INTRODUCTION

Plaintiff William W. Thomas ("William, Jr.") [Note 1] brought this action on February 1, 2018 against defendants Eric S. Medeiros ("Eric"), Jeffrey M. Medeiros ("Jeffrey"), and The Estate of Ernest A. Medeiros ("the Estate"), claiming to be the owner of 75 Rogers Path, West Tisbury, Massachusetts, designated as Map 15, Lot 14 by the West Tisbury Assessor ("Lot 14" and "the Assessor," respectively); 613 State Road, West Tisbury, designated as Map 15, Lot 30 ("Lot 30") by the Assessor; and 64 Rogers Path, West Tisbury, designated as Map 22, Lot 45 ("Lot 45") by the Assessor (collectively, "the Subject Property"). [Note 2] The defendants disputed William, Jr.'s claims and asserted their ownership of the Subject Property.

The matter proceeded to trial on three issues: (1) could William, Jr. prove that he held record title to Lots 30 and 45, an issue that centered on whether a 1931 deed conveying property on Lambert's Cove Road, West Tisbury, formerly owned by one Jason Luce ("the Luce Homestead"), to William, Jr.'s predecessor in title and a subsequent 1955 deed conveying the Luce Homestead to William, Jr.'s parents, included the Subject Property; (2) could William, Jr. prove that he has possession of Lots 30 and 45; and (3) could Eric establish title by adverse possession if William, Jr. proved that he held record title to Lots 30 and 45. For the reasons set forth below, this court concludes that William, Jr. has failed to establish record title to or possession of Lots 30 and 45, and that an adjudication of Eric's rights cannot be had in the absence of other parties with an interest in Lots 30 and 45.

RELEVANT PROCEDURAL HISTORY

William, Jr.'s amended complaint, filed on December 5, 2018 ("Amended Complaint"), added The Resource, Inc. For Community and Economic Development ("CED") [Note 3] and repeated his claims from the original complaint for a writ of entry pursuant to G.L. c. 237, §1 et seq. (Count I), to try title pursuant to G.L. c. 240, §§1-5 (Count II), to quiet title pursuant to G.L. c. 240, §§6-10 (Count III), for a declaration of rights pursuant to G.L. c. 231A, §1 (Count IV), for equitable relief pursuant to G.L. c. 185, §1(k) to enforce whatever declaratory relief might be granted (Count V, really a remedy rather than a claim), and for trespass based on the Medeiroses' unauthorized entry (Count VI), all with respect to the Subject Property. By way of counterclaim, ("Counterclaim"), the defendants sought a declaratory judgment that Eric and Jeffrey are the owners of Lot 14 and that Eric is the owner of Lots 30 and 45 (Count I), to try title pursuant to G.L. c. 240, §1 (Count II), to quiet title pursuant to G.L. c. 240, §§6-10 (Count III), and to obtain an adjudication that Eric and Jeffrey hold title to Lots 14, 30 and 45 by virtue of their and their predecessors' in title adverse possession of the same (Count IV). By stipulation docketed on November 4, 2019, the parties agreed "for purposes of trial that Ernest A. Medeiros established title by adverse possession to [Lot 14]," leaving ownership of Lots 30 and 45 in dispute. As a result, Jeffrey and the Estate, whose interests are only in Lot 14, are no longer parties in interest in these proceedings.

This matter was tried over four days from November 18 through 21, 2019 on Martha's Vineyard. The court took a view of the Luce Homestead and the Subject Property. William, Jr., Ms. Patricia Szucs, a title examiner retained by him, and Ms. Lila DiBiaso testified on behalf of William, Jr. Eric, Police Chief Erik G. Blake, Ms. Margaret Medeiros St. Pierre ("Ms. St. Pierre"), Mr. Glen Pinkham, Mr. Kenneth Metell, Ms. Rebecca J. Cournoyer and Mr. Joseph F. Fontaine testified on behalf of Eric. The parties initially stipulated to 37 agreed exhibits, which were admitted in evidence. During the course of trial, another 17 exhibits were admitted. After the receipt of transcripts, the parties submitted post-trial briefs on March 13, 2020.

FINDINGS OF FACT

Based on the pleadings, the view, the admitted exhibits, the testimony at trial, as well as my assessment of the credibility, weight and inferences to be drawn therefrom, I find the following facts, reserving certain details and assessments of credibility for the discussion of specific legal issues. To the extent that any witness testified otherwise, I do not find that testimony credible, reliable, or in accord with the weight of the other testimony and exhibits in the case and the inferences I drew from the totality of that evidence.

The Parties

1. William, Jr., who was born in Abington, Pennsylvania on March 8, 1946, resides in Harrison, Maine, and has lived in Maine since 1999. Tr. I-100:20; I-103:17; I-112:17.

2. Eric, who was born on April 10, 1965, resides on Martha's Vineyard and is the grandson of Ernest S. Medeiros ("Ernest S.") and Evelyn M. Moniz ("Evelyn") and the son of Ernest A. Medeiros ("Ernest A.") and Ms. St. Pierre. Tr. III-160:25; III-204:2-4.

3. Jeffrey is Eric's brother, Tr. III-161:6, and was born in 1968. Tr. III-168:25.

The Relevant Properties

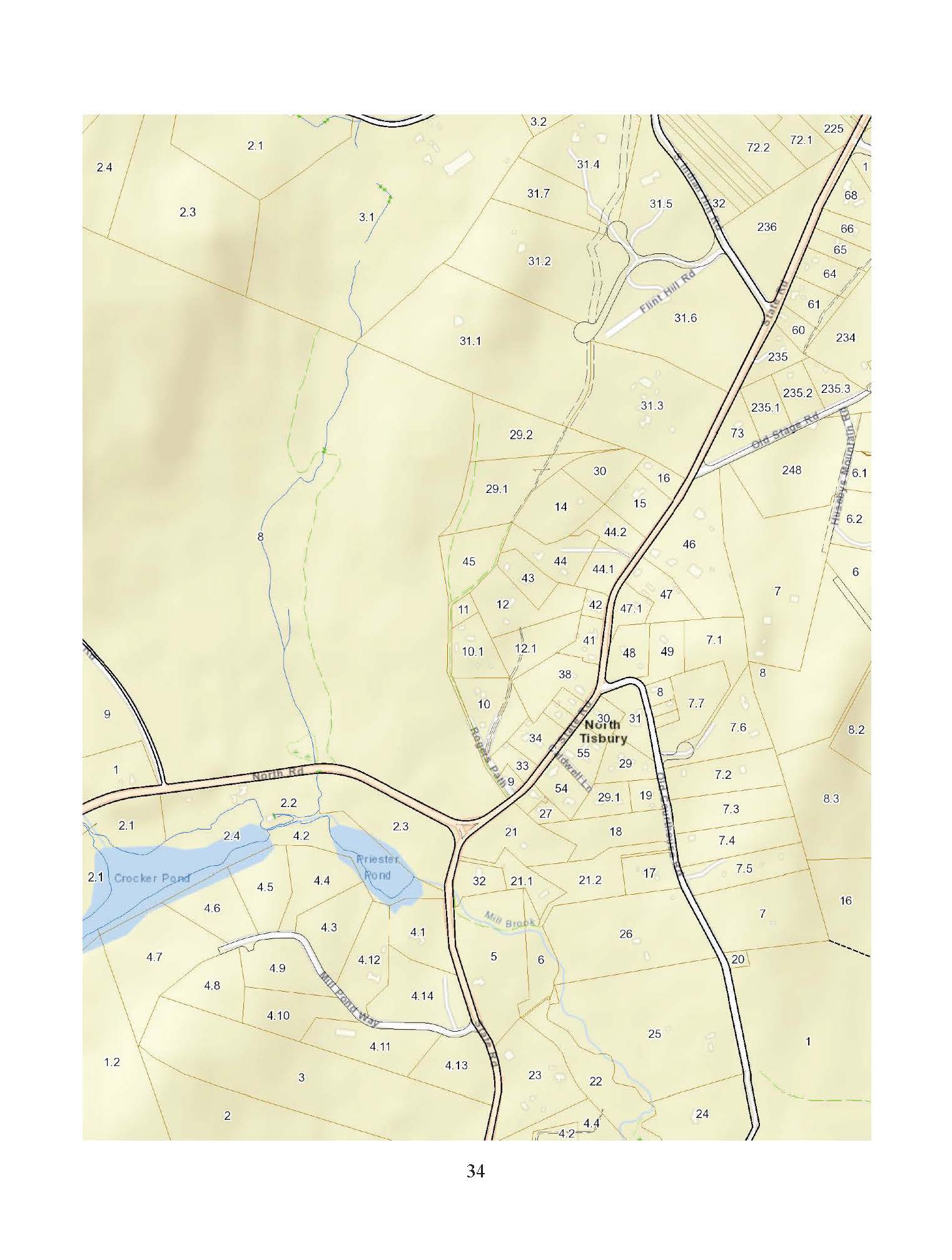

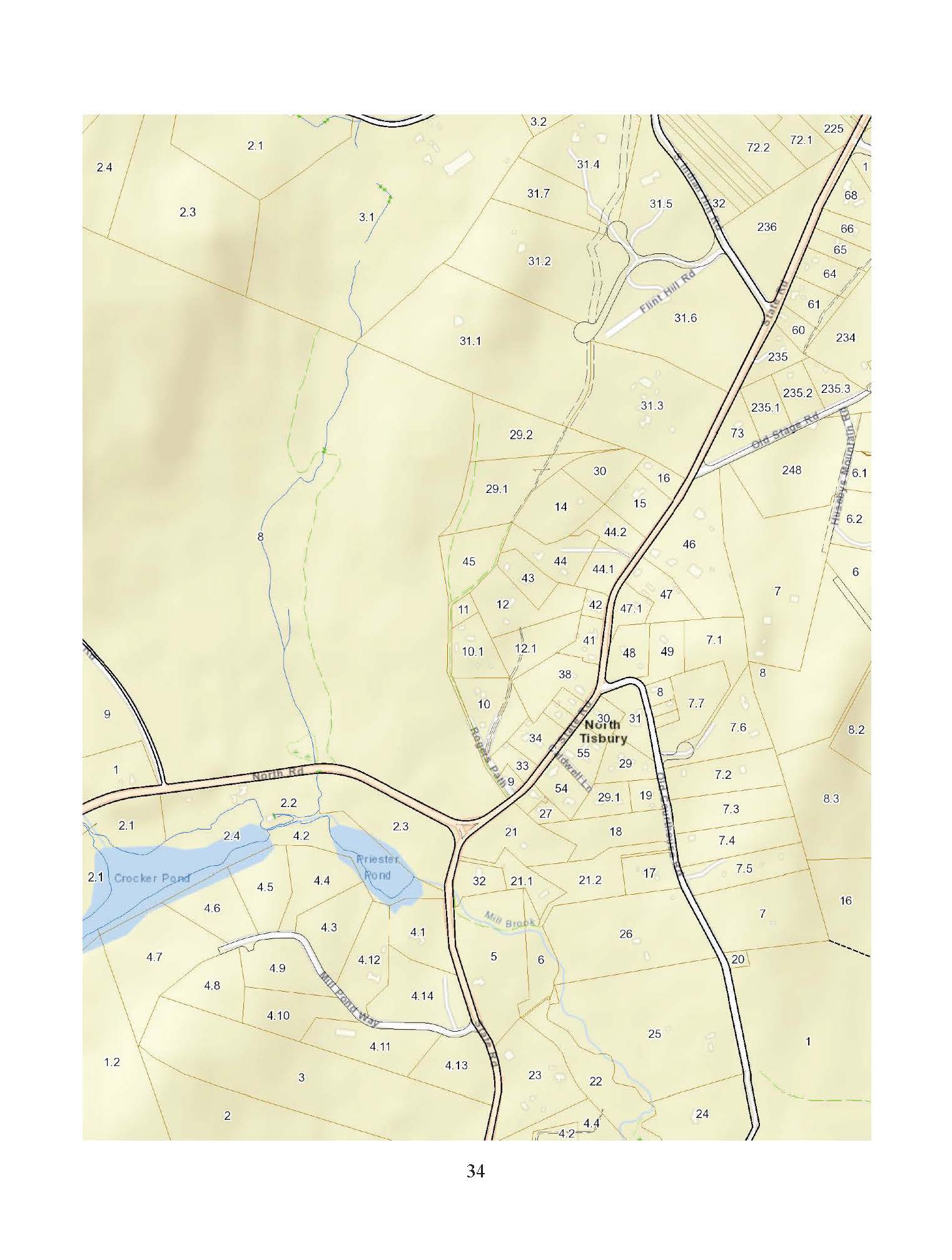

4. The properties at issue here are all on or near Rogers Path in West Tisbury, with the exception of the Luce Homestead, which is on Lambert's Cove Road in West Tisbury, some two miles away. Tr. I-167:4-19.

5. Rogers Path, which is a dirt, single lane road, leaves State Road in a northerly direction. Ex. 39.

6. To the west, Rogers Path abuts a large parcel designated on the Assessor's map as "Seven Gates Farm Corporation." Id.

7. To the east, Rogers Path abuts four lots not involved in this litigation before reaching Map 22, Lot 11, a cemetery owned by the Town of West Tisbury ("the Town"). Id.; Tr. I-32:4-13.

8. After the cemetery, Rogers Path veers to the east. Tr. I-32:24-25; I-33:1-9.

9. At that point, Lot 45 abuts Rogers Path to the west, as does a portion of Lot 29.1 before Rogers Path bisects the remainder of that lot and Lot 29.2. Exs. 1 and 39.

10. After the cemetery, Lots 12, 43, 44 and a portion of Lot 14 abut Rogers Path to the east. Id.

11. Lot 30 abuts Lot 14 along Lot 30's southwest line and abuts Lots 15 and 16 along its southeast line. Id.; Tr. I-144:6-7.

12. It is undisputed for purposes of these proceedings that: (1) William, Jr. owns Lot 29.1, Exs. 1, 25 and 39; (2) Ernest S. and Evelyn owned Lots 12 and 43, across Rogers Path from Lot 45, Exs. 1, 13 and 39; (3) Eric and Jeffrey own Lot 14, Exs. 1, 35 and 39; Tr. III-168:11; and (4) Lila DiBiaso and her husband own Lot 16, Exs. 1 and 39; Tr. II- 66:5-12; II-67:21-22.

13. A version of the assessor's maps for this area, available on-line at and reflecting the same material information contained in exhibits 1 and 39 marked at trial, is attached hereto as a chalk.

Title To The Luce Homestead

14. Record title to the Luce Homestead starts in this proceeding with two deeds, both dated August 30, 1871. One is from Edmund Luce and Arwin Luce to Jason Luce starting "at the Southeast corner two rods more or less from Peases Spring," and the other is from Edmund Luce to Jason Luce starting "at the Southwest corner about two rods from Peases Spring." Ex. 50; Tr. I-54:10-13; I-55:4-8.

15. Jason Luce died in 1904, leaving as his heirs his widow, Mary F. Luce ("Mary"), his daughters Adelia H. Cromwell ("Adelia") and Carrie M. Luce ("Carrie"), and his son, Edward F. Luce ("Edward"). Ex. 41.

16. Adelia deeded her interest in the Luce Homestead ("it being the home of my father the late Jason Luce deceased late of West Tisbury") to her mother, Mary, by deed dated December 14, 1904. Ex. 50.

17. Edward deeded his interest in the Luce Homestead ("all the real estate which I took by inheritance from my father Jason Luce deceased late of said West Tisbury") to Mary by deed dated March 5, 1907. Ex. 50.

18. Adelia's and Edward's deeds were both recorded on the same date: May 8, 1907. Ex. 50; Tr. I-89:7-21.

19. On August 7, 1931, Mary deeded to Carrie "all my right, title and interest in and to any real estate, with the buildings thereon, situated in West Tisbury, Massachusetts," Ex. 11, thereby consolidating title to the Luce Homestead in Carrie. Tr. I-43:13-18.

20. Ms. Szucs, the title examiner called to testify on behalf of William, Jr., testified that there was no monetary consideration for this deed, a conclusion that she reached based on the absence of excise stamps on the deed. Tr. I-46:9-12.

21. On April 7, 1955, Carrie deeded the Luce Homestead to William W. Thomas ("William, Sr.") and Meredyth C. Thomas ("Meredyth"), William, Jr.'s parents, as joint tenants and not as tenants by the entirety. Ex. 15; Tr. I-53:14-16.

22. William, Sr. died on August 6, 1956, Ex. 16, consolidating title to the Luce Homestead in Meredyth.

23. Meredyth conveyed the Luce Homestead, along with other property, to William, Jr., Nancy T. Bailey and Virginia Pond by deed dated September 20, 1983. Ex. 25.

24. By deed dated May 1, 2000, William, Jr., Frank Bailey and Virginia Pond, and by confirmatory deed dated October 12, 2001, Frank Bailey, as attorney-in-fact, conveyed the Luce Homestead to the Trustee of the Carrie Mae House Real Estate Trust. Exs. 28 and 29.

Title To The Subject Property

25. Record title to the Subject Property starts in this proceeding with a deed dated April 5, 1882 from Timothy B. Lovell ("Timothy") to Henry H. Lovell ("Henry") as follows:

A certain tract of wood, situated at a place called Middletown, in said town of West Tisbury, and bounded as follows: Beginning at a heap of stones by a walnut tree standing at a bend in the wall, by land of the heirs of Abijah Athearn; thence easterly to a stake and stones near the middle of the lot; thence more northerly to a rough oak tree standing on the north side of a pair of bars near the dwelling house formerly owned by William Rogers; thence southeasterly by the wall and by the land formerly by said Rogers to a corner of the land of the heirs of the late Alfred Look; thence by land now or formerly of Thomas N. Hillman and William Chase Jr. till it comes to land of the heirs of said Abijah Athearn; thence by land of said last named heirs to the first mentioned bound. Containing about eight (8) acres. Ex. 6; Tr. I-33:15-25; I-34:1-9.

26. Henry died testate on or about June 1, 1909. Ex. 8.

27. Henry's will left one-half of his estate to his sister, Mary, one-quarter of his estate to his brother, Samuel E. Lovell ("Samuel"), and one-quarter of his estate to his nephew, Edward, and to his niece, Carrie, the children of Mary. Ex. 8; Tr. I-37:16-25; I-38:1-6.

28. By deed dated February 16, 1910, Edward conveyed to his mother, Mary, "all my right, title and interest in and to any and all real property situated within the County of Dukes County and Commonwealth of Massachusetts of which Henry H. Lovell, late of West Tisbury, deceased, died, seized, possessed or entitled to." Ex. 9.

29. On April 14, 1913, Samuel died intestate, leaving his sister, Mary, as his only heir at law, as a result of which Mary held a 7/8 interest in the Subject Property and her daughter, Carrie, held a 1/8 interest. Ex. 10.

30. By deed dated December 7, 1944 ("the 1944 Deed"), Mary conveyed the Subject Property, along with two other described parcels, to Ernest S. Ex. 15.

31. The First Parcel in the 1944 Deed is of a parcel of land in Middletown, West Tisbury, title to which is derived from a deed to Henry in 1901. Ex. 15.

32. The Third Parcel in the 1944 Deed consists of two parcels of land in the northerly part of West Tisbury, title to which is derived from a deed to Timothy dated October 24, 1885. Ex. 15.

Evidence Regarding The Medeiroses' Chain Of Title - Lot 14 Of The Subject Property

33. By deed dated June 13, 1964, Ernest S. and Evelyn deeded Lot 14 to Ernest A. and his then-wife, Ms. St. Pierre. Ex. 17.

34. Ernest A. and Ms. St. Pierre began building a house on Lot 14 with funds provided through a mortgage with a local bank. Tr. III-76:19-25; III-77:1-17.

35. After the lot had been cleared and a foundation dug, the bank informed Ernest A. and Ms. St. Pierre that there was a problem with their deed, as a result of which construction work stopped. Tr. III-62:1-2.

36. According to Ms. St. Pierre, Ernest A. called Carrie, who then lived in an apartment in Vineyard Haven, and then he and Ms. St. Pierre went to Carrie's apartment. Tr. III-62:8-15.

37. Again according to Ms. St. Pierre, she and her husband gave Carrie a copy of a deed from Carrie to them of Lot 14, which had been prepared by the bank, and told her that they were trying to build a house on Lot 14. Tr. III-64:1-3.

38. Carrie told Ernest A. and Ms. St. Pierre that she had never owned the woodlands, that the woodlands were separate from the Lambert's Cove Road property, i.e. the Luce Homestead, that the Lambert's Cove property and the woodlands were two separate things, that the property sold to Ernest S. had nothing to do with the Lambert's Cove property, that there was a mistake and that she would take care of it. Tr. III-65:8-10; III- 65:20-24.

39. Ernest A., whose testimony during a June 19, 1987 deposition in Evelyn M. Moniz v. Meredyth C. Thomas, et al., Docket No. E1/26, Probate Court, Dukes County,

Commonwealth of Massachusetts ("the Probate Litigation") was admitted in evidence, described the interaction with Carrie as follows:

I had one conversation with her [Carrie] when I originally went to obtain a mortgage, a building mortgage on my house. They said there is some question of ownership of the land and I said, "What do you mean?" They said, "Carrie Luce has an interest in the land." I called her on the phone and she said, "I don't have any interest in the land, Mr. Medeiros. If you'd like I'll make things easier for you, I'll sign a release." Ex. 51 at 31-32.

40. Ernest A. further testified that this would have been in the 1964-1965 time period, that he did not pay Carrie anything for the release, that his only contact with Carrie was by telephone and that she "was agreeable and seemed very pleasant on the phone." Id. at 32.

41. By deed dated August 13, 1964, Carrie deeded Lot 14 to Ernest A. and Ms. St. Pierre. Ex. 18.

42. That deed is the document prepared by Ernest A.'s and Ms. St. Pierre's bank, and Leland Renier, who witnessed and notarized Carrie's signature on that deed, was the loan officer at the bank. Tr. III-67:11-18.

43. By deed dated August 4, 1975, Ernest A. and Ms. St. Pierre deeded Lot 14 to Ernest A. Ex. 22.

44. Lot 14 is now owned by Eric and Jeffrey. Ex. 35; Tr. III-168:11.

Evidence Regarding The Medeiroses' Chain Of Title - Lots 45 and 30

45. Ernest S. died on September 15, 1965. Ex. 19.

46. By deed dated September 29, 1965 ("the 1965 Deed"), Ernest A. and his sister, Frances G. Medeiros, deeded to their mother, Evelyn, their undivided interest in the three parcels deeded to Ernest S. by Mary in the 1944 Deed, less Lot 14, which had previously been deeded to Ernest A. and Ms. St. Pierre. Ex. 21.

47. By deed dated February 12, 1992, Evelyn deeded the three parcels conveyed to Ernest S. in the 1944 Deed, less Lot 14, to Eric. Ex. 26.

Evidence Regarding The Thomases' Chain Of Title To The Subject Property

48. On March 31, 1977, Evelyn filed the Probate Litigation in the Dukes County Probate Court. Ex. 45.

49. In that action, Evelyn alleged that she was the owner of the property described in the 1944 Deed, through the estate of her late husband and the 1965 Deed from her children. Id. at 1-2.

50. Meredyth, Samuel E. Lovell, the Estate of Prince Athearn, and Gabriella S. Webb, her estate, or their heirs, assigns, devisees or legal representatives, were named as respondents. Id. at 1.

51. With respect to the Subject Property, Evelyn's petition alleged that her title "is also clouded by the absence of the transfer of title back to Mary F. Luce, who by deed dated December 7, 1944 proposed to convey land to Ernest S. Medeiros which land she had previously conveyed to her daughter, Carrie M. Luce, and also by a deed from Carrie M. Luce to William W. Thomas (now deceased) and Meredyth C. Thomas in which the intention was to convey only two parcels in Lambert's Cove in West Tisbury, but not your petitioner's property, and therefore, your petitioner prays that Meredyth C. Thomas or any of her possible heirs, assigns, devisees or legal representatives be made respondents herein." Id. at 10.

52. Evelyn requested that her title to the property at issue in the Probate Litigation, including the Subject Property, be determined, established, confirmed and quieted in her and her heirs. Id. at 11-12.

53. Thereafter, by deed dated February 27, 1979, Meredyth conveyed to William, Jr., for no consideration, the same property that was the subject of the Probate Litigation, using the same descriptions as set forth in the 1944 Deed and the 1965 Deed. Ex. 24.

54. William, Jr. described this conveyance as a gift from his mother. Tr. II-4:20-22.

55. Meredyth and William, Jr., as her successor in interest, then filed an answer requesting that Evelyn's petition be dismissed and that William, Jr. be declared the owner of the property that was the subject of the Probate Litigation. Ex. 45.

56. Although William, Jr.'s memory with respect to dates was often not accurate, he testified generally that he started making efforts to have the Subject Property assessed to him (presumably this was after the 1979 deed was delivered to him by his mother, not in 1976, as he testified), and that he hired legal counsel in 1999 to address the issue of taxes with respect to Lots 45 and 30. Tr. I-153:23-25; I-154:1-15.

57. William, Jr. also testified that he knew that he and his wife had paid taxes on some or all of the Subject Property for a period of time, then stopped doing so, but also acknowledged that he was "easily confused" and had testified inconsistently at his deposition. Tr. II-10:7-22; II-11:4-7.

58. Eric testified that he has paid the real estate taxes on Lots 45 and 30 since 1992, when his grandmother deeded those lots to him, along with other property, and that no one else has paid them during that period. Tr. III-195:14-22.

59. In a letter dated December 2, 2011 from the Assessor to Eric and William, Jr. and his wife, Ex. 33, the Assessor stated:

The department has been contacted many times over the years by several parties regarding the ownership of Map 22 Lot 45 and Map 15 Lot 30. The files have recently come across my desk for review. This letter is being sent to clarify the Boards [sic] understanding of the situation and its position on the issues.

The Board understands that the Thomas's [sic] are claiming to own land that has been assessed to the Medeiros family for several decades. The Board has discussed the situation and determined that this is a title dispute between individuals. It is not the Towns [sic] responsibility to intervene in, or decide ownership of parcels in, this type of situation. That is best left to the parties involved in the dispute and the Land Court if need be. The department will continue to assess the parcels to Mr. Medeiros. If in the future the parties involved or the Land Court should determine that someone other than Mr. Medeiros is the rightful owner the board will update the property records. A copy of the information that has been provided to the Town is included with this letter. Please keep me apprised of any resolution to the situation. If you have any questions please do not hesitate to contact me.

60. On October 15, 2013, William, Jr. and his wife signed a voluntary bankruptcy petition pursuant to Chapter 13 of the Bankruptcy Code, which was filed with the United States Bankruptcy Court for the District of Maine ("the 2013 Bankruptcy Action"). Ex. 43.

61. On November 12, 2013, William, Jr. and his wife signed a document entitled Chapter 13 Plan Dated November 12, 2013 ("the 2013 Plan"). Id.

62. The 2013 Plan consists, in part, of a series of schedules, and the following declaration:

DECLARATION CONCERNING DEBTOR'S SCHEDULES

DECLARATION UNDER PENALTY OF PERJURY BY INDIVIDUAL DEBTOR

I declare under penalty of perjury that I have read the foregoing summary and schedules, consisting of 16 sheets, and that they are true and correct to the best of my knowledge, information, and belief.

Date November 12, 2013 Signature /s/ William W Thomas

William W Thomas Debtor

Date November 12, 2013 Signature /s/ Elise B Thomas

Elise B Thomas Joint Debtor

Penalty for making a false statement or concealing property: Fine of up to $500,000 or imprisonment for up to 5 years or both. 18 U.S.C. §§152 and 3571.

Id.

63. Schedule A to the 2013 Plan is entitled "Schedule A Real Property" and states in part:

Except as directed below, list all real property in which the debtor has any legal, equitable, or future interest, including all property owned as a cotenant, community property, or in which the debtor has a life estate. Include any property in which the debtor holds rights and powers exercisable for the debtor's own benefit.

Id.

64. Schedule A lists the following real property: House 33 Front St., Harrison, ME and raw land, 4.5 acres at 611 State Rd., Rogers Path, West Tisbury, MA 02575. Id.

65. The raw land listed in Schedule A is designated as Lot 29.1 by the Assessor, not the Subject Property. Tr. II-61:4-11.

66. Schedule A did not list the Subject Property. Ex. 43.

67. Schedule B to the 2013 Plan is entitled "Schedule B Personal Property" and lists, among other things, a one-third beneficial interest in the Carrie Mae House Real Estate Trust. Id.

68. The 2013 Plan provided that "[t]he debtor will also pay the trustee the following: $35,760 at the time of sale of property located on Martha's Vineyard." Id.

69. William, Jr.'s bankruptcy counsel filed an Amended Chapter 13 Plan ("the Amended Plan") on or about March 6, 2014, which provided that "[t]he debtor will also pay the trustee the following: $35,760 at the time of sale of the property located on Martha's Vineyard, to be contributed in month 36 or sooner," and that, if the debtors were unable to negotiate a loan modification with the lender regarding their principal residence in Maine, then the debtors "shall contribute additional funds to the plan from the [Martha's Vineyard] property sale sufficient to cure the arrearage on the Wells Fargo mortgage on the homestead." Id.

70. The Amended Plan did not disclose William, Jr.'s ownership interest in Lots 30 or 45. Id.

71. The bankruptcy court issued an order approving the Amended Plan on April 24, 2014, which order provided, among other things, that "[a]ll property of the estate, whether in the possession of the trustee or the debtors, remains property of the estate subject to the Court's jurisdiction notwithstanding 11 U.S.C. §1327(b)." Id.

72. In February 2015, William, Jr. and his wife sought authority from the bankruptcy court to employ a real estate broker to sell the Martha's Vineyard property, described as "Map 15, Parcel 29-1, Rogers Path, Off State Rd., West Tisbury, MA 02575." Id.

73. In March 2015, William, Jr. and his wife sought authority from the bankruptcy court to sell the Martha's Vineyard property. Id.

74. While listing their principal residence in Harrison, Maine and Lot 29.1, counsel for William, Jr. and his wife did not disclose the existence of other real property owned by them. Id.

75. The bankruptcy court issued an order on April 21, 2015, authorizing William, Jr. and his wife to sell Lot 29.1. Id.

76. On April 14, 2017, the trustee in the Bankruptcy Action filed a final report and account, stating that the Bankruptcy Action was filed on 10/15/2013, that the Plan was confirmed on 04/28/2014, that the Plan was modified on 12/5/2014, that the Bankruptcy Action was dismissed on 11/21/2016, that the Bankruptcy Action was pending for 41 months and that no unsecured claims were discharged without payment in full. Ex. 42.

Use Of The Subject Property By Ernest S. And His Successors

77. Evidence of use of the Subject Property by Ernest S. and his successors commences in the 1940s, when, according to Ernest A., Ernest S. constructed a pig pen on Lot 45 on which Ernest S. raised as few as two to four, or as many as seven or eight, pigs at any one time. Ex. 51 at 13-15.

78. According to Ernest A., the pigs were raised for the personal use of the Medeiros family during a period of rationing (presumably imposed during World War II) in order to be self-sufficient. Id.

79. A photograph of the pig pen when it was still in existence was marked as Ex. 54.

80. The remnants of the pig pen were still in evidence during this court's view of the Subject Property, are located directly across Rogers Path from the driveway onto Lot 43, Tr. III-176:9, and are shown in Exs. 48.90-97.

81. Ernest A. also testified generally as to Ernest S.'s commercial wood sales and, particularly, as to the sale of trees for spiles [Note 4] in the late 1940s. Ex. 51 at 18.

82. Regarding commercial wood sales, Ernest A. testified that they cut wood on the entire property, starting with standing dead wood. Id. at 17.

83. During the period from 1960 to 1965, when Ernest S. died, Ernest A. testified that they took large trees down to make room for other trees, id., and would sell approximately 10 to 12 cords each year, roughly one cord per acre. Id. at 18.

84. Ernest S. advertised his wood sales in the local paper once. Id. at 18-19.

85. Ernest S. and Ernest A. brush cut an area approximately three quarters of an acre in size as a place to store wood and "cord it up" during that time period. Id. at 19.

86. According to Ms. St. Pierre and Eric, this area was on Lot 45. Trs. III-69:8; IV- 54:3-8.

87. Ms. St. Pierre testified that Ernest S. stored wood and kept a truck parked on Lot 45 in the years before his death, and that he used a tractor on Lot 45 that he had purchased in the year before his death. Tr. III-69:8-24.

88. Kenneth Metell ("Mr. Metell"), Ernest A.'s cousin (Mr. Metell's father and Evelyn were brother and sister), testified that he visited the Medeiros family with his father every weekend as a child and that he helped with stacking wood, splitting wood and doing whatever Ernest S. needed to do with the wood from the time that Mr. Metell was in 8th grade until he was a senior in high school, from 1958 to 1964. Tr. III-127:8- 23.

89. According to Mr. Metell, Ernest S. would get wood from lots that had been cleared and stack it into cords to sell. Tr. III-127:24-25; III-128:15.

90. Eric identified the photograph marked as Ex. 48.27 as showing the clearing on Lot 45 that his father and grandfather made to collect firewood, and the photograph marked as Ex. 48.49 as showing the area where his grandfather stored firewood for sale. Tr. III-163:22-24; III-166:20-23.

91. According to Eric, this area was built up with bark and peat when he was a child, and there were a couple of saws located there. Tr. III-182:9-15.

92. Eric identified Ex. 53 as a photograph of one of the saw blades used to mill firewood, which he found when the peat had "rotted away." Tr. III-199:23-24.

93. Ernest A. testified that he continued to cut wood for personal use after his father died, to the extent of one to three cords of wood a winter. Ex. 51 at 18.

94. In the five-year period leading up to Ernest S.'s death in 1965, when his health started to fail, he did caretaking and gardening work. Id. at 22-23.

95. As part of that work, Ernest S. planted trees and wisteria on the Subject Property to sell to his customers. Id. at 22.

96. Ernest A. testified recalling as many as eight to ten trees or more planted by his father for sale. Id. at 23.

97. One pear tree and the wisteria were visible during the court's view and are shown in Exs. 48.99-48.101.

98. During this same period, while Ernest S.'s health was failing, Evelyn picked 14 or 15 quarts of blueberries on the Subject Property daily in season for sale to the local bakery. Ex. 51 at 23-24, 38.

99. In 1964, Ernest A. and Ms. St. Pierre started construction of their home on Lot 14, taking down trees, removing roots and digging a foundation. Tr. III-61:8-24.

100. According to Ms. St. Pierre, they moved into the house on Lot 14 in November, 1965, and she stayed there until 1970, when she moved to the adjacent farm house owned by her mother-in-law for two years. Tr. III-61:12-14.

101. When it was first constructed, access to the house on Lot 14 was by way of a driveway that came off of State Road between Lots 44.2 and 15, as shown in Ex. 38, to Lot 30 and then turning onto Lot 14. Tr. III-171:16-20.

102. Ex. 48.57 shows a pole on Lot 30, to the right of which is the area where the driveway formerly entered the Subject Property. Tr. III-170:20-25; III-171:1-5.

103. The mowed area on Lot 30 was used as a parking area and a turn around when the driveway was still in existence. Tr. III-171:24-25; III-172:1-3.

104. After the driveway was moved to the other side of Lot 14 off of Rogers Path, the area on Lot 30 that had previously served as a parking area and turn around was turned into a lawn. Tr. III-169:9-12.

105. Presently, there is no demarcation of the line between Lot 14 and Lot 30, and the lawn associated with Lot 14 exists on both sides of the line, as shown in Ex. 48.66.

106. Several witnesses testified to hunting on the Subject Property starting in the mid 1950s through 2018, Trs. II-94:22-25; II-95:1-2; II-95:19-21; III-114:22-23; III-115:8-10; III-129:16-21; III-153:21-23, to asking and receiving permission from Ernest S. or Ernest. A to hunt, Trs. II-95:6-9; III-32:2-4; III-116:2-3; III-129:18-21, and to being told where to hunt in order to stay on the Subject Property. Tr. III-32:25; III-33:1-2; III- 116:4-7; III-129:22-23.

107. Eric testified to excluding some people from and granting others permission to hunt on the Subject Property. Tr. III-192:22-25; III-193:1-2.

108. Eric has put up and taken down a tree stand, as shown in Ex. 48.29, used for hunting purposes, for more than 10 years on Lot 45. Tr. III-164:8-24.

109. Also, from 1976 until the mid 1980s, Eric and others used an area of Lot 45 as a shooting range. Tr. III-166:6-10; III-230:8-15.

110. Eric testified as to an old water tank, still on Lot 45 during the view and shown in Exs. 48.39-42, that was used by his grandfather, his father and by him as a target. Tr. III- 165:4-6.

111. Ernest A. posted "no trespassing" signs every 50 feet along the stone wall between the Subject Property and the adjacent property in or around 1978 or 1979 in order to keep out off-island deer hunters. Ex. 51 at 17.

112. In or about 2000, Jeffrey caused a load of gravel to be dumped so that it blocked an old roadway that traversed Lot 14 and Lot 30, in order to block people from accessing Lot 30 over it. Tr. IV-34:18-25.

113. What remains of that load of gravel was observed during the view and is shown in Ex. 48.52.

114. Eric also testified that he presently maintains Rogers Path from State Road to Lots 45 and 14, plowing snow, filling in potholes and pruning back vegetation. Tr. III-186:18- 20; III-187:1-3.

115. William, Jr. testified that from 1955 until 1971, from when he was approximately 9 to 25 years old, he stayed seasonally at the Luce Homestead. Tr. I-117:7-14.

116. He bicycled along Rogers Path during that period, as he preferred it to traveling over State Road. Tr. I-119:16-20.

117. William, Jr. testified that during that period of time, he did not observe fencing, enclosures, farming, pig pens, sawmills or "no trespassing" signs of the Subject Property. Tr. I-120:15-25; I-121:1-9.

118. William, Jr. was aware that Ernest A. had built a house on Lot 14. Tr. I-123:10- 12.

119. When William, Jr. married, in or about 1971, he and his wife moved to a house on State Road about one-half mile from the Subject Property. Tr. I-126:17-24.

120. From 1971 to 1979, William, Jr. went to the Subject Property five or six times a year, year-round. Tr. I-126:25; I-127:1-8.

121. He could clearly see Ernest A.'s house on Lot 14, knew that Ernest A. lived at that house, and that it was accessed off of State Road. Tr. I-127:13-15; I-128:12-18.

122. During this period, William, Jr. testified that he did not see any "no trespassing" signs, any fencing, or any enclosures. Tr. I-130:1-3.

123. During the period from 1979 to 1999, William, Jr. testified that he visited the Subject Property 10 to 15 times each year, Tr. I-133:7-9; that, while he was not sure where all the bounds were, he cut firewood on Lots 45, 29.1, 29.2 and maybe Lots 14 and 30, Tr. I-133:10-23; and that, while he saw wood and bushes on Lots 45 and 30, he did not see any fencing or enclosures, any farming or cultivation, any "no trespassing" signs, or a sawmill. Tr. I-134:10-22.

124. Also during this period, William, Jr., along with his wife, attended the 1987 deposition of Ernest A. taken in the Probate Litigation. Ex. 51 at 1.

125. In 1999, William, Jr. testified that he moved to Maine, but visited the island three to five times each year and was sure to inspect the Subject Property when he did so. Tr. I-136:13-21.

126. During the period from 1999 until 2011, when William, Jr. moved back to the island, he testified that he no longer cut wood on the Subject Property and that he did not observe fencing, enclosures, buildings, deer stands, cultivation, sawmills or "no trespassing" signs on Lots 45 or 30. Tr. I-136:22-25; I-137:1-23.

127. From 2011 until 2017, William, Jr. testified that he visited the Subject Property "frequently" and his observations were comparable to those he made during the period from 1999 to 2011. Tr. I-139:5-25; I-140:1-3.

128. In 2015, William, Jr. used a tractor to cut brush and small trees along the property lines of various lots, including the western line of Lot 29.1, the line between 29.1 and 29.2, and the northern boundary of Lot 45 to determine where various lot lines intersected with neighbors' properties. Tr. I-140:12-23; I-141:12-16; I-142:2-11.

129. In 2015 or 2016, both William, Jr. and Eric testified that William, Jr. asked Eric where various property lines were located. Trs. I-172:10-16; III-190:13-15; III-190:24- 25; III-191:1-3.

130. Eric testified that he showed William, Jr. the boundaries of the lots on which Eric was paying taxes: Lots 45 and 30. Tr. III-191:17-22.

131. According to Eric, William, Jr. did not claim ownership of Lots 45 or 30 in that conversation. Tr. III-191:25; III-192:1-2.

132. Lila DiBiaso testified that, in or about the summer of 2011, she and her husband built a tree house for their young children in a tree that they thought straddled the property line between their Lot 16, as shown on Assessor's Map 22, and the abutting Lot 30. Tr. II-69:2-5; II-69:13-20.

133. As seen during the view and shown in Exs. 48.77 and 48.78, the entire area covered by the tree house does not exceed 20' x 20.'

134. Ms. DiBiaso testified that she never approached the Medeiroses about constructing the tree house. Tr. II-71:7-9.

135. In 2017, a "no trespassing" sign reciting William, Jr.'s name was placed on the tree house. Tr. II-71:12-17.

136. Thereafter, the DiBiasos were contacted by William, Jr.'s lawyer to sign papers: a release and indemnity agreement and an agreement to remove the tree house at some later time. Tr. II-71:21-25; II-72:1-6.

DISCUSSION

The Statutory Claims

William, Jr.'s writ of entry pursuant to G.L. c. 237, §1 et seq., and William, Jr.'s claims and Eric's counterclaims to try title, G.L. c. 240, §§1-5, to quiet title, G.L. c. 240, §§5-10, and for declaratory relief, G.L. c. 231A, §1 et seq., all raise the issue of the parties' respective titles to and their possession, or not, of Lots 30 and 45. Each is addressed in turn.

William, Jr.'s writ of entry requires that he prove "that he is entitled to the estate set forth in the complaint and that he had a right of entry on the day when the action commenced," G.L. c. 237, §5, i.e. that he held title at the commencement of the action. Olson v. Carpenter, 296 Mass. 120 , 123 (1936) ("As a general rule a writ of entry deals only with the state of title at the commencement of the action") (citation omitted). Because the object of a writ of entry is to regain possession of real property, the "demandant" in such a case must not be in possession. Mead v. Cutler, 208 Mass. 391 , 392 (1911). Historically, this requirement led to "cases where a party in possession of real estate would be obliged to abandon his accustomed possession and use, in order to bring a writ of entry and try the right of an adverse claimant." Bevilacqua v. Rodriquez, 460 Mass. 762 , 769 (2011) quoting Munroe v. Ward, 86 Mass. 150 , 151 (1862).

Here, William, Jr. alleges that he is "the owner in fee simple with an estate in freehold" of the Subject Property and, to the extent that the defendants possess any portion of the Subject Property, he has been "wrongfully disseised." Amended Complaint ¶¶ 12, 46.

G.L. c. 240, §1, governs the parties' try title claims. That statute provides in pertinent part:

If the record title of land is clouded by an adverse claim, or by the possibility thereof, a person in possession of such land claiming an estate of freehold therein . . . may file a petition in the land court stating his interest, describing the land, the claims and the possible adverse claimants so far as known to him, and praying that such claimants may be summoned to show cause why they should not bring an action to try such claim.

According to the Bevilacqua court:

There are thus two steps to a try title action: the first, which requires the plaintiff to establish jurisdictional facts such that the adverse claimant might be "summoned to show cause why he should not bring an action to try his claim," and the second, which requires the adverse claimant either to disclaim the relevant interest in the property or to bring an action to assert the claim in question.

460 Mass. at 766. There are two jurisdictional facts "that must be shown to establish standing under G.L. c. 240, §1." Id. at 767. The plaintiff must be a "person in possession" and the plaintiff "must hold a 'record title' to the land in question." Id. Where those jurisdictional requirements are not met, this court "is without subject matter jurisdiction and the petition must be dismissed." Id. at 766.

G.L. c. 240, §6, governs the parties' quiet title claims. That statute provides in pertinent part:

If, in a civil action in the supreme judicial or the superior court, or in the land court, to quiet or establish the title to land situated in the commonwealth or to remove a cloud from the title thereto, it is sought to determine the claims or rights of persons unascertained, not in being, unknown or out of the commonwealth, or who cannot be actually served with process and made personally amenable to the judgment of the court, such persons may be made defendants and, if they are unascertained, not in being or unknown, may be described generally, as the heirs or legal representatives of AB, or such persons as shall become heirs, devisees or appointees of CD, a living person, or persons claiming under AB.

As with an action to try title, "[u]nder G. L. c. 240, §6, an action to quiet title cannot be sustained unless the moving party can show actual possession and legal title to the property." Deutsche Bank Trust Company Americas v. Dominguez, 2018 Mass. App. Unpub. LEXIS 409 at *4 (2018), quoting Bevilacqua, 460 Mass. at 767 n. 5. However, in contrast to a try title action, "[a]n action to quiet title is an in rem action, G.L. c. 240, § 10, brought under the court's equity jurisdiction." Bevilacqua, 460 Mass. at 767 n. 5. That "distinction is critical." Id. "[T]he plaintiff in a try title action may defeat the specified adverse claims through a default or by showing title that is merely superior to that of the respondent," while "a quiet title action requires the plaintiff 'not merely to demonstrate better title to the locus than the defendants possess, but requires the plaintiff to prove sufficient title to succeed in its action.'" Id. (citations omitted).

Accord Abate v. Fremont Investment & Loan, 470 Mass. 821 , 827 n. 14 (2015).

G.L. c. 231A, §1 et seq., governs the parties' requests for declaratory relief. That statute provides in pertinent part:

The supreme judicial court, the superior court, the land court and the probate courts, within their respective jurisdictions, may on appropriate proceedings make binding declarations of right, duty, status and other legal relations sought thereby, either before or after a breach or violation thereof has occurred in any case in which an actual controversy has arisen and is specifically set forth in the pleadings and whether any consequential judgment or relief is or could be claimed at law or in equity or not; and such proceeding shall not be open to objection on the ground that a merely declaratory judgment or decree is sought thereby and such declaration, when made, shall have the force and effect of a final judgment or decree and be reviewable as such; provided, that nothing contained herein shall be construed to authorize the change, extension or alteration of the law regulating the method of obtaining service on, or jurisdiction over, parties or affect their right to trial by jury.

In order to proceed under c. 231A, there must be an actual controversy and the plaintiff must have standing. Mass. Ass'n of Indep. Agents & Brokers, Inc. v. Comm'r of Ins., 373 Mass. 290 , 292 (1977) ("In order for a court to entertain a petition for declaratory relief, an 'actual controversy' sufficient to withstand a motion to dismiss must appear on the pleadings. G. L. c. 231A, §1. Even if there is an actual controversy, the particular plaintiff must demonstrate the requisite legal standing to secure its resolution. Hillman v. Second Bank-State St. Trust Co., 338 Mass. 15 , 19 (1958)."). "A plaintiff must have standing, a definite interest in the matters in contention in the sense that his rights will be significantly affected by a resolution of the contested point. See Massachusetts Ass'n of Indep. Ins. Agents & Brokers, Inc. v. Commissioner of Ins., 373 Mass. 290 , 292-293 (1977); School Comm. of Cambridge v. Superintendent of Schools of Cambridge, 320 Mass. 516 , 518 (1946)." Bonan v. Boston, 398 Mass. 315 , 320 (1986).

In Abate, the Supreme Judicial Court noted that "[a] try title action is one of several judicial avenues available to a property owner who seeks to challenge a claimed adverse property interest," citing to the declaratory judgment act and the quiet title statute referenced above. 470 Mass. at 826-827. Quoting from Bevilacqua, the court stated that the "'try title statute may now be something of an anachronism' when considered in light of modern statutes that allow a landowner to bring various actions to determine title." Id. at 827 n. 13. Here, whichever route is pursued, the result is the same for William, Jr.: he has failed to establish title to Lot 30 or Lot 45 and, for purposes of his try title and quiet title claims, he has failed to prove possession. [Note 5] And, because some or all of the title to Lots 30 and 45 is in Carrie's heirs, who are not parties to this proceeding and against whom no judgment can therefore issue, the court cannot adjudicate Eric's claims.

William, Jr.'s Lack Of Title

There are at least two substantial impediments to William, Jr.'s claim of title to Lots 30 and 45, one grounded in the law of mutual mistake and the other in the doctrine of judicial estoppel. Either ground, standing alone, is sufficient to defeat William, Jr.'s claim of title.

Mutual Mistake

"The phrase 'mutual mistake,' as used in equity, means a mistake common to all the parties to a written contract or instrument, and it usually relates to a mistake concerning the contents or legal effect of the contract or instrument." Ward v. Ward, 70 Mass. App. Ct. 366 , 369 n. 4 (2007), quoting Page v. Higgins, 150 Mass. 27 , 30-31 (1889). "The doctrine is employed when 'the language of a written instrument does not reflect the true intent of both parties.'" Polaroid Corp. v. Travelers Indem. Co., 414 Mass. 747 , 756 (1993). The mistake "must relate to an essential element of the agreement." Caron v. Horace Mann Ins. Co., 466 Mass. 218 , 222 (2013), quoting LaFleur v. C.C. Pierce Co., 398 Mass. 254 , 257-258 (1986). While the usual remedy for mutual mistake is reformation of the writing, Page, 150 Mass. at 30 ("The usual remedy, when, by accident or mutual mistake, a written contract does not express the actual contract of the parties, is by a reformation or rectification of the writing."), a court may also impose a constructive trust. Cavadi v. DeYeso, 458 Mass. 615 , 627 (2011) ("One type of constructive trust, implied by law as a result of mistake, violation of a fiduciary duty, or unjust enrichment, may be imposed, generally as between transferor and transferee, without proof of fraudulent intent."); Maffei v. Roman Catholic Archbishop, 449 Mass. 235 , 246 (2007) ("A constructive trust is a flexible tool of equity designed to prevent unjust enrichment resulting from . . . mistake, or 'other circumstances' in which a recipient's acquisition of legal title to property amounts to unjust enrichment.").

"The parol evidence rule does not bar extrinsic proof of intent" in cases of mistake. Polaroid, 414 Mass. at 756. Accord Van Ness v. Boinay, 214 Mass. 340 , 343 (1913) (parol evidence "well might be competent in an action to reform the deed, on the ground that it did not express the agreement intended by the parties."). That proof, though, must be "full, clear and decisive." Polaroid, 414 Mass. at 756.

In this case, it is undisputed that, just prior to the execution and delivery of the 1931 Deed, title to the Subject Property was held by Mary as to a 7/8 interest and by Carrie as to a 1/8 interest. Ex. 10. The issues raised by the evidence submitted at trial are (1) whether the parties to the 1931 Deed of the Luce Homestead, Mary and her daughter, Carrie, intended that the 1931 Deed would also include Mary's interest in the Subject Property; and (2) whether the parties to the 1955 Deed, Carrie and William, Jr.'s parents, intended that the 1955 Deed would include Carrie's interest in the Subject Property, whether that be a 1/8 interest if the Subject Property was not included in the 1931 Deed or a 100% interest if the Subject Property was so included.

The issue of what interest Carrie received from Mary in 1931 cannot be adjudicated in the absence of Carrie's heirs. [Note 6] As a result, this court cannot rule on whether Mary's 7/8 interest in the Subject Property passed by virtue of the language used in the 1931 Deed, despite the parties' arguments regarding the interpretation of that document. However, whether Carrie held a 1/8 interest or 100% of the fee in the Subject Property at the time of the 1955 Deed, the evidence at trial was full, clear and decisive that the parties to that instrument did not intend to include the Subject Property in the 1955 Deed. The most direct evidence of that fact was the trial testimony of Ms. St. Pierre and the deposition testimony of Ernest A. from 1987. While they may have differed on the details of their interaction with Carrie in 1964, both testified that Carrie told them that she had no interest in the Subject Property and that she willingly signed a release deed to them of whatever interest she might hold for no consideration. Ms. St. Pierre further testified that Carrie told them that she had never owned the woodlands of which the Subject Property was a part, that the woodlands were separate from the Luce Homestead, and that the property sold to Ernest S. by Carrie's mother had nothing to do with the Luce Homestead, that there was a mistake and that she would take care of it. She plainly did not understand that she had held title to the Subject Property or that she had conveyed it to William, Jr.'s parents in the 1955 Deed.

In addition, the evidence at trial established that William, Jr's parents did not understand that the woodlands, including the Subject Property, were included in the conveyance of the Luce Homestead in 1955. There was a complete dearth of evidence from 1955 until the late 1970s that William, Jr.'s parents engaged in any acts of any nature with respect to the Subject Property. The knowledge that the 1955 Deed could be read to include the Subject Property came some 20 years after the 1955 Deed, when Evelyn initiated the Probate Litigation on March 31, 1977, naming Meredyth as a defendant. Two years later, the first evidence that Meredyth claimed ownership of the same property (William, Sr. had died in 1956) appears in a deed from Meredyth to William, Jr., using the same descriptions as those used in the 1944 Deed from Mary to Ernest S. An answer was filed on Meredyth's and William, Jr.'s behalf in the Probate Litigation thereafter. William, Jr. also testified that it was not until the 1970s that he started his efforts to have the Subject Property assessed to him, and, on the record before this court, it does not appear that William, Jr. ever paid taxes on the Subject Property. [Note 7]

On these facts, it is clear that Carrie and William, Jr.'s parents did not intend that the 1955 Deed include the woodlands, including the Subject Property. To the extent that the 1955 Deed included a conveyance of the fee in the Subject Property, that conveyance was a mistake and would result in the unjust enrichment of William, Jr.'s parents and then William, Jr. [Note 8] Accordingly, this court rules that the Subject Property is held in a constructive trust for the benefit of Carrie's heirs, subject to a later determination in an action to which they have been made parties as to the extent of that interest and whether it has been lost through adverse possession to Eric.

Judicial Estoppel

"Judicial estoppel, or 'preclusion by inconsistent positions,' is an equitable doctrine which precludes a party from asserting a position in one legal proceeding which is contrary to a position that it has already asserted in another." Fay v. Federal Nat'l Mortgage Ass'n, 419 Mass. 782 , 787 (1995), quoting Patriot Cinemas, Inc. v. General Cinema Corp., 834 F.2d 208, 212 (1st Cir. 1987). "The purpose of the doctrine [of judicial estoppel] is to prevent the manipulation of the judicial process by litigants." Commonwealth v. DiBenedetto, 458 Mass. 657 , 671 (2011), quoting Canavan's Case, 432 Mass. 304 , 308 (2000). "[T]he doctrine is properly invoked whenever a 'party is seeking to use the judicial process in an inconsistent way that courts should not tolerate.'" Id. quoting East Cambridge Sav. Bank v. Wheeler, 422 Mass. 621 , 623 (1996).

In DiBenedetto, 458 Mass. at 671, quoting Otis v. Arbella Mut. Ins. Co., 443 Mass. 634 , 640 (2005), which in turn quotes and cites Alternative Sys. Concepts, Inc. v. Synopsys, Inc., 374 F.3d 23, 33 (1st Cir. 2004), the court stated that:

"two fundamental elements are widely recognized as comprising the core of a claim of judicial estoppel. First, the position being asserted in the litigation must be 'directly inconsistent,' meaning 'mutually exclusive' of, the position asserted in a prior proceeding[;] . . . [and] [s]econd, the party must have succeeded in convincing the court to accept its prior position."

The Otis court declined to adopt a third factor recognized by some other courts: whether the party asserting an inconsistent position would derive an unfair advantage or impose an unfair detriment on the opposing party if not estopped. 443 Mass. at 641. "Without the need to give separate consideration to whether a party has obtained an unfair benefit or imposed an unfair detriment on another party, judicial estoppel will normally be appropriate whenever 'a party had adopted one position, secured a favorable decision, and then taken a contradictory position in search of legal advantage.'" Id. quoting InterGen N.V. v. Grina, 344 F.3d 134, 144 (1st Cir.

2003).

In Otis, the Supreme Judicial Court quoted New Hampshire v. Maine, 532 U.S. 742, 750 (2001), for the proposition that "[a]pplication of the equitable principle of judicial estoppel to a particular case is a matter of discretion." 443 Mass. at 640. "Because of its equitable nature, the 'circumstances under which judicial estoppel may appropriately be invoked are probably not reducible to any general formulation of principle.'" Id. The Otis court did, however, recognize two circumstances where judicial estoppel might not apply: (1) "when a party's prior position was based on inadvertence or mistake," id. at 642, quoting New Hampshire v. Maine, supra at 753; and (2) where "the new, inconsistent position is the product of information neither known nor readily available to [the party] at the time the initial position was taken." Id. quoting Alternative Systems Concepts, Inc., supra at 35. Ultimately, the Otis court concluded that:

judges should use their discretion, and their weighing of the equities, and apply judicial estoppel where appropriate to serve its over-all purpose. That purpose is to "safeguard the integrity of the courts by preventing parties from improperly manipulating the machinery of the judicial system," and judicial estoppel may therefore be applied "when a litigant is 'playing fast and loose with the courts.'"

443 Mass. at 642, quoting Patriot Cinemas, Inc., supra at 212.

The United States Bankruptcy Court addressed issues similar to those in this case in Blanchette v. Blanchette (In re Blanchette), 582 B.R. 819 (D. MA 2018). There, Janis Blanchette ("Janis"), the mother of chapter 13 debtor Douglas Blanchette ("Douglas"), filed a lawsuit against Douglas in the Land Court in 2016 in which she sought recognition of a life estate in real property owned by Douglas in Middleboro, Massachusetts ("the Middleboro Property"), or the imposition of a constructive trust on that property. Id. at 820. In the Land Court proceeding, Janis contended that she and Douglas had entered into an agreement in May 2011 under the terms of which she would finance improvements to the Middleboro Property in exchange for what amounted to a life estate in an "in-law" apartment on the Middleboro Property. Id. at 820-821. While the Land Court case was pending, Douglas filed his petition under the bankruptcy code, resulting in a stay of the Land Court proceeding. Id. at 821. Janis timely filed a proof of claim in Douglas' bankruptcy action, claiming a loan to Douglas in the amount of $154,690.84, presently unsecured, but which she believed that the Land Court would ultimately determine was secured by the Middleboro Property. Id. Douglas filed an adversary proceeding objecting to his mother's proof of claim and seeking a declaration that she had no ownership interest in the Middleboro Property. Id.

Douglas filed a motion for judgment on the pleadings in the adversary proceeding, which the court converted to a summary judgment motion, in which Douglas argued that Janis was judicially estopped from asserting any interest in the Middleboro Property based on Janis' failure to list that interest in her own bankruptcy petition. Id. at 825. Janis had filed a petition for relief under chapter 13 of the Bankruptcy Code on August 9, 2012 and then filed an amended plan, which was confirmed by the bankruptcy court on May 31, 2013. Id. at 820. Janis did not list any interest in the Middleboro Property in her bankruptcy schedules. Id. On February 17, 2017, five years after its commencement, Janis moved for entry of discharge in her chapter 13 case, having completed all payments under her chapter 13 plan. Id. at 821.

In analyzing the judicial estoppel claim, the Blanchette court first found that the requirement of inconsistent positions was satisfied. Id. at 825. Contrary to her claim of an ownership interest in the Middleboro Property in Douglas' bankruptcy proceedings, "Janis' representation in [her own bankruptcy] schedules amount to a representation that she has no interest in, and no right to an interest in or possession of, the Middleboro property." Id. Regarding whether Janis had "succeeded" in persuading a court to accept her prior position, the Blanchette court had this to say:

In a bankruptcy case, where the original position consisted of a statement as to whether the debtor had or did not have particular assets at the time of the bankruptcy filing, that requirement is construed loosely and is satisfied if the court grants any relief in bankruptcy in reliance, in part, on the record created by the debtor's schedules. Here, it is uncontroverted that the Court did grant Janis relief: it confirmed her amended chapter 13 plan and then, upon her completion of plan payments, granted her a discharge. When the Court granted this relief, it did so in general reliance on the accuracy of the representations in Janis's schedules as to the extent of her assets. That is enough, even though - as for purposes of Douglas's motion for summary judgment I must assume - the plan proposed to and did pay all claims in their full allowed amounts.

Id. at 826 (emphasis added).

In this case, there can be no doubt that the position taken by William, Jr. - that he holds title to Lot 30 and Lot 45 - is inconsistent with the position taken by him in the 2013 Bankruptcy Action, where he failed to list those lots as assets on the schedule requiring that he list "all real property in which the debtor has any legal, equitable, or future interest." Based on the teaching of Blanchette, it also appears that William, Jr. succeeded in convincing the bankruptcy court to accept his prior position. He and his wife commenced the 2013 Bankruptcy Action to address arrearages in payments to the lender who financed their home in Maine, with the result that the lender was precluded from foreclosing on its mortgage. The 2013 Bankruptcy Action was pending for 41 months, the Plan was confirmed by the bankruptcy court on April 28, 2014, and William, Jr. and his wife made payments under the plan that resulted in their creditors being paid in full and the 2013 Bankruptcy Action being dismissed.

William, Jr.'s failure to disclose his interest in Lots 30 and 45 is also not the product of information not known at the time of the filing of the 2013 Bankruptcy Action. He was aware of and had been pursuing a claim of ownership of Lots 30 and 45 since the late 1970s, when his mother purported to deed him the Subject Property.

This court is left with William, Jr.'s testimony that his failure to list Lots 30 and 45 on his bankruptcy schedules was inadvertent and that no one was harmed as a result: William, Jr.'s and his wife's assets exceeded their liabilities even without consideration of Lots 30 and 45 and all creditors' allowed claims were paid in full. William, Jr.'s testimony regarding the inadvertent omission of Lots 30 and 45 does not ring true. William, Jr. testified to his efforts to lay claim to the Subject Property starting in the 1970s, including the hiring of two lawyers at different times and his attendance at Ernest A.'s deposition in the Probate Litigation. William, Jr. moved to Maine in 1999, but moved back to Martha's Vineyard in 2011, two years before filing the 2013 Bankruptcy Action. In late 2011, William, Jr. and his wife received the letter from West Tisbury's Assessor that is in evidence responding to William, Jr.'s claim of ownership of Lots 30 and 45. During the period between 2011 and 2017, William, Jr. testified that he visited the Subject Property frequently. Schedule A to the bankruptcy petition, signed by William, Jr. and his wife in 2013, could not be clearer as to the ramifications of a failure to fully disclose interests in real estate: a fine of up to $500,000, up to five years in prison, or both. And it is noteworthy that, on Schedule A, William, Jr. listed his ownership in the lot immediately abutting Lot 45 to the north, Lot 29.1. Based on that fact, it cannot be said that William, Jr. did not have his ownership of woodlots in West Tisbury in mind in completing Schedule A. In 2015, while the 2013 Bankruptcy Action was still pending, William, Jr. testified that he used a tractor to cut brush and small trees along various property lines, including the northern boundary of Lot 45. Both William, Jr. and Eric testified to a conversation in 2015 in which William, Jr. asked Eric where various property lines were located. Eric testified that he showed William, Jr. the property lines for Lots 30 and 45. Based on this evidence, the court does not credit William, Jr.'s testimony that the failure to include Lots 30 and 45 on Schedule A was inadvertent.

The court is left, ultimately, with the argument that no creditor was harmed by William, Jr.'s failure to disclose Lots 30 and 45 as assets in the 2013 Bankruptcy Action. Given the ramifications to the judicial system of false statements in court filings, that is too low a bar for this court to accept as the threshold for declining to judicially estop William, Jr. from taking a contrary position regarding Lots 30 and 45 now.

William, Jr.'s Lack Of Possession

As noted above, the plaintiff is required to prove possession in try title and quiet title actions. The Restatement of Torts (Am. Law Inst. 1934) and the Restatement (Second) of Torts (Am. Law Inst. 1965) both provide, at §157, the following definition of "possession:"

In the restatement of this Subject, a person who is in possession of land includes only one who

(a) is in occupancy of land with intent to control it, or

(b) has been but no longer is in occupancy of land with intent to control it, if, after he has ceased his occupancy without abandoning the land, no other person has obtained possession as stated in Clause (a), or

(c) has the right as against all other persons to immediate occupancy of land, if no other person is in possession as stated in Clauses (a) and (b).

This provision has been cited approvingly by the Supreme Judicial Court. See Cowden v. Cutting, 339 Mass. 164 , 171 (1959); New England Box Co. v. C & R. Constr. Co., 313 Mass. 696 , 709 (1943).

In New England Box Co., where the possession of lumber on land owned by the Commonwealth was in issue, the court reached back to 1836 for a description of the law related to possession of real estate:

In the early case of Cook v. Rider, 16 Pic. 186, 187-188, it was said, as to possession of land, that what acts amount to a sufficient occupation must depend upon the nature of the soil and the uses to which it is applied, and that enough must appear to show that the party claiming has entered upon the land and has indicated in some way the extent of his claim, and that the possession followed and was kept up "according to the nature and situation of the property."

313 Mass. at 710. More recently, in Cowden, supra, the court found that the plaintiff's "acts were sufficient to show possession in the owner of wild land which has not been occupied by another," 339 Mass. at 171, where the plaintiff recorded his three title deeds, [Note 9] put up "no trespassing" signs and removed a sign bearing the defendant's name, paid taxes on the property, informed the defendant of his ownership, and then brought an action of trespass against the defendant. It also bears noting, with respect to the possession required for a try title action, that [t]he petitioner must prove that he has the exclusive possession, as between himself and the respondent. If, as between them, the possession appears to be mixed or doubtful, the petitioner has not made out a case for compelling the respondent, rather than himself, to institute an action to try the title. Munroe v. Ward, 4 Allen 150 . Clouston v. Shearer, 99 Mass. 209 . Tompkins v. Wyman, 116 Mass. 558 . Proprietors of India Wharf v. Central Wharf, 117 Mass. 504 , 505 (1875)

Here, William, Jr. does have a recorded deed to the Subject Property, did assert control over a small portion of Lot 30 on which neighbors had constructed a tree house by placing a "no trespassing" sign on it in 2017 and then granting the neighbors permission to maintain the tree house with certain provisos, and did initiate this action to obtain clear title to and possession of the same. However, Eric, too, has a recorded deed to Lots 30 and 45 and has asserted counterclaims in this action claiming title to and possession of those lots. Eric has also paid the real estate taxes on Lots 30 and 45 since 1992 and is recognized by the Town of West Tisbury as the owner of Lots 30 and 45 for the purpose of assessing taxes. Leaving aside the compelling evidence of the possession of the Subject Property by the Medeiroses historically (including, among other things, the construction of a house on Lot 14 and the operation of a commercial lumbering operation on Lot 45), the evidence also established that Eric currently maintains Rogers Path from State Road to Lots 45 and 14, currently uses Lots 45 and 30 for hunting, has installed a tree stand on Lot 45 for deer hunting for the last ten years, and grants permission to some to hunt on that property and excludes others from doing so. In addition, in 2015 or 2016, Eric showed William, Jr. the boundaries of the lots on which he was paying taxes and of which he claimed ownership: Lots 30 and 45. [Note 10]

On these facts, William, Jr. has failed to establish that he is presently in occupancy of Lots 30 and 45 with intent to control that land, or that he has been but is no longer in occupancy of Lots 30 and 45 with intent to control it and that no other person has obtained possession. And he has plainly not established exclusive possession. In view of the court's decision regarding William, Jr.'s lack of title, he has also failed to establish that he has the right as against all

persons to immediate occupancy of the land. See Roman Catholic Archbishop of Boston v. Rogers, 2015 Mass. Super. LEXIS 65 at *17 ("Proof of title 'creates a prima facie case for the right to possession.' Nolan & Santorio, Tort Law, 37 Mass. Pract. Series § 4.1 (3d ed. 2005), citing Kostopolos v. Pezzetti, 207 Mass. 277 , 280, 93 N.E. 571 (1911)."). In short, William, Jr. has failed to establish possession of Lots 30 and 45.

Eric's Claims

Eric's claim to try title fails for the simple reason that he has failed to prove one of the jurisdictional prerequisites of the claim: that he holds record title to Lots 30 and 45. Bevilacqua, supra at 767 (plaintiff must establish as a jurisdictional fact that he or she "hold[s] a 'record title' to the land in question."). Depending on the interpretation of the 1931 Deed, he may hold a 7/8 interest in Lots 30 and 45 as a matter of record, or he may hold nothing. The resolution of that issue, and of Eric's claims for a declaratory judgment that he is the owner of Lots 30 and 45, to quiet title and for title by adverse possession, cannot occur in the absence of Carrie's heirs. See Uliasz v. Gillette, 357 Mass. 96 , 105 (1970) ("Even though the petitioners have no standing to question the respondent's title, it does not follow that we can declare in this proceeding that the respondent is the owner of the land. There is nothing in the record to indicate that we have before us all persons or parties entitled to be heard on that issue.").

CONCLUSION

For the foregoing reasons, judgment shall enter (1) dismissing Count II of the Amended Complaint and Count II of the Counterclaim for lack of subject matter jurisdiction, (2) dismissing Counts I, III, V and VI of the Amended Complaint with prejudice, (3) dismissing Counts II and IV of the Counterclaim without prejudice, and (4), on Count IV of the Amended Complaint and Count I of the Counterclaim, declaring that William, Jr. holds whatever interest he has in Lots 30 and 45 in constructive trust for Carrie's heirs and does not have record title or possession of Lots 30 or 45. The defendants' rights in the Subject Property vis-à-vis anyone other than William, Jr., including more particularly Carrie's heirs, are not adjudicated in this action.

WILLIAM W. THOMAS v. ERIC S. MEDEIROS, JEFFREY M. MEDEIROS, THE ESTATE OF ERNEST A. MEDEIROS, and THE RESOURCE, INC. FOR COMMUNITY AND ECONOMIC

WILLIAM W. THOMAS v. ERIC S. MEDEIROS, JEFFREY M. MEDEIROS, THE ESTATE OF ERNEST A. MEDEIROS, and THE RESOURCE, INC. FOR COMMUNITY AND ECONOMIC