demonstrated that they have record title to the disputed parcel as I hereinafter set forth. The first deed in the defendants' chain of title is a deed for a parcel of land, which I have referred to earlier in this decision as the Linnell parcel, from the heirs of Higgins to Isaiah Linnell and dated January 29, 1901. The deed described the Linnell parcel as being bounded northerly by the town road, easterly by the land of Gilbert Ellis, southerly by land of Samuel Hurd and westerly by the Pond and land of the heirs of Willard Higgins. The land of Gilbert Ellis to the east referred to in this deed is what is now the Bentley land as well as the Ellis parcel, Parcel C. The easterly line of the Linnell parcel was a line which began at the southerly line of Pond Road and ran southerly along the westerly boundary of the land of Bentley and continued southerly along the westerly boundary of Parcel C. Therefore, the Linnell parcel included the entire disputed parcel. By deed dated January 31, 1901, Linnell conveyed the Linnell parcel to Orville Crosby. Accordingly, as of this date, Orville Crosby held title to the disputed parcel.

The next deed in the defendants' chain of title is from two of the heirs of Orville Crosby to a third heir, Gerard R. Crosby, for a parcel of land including the Linnell parcel less so much thereof as was previously conveyed to the Corcorans. The Crosby to Crosby deed describes the parcel as bounded on the east by land late of William Corcoran and by land now or formerly of Ellis.

This description implies that the easterly boundary of this parcel is a straight line because the parcel is bounded on the east by land of Corcoran and of Ellis and no change of course is given. The only way in which the easterly boundary of this parcel would be a straight line was if the boundary ran southerly along the westerly boundaries of the Corcoran parcel and Parcel B, a boundary which would omit Parcel B from the conveyance to Gerard Crosby.

I have already found that Ellis only had title to parcel C. Therefore, a line running by the westerly boundary of parcel B would not bound on the land of Ellis. When a description appears to give a straight line because no change in course or direction is given but the description also bounds the land by a monument, wherever that monument is found to be located constitutes the boundary of the land conveyed. Curtis v. Francis, 63 Mass. (9 Cush.) 427, 439-40 (1952). The land conveyed will run as far as that monument, even if this is inconsistent with another part of the description in the deed. Clark v. Munyan, 39 Mass. (22 Pick.) 410, 416 (1839).

The deed from two of the Crosby heirs to Gerard Crosby bounds the parcel on the east by two monuments--the land of William Corcoran and the land of Ellis. When two monuments are given in a deed, the first monument is followed until the second is reached. Curtis, 63 Mass. (9 Cush.) at 645. At that point, it becomes necessary to seek the line of the second monument. Id. Therefore, the easterly boundary of the parcel conveyed to Gerard Crosby ran southerly along the land of Corcoran to its southwesterly corner at which point it becomes necessary to seek the line of Ellis' land, which I have determined is Parcel C. Curtis v. Francis, 63 Mass. at 465. To reach Ellis' land, the boundary of the parcel conveyed to Gerard Crosby would have to run from the southwesterly corner of the land of Corcoran easterly along the land of Corcoran until it reached Ellis' land and then run southerly along Ellis' land. This boundary includes the disputed parcel in the land conveyed to Gerard Crosby. I find this to be the true boundary of the land conveyed to Gerard Crosby and also find that Gerard Crosby took title to the disputed parcel under this deed.

The next deed in the defendants' chain of title is from Gerard Crosby to Jeanne E. Snow, dated September 1, 1964. This deed describes the parcel conveyed (the Snow parcel) as bounded northeasterly by land now or formerly of Charles Meads and land

now or formerly of the plaintiff for a distance of 470 feet more or less. As with the deed to Gerard Crosby, the easterly boundary appears to be a straight line because no changes in course are given. In addition, this literal description also appears to omit parcel B from the conveyance. However, because the parcel is bounded by the land of Meads and the land of the plaintiff, the call to the land of Meads and the plaintiff in the deed governs the course and distance stated, thereby conveying title all the way to the plaintiff's land and conveying title to the disputed parcel to Snow.

In 1965, Snow conveyed the Snow parcel to Lake Farm. The deed description bounded the parcel easterly by parcel C, [Note 16] northeasterly by parcel C, southeasterly by land now or formerly of the plaintiff and easterly by land now or formerly of the plaintiff. This literal description appears to omit title to the entire disputed parcel from the conveyance to Lake Farm. The description in this deed was based on an unrecorded plan of land which showed the land of the plaintiff as including both parcel C and the disputed parcel. However, I have already determined that the plaintiff does not have record title to the disputed parcel so this plan erroneously depicts the land of the plaintiff. Consequently, the literal description of the land conveyed to Lake Farm is also wrong. But as with the earlier conveyance from the Crosby heirs to Gerard Crosby and then from Gerard Crosby to Snow, the parcel conveyed to Lake Farm was bounded by the land of the plaintiff. Therefore, the deed carries title until it reaches the land of the plaintiff despite the inconsistent courses and distances. Accordingly, this deed actually conveyed the disputed parcel to Lake Farm although seemingly omitted from the literal description in the deed. Because of this, the 1980 confirmatory deed from Snow to Lake Farm was unnecessary and conveyed no interest.

The subsequent deeds in the defendants' chain of title--from Lake Farm to the defendants, from the defendants to Willard and

from Willard back to the defendants--each, where relevant, bound the land conveyed easterly by the land of the plaintiff. Therefore, each deed carried title to the plaintiff's land, parcel C, and carried title to the disputed parcel. Accordingly, I rule that the defendants have record title to the disputed parcel.

Because I have found that the plaintiff only has record title to Parcel C and the defendants have record title to the entire disputed parcel, any title the plaintiff has to the disputed parcel must rest upon the plaintiff's adverse use and possession of the disputed parcel. In order to establish title by adverse possession there must be proof of non-permissive use which is actual, open, notorious, exclusive and adverse for a period of twenty years. Ryan v. Stavros, 348 Mass. 251 , 262 (1964). The purpose of the requirements for adverse possession is to put the true owner on notice of the hostile character of the possession so that he may vindicate his rights by legal action. Ottavia v. Savarese, 338 Mass. 330 , 333 (1959). The burden of proving adverse possession extends to all of the elements of such possession and if any single element is left in doubt, then the claimant cannot prevail.

Mendonca v. Cities Services Oil Co. of Pa., 354 Mass. 323 , 326 (1968).

The plaintiff claims adverse use and possession of the disputed parcel beginning shortly after her father purchased the locus in 1944. The plaintiff took title to the locus in 1950. In order to establish the twenty years necessary for the acquisition of title by adverse possession, the plaintiff may tack the use by her predecessor in title, her father, Richard Rich, onto her years of possession. Buccella v. Agrippino, 257 Mass. 483 , 488 (1926). For the most part, any use of the disputed parcel was not made by the plaintiff herself or by her father, but rather, by her father's employee, Harold Crowell, who lived at the cottage located on parcel C from 1950 until his death in 1980. Because the possession of a tenant is the possession of the landlord, Wishart v. McKnight, 184 Mass. 283 , 286 (1903), the plaintiff may claim adverse use and possession of the disputed parcel through use by Crowell beginning in 1945.

The disputed parcel consists of approximately 1.3 acres of woodland. When the property claimed by adverse possession is woodland, there exists an additional requirement necessary to establish adverse possession and that requirement is that the woodland must be enclosed or reduced to cultivation. Cowden v. Cutting, 339 Mass. 164 , 168 (1959); Senn v. Western Massachusetts Electric Company, 18 Mass. App. Ct. 992 , 993 (1984). Although Rich referred to the disputed parcel as woodland during the trial, the plaintiff now maintains that Crowell's use of the cottage located on Parcel C as a residence takes the entire locus out of the category of woodland and renders inapplicable the additional requirement of enclosure or cultivation. However, the residence was located on that portion of the locus, Parcel C, which I have determined that the plaintiff does have record title to. The disputed parcel which the plaintiff claims title to by adverse possession is a parcel of woodland adjacent to, but separate from, the parcel to which the plaintiff has record title. Therefore, the presence of a residence on parcel C does not affect the disputed parcel's woodland status. In fact, this situation is strikingly similar to that in Cowden v. Cutting, where the claimant's predecessor in title had built and occupied a cottage on a parcel of land adjacent to the parcel claimed by adverse possession and

the Court found the claimed parcel to be woodland and applied the stricter test for the adverse possession of a woodland parcel. 339 Mass. at 167-8.

Neither the plaintiff nor her father ever enclosed the property in any way and although Rich did set two concrete bounds at the westerly corners of the disputed parcel, this hardly amounts to an enclosure. No evidence was offered of the cultivation of the disputed parcel. Further, the only use of the disputed parcel by the plaintiff, her father or Crowell was the yearly cutting of wood on the disputed parcel by Crowell, or occasionally by Rich, from 1945 until the mid 1970s and the cutting of wood by the plaintiff and her husband in the spring and fall of 1978, the spring and fall of 1979 and the spring of 1980. The cutting of wood, however, is insufficient to prove the adverse possession of a parcel of woodland. Senn v. Western Massachusetts Electric Company, 18 Mass. App. Ct. at 993, Cowden v. Cutting, 339 Mass. at 167-8.

Finally, even if the plaintiff had met the additional requirement necessary for the adverse possession of a parcel of woodland, the plaintiff's use of the disputed parcel was not exclusive, a requirement for the adverse possession of any type of land. The evidence is replete with instances of the use of the disputed parcel by the defendants and the campers and counselors from the Lake Farm Camp from 1958 until 1984, particularly in the summer months. These activities destroyed the continuity and exclusivity of the use and possession by the plaintiff. Mendonca v. Cities Services Oil Co., 354 Mass. 323 , 325-6 (1968) (where use of the disputed area by the record owner for a period of weeks interrupted the claimant's adverse possession thereof).

Accordingly, I find that the plaintiff has not acquired title to the disputed parcel by adverse possession and has title only to parcel C, to which she has record title.

Two final issues remain to be discussed-- the plaintiff's claim of an appurtenant right of way over the vehicle tracks not within the locus and the plaintiff's request that the Court eliminate the vehicle tracks within the locus. Because the defendants withdrew their objections to the plaintiff's claim of an appurtenant right of way running northerly to Pond Road and because the plaintiff has entered into a stipulation with the Focoses which gives the plaintiff this right of way over the Focoses' property, I rule that the plaintiff has the claimed appurtenant right of way northerly from Parcel C to Pond Road. Similarly, the defendants withdrew their objections to the elimination of the vehicle tracks within the land the plaintiff is found to own which I have found to be Parcel C. Because the defendants have withdrawn this objection, I rule that the vehicle tracks within Parcel C are hereby eliminated.

Based on the foregoing, I find and rule that the plaintiff has established registerable title to parcel C. Said judgment of registration is to be subject to such matters as are disclosed in the examiner's abstract which are not in issue. So much of the complaint as relates to the disputed parcel is severed and dismissed. The plaintiff's plan is to be updated and amended to reflect her lack of title to the disputed parcel.

Judgment of registration to issue accordingly.

W. Currier and Elizabeth P. Nale. On the first day of trial, Currier and Nale were substituted for Lake Farm as party defendants.

VALERIE RICH WESTER, a/k/a VALERIE RUTH RICH vs. MARION W. CURRIER and ELIZABETH P. NALE.

VALERIE RICH WESTER, a/k/a VALERIE RUTH RICH vs. MARION W. CURRIER and ELIZABETH P. NALE.